The Perfect Heresy (16 page)

Read The Perfect Heresy Online

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

Others moved to the territories belonging to Raymond Roger, the count of Foix. His kinswomen, Esclarmonde and

Philippa, ran Perfect households, and his unofficial tolerance of the dissident creed was a secret to no one. He and Simon had signed, after much skirmishing, a year-long truce. The deal, brokered by Pedro of Aragon, was designed to give the Occitan cause some breathing room after the Trencavel debacle. In Toulouse, yet another destination for the Perfect, Count Raymond continued to show his customary reluctance toward persecuting his subjects.

Many of the Cathars in the old Trencavel lands chose to put their trust in the redoubts of the minor nobility. Hundreds of wandering dissidents heard of the hospitality of Geralda, the lady of Lavaur, a town midway between Albi and Toulouse. The Perfect hurried over the rolling farmland to find safety behind her walls. Although in theory a defenseless widow, Geralda had as a brother the pugnacious Aimery of Montreal. He made a tactical submission to Simon de Montfort in 1210, but everyone in Languedoc knew where his heart lay.

The other destinations for the displaced heretics stood dangerously close to Carcassonne and Béziers but seemed as reassuringly invulnerable as far-off Montségur. At Cabaret, Peter Roger and his people nursed the blinded of Bram. The Cathars were welcome in Cabaret, as were any knights ready to make risky guerrilla sorties into the valley. Some thirty miles to the east, an equally formidable hideout rose on the upland known as the Minervois. The capital of this hardscrabble region, Minerve, became a Cathar citadel. The local lord, William of Minerve, was a professed believer in dualism, and the fugitive Perfect deemed that his town, if attacked, would provide them a secure sanctuary from the fury of the crusade.

Geology appeared to bear them out. Even today clifftop Minerve wavers in the heat as if held aloft by faith alone, its

stone mansions clustered over a precipitous drop. On all sides save one are yawning canyons carved out of the bedrock by converging streams. Almost entirely surrounded by cliffs, the town seems to hover in space. Its sole level approach was blocked, at the time of the crusade, by a castle turning its massive windowless back on an arid plateau.

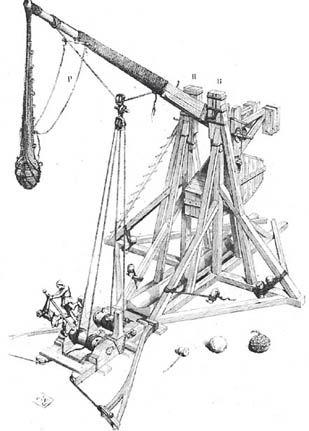

On June 15, 1210, the forces of Simon de Montfort appeared on the clifftops opposite Minerve, the rampant red lion on his personal pennant planted with finality on the heights. On Simon’s order the forces of the crusade separated, so as to triangulate better on the defenses of the town. Three catapults were set up, and soon a steady barrage of missiles went whistling straight across the abyss and into the town. Gradually, as the hours and days passed, gaping holes were smashed in the town walls. The crusaders, stuck out in the open on an inhospitable plateau, needed a quick victory before the summer grew hotter.

The crusading camp looked and sounded like a booming shantytown, the men scavenging for wood and hammering together makeshift huts and lean-tos in order to create some precious shade. But the carpentry had not all gone into shelter; after a few days a huge trebuchet, dubbed La Malvoisine (Bad Neighbor) by the crusaders, was rolled into position across from Minerve. Simon and his noble allies had dug deep in their purses to have this awesome Big Bertha of a catapult constructed. Some time in late June, Malvoisine’s outsized arm traced its first deadly trajectory toward Minerve. When the arm stopped with a shudder, an enormous boulder sailed in silence through the sunlight for a few instants before landing with a telluric thud—at a place somewhere on the cliff face below the town. Then another boulder hurtled to the same spot, and another. This was not impaired marksmanship; it was inspired artillery work.

A nineteenth-century rendering of a medieval trebuchet

(Roger-Viollet, Paris)

Malvoisine was pounding a walled staircase leading down from the town to the canyon floor, where another wall protected the city’s wells. Normally the fortified system was foolproof, affording protection from the keenest-eyed archer. But the sheltered stone stairway could not possibly withstand Malvoisine’s incessant bombardment. When access to the well went, so too would all hope of withstanding the siege. Within days, the decision was taken in Minerve: The trebuchet had to be destroyed.

One night at the end of June, a few men of the town slipped stealthily across the canyon floor. The saboteurs carried oily rags, ropes, knives, and some glowing embers. In silence they climbed the opposite cliff face in the blackness, inching their way

up to the silhouette of the catapult etched against the stars. Two sentries at the foot of Malvoisine were taken by surprise and slain. The men of Minerve then turned to their tall wooden tormentor, tied rags to it, splashed its legs with oil. The first, timid flame spiraled upward.

Another sentry, who had just come out of the bushes after relieving himself, shouted loudly until a knife was promptly buried in his heart. The alarm had been given, however, and the flames had just begun. The chronicler Peter of Vaux de Cernay did not say whether the saboteurs had time to clamber back down the cliff face to safety or were killed by the crusaders rushing to put out the blaze. Simon’s men beat the flames with coats, shirts, and bedding until Malvoisine was saved.

Slightly charred, the trebuchet resumed its work at daybreak. The staircase was promptly rendered unusable. Now, in concert with the three lesser catapults, Malvoisine started lobbing its enormous payload into the center of Minerve. Walls collapsed, killing those huddled behind them. The now waterless town, built on a layer of impenetrable granite, could not afford to let the rotting remains of the unlucky imperil the health of the living. Each night, the day’s dead were dumped into the canyon far below. The month of July wore on; the pitiless bombardment continued. Every evening brought with it the same ghastly chore; every morning, a parched despair. Like Carcasssonne, the town would be bested by thirst. William of Minerve knew at last that he had to surrender.

After much haggling, William offered all his lands and castles to Simon de Montfort. The northerner, impressed by his opponent’s candor in defeat, magnanimously gave William a minor valley fief in exchange for Minerve and the country that surrounded it. To William’s relief, Simon also agreed to spare

the town’s defiant inhabitants. A weird zephyr of mercy briefly danced through the canyon.

The agreement, worthy of thirteenth-century gentlemen, was about to be concluded when Arnold Amaury asked to speak. By chance, he had arrived at Minerve on the eve of William’s submission, just in time to influence the terms of capitulation. Simon had been made a great viscount through Arnold’s agency, so he could not overrule the legate’s wishes. And they seemed, on the surface, to be entirely reasonable. Everyone found in the town had to swear allegiance to the Church and abjure any other belief. Some of the more zealous northern pilgrims complained that these conditions displayed far too much leniency. They had come to Languedoc to wipe out heretics, but Arnold and Simon were giving these cat-buggering vermin a chance to lie their way out of danger. A chronicler had Arnold respond knowingly, “Don’t worry. I fancy that very few of them will be converted.”

William of Minerve returned to his people. Although credentes like himself would gladly swear the oath, the Perfect were immune from such base instincts as self-preservation. True, they had come to Minerve to avoid certain death, but only as a means of continuing their work as exemplars of otherworldly purity. Deliberate suicide, when other options were available, was a form of material vanity. But now they were faced with a choice between dying and renouncing the consolamentum, which was really no choice at all.

There were approximately 140 Perfect in Minerve, separated into two houses for men and women. None of the bearded, black-robed male Perfect agreed to take the oath. A priest was rebuffed by a Cathar who said, “Neither death nor life can tear us from the faith to which we are joined.” Three of the women, however, abjured the dualist faith and thereby chose to live. To

their Perfect sisters, these three were to be mourned, for they had relinquished their chance to commune with the Good for all time.

The 140 Cathar Perfect of Minerve were led down the ruined staircase to the canyon floor and tied to stakes planted in great piles of wood and kindling. The fire was lit. Peter of Vaux de Cernay, a chronicler and crusader fierce in his hatred of the heresy, claimed that the Cathars jumped joyfully into the flames, so perverse and life denying was their faith. The other chronicles omitted this detail. William of Tudela added only that “afterwards their bodies were thrown out and mud shovelled over them so that no stench from these foul things should annoy our foreign forces.” The first mass execution by fire of the Albigensian Crusade had taken place.

It was July 22, 1210, once again the Feast of St. Mary Magdalene.

The Conflict Widens

T

HE TRIUMPHS OF

S

IMON DE

M

ONTFORT

coincided with a diplomatic offensive by Raymond of Toulouse. Ever since August 1209, when he presented his twelve-year-old son to Simon and the great barons of France in Carcassonne, the fortunes of Raymond had waned. It took no great strategist to see that the crusade, once done with the Trencavel territory, might vent its violent piety on the rest of Languedoc. Despite Raymond’s elaborate penance in June and his passive presence in the camp of the crusaders at Béziers and Carcassonne in July and August of 1209, signs of ecclesiastical hostility toward him were not long in returning.

In September, he was excommunicated again. The charge—not having lived up to the promises he had made at his public humiliation at St. Gilles—was partially true but verged on the vindictive, given the short amount of time that had elapsed between promise and nonfulfillment. Arnold Amaury raised the

stakes by excommunicating the civic government of Toulouse as well and placing the city under interdict—that is, in a state of spiritual limbo during which no Catholic services, not even baptism and burial of the dead, could be legitimately performed. The accusation dealt with sheltering heretics, which the Toulousains disingenuously denied.

In attacking such a powerful force as the consuls of a rich and independent city, the papal legate was showing that the Church in Languedoc had been emboldened by the military success of the crusade. The count and his consuls, alarmed at this turn of events, decided to take their case directly to the pope. Fearing that he might be overruled, Arnold implored the excommunicates to stay in Languedoc and negotiate with him. His entreaties were ignored, and the Toulousains left for Rome in late 1209.

Innocent III must have awaited the aggrieved Occitans serenely. No pope in memory had been as powerful as Innocent was in the eleventh year of his pontificate. He ruled turbulent Rome with undisputed authority. He had consolidated his holdings, brought distant kingdoms to their knees, become the lawgiver of Europe, and purged the ranks of the clergy of undesirable loafers. His brother Riccardo had long ago finished constructing the Torre dei Conti, the brick fortress towering over the city as proof of the family’s might. It had taken Innocent and his kinsmen only a few years to coerce the great clans of the city into obedience; the Frangipani, Colonna, and others of their ilk had been bought or outmaneuvered and were forced to sit out his pontificate in tight-lipped silence. The so-called Patrimony of Peter, the swath of central Italy coveted by German emperors, was now firmly back in the camp of the papacy, its fertile estates and trading cities handing over a rich tribute to

Innocent every year. No one had paid much attention to the indigent popes of the twelfth century; now all of Europe sat up when Innocent rose to speak. Thundering anathemae had variously fallen on the monarchs of France, Germany, and Britain, and intractable disputes between laymen were regularly referred to the pope in his role as ultimate arbiter. A zealous bureaucracy dedicated to elaborating canon law had expanded, for Rome’s aim was nothing less than to codify, and thereby control, the affairs of a continent. Even the disgraceful Fourth Crusade had been turned to Innocent’s advantage. The sack of Constantinople led to the installation of a Latin patriarch in the episcopal palace of Byzantium. For the first time in centuries, all of Christendom genuflected toward Rome.