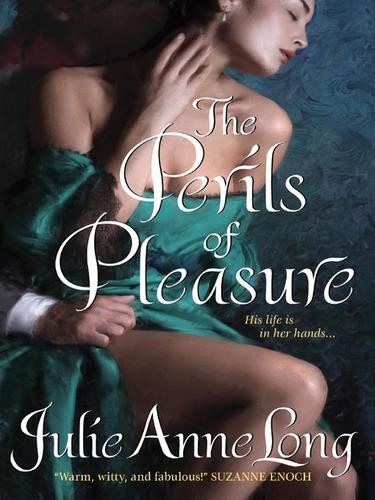

The Perils of Pleasure

Read The Perils of Pleasure Online

Authors: Julie Anne Long

Tags: #Fiction, #Romance, #Historical, #General

A

n

Avon

Romantic T

r

easure

nm

s was usual for a Saturday at the Pig & Thistle in Pennyroyal Green, the chessboard bristled with a miniature ivory and black battle, and Frances Cooke and Martin Culpepper hunched over it like two grizzled opposing generals in a place of honor in front of the fi re.

s was usual for a Saturday at the Pig & Thistle in Pennyroyal Green, the chessboard bristled with a miniature ivory and black battle, and Frances Cooke and Martin Culpepper hunched over it like two grizzled opposing generals in a place of honor in front of the fi re.

But these were the

only

usual things about Penny

royal Green today.

Ned Hawthorne paused in the endless task of keep

ing the floor swept to marvel: it wasn’t yet noon, but every one of the pub’s battered tables was crowded. Conspicuous among the regulars were Pennyroyal Green denizens who rarely appeared in the pub: the vicar, who could, irritatingly, be counted on not to drink a drop; the mysterious Miss Marietta Endicott of Miss Endicott’s Academy for Young Ladies had been coaxed down off the hill; a few of the Gypsies from the summer encampment on the outskirts of town had even wandered in, a violin dangling disconsolately from the hand of one of them.

Ned Hawthorne, whose family had owned the Pig & Thistle for centuries, had never seen so many somber faces.

And so little drinking.

For heaven’s sake, if they were going to have a proper wake for Colin Eversea, someone needed to get it started.

“’’twas only a matter of time before Colin Eversea was hung, you know,” he reflected into the silence.

Ah, this burst the dam. A great uproar of shouted agreement and dissent ensued.

“Oh, aye, if an Eversea were to ’ang at

long last

, ’e would ’ave been my choice,” was one snide opinion.

“Nay, Colin’s a good lad!” someone else disagreed vehemently. “The very best!”

“Good at being

bad

, Colin is,” another person shouted to general laughter and a few squeaked protests.

“Well, ’e has a good heart,” some diplomat inter

jected from near the hearth. “Kind as the day is long.”

“Owes me five pounds!” came an indignant voice from somewhere in the back. “I’ll nivver see it now.”

“Oh, you should ken better than to bet wi’

Colin Eversea

o’er anything.”

The voices trailed off. A lull ensued.

A throat was cleared.

“Then there was that bit with the countess,” came tentatively.

“And the actress.”

“And the widow.”

“And that horse race.”

“And the gambling.”

“And the

duels!

”

And voices once again tumbled all over each other, laughing and marveling, cursing and celebrating Colin Eversea.

Ah, that was better, Ned thought. Controversy made people thirsty.

Sure enough, the Pig & Thistle’s famous light and dark was soon flowing copiously from the taps fol

lowed by Ned’s favorite sound, the music of coins being slapped down on the bar and on the tables, and soon nearly everyone was sipping at something.

Without turning around, Ned thrust the broom he was holding off to one side, because even over the Colin Eversea inspired clamor, he’d heard his daughter Polly’s footsteps behind him. He would recognize them any

where, over any sound.

When she didn’t take the broom, he wagged it to get her attention, then glanced back and sighed at what he saw: purple rings beneath moist eyes, a long woebegone face, and bedraggled hair.

“Now, Polly . . . ”

“But I

loved

him, Papa.”

“No, you don’t, my dear,” he explained patiently. “He smiled at you but twice or so. That isn’t love.”

“That’s all it took, Papa,” she sniffed.

And

that

summed up Colin Eversea, the damned rascal.

There wasn’t a woman in the Pig & Thistle today between the ages of seventeen (that would be Polly) and seventy who wasn’t a bit misty, and more than a few were dabbing tears. The gents were looking right misty as well. As well they should. Colin Eversea was the most entertaining reprobate the Everseas had produced in decades, one of Ned’s best customers, and the gal

lows would deprive Pennyroyal Green of him in a mere few hours time.

Suddenly, a pleasant-faced gentleman in a many-caped coat, an innocent stranger who’d wandered in before the rest of the crowd and consented to try the dark ale, made a mistake.

He leaned across to Frances Cooke at the chess

board, and said:

“I beg your pardon sir . . . but am I to understand that

Colin Eversea—

the Satan of Sussex— hails from this town?”

Culpepper sighed extravagantly, slowly pushed his chair back from the chessboard, crossed his arms and gazed up at the beamed ceiling.

“New to Pennyroyal Green, are you, son?” Frances Cooke’s voice was mild, but he’d raised it just a little. A singular, strong voice, Frances Cooke had. Some might even call it a . . . portentous . . . voice. The vigorous debating in the pub tapered rapidly into a hush.

Everyone knew what was about to happen.

“Yes, sir,” the oblivious stranger told him brightly. “I was passing through on the way to Brighton when my horse threw a shoe. They’re taking care of me at the blacksmith. I’m Mr. William Jones.”

“’Tis pleased I am to meet you, Mr. Jones.” Frances Cooke thrust out his hand to be shaken by Mr. Jones.

Frances Cooke was tall and lean and bowed like a sapling confronting a strong wind. His hair was sparse, his gray brows so furry and alert they might have passed for pets, and spectacles gripped the tip of a nose reminiscent of the time Rome ruled Brittania. He knew things, Frances Cooke did: he knew the story behind the names etched into every tilting marker in Penny

royal Green’s graveyard; he knew where the stones used to build their church had been quarried and that the foundation of it had been built over a Druid temple; he knew the wood in the old table beneath his elbows came from Ashdown Forest.

Frances Cooke wasn’t bashful about

telling

what he knew, either.

“Ah, very good. Well, ’’tis an interesting story, the story of Colin Eversea. And to tell it properly, we need to go back to the time of the Conqueror.”

“Good heavens! As far back as that?” Mr. Jones was humoring Mr. Cooke.

Mr. Cooke gazed at him long enough to make Mr. Jones’s fingers twitch just a little nervously on his tan

kard of ale. “I wonder, Mr. Jones, if you happened to see a pair of oak trees growing very close together in the square as you rode into town?” he asked gently.

“I did at that. Two very grand trees. Pretty town you have here.”

Cooke nodded, as if this went without saying. “Mr. Jones, those oak trees were mere saplings when William the Conqueror set foot on English shores. And over the centuries their roots have grown so twisted together that they now battle each other for space and depend on each other to remain upright. And this . . . ”

Frances Cooke leaned forward a little, and every person in the pub reflexively leaned a little toward him, as if blown there by a breeze, and Frances Cooke’s voice took on the stentorian resonance of the practiced bard.

“

. . . this

, my friend, is a rather apt metaphor for the Everseas and Redmonds. For their families have anchored Pennyroyal Green since before this town had a name, since before the Conqueror set foot on these shores. And ancient grudges and secrets bind them fast, and curse them to this day.”

The stranger, despite himself, was enthralled into a short silence. “Good heavens!” he fi nally managed faintly. “Secrets and grudges? What

manner

of secrets and grudges?”

Everyone in the pub seemed quite pleased with the effect of the story on the visitor. Relative silence—there

was the sound of sipping, which pleased Ned Haw-thorne—and refl ection ensued.

“Well, they would not be

secrets

if we all knew them, would they, sir? But some say the bad feelings began when the first Saxon—a Redmond—cleaved the fi rst Norman’s—an Eversea—skull back in 1066 or so. The Redmonds, on the other hand, have it that it began even earlier, back before Rome ruled Brittania, back when all of our ancestors wore skins for clothes. They say an Eversea stole a Redmond cow.”

This surprised a short, nervous laugh from Mr. Jones. “Well, then. Was anything ever proved in the matter of the cow?”

“Nothing is

ever

proved when it comes to the Ever-seas,” someone groused from the back of the crowd, to a rustle of laughter.

Frances Cooke smiled tolerantly at the interruption.

“’Tis true, Mr. Jones. Both families are quite wealthy and grand now, but rumors are that the cow theft was only the beginning of the way the Everseas intended to build their fortune. They’re such a

cheerful

clan, you see, so ’’tis difficult to countenance. But piracy has been implied. Smuggling intimated. Much darker things al

leged. Kidnapping, larceny. Accusations have been lev

eled over the centuries, and accusations, as we all know, tend to originate somewhat in fact. But no one is certain where their considerable money originated, and no one has ever proved a thing. Which is why ’tis such a shock, you see, for

all

of us, to know that an Eversea will go to the gallows for murdering the cousin of a Redmond in a pub fight. Why now, after hundreds of years?”

Mr. Jones contemplated this. “Well, then. Do you think justice is being done with regards to Colin Eversea?”

Frances Cooke steepled his fingers beneath his chin and cast a glance toward the pub’s beamed ceiling. “It depends on how you define justice, I suppose, Mr. Jones. For ’tis said an Eversea and a Redmond are destined to break each other’s hearts once per generation. And Lyon Redmond, the eldest of the Redmond children, disappeared some years ago. The Redmonds believe ’tis because Olivia Eversea—she’d be the eldest daughter of the Eversea family—broke his heart.”

There was silence. The entire town knew the story, but it was rather a heady one for the stranger to absorb.

“But I think I can speak for all of us”—Cooke’s glance encompassed the room of villagers—“when I say I’m astounded that it has come to this hanging. And that the world will be diminished for want of Colin Eversea.”

There was a general sigh of concurrence, and one mutter: “ . . . owes me fi ve pounds!”

“To Colin Eversea!” Frances Cooke raised his tankard and voice high. “Reprobate, rascal, heartbreaker—”

“And friend,” Ned Hawthorne concluded fi rmly.

“And friend!” Mistiness and heartiness and irony blended in a roar of farewell.

All over the pub tankards were raised, clinked, and tipped down throats. Hands swiped foamy mouths, and Culpepper’s fingers pinched the top of Cooke’s queen and slowly, slowly levered it up.

Cooke might have been the town historian, but Cul

pepper usually won at chess.

nm

f all the myriad ways Colin Eversea

f all the myriad ways Colin Eversea

could

have met his demise—drowning in the Ouse at the age of six, for instance, or plummeting from the trellis leading up to Lady Malmsey’s bedroom window some twenty years later—somehow he’d failed to consider the possibility that he might hang. In fact, when all was said and done (admittedly, there was an awful lot to say and do), Colin had always thought he’d breathe his last breath lying next to the beautiful Louisa Porter of Pennyroyal Green after having been married to her for three or four decades.

Never, never did he imagine he might spend the last few hours of his life in a damp Newgate cell with a flatulent thief called Bad Jack.

And now Colin and Bad Jack sat in the pews of the Newgate chapel while the prison’s ordinary railed viv

idly about the tortures of eternal hellfire awaiting the two of them once their souls had been choked from their bodies. Next their shackles would be struck, their arms bound, and they would be strung up from the scaffold erected outside.

Bad Jack seemed bored as a schoolboy trapped inside

on a sunny day at school. He picked his fi ngernails. He belched, and thumped his sternum with his fi st to help the belch out. He even leaned back and yawned grandly, treating the ordinary to a view of his dark and mostly toothless maw. All in all, it was a bravura performance, but it was lost on the audience who had paid for the privilege of watching the condemned tortured by the pregallows sermon.

For it was Colin they had come to see.

They peered over the railings up above the chapel, eager to compare the actual man with images on the broadsheets rustling in their hands. Mere ink did not do justice to the reality of Colin Eversea, to his height, his loose-limbed grace and vivid eyes and strong ele

gant features, but myriad lurid images had abounded for weeks in the broadsheets. The English loved noth

ing more than a criminal with dash, and if he was gor

geous, so much the better.

Colin’s brother Ian had brought one of the most pop

ular broadsheets to him: on it he was depicted with Sa

tanic horns and a pointed tail and wielding a ridiculous knife—more a scimitar, really—dripping blood into a pool.

In a rare note of authenticity, the artist had seen fi t to sketch him in a Weston-cut coat.

“Looks just like you,” Ian had told him. Because that’s what brothers were for.

“What bloody nonsense.” Colin handed the broad

sheet back to Ian. “

My

horns are considerably more majestic.”

Ian began to smile, but it congealed halfway up. Colin knew why: “majestic horns” reminded both them of the first time Colin had pulled down a buck—in Lord Atwater’s Wood.

But neither of them said anything aloud. There were too many memories; every one of them, the smallest to largest, was painful as a stab now. Airing just one seemed to somehow give it more importance than the others. They never reminisced.

They exchanged inanities about broadsheets instead.

Colin handed the broadsheet back to his brother. “Will you have this framed? Something in gilt would suit.”

He’d said this more for the benefit of the warden, who hovered near him as often as possible to make note of his comments to sell to the broadsheets. Those broadsheets had become both cherished mementos and valuable investments. For Colin Eversea was not only a legend now—he was an industry.

There was even a popular flash ballad, sung in pubs, on street corners, on theater stages, and in amateur musicales:

Oh, if you thought ye’d never see

The death of Colin Eversea

Come along with me, lads, come along with me

For on a summer day he’ll swing

The pretty lad was mighty bad

So everybody sing!

Jaunty tune. Before things began to look so grim, back when their confidence had been unshakable, back when the Everseas’ petitions for Colin’s freedom were still crisp in the hands of the Home Secretary, his broth

ers had even written their own verses. Most of them concerning his sexual prowess, the size of his manhood or the lack thereof.

Because again, that’s what brothers were for.

It was all very ironic, Colin thought, given that he had spent much of his colorful life attempting to stand out from his forest of impressive brothers and earn his father’s admiration, even going so far as to join the army. But he’d managed to come home from the war entirely intact, whereas Chase, for instance, came home with a heroic limp, and Ian had been wounded. Then again, his father, Jacob Eversea, had

always

treated him with a sort of bemused detachment. No doubt because he was the youngest of the boys and had always been by far the biggest handful. Perhaps his father thought it wouldn’t pay to become too attached to him, because he’d known he was bound to do himself in inadvertently in a duel or a horse race or plummeting from the trellis of a married countess.

The ironic part was that Colin had at last managed to achieve what no Eversea in history had so far man

aged to do:

Get caught.

This made him the most legendary Eversea to date. The other irony

,

of course, was that he was entirely innocent of the crime. Then again, when the Charlies had found him with his hand on the knife protruding from the chest of Roland Tarbell, and when the sole eyewitness to the crime—Horace Peele, the man with the three-legged dog called Snap—had vanished into the ether, and when the only witness to the

witness’s

vanishing claimed fervently to have seen Horace Peele taken away in a fiery winged chariot . . .

Well, in all fairness, it was rather difficult to blame the jury.

The Everseas had found their petitions to the Home Secretary for Colin’s freedom mysteriously thwarted at every turn. Even negotiations for transportation in

stead of execution had been

oh

, so regretfully denied.

I’m innocent

was a constant scream in his head, and the sheer effort to keep from screaming it aloud—humor was his armor, and pride was his breeding—perversely forged those glittering witticisms the guards sold to the broadsheets. Colin found himself trapped in a fi ne, sticky net woven of long, dark history . . . and his own suspicions.

For now it was Marcus Eversea, Colin’s oldest brother, the one who had fished a sodden Colin out of the Ouse several decades ago, who would wake up next to Louisa Porter for the next four or fi ve decades.

It was Ian who mistakenly thought Colin would fi nd comfort in this news. After all, Marcus had come to Louisa’s financial rescue, and she’d of course gratefully accepted his proposal. Instead, the knowledge had bur

rowed thornlike into Colin’s mind, ensuring that he never slept a night through. Though to be fair, Newgate was hardly conducive to restful sleep anyway.

But Colin had rather a gift for noticing things, a gift honed in part as a result of being the youngest son in a crowd of siblings. And so he knew he was probably the only other person in the world who was aware that Marcus had loved Louisa since he was thirteen years old, and that Marcus, like himself, had fallen in love with her at a picnic at Pennyroyal Green.

Marcus would marry Louisa in a week’s time.

And in an hour Colin would hang.

The Eversea town house on St. James Square was so resoundingly silent that the birds performing a duet in the garden might as well have been Covent Garden sopranos. It was a cheerful and complicated song, with

runs and trills and pauses for grand tweets, and it echoed through the rooms.

Birds had no sense of occasion, Marcus Eversea thought.

Their father Jacob and their mother Isolde, siblings Ian and Chase and Olivia and Genevieve and Marcus— were perched on settees and chairs in the sitting room, motionless, already wearing mourning, in which they of course looked dashing. It suited the Eversea coloring, their dark hair and fair skin, the blue eyes that most of them had. A few, like Chase and Marcus, had dark ones. As for Colin . . . well, Marcus had always found Colin’s eyes difficult to describe. He was the exception, however.

Colin had ordered them not to go anywhere near the Old Bailey today.

“I won’t have it,” he’d said firmly. “Promise you’ll wait for me at St. James Square, speak of me if you can while you wait, and collect my body later. And mind you, I want the coffin with the brass fi ttings and a blue silk lining and a bloody good lock.”

Colin always knew what he wanted.

Louisa Porter was one of the things that Colin had wanted. And now, as she was soon to be an Eversea, she sat with them, together but slightly apart in a chair that enveloped her. Her hands lay very still in her lap, but she’d closed one tightly around the wrist of her other, as though she’d captured it and wrestled it into submis

sion, or needed to forcibly restrain it from . . .

From what? Marcus Eversea wondered. Rending her clothing? Tearing her hair? No, Louisa’s beauty and breeding were all she had to offer by way of dowry, so she could scarcely afford to indulge in dramatic gestures—unlike, for instance, the beautiful Miss

Violet Redmond, who excelled at them. Miss Red

mond once threatened to cast herself into a well over a disagreement with a suitor, and she had one foot hooked over the edge before the suitor dragged her back by both elbows. And then—wisely—the man had fl ed. Good Lord. Marcus realized he was very nearly afraid of Violet Redmond, and he was afraid of nothing. She’d cast her fine eyes in his direction once before. He knew he wasn’t the man who could possibly contain her, and he’d quickly looked away.

No histrionics for Louisa Porter. Instead, every

thing she felt right now was evident in that grip and her bloodless knuckles.

Marcus traced her profile with his eyes. He wondered if there would always be this . . . barbed catch in his breathing whenever he looked at her. It was sheer wonder that anything or anyone could be so very . . . so very . . .

With his usual pragmatism and sense of economy, Marcus abandoned the search for the right word, for he knew he would never fi nd it.

She turned toward him then and tipped her head up slowly, as though motion hurt her. Her eyes were a blue so absolute it made one want to invoke—oh, blue things, he supposed—and once again rue his vocabu

lary, comprised solely of land and horses and drainage ditches and investments.

He couldn’t help but think that Colin would have known precisely what sort of blue her eyes were. But Marcus knew that Louisa Porter hadn’t consented to wed him because of his ability to produce a metaphor. He absently fingered one of the mother-of-pearl but

tons on his Mercury Club waistcoat instead, for reas

surance. It was emblematic of the importance of what he could offer Louisa.

And it was Louisa who finally spoke into that awful silence.

“The birds are singing.” She said it very faintly, sounding surprised. As though she, too, found it an affront.

Isaiah Redmond squinted down onto the Old Bailey from his perch at the window. Without his spectacles, the throng was an undulating blur, calling to mind noth

ing so much as maggots feasting upon rotting meat. A smooth gesture later—all of Isaiah’s movements were graceful, studied, controlled, regardless of the urgency motivating them—his spectacles were out of his pocket and pushed up onto his nose, and the blur became the good people of London dressed in their Sunday best. Though scarcely less repellent for all of that.

Isaiah abhorred hangings. It was a sentiment he’d never before shared aloud, as it bordered on the radical. And if the Redmond family had spawned any radicals over the centuries, they’d been kept very good secrets indeed.

Then again, the Redmonds excelled at keeping se

crets. Every Redmond came into the world equipped with a sort of Pandora’s box, courtesy of being born a Redmond.

Isaiah, the current patriarch, had a veritable store

house of his own.

He intended to see this particular hanging through, however, as it represented a fissure in the pattern of his

tory itself. Today an Eversea would at last—

at last

—die on the gallows. Who knew what could happen next? Rivers might begin to flow uphill. King George might become a Quaker.