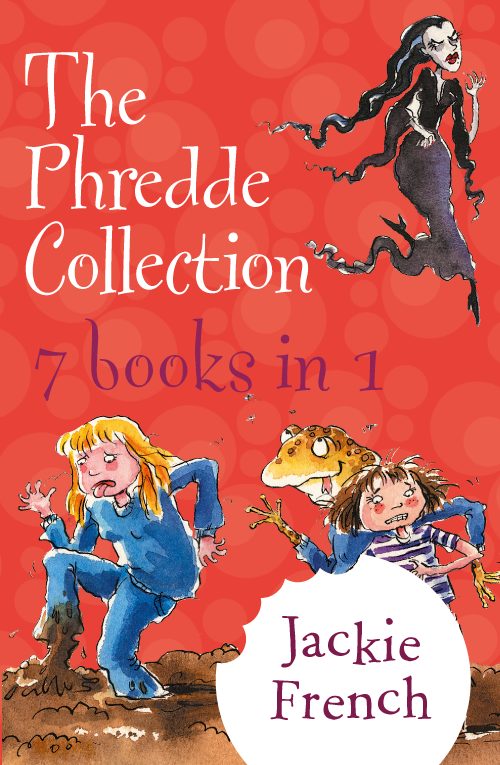

The Phredde Collection

7 books in one

A Phaery Named Phredde and Other Stories to Eat with a Banana

Phredde and a Frog Named Bruce and Other Stories to Eat with a Watermelon

Phredde and the Temple of Gloom

Phredde and the Leopard Skin Librarian

Phredde and the Vampire Footy Team

Phredde and the Ghostly Underpants: A Story to Eat with a Mango

Phredde and the Zombie Librarian and Other Stories to Eat with a Blood Plum

Jackie French

Jackie French

To Rory Bryan Quinn, with love

(and to Sarah Bennett with many thanks for all her suggestions!).

There are stories that move you, that become part of you, that make you think and dream…

Then there are the sorts of stories you read when school has stretched out like a long, flat road and you’re feeling totally brain dead and just want to read and laugh and eat a banana.

These are stories for those times.

Escape stories. Silly happy stories.

Stories to eat with a banana.

PS…Yes, I do mean eat.

Some people READ stories—mostly when they’re told they HAVE to go and read a story.

And some people EAT them—the way they eat potato chips or cherries…

or bananas.

‘Who are you staring at, bug eyes?’ snarled the fairy.

I dumped my schoolbag and glared at her. ‘I’m not staring.’

The fairy snorted from her perch on the front fence opposite the school. She was smaller than me…well, of course she was smaller.

She was a fairy.

She was about the size of my hand, with wings like melting iceblocks and a skirt cut out of rainbow wisps, and hair like shredded coconut and the tiniest, brightest purple joggers I’d ever seen.

I didn’t even know fairies wore joggers.

I didn’t know they had punk haircuts either, which just shows you how little I used to know about fairies.

And I don’t know if her voice sounded like a tinkling brook or not. I mean I’ve never even HEARD a tinkling brook.

The creek down the rec ground just goes PLOG when your soccer ball lands in it. If you heard it go ‘tinkle’ you’d think it had mutated with all the

shopping trolleys and hamburger wrappers people throw in it. (The creek doesn’t have a Ruritanian accent either.)

Her voice was ‘bell-like’ maybe. In fairy stories that’s what they say fairies sound like—if you can believe that stuff. But to be honest, the only bell I’ve ever heard is the one at school and she didn’t sound like that sort of bell at all.

‘If you stared any harder your eyes’d pop,’ said the fairy, fluttering her wings like a wasp in ‘attack-in-twenty-seconds’ mode.

Okay, so I was staring. It’s not often you see a fairy when you are on your way home from school, sitting there on someone’s front fence kicking at the roses with her joggers, the gold road to her castle shimmering through the air above her.

It was only a year since the civil war in Ruritania had spread Ruritanian refugees around the world—fairies and vampires, and all the rest. No one had ever heard of Ruritania much till then, except in fairy stories, but suddenly it was in all the headlines.

Not many Ruritanian refugees came to Australia—only a few hundred in all. But, with fairies and vampires being in the news so often, the publicity and sympathy allowed others with werewolf blood or gnome genes somewhere down the family tree to feel they could admit it. I mean, people you had never DREAMT were strange…

Like Mrs Olsen…

‘Finished yet?’ snarled the fairy.

‘Look. I’m sorry, okay? It’s just I’ve never seen a fairy before…’

‘That’s “phaery”, pinhead!’ declared the fairy.

I blinked. It sounded just the way I’d said it, except for a bit of a Ruritanian accent. The fairy made a rude noise.

‘P.H.A.E.R.Y.,’ she spelt out.

‘Well, phaery then, if that’s the way you want it.’

‘Oh, go bite your toenails,’ snorted the phaery, and disappeared.

Her castle flashed out of sight as well.

Mum was home.

She’s mostly stayed at home since losing her job, which is okay because Mum likes crosswords and doing practical things, not sitting behind a desk, except money’s tight.

For a moment, I couldn’t help comparing our place, with its thin walls, traffic muttering outside and our so-called garden—where NOTHING can grow because Mark’s size 14 feet crash down on it every time he loses his soccer ball (and you can’t even play soccer properly in our yard without the ball landing in next door’s daisies)—with the fairy’s, oops,

phaery’s

castle up among the clouds.

You wouldn’t hear the traffic up there. I bet there were dragons down in their dungeons, too. Great snarling dragons with flames and wings…

We can’t even afford a cross-eyed corgi.

Mum was trying to re-cover the sofa. The old sofa cover had ripped right across the seat last night when Mark thumped down on it. (Mark’s my older brother. He’s good at thumping).

Mum was using an old Indian-cotton bedspread to make the new cover and trying to follow the directions in a magazine. She had already done the

crossword in it—I suppose to give her enough confidence to tackle the sofa. (If you were to ask Mum what Heaven was like, she’d say it was a six-letter word that meant Paradise).

‘What do you think?’ she asked, giving the new cover a final twitch.

‘It’s okay.’

Actually, it had more wrinkles than the bulldog down the road. The poor thing looked like it was trying to wriggle off our sofa as fast as it could go. Not that I blamed it. Mark would only thump on it again.

Mum creaked to her feet. She says she’s got the Edwards’ knees. They always creak.

‘How was school?’ (If every kid in the world promised to scream next time they were asked that, maybe we could get adults to stop it. Do you KNOW how many times I’ve answered that question…well, yeah…I suppose you do…)

Anyway, I didn’t scream. Mum was having a hard enough time without my going operatic on her.

‘It was okay,’ I said instead.

‘Only okay?’

I shrugged. What could I say? That it’d been the lousiest day since the bead went up my nose at last year’s Christmas party?

That I’d been insulted by a punk phaery on the way home?

And that my new teacher…

I took a deep breath. Then I took another one. Mum was going to have to find out some time. Better now than Parent and Teacher night.

‘Mrs Olsen’s a vampire.’

‘She’s a what?’ Mum sat down, Plunk!, on the sofa and the new cover ripped right across the back and Mum said a word I’m not even supposed to KNOW, much less say.

‘What did you say?’ gasped Mum, as though it was me that had said something rude, not her.

‘Mrs Olsen’s a vampire. She admitted it today.’

‘A vampire!’ Mum reached for the phone. ‘Well I’m not having it! I don’t care what the anti-discrimination laws say, I’m not having a child of mine taught by some bloodsucker!’

‘Mum! Cool it,’ I said as calmly as I could. You have to be patient with parents when they start stressing out. ‘She doesn’t drink blood.’

‘But you said…’

‘I said she’s a vampire. But she doesn’t stick her fangs into anyone. Her teeth aren’t really all that big anyway. I mean, you’d hardly notice them if you weren’t looking.’

Mum looked at me suspiciously. ‘How does she survive then?’

‘She says her family has an arrangement with the abattoir for all the dried blood. She explained it this afternoon. We get the meat and they get the blood, and they mix it up whenever they need a snack…’

Mum put the receiver back reluctantly. ‘Well…I suppose that’s different.’

‘Yeah. Sort of.’

As a matter of fact, I thought it was totally gross. I’d nearly been sick when she talked about mixing thickshakes and things. Amelia down the back HAD been sick, or maybe that was the hot dog and tomato sauce and two red iceblocks she’d had for lunch.

But then I didn’t want Mum making a fuss and embarrassing me at school. You’ve got to be careful sometimes not to let your parents get wound up.

‘Mrs Olsen said her drinking blood is really no different from us eating meat.’

Mum blinked. ‘I never thought of it like that,’ she admitted.

‘Sure,’ I said reassuringly. More reassuringly than I really felt, to be honest. I mean, BLOOD—YUK!!! But then, I suppose if I was a cow I wouldn’t care if they turned me into hamburgers or vampire tucker. I’d still be just as dead.

‘Don’t vampires only come out at night?’ asked Mum.

‘Not exactly. Mrs Olsen explained that too. She said it’s been hard being a closet vampire all these years. She has to return to her coffin every hour during the day so she used to only teach night classes. But now that everything’s out in the open she can bring it to school and just pop inside for a few minutes between classes and…and she keeps it in the store cupboard with the art supplies…’ My voice trailed off.

It was actually pretty creepy having a coffin in the storeroom. The coffin was all dark wood and gold trim and once, when Mrs Olsen was getting out of it, I saw a flash of red satin inside, like something from a horror movie.

But I was getting used to it…

Mum was silent for a moment. ‘Do you like her?’ she asked finally.

I shrugged. ‘Yeah. Sort of. She’s an okay teacher. She’s not serious all the time like Mrs Haskins last year. Is there anything for afternoon tea?’

I almost went the other way home from school the next day, just to avoid the phaery. But I didn’t. I’d gone home from school that way ever since Mum dragged me off to my first day at kindergarten.

I wasn’t going to stop just for a phaery.

The fence was empty. No tiny purple joggers. No punk haircut.

No phaery.

For a moment I was almost disappointed. It would have been good to march past her, nose in the air.

‘Hey, human! Pay the toll!’

‘What?’ I blinked.

There were two kids standing in my way. They were taller than me, but not by much, and as skinny as chewing gum when you stretch it out too far.

I play soccer

and

basketball with Mark and, let me tell you, big brothers are great for your muscular development. But there were two of them and only one of me.

They looked sort of familiar. Yeah, I remembered them now—those two Year Eight’s who were always getting into trouble. Daniel something, and the other one’s name was Warren…

‘Pay the toll!’ yelled Warren, almost spitting in my ear. He wore some kind of green costume, too tight around the rear, and funny-looking horns (he’d made them out of alfoil) held onto his forehead with a rubber band. He looked like a mutant grasshopper.

I shoved my chin out. Mum says I look just like Great-aunt Selma when I do that. ‘What do you mean, pay the toll?’

‘We’re trolls and this is our bridge and you’ve got to pay the toll before you cross. Fifty cents. Each.’

I put my schoolbag down and folded my arms like Great-aunt Selma does.

‘In the first place,’ I declared, ‘this isn’t a bridge, it’s an ordinary footpath. In case you’ve never noticed, beetroot-brain, a bridge is a structure with something underneath. The only thing you’ll find under here is zecades of doggy doo. In the second place—you able to keep up with me here? In the second place, you’re not trolls. In the third place…if you hamburger maggots can count to three…’

‘We are so too trolls!’

‘You are not! You’re a pair of double-dumb school kids with horns tied onto an elastic band.’

‘So what?’ Daniel tried to look condescending. ‘Trolls’ horns are always held on by rubber bands! It’s our national costume, like…like clogs in the Netherlands. They wear wooden shoes and we trolls wear horns on rubber bands.’

‘But you’re not a troll! You can’t be a troll!’

‘Who says? I can be anything I want to be!’

‘But you’ve got to be born a troll!’

‘Well, who says I wasn’t?’

‘Oh, be quiet.’ Warren was sick of it. He shoved his shiny horns into my face. ‘If we say we’re trolls we

are.

And if we say you pay a toll, you pay the toll.’

‘Or what?’

‘Or this…’ Warren grabbed my schoolbag.

‘Hey, give that back!’ I reached for it, but Daniel held me back.

‘I’ll count to three,’ said Warren, gleefully, ‘and if you don’t pay the toll the bag goes under the first car that comes along. One…’

‘But I haven’t got fifty cents!’

‘Don’t believe you. Two…’

‘It’s true. Look, please—we just can’t afford another bag now. And all my books…’

‘Three…’ Warren lifted my bag. ‘And down it…aaaaaaahhhhhhhheeellppp!!’

I stared.

There was a troll climbing out of the drain down in the gutter. I mean a REAL troll.

This troll was small, and mean, and hairy. It smelt like it had been down that drain a long, long time. Its fangs were long and yellow and had never seen a toothbrush.

And its horns were definitely not held on by elastic bands.

The troll gazed up and down Warren as though Warren was the most delicious thing it had seen since Christmas dinner. It licked its lips. Then it stared at Daniel, as though it could just imagine him smothered in ice-cream and chocolate sauce.

And then it drooled. Green drool, drip drip drip on the footpath…

Daniel dropped my bag. One minute he was there, the next second he was gone. Warren stood there screaming. Suddenly the screaming stopped. Warren hiccupped twice, then he was running too.

Someone giggled behind me. I turned round just as the troll disappeared.

The phaery was back on the fence.

‘Don’t be scared,’ she said. ‘It wasn’t a real troll.’

‘I wasn’t scared.’

The phaery looked at me consideringly. ‘No, you weren’t were you? Why not?’

‘Dunno. I mean there wasn’t really anything to be scared of. It was too small to really hurt us. It just looked…different.’

‘The boys were scared.’ I knew what her voice sounded like now—the ‘ping’ when the tap drips into the bath. But it sounded better coming from her.

‘Yeah, well, they probably didn’t notice.’

‘Notice what?’

I grinned. ‘The troll was wearing purple joggers. I mean, those boys are dumb.’

The phaery flashed a grin back. She nodded. ‘Yeah, they are.’ Her accent sounded really nice once I got used to it.

We stared at each other for a moment. ‘My name’s The Phaery Ethereal,’ she offered. ‘That’s an eight-letter word meaning “of unearthly delicacy and refinement.” My mum’s into crosswords—and no funny jokes.’