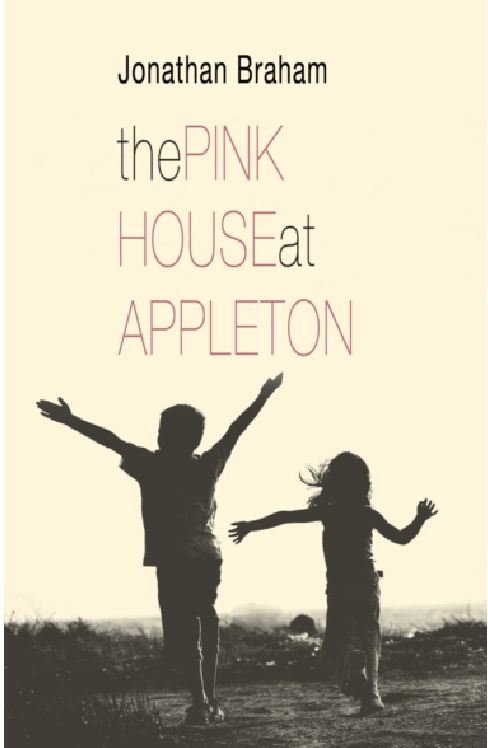

The Pink House at Appleton

Read The Pink House at Appleton Online

Authors: Jonathan Braham

Jonathan Braham

Copyright © 2015 Jonathan Braham

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study,

or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in

any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the

author, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with

the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries

concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

®

9 Priory Business Park

Kibworth Beauchamp

Leicester LE8 0RX, UK

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 978 1784627 492

A Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

Matador

®

is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

Converted to eBook by

EasyEPUB

For my sister,

Kimberley Ashbury Portland-Tobiaz,

who would have loved Yvonne.

Jonathan Braham was born John Lascelles Braham in Jamaica in 1948, the second of the six children of Harold Braham, industrial chemist, farmer and company director, and Victoria Braham (née Pratt) whose great great-grandmother was believed to have been a slave. Braham's paternal great great-grandfather was an English gentleman farmer and Jamaican estate owner.

Braham spent his formative years at Appleton Estate. He was educated at the Balaclava Academy, a Catholic prep school; Lewin's Prep, whose headmaster was the great Jamaican educator and historian, R.J.M. Lewin, the father of Dr Olive Lewin, concert pianist, author and social anthropologist. He also attended St Thomas More Prep, in May Pen, and later the private Anglican secondary school, Glenmuir.

In his last year at school he wrote his first novel, and short stories for the Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation radio programme, “Jamaica Woman”. Interviewed by the presenter, the popular actress, Leonie Forbes, he accepted the award “Man of the Week”.

At Mico University College where he was secretary of the students' council and a member of the Drama Society, he flirted briefly with the theatre, both as playwright and director, but continued to write for national newspapers and the Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation weekly radio magazine programme, “Rendezvous”. His poetry won awards in the annual Literary Festival and published in the Jamaica Journal.

In 1976, after marrying the English photographic model, Christine Barling, Braham left Jamaica for London with one purpose: to become a published novelist. But “life got in the way”. He studied Art History at the Open University, Television at London University, English literature at the University of North London and was, for over twenty years, chief education welfare officer and head of service in the London Borough of Brent.

The Pink House at Appleton

was published in 2011.

Some things you cannot forget, even those you think you've deleted permanently. The slightest impulse brings them back, every detail, every sound and smell, the deepest feelings in digitally enhanced, high definition reality.

Boyd Longfellow Brookes lived his special memory, planted in him over forty years ago, in Technicolor. A tragedy, it recurred even in dreams, in the dead of night, sometimes with such force that he lived the ordeal as a child, before it became memory.

That October afternoon it was the music that triggered it. He sat at his Apple Powerbook G4, trading stock on Schwab-Europe.com, tapping into the black keys, mouthing into the black telephone, sipping from a glass of red wine. He liked these pleasurable wine-satiated afternoons at home for they, peculiarly, heightened and sharpened his risk-taking.

Beyond the window, restive trees rustled, yellow leaves soared and fell away, and the first grains of rain landed on the windowpane. Out on the King's Road, Routemasters 11s and 22s passed like red shadows. The rousing wind, setting the trees in a rhythmic dance as the sky darkened, ruffled the feathers of the late pigeons as they dashed for home and Trafalgar Square. And suddenly the rain came down in white, belligerent streaks.

He quit the Apple Powerbook and ran to the balcony, enveloped in a sudden frisson of expectation. Stopping impatiently in the kitchen, he poured hastily from the half-empty bottle, a tasty Chateau Figeac, resting on the corian worktop. He supped the wine but did not reach the balcony. Music stopped him: the Saint-Saëns Violin Concerto No 3 in B minor, the

Andantino quasi allegretto

. Out from the little Bose radio on the bookshelf poured the haunting strains, heard over forty years ago in silence and distress. He stumbled onto the rain-swept balcony, the wine glass heavy in his hand.

He was eight years old again in the house at Appleton Estate, petrified. In that dark scene he stood alone in the drawing room, Mama weeping while Papa raised the strap and said, âBoyd, did you molest Susan?'

The world stopped. Mavis, lovely Mavis, smelling of garlic and escallion, rushed from the kitchen, protesting his innocence. âLawd, have mercy!' And when that wasn't enough, she accused them. âBut who could say such a thing, sar?'

Mrs Dowding could, that small-minded gossip, their next door neighbour, who thought the

Tropic of Cancer

was a

sex

book, a

bad

book. Evadne could, Ann Mitchison's maid. She saw any association between a boy and a girl as

lust of the flesh

.

The world turned against him the moment the alien word,

molest,

slid from Papa's lips. He did not know the true meaning of the word but saw it in their eyes, his family, gathered in the room around him, the one word,

guilty

. And something else too â the realisation that he, Boyd, was capable of such a monstrous thing, that all his living had been meaningless, untrue.

He could not tell Papa

what it meant to see Susan's eyes like pretty marbles, inhale the scent of her, see her pinkness and her gingham dress. It was impossible to tell Papa about his big feelings, his secret thoughts, the inner sanctum where the music came from, the part of him that had gone out to Susan. That was what Papa wanted to know, the very things he

himself could not talk about.

He had run from the room that day because he could not explain. And that night, distraught, alone in his room, he heard the heart-clutching music from the Mullard radio. And there was a certain comfort in hearing the music, lying in bed, knowing of the anger and indignation that prevailed, knowing that he had been utterly condemned, and knowing that he was totally innocent. But it was the events of that day that had quickened the end of Appleton because, after that day, the disaster was unstoppable. Papa, the great man, could not prevent it. He was involved in the destruction from the very beginning, as the facts later revealed.

In the final days, Papa never once returned home from the club till the grey of dawn. The Land Rover deposited him to the pink house, full of Appleton rum and a singular vision of the future for his family, his knee-length socks in heavy brown brogues, short khaki trousers crumpled, cotton shirt drunk with Royal Blend tobacco. He put the key in the lock, made a noise in the pantry to signal his arrival and continued down the hall in the dark to the bedroom where Mama lay, dried tears on cheeks, questions unanswered. And he mounted her in the dark under the covers, her flesh hot like the virgin sugar in his hands at the factory.

Papa thought not of Mama but of Miss Chatterjee at the club, whose smooth thighs rippled as she stroked the tennis balls. Miss Chatterjee, small of ankle, with the lipsticked mouth and a womanliness only travel, education and class could confer. It was Miss Chatterjee who Papa penetrated during the early months at Appleton, while Mama gave everything that she knew to give, and would have given more if asked. She was there to serve. But it was Miss Chatterjee who Papa saw and felt beneath him until the English family, the Mitchisons, arrived. Then it was Ann Mitchison with her quivering, seductive, kiss lips, all through the summer. Ann Mitchison changed everything.

At nights, unable to sleep, Boyd listened and heard the trembling music, whatever the hour that Papa arrived in the Prefect or the Land Rover, and Mama's submissive moans and cries as if she called out to him. Very often he was at their bedroom door in the dark, seeing their contortions, the moonlight splashing the sheets and silver-lining the dark furniture. And always there was Papa's vigorous back, bringing the music to an abrupt, discordant end, drumsticks and cymbals clattering down to the ground.

Standing and looking out from a rainy balcony in Chelsea, in October 2003, that was what he remembered. But that wasn't everything.

The Beginning

They lived in a pretty little house in the heart of the Black River valley, on a grassy slope overlooking Appleton Estate sugar factory in St Elizabeth parish. The house was painted in deep green and cream gloss, popular colours of the period and for houses of that sort. Papa said that it was a gingerbread house. Mama didn't think so and she should know; she was born in a gingerbread house, chalk-white with fanciful fretwork, deep in forty acres of gardens in St Catherine. Mama's mother, Grandma Rosetta, still lived there along with Mama's two brothers, Uncle Haughton and Uncle Albert.

When Mama left the gingerbread house as a young married woman, she moved to an estate house set in a field of pink bougainvillea at Worthy Park. Later, as Papa's prospects advanced, they moved to Appleton, driving a hundred miles in a single day in the grey Ford Prefect with the three children in the back, through the dusty roads of Clarendon, Manchester and St Elizabeth, to this house with front and back verandahs and balustrades. Papa was thirty-one and Mama twenty-nine years old. It was 1957.

In that year, Jamaica was still a British colony. Sir Hugh Foot, in starched white ceremonial uniform and exotic plumed hat, was governor of the island. Norman Manley, the Oxford-educated Jamaican lawyer, was Chief Minister and tireless advocate of “full internal self-government”. But independence was still five long years away. In those days, the sugar estates teemed with white English managers and other professionals and their families, living for the most part in pastoral civility with their black Jamaican counterparts.

âWe Brookes are first rate,' Papa boasted at the dinner table in their little Appleton Estate house. âDon't let anyone tell you otherwise. We are not one of those hurry-come-up families, and there are plenty of them about, especially in Kingston, with little education and no background. The name Brookes means something. And Pratt, too,' he added, making a concession to Mama's side of the family. Mama's family were landowners, small farmers. Papa's were plantation managers, professionals. He believed that the Brookeses had the edge in social ranking because they were sophisticated and skilled, not because, like the Pratts, they had had vast acres of agricultural land handed down to them.

Papa's smile was mischevious and as broad as his forehead, but there was hardness in his eyes.

âWhere's that boy?' he asked, looking about.

âGo and get Boyd,' Mama said quickly.

The little girl left the table instantly and they could hear her rushing feet on the polished wooden floor of the house heading in the direction of the drawing room.

âDidn't you hear the dinner bell?' the little girl asked the small boy curled up in the chintz armchair with a book at his face. âPerlita rang the bell five times.'

The boy didn't hear for he remained curled up, forehead furrowed, not moving.

âDidn't you hear the dinner bell?' his sister repeated impatiently. Then she said cunningly, â

Papa

wants you,' the stress on

Papa

.

The small boy reacted at once, took just enough time to fold the page at the correct place then leapt out of the armchair and hurried out of the room behind his sister. At the table their big brother sat upright, not amused. As they took their seats Papa paused and said, âHmm.'

âI didn't come to Appleton to fool about,' Papa continued, everyone at the table giving him their full attention. âEducation, ambition, hard work. That's what it's about. Some people only know how to waste time and not apply themselves. We Brookes will leave our mark here at Appleton.' He was an only child, the last of that line of Brookeses, without any property to his name and, although he would never admit it to anyone, he believed that he was a man alone against the world, but born to win. His three children, from the earliest days, heard the words of Longfellow from their father's lips at breakfast, lunch and dinner, and sometimes before bed:

The heights of great men reached and kept

were not attained by sudden flight,

but they, while their companions slept,

were toiling upward in the night.

The Appleton sunset painted a soft crimson upon the windows and against the white, freshly ironed cotton tablecloth. It added a dramatic edge to Papa's firm brown face. Through the French windows a valley breeze brought the tantalizing smell of boiling sugar, the exotic perfume of sugar estates, and quietly in the background the Mullard radio whispered

Love is a many-splendored thing

.

Mama, dressed in light maternity clothes, looked up. She had brothers and sisters aplenty and felt no passion, perhaps being a woman, about her family name, or about having to prove herself. She certainly didn't believe that there were any battles to be fought. But she wanted to leave her mark. She wanted to become somebody, an ordinary somebody, but somebody of her very own, not just a housewife and mother. But she said nothing. When Papa had the floor, impassioned and impatient, delivering his little lectures, it was best to listen, even if she had heard it all before.

âBrains, intelligence, class,' Papa reminded them, his big, even teeth bared in a self-congratulatory smile. âGawd! That's what we Brookeses are made of. I could run the whole shooting match down here.'

The move from Worthy Park Estate was a timely one. As deputy assistant chief chemist, Papa's chances of advancement at Appleton were good. His ultimate objective was to leave Appleton after a few successful years and take up a senior appointment, possibly as chief chemist or general manager, at another big sugar estate like New Yarmouth or Monymusk. But the move was good for another reason. It put a lot of distance between him and a certain matter, an indiscretion, which took place in an outlying district, Lluidas Vale, one reckless night almost eight years ago, after he'd been drinking a little too much. He was not proud of it and, in fact, had only known about the result of his misdemeanour shortly before he left for Appleton. He didn't think Mama knew about it â there was no way in which she could know. But women had a way of knowing.

âIt's nice here,' Mama said tentatively, now that the lecture was over. âDoctor, dentist, pharmacy, shops, a reliable train service, the nursing home at Maggotty, good hospitals in nearby Mandeville, and a design academy too.' Her eyelids fluttered like a bashful girl's. This bashfulness, this little-girl quality in her, was what appealed most to Papa when they first met. But now, after many years, he found it debilitating and was impatient with it. He wanted a little haughtiness from his wife. He wanted just a teeny- weeny bit of snobbery, a little malice, which should bring about the sophistication and the fascination he so wished she possessed. Mama was far too trustworthy, too innocent. He wanted stimulation, challenge, but all he got was fidelity, devotion.

âNice?' Papa said, thinking it a strange word to use to describe a place that would determine their future.

Mama paused, not quite knowing how to deal with Papa's reply. âWill the electricians come tomorrow?' she asked, changing the subject. âThere's no light in the pantry. And we could do with an outside light by the ironing room and the laundry room.'

âDixon will see to it,' Papa said brusquely. âDidn't I say so? He'll do it, or send one of his lackeys. They have nothing to do but stand about.'

âAnd the stove smokes. It makes poor Perlita cough and sneeze.'

âCough and sneeze? She should be so lucky. Can't she get, what's his name, Delroy, that brother of hers, to look at it? Lazy son of a gun. He's always idlying about with his long hands at his sides and that lazy look in his eyes. I don't understand these people. They can't do anything without being told? And what is he doing hanging around the property day after day for? If he wants to be a yard-boy he needs to get to work.'

âHe doesn't come here anymore. Perlita said he got a job with the Public Works Department, breaking stones on the road.'

âI'd like to break stones on his head, that lazy good-for-nothing,' Papa said. Then he sighed. âAll right, Victoria. I'll see to it. Probably hasn't been cleaned since the day they put it in. People don't seem to understand that the only way to maintain anything is to clean it. That kind of attitude can only hold back the country.'

âI could bring back the gloss with a little Vim and steel wool,' Mama said.

Papa's response was swift. âI didn't take you all the way from St Catherine to Appleton to clean house. That's maids' work.'

Mama, aghast, opened her mouth to speak but closed it as a sudden movement caught her eye. The curtains at the door parted and Perlita appeared, having been listening keenly to the conversation from her place in the kitchen. From habit she wiped her hands carelessly and lethargically on her apron. She was a St Elizabeth rural woman, not given to speaking with care and restraint.

âMr Brookes, sar,' she said with insane boldness, âwho going to deal with the travelling salesmen, sar? They come from off the road, through the gate and right up into the verandah, sar. Three, four of them a day, selling things Mrs Brookes don't need. And them don't take no for an answer. Them is hooligan, sar. Poor Mrs Brookes have to deal with them all the time, and she is expecting. The house too close to the road, sar, too close.'

Papa considered this interruption shocking impertinence and paused long enough to demonstrate it. âDon't you have work to do in the kitchen?' he asked, glowering.

âYes, sar, ma'am,' Perlita said, bowing slightly as she left.

Papa's expression was one that Mama knew well. Perlita was walking on thin ice.

âIt's your job to train her,' Papa hissed, leaving the table. âDo you expect me to do everything?'

Papa, who at first liked the new house, had quickly grown to dislike it. All he heard from the brief interlude with Mama and the hapless Perlita were house problems. The house did not say

Harold

Brookes

. It did not say

Home of the

Brookeses, a first rate family

. It said

ordinary

. Papa wanted a house in a pastoral setting, with a garage, gardens, an expanse of lawn and a long driveway. His house should reflect not only his status on the estate but the level of his intelligence, his

savoir-faire

. And, frankly, he did not expect to wait forever. He learned from his father, the great Lascelles Brookes, banana plantation manager, dead now, that

prosperity did not come to the meek, to those who stood in line.

* * *

Appleton was green and blue. Vast fields of sugar cane stretched into the distance, their green shoots steady in the wind on the valley floor. All day long the lemonade-sweet heat shimmered across the valley. Blue mountains crouched on the sunny horizon and green hills reached up from the open spaces, cut through by the snaking Black River. In the warm perfumed evenings the sunsets were radiant pink, painting the powdered faces of the estate wives sitting on the terrace at the club drinking Babycham and gossiping, while ignoring their restless husbands lined up at the bar. And at night a million stars, like golden sugar crystals, crowded the sky.

On the grassy slopes stood the big houses of the managers, smaller houses for staff on their way up the management ladder and houses for others just beginning the climb. Papa's house was in-between. It was solidly built, facing the road and the sprawling, silver, steaming factory: a giant engine down in the heart of the valley. In the mornings, as the sun crept up the hill, the verandah lay in soft shade. The three Brookes children liked to sit there and wave to the people who passed. The children.

A small, glossy, perforated black and white photograph of them in the family album showed the eldest child, Barrington Winston Brookes, looking grave and grown-up at eleven years old, the plumpest of the three, in pepperseed trousers and starched white shirt. He held the hand of his sister, Yvonne Elizabeth Brookes, the youngest at five years old, forehead round and intelligent, hair pulled back, polka-dotted dress well above dimpled knees, a mischievous smile about her lips. Boyd Longfellow Brookes, the smaller of the two boys, dressed in short linen trousers buttoned to a white shirt, stared into the camera, brows knitted, enquiring, troubled. He gripped his little sister's hand tightly. His feelings and his thoughts, mostly in grey and blueberry-blue, dwarfed him. He was eight years old.

Every morning at this new house at Appleton they looked at the people passing by: the estate postmen who arrived on rickety red bicycles, zigzagging across the road, shirt-tails flapping in the breeze. The Bible women, dressed in dusty black, who relentlessly tried to save souls, having the front door slammed in their faces by Papa or an enraged Perlita. Mrs Moore, the chief engineer's wife, with a pretty parasol, flowery dress, and a hat encrusted with artificial fruit, who waved and waved even when they thought she'd stopped waving. Miss Casserly, the young teacher with the sun on her face, cotton skirts like spread hibiscus, and always picked up by a punctual car long before she got to them. Mr Dixon, the electrician with gloved hands and tools sticking out of his pockets, who lived at the Bull Pen, the batchelors' residence, but was to be found on the hill daily, fixing fuses, plugs and switches, wrapping black tape over wires and joking extravagantly with the maids. Mr Tecumseh Burton, the tailor from Balaclava with the American accent (Perlita called it a âtwang') who, touting for business with his nephew, Edgar, drove up in a black Chevrolet with bales of cloth, took Barrington and Boyd's measurements and delivered well-cut short trousers a week later, saying to Papa, âAt a good price, suh'. Mr Jarrett, the sprayman, his magnificent brass spraying equipment heavy on his shoulders and his fragrant, gorgeous smell. He visited often to pump up his apparatus and spray the air. The children loved him the most, because he was tall and thin with sleepy eyes and praying-mantis features. They smelled him before they saw him. His aroma was of the lovely spray fumes and DDT. As he slowly passed, the sun glinting off him, they breathed deliciously, waving deliriously. He always turned to look with mock surprise as if seeing them for the first time, his cigarette never leaving his lips. Sometimes he presented them with sweets: Mint Balls, round and white with pink stripes down their sides and covered in white sugar, vivid pink and white coconut candy that crumbled in their hands, sticky Staggerback that clung joyfully to their teeth and Paradise Plums wrapped in crackling greaseproof paper. The Paradise Plums he took out one by one from a paper bag like a naughty but wonderful magic trick, each one pink on top and yellow underneath, as the children trembled with unsurpassed delight.