The Places in Between (19 page)

Read The Places in Between Online

Authors: Rory Stewart

Many of my hosts had been war leaders. Most of them had fought against the Russians but not all for the same groups. Haji Mohsin and the red-bearded Agha Ghori had been among the leading Jamiat commanders in the province, but the headman of the dog's village was a commander for the Pakistani-funded warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

A few, such as Gul Agha Karimi—who wrote my letters of introduction—had worked with the Russians. He and some others seemed to have been largely forgiven for collaborating. But the Russian chief of the KGB-KHAD who ordered the planes to bomb Haji Mohsin's village would be killed if he stepped into this area.

32

Things became even more complicated under the Taliban era because anti-Russians found themselves on opposite sides. Some men, such as Agha Ghori, genuinely retired. Haji Mohsin Khan had been pro-Taliban and was therefore allowed to run the valleys for five years during the Taliban period.

The defeat of the Taliban meant that everything changed again in less than two months. The anti-Taliban commander

33

had now taken back control of the area from Haji Mohsin and was policing Haji Mohsin's territory with his own men from Shahrak. This was why Wazir did not recognize the gunmen who passed us on the snowfields. Meanwhile, Haji Mohsin was refusing to hand over his Taliban deputy.

34

My host, Seyyed Umar, was the man of Haji Mohsin Khan, while the tall guest who had just left was the man of Haji Mohsin's enemy. But ten years earlier they had stood beside each other to shoot Najibullah's men by the river.

"Why did you become a Mujahid?" I asked Seyyed Umar.

"Because the Russian government stopped my women from wearing head scarves and confiscated my donkeys."

"And why did you fight the Taliban?"

"Because they forced my women to wear burqas, not head scarves, and stole my donkeys."

It seemed if the government did not interfere with his women's headdress and his donkeys he would not oppose it. But Seyyed Umar had not fought the Taliban. As Haji Mohsin Khan's man, he had been one of their representatives.

There were five of us in the guest room and for two hours we sat in silence. It was an overcast afternoon. Seyyed Umar sat by a large window, clicking his rosary. He shifted his head to look down at the black ridge, the mud below the river, and the tracks in the snow. Occasionally he sighed or cleared his throat. Outside a door creaked and a horse whinnied. Half an hour later, two ragged men and their donkeys came up the hill, and the children of the village threw snowballs at them. The men, exhausted at the end of their day's journey, smiled.

Seyyed Umar and the others could not work in the fields because of the snow; they had lived here together since they were children; nothing had happened recently that was worth talking about, and they were illiterate. Throughout the long afternoon they waited in silence for the call to prayer, dinner, and bed.

A hundred years ago this valley had been uninhabited. Seyyed Umar's great-grandfather was a mullah who came here from the mountains in the south. Four local landlords each gave him a plot of land—and on each plot he placed one of his sons and built a village. Garmao was one of those villages. Its plot had been given by Haji Mohsin's ancestor and had passed eventually to three of the mullah's grandsons—one of whom was sitting in the room with me. Eighty-two male descendants of the mullah's son lived in Garmao (Seyyed Umar could not be bothered to count the women), and the plot of land, which had been generous for one man, was now overcrowded. Everyone had either married a cousin from the village or a second cousin from one of the other three original villages.

Dramatic differentials of wealth and power had emerged among the descendants in forty years. Seyyed Umar was a wealthy man and a much more generous host than his chief, Haji Mohsin. In addition to the omelet for lunch, he served me a whole chicken (a much more expensive delicacy here than lamb) with rice, a clear beef broth, a bowl of fried lentils, and soaked bread crumbs in rehydrated goat's curd. I had had difficulty convincing Haji Mohsin to let me have even a little bread for the dog. Seyyed Umar gave me four loaves for Babur, to which I added a little meat when the others weren't looking. But Seyyed Umar's first cousin was in rags. He was older than Seyyed Umar and paralyzed on his right side. He sat in the corner, muttering to himself over a cleft tongue. He begged for money and I gave him some.

It was my tenth straight day of walking and despite the meal, I was beginning to feel run-down. I had had diarrhea for four days, probably a result of giardiasis, and that evening I decided to start a course of antibiotics. My knees were feeling the strain of the hills and I was also preparing to wrap them. I had used all my letters of introduction for this district. The one Haji Mohsin had given me had been pocketed by Seyyed Umar. His illiteracy added a double complication: He could not read the letter and he could not write another one for me.

Seyyed Umar of Garmao

Part Four

The Eimauks are rigid Soonees. In their wars ... they show a degree of ferocity never heard of among Afghauns. I have authentic accounts of them throwing their prisoners from precipices and shooting them to death with arrows; and on an occasion at which a Zooree with whom I had conversed assisted, they actually drank the warm blood of their victims and rubbed it over their faces and beards.

—Mountstuart Elphinstone,

The Kingdom of Kaubul and Its Dependencies,

1815

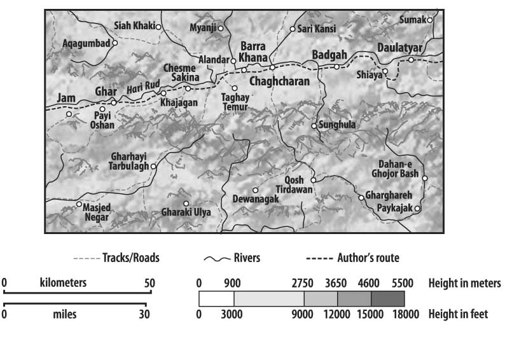

Day 12—Jam to Ghar

Day 13—Ghar to Chesme Sakina

Day 14—Chesme Sakina to Barra Khana

Day 15—Barra Khana to Chaghcharan

Days 16 & 17—Chaghcharan

Day 18—Chaghcharan to Badgah

Day 19—Badgah to Daulatyar

THE MINARET OF JAM

The sun had just hit the valley floor the next morning when I stepped out onto the snow with Babur stepping high beside me. It had snowed all night and virgin powder lay on every side. Seyyed Umar rode on his horse behind me, heavily swathed with blankets. He was puzzled that I refused to ride. The snow was barely a foot deep and the climb up the hill to the pass was an easy one. My staff trembled and creaked in my hand as I moved it through the snow. The crust glittered with shards of light as though fragments of windshield glass had been scattered over the powder.

Halfway up the slope, Babur paused to sniff a jet-black boulder. His long nose thrust gluttonously through our footprints toward the desert floor, seeking the frozen smells of vanished animals. Having completed his survey, he raised his head, stared solemnly into the distance, and lifted his leg. Then, scuttling soil with his front paws to cover his marks, he walked quickly on, head averted, distancing himself from the act. A minute later another boulder caught his attention. We stopped six times in ten minutes.

Babur seemed prepared to examine, mark with urine, and take possession of every meter of the next six hundred kilometers. Only once or twice in my eighteen-month walk across Asia had I felt some magical claim to the territory I touched with my feet. But Babur apparently felt it all the time. The warm stream of urine was set like a flag to mark his new empire. All his movement was conquest and occupation. He seemed ready to ponder and possess every place in the world. He was like a canine Alexander. He had never encountered a space so large or a time so small that it was not possible to sniff and ponder every rock. In this mood, his coat bristling with cold and energy, he strode up to the crest.

The snow was thicker at the pass, and Seyyed Umar was forced to dismount before we descended. At the bottom, in a narrow press of orchards, with smaller tighter hills along a winding river, the scale of the peaks and snowfields was suddenly lost. Here, Seyyed Umar spurred ahead. He was very keen for me to get rid of Babur, whom he thought likely to get us killed by packs of village dogs. He said if I disposed of the dog he'd accompany me all the way to Chaghcharan, but since I insisted on keeping Babur, he regretfully took his leave.

As Seyyed Umar had predicted, dogs swarmed over every orchard wall, teeth bared, and I turned again and again to drive them back. Swinging at another dog, I accidentally clipped Babur and he cowered whimpering at my feet. The day before he'd helped me by barking at the other dogs and trotting along beside me. But from now on whenever I raised the stick to try to protect him, he lay down terrifled, thinking he'd done something wrong and waiting for me to hit him. This left him vulnerable to the angry packs, and I now had to drag his 140-pound frame with me as I backed up the street throwing stones.

We left the village, the dogs fell back, and beside the road the cliffs closed in and the river twisted more aggressively. For twenty minutes we walked alone in a maze of narrow gorges, following a small path. Pale yellow cliffs rose on either side. Apart from the brisk clatter of the river, it was silent. There was no human in sight and no sign of the last twenty-four years of Afghan war.

We came around the edge of a scree slope and saw the tower. A slim column of intricately carved terra-cotta set with a line of turquoise tiles rose two hundred feet. There was nothing else. The mountain walls formed a tight circle around it and at its base two rivers, descending from snowy passes, ran through ravines into wilderness. Pale slender bricks formed a dense chain of pentagons, hexagons, and diamonds winding around the column. On the neck of the tower, Persian blue tiles the color of an Afghan winter sky spelled:

GHIYASSUDIN MUHAMMAD IBN SAM, KING OF KINGS

...

Ghiyassudin was the Sultan of the Ghorid Empire who built the mosque in Herat, the dervish domes in Chist-e-Sharif, and the lost city of the Turquoise Mountain.

I walked around the base of the tower following the tall exuberant chain of polygons that spelled out (though I couldn't follow the geometrical script) the Arabic text of one of the longest chapters of the Koran.

35

It was as finely worked as an ivory chess piece. The octagonal base, the three stories, the remains of the balconies, and the ornate complexity of the geometrical surface were all subdued by the clean, tapering lines and the beige fired brick. The snow on the ground was in shadow. Only the narrow blue line of mosaic, lit by the bright sun, stood out from the coffee-colored hills. The shape of the circular tower was reflected in the curve of the surrounding cliffs. Just as in Chist-e-Sharif, the Ghorids had used the natural landscape to emphasize the color and shape of the building.

Although none of the nineteenth-century travelers to Afghanistan had known of the tower's existence, the Frenchman André Maricq did reach it in 1957 and confirm that it had been the tallest minaret in the world at the time of its construction. Thereafter a number of archaeologists made the difficult journey. But they were unable to decide how the tower related to the mysterious Ghorid Empire, and the Russian invasion of 1979 stopped further visits.

Some archaeologists concluded it had been part of a mosque, called it "the Minaret of Jam," and looked for the Turquoise Mountain in the valley. They discovered very little except, to add to the mystery, a small twelfth-century Jewish cemetery two kilometers from the tower's base. Others, according to Nancy Dupree in 1976, citing the "smallness of the valley, its inaccessibility and its absence of significant architectural remains [argued convincingly] that the Turquoise Mountain had been at Taiwara, more than two hundred kilometers south." Still others asserted that the valley had been a pre-Muslim holy site and that this was a single victory tower, built by the Ghorids to mark the conversion of a lonely and sacred pagan spot to Islam. The archaeologists did, however, agree on two things: the tower was a uniquely important piece of early Islamic architecture and it was in imminent danger of falling down.

By the time of my visit, officers of the Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage had had no reliable report on the tower of Jam for eight months. In the previous decade, much of Afghanistan's cultural heritage had been removed or destroyed; the Kabul museum had been looted and the Taliban had dynamited the Bamiyan Buddhas. No one in Kabul was sure whether the tower still stood.