The Places in Between (6 page)

Read The Places in Between Online

Authors: Rory Stewart

—Mountstuart Elphinstone,

The Kingdom of Kaubul and Its Dependencies,

1815

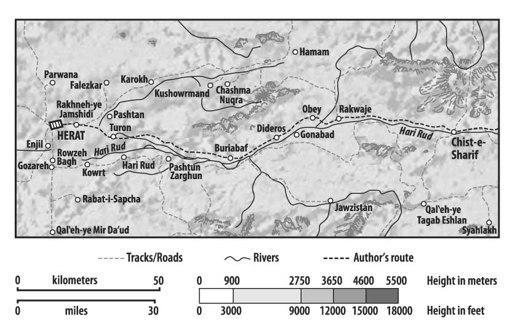

Day 1—Herat to Herat Sha'ede

Day 2—Herat Sha'ede to Turon

Day 3—Turon to Buriabaf

Day 4—Buriabaf to Dideros

Day 5—Dideros to Rakwaje

Day 6—Rakwaje to Chist-e-Sharif

QASIM

We stayed that night in the house of the village headman, Haji Mumtaz. The next morning, after a breakfast of dry

nan

bread and sweet tea, we began again.

Abdul Haq walked with his long, gangling stride, shouting into the static roar of a radio that had no reception. It had only been light for two hours and it was already hot. Sweat spread from the shoulder straps of my backpack, and gathered on my forehead beneath my woolen Chitrali cap. I shifted the heavy stick from one hand to the other and hoped the pain in my left knee would pass. Behind me Qasim shouted at Aziz. They were both limping slightly, probably from blisters, and Aziz was coughing. He adjusted his black-and-white scarf around his neck. Qasim looked at me, smiled, and snapped at Aziz again. I couldn't understand what he was saying, but I noticed that Aziz, although the smallest and apparently weakest of the three men, had been given the others' sleeping bags and Qasim's rifle to carry.

I still knew very little about my companions, but I had learned something about Qasim's status the previous night when Haji Mumtaz met us at his courtyard gate and invited us to stay. We accepted. He asked us to enter ahead of him. We refused; he pleaded; we tried to push him; he struggled, smiling. Finally, it was Qasim who went first, followed by Haji Mumtaz, Abdul Haq, Aziz, and then me. We were led to the threshold of a small mud building, where we wrestled again:

"Please, you are my host."

"Please, you are my guest."

Again, Qasim entered first. There were red carpets from Iran on the floor and some mattresses piled in the corner, but no furniture or decorations. Three men stood to greet us:

"No, no—please sit down ... don't stand for us."

"Of course we must—have my seat. But I insist."

We arranged ourselves on the floor with Qasim seated farthest from the door, and then, after a short pause, one of the strangers turned to Qasim, placed his hand on his chest, and said:

"

Salaam aleikum, Manda na Bashi,

Peace be with you, May you not be tired. I hope your family is well. Long life to you."

Qasim replied at the same time, "And also with you ... may your health be good ... may you be strong ... I hope your house is well."

When Qasim had finished, the man turned to Abdul Haq. "Peace be with you...," he said, "

Manda na Bashi.

" And Abdul Haq replied in kind. After the man had greeted each of us in this fashion, we in turn went round the room saying the same things to each man, one by one. Our host picked up the teapot.

"No, no," said Abdul Haq. "I will pour it."

"I insist—you are my guest."

Abdul Haq grabbed the handle; Haji Mumtaz took it back.

This was a ritual I had gone through almost every night as I walked across Iran. This village had been part of an empire centered in Persia for most of the previous two thousand years. In both Iran and Afghanistan, the order in which men enter, sit, greet, drink, wash, and eat defines their status, their manners, and their view of their companions. If a warlord had been with us, he would have been expected, as the most senior man, to enter first, sit in the place farthest from the door, have his hands washed by others, and be served, eat, and drink first.

4

People would have stood to greet him and he would not normally have stood to greet others. But we were not warlords and it was best for us to refuse honors—not least because no one else's status was clear. Status depended not only on age, ancestry, wealth, and profession, but also on whether a man was a guest, whether a third person was present, and whether the guest knew the others well.

Qasim had not struggled very much before taking the most senior position. He probably thought he deserved it as a descendant of the Prophet, the oldest guest, and the most senior civil servant present. But he could have made more of an effort to hold back. Our host, Haji Mumtaz, showed his manners by ostentatiously deferring to Qasim. The more he did so, the more we were reminded that he had done the pilgrimage to Mecca, was the village headman, and was twenty years older and much richer than Qasim, his pushy guest.

Abdul Haq sat himself at a junior position, folding his long legs beneath him with a natural easy smile. Aziz's poverty was evident from his scrawny frame, ill-kept beard, and poorly fitting clothes. He was only walking with us because he had married Qasim's sister. He moved to the bottom of the room with a defensive scowl. Only I deferred to Aziz, but then I was very low on the scale: visibly young, shabbily dressed, traveling on foot, and, although they might not know this, not a Muslim. But, perhaps because I was a foreign guest and had letters from the Emir, I was promoted after a long debate and made to sit beside Mumtaz. When other senior men from the village entered, we all rose in their honor. But when the servants brought the food, I was the only one to look up. Servants, like women and children, were socially invisible.

Qasim leaned against the wall, his arm draped over his knee, and pushed his overlarge

pakul

cap back on his head. He looked at me with his blue watery eyes, and I thought his smile indicated a sympathy between us that recognized our very different lives, our difficulties in communication, and our shared experience of the journey. He was old enough to be my father, and there seemed something paternal in his weather-beaten face.

"Your Excellency Rory," said Qasim, lingering thoughtfully over the name. "Where are you from?"

"Scotland," I said. There was a pause.

"What do you do, Haji Mumtaz?" I asked.

All I understood from his reply was "in three meters of snow on the road to Chaghcharan."

Having walked across Iran I knew some Persian and they were speaking Dari, a dialect of Persian used across northern Afghanistan. But I had been speaking Urdu and Nepali for a year and I was struggling to resurrect my Persian. I guessed his trucks were stuck in the snow. "Three meters is a great deal," I said vaguely.

"Haji Mumtaz has a great deal of respect for me," interrupted Qasim. "This is because he is a religious man and he knows I am a Seyyed—Seyyed Qasim."

"Indeed," said Mumtaz.

"Of course, Qasim, you are a Seyyed," I said, "a descendant of Muhammad."

"Of the Prophet, Peace Be Upon Him."

"OftheProphetpeacebeuponhim," I added quickly.

There was another pause. Qasim laid his hand on my knee as though he knew me better than he did, and sniffed. "I am a very poor man; Afghanistan is a very poor country. We have no money. Haji Mumtaz has no money. I have no money." I didn't believe him; it looked like a prosperous house.

A servant laid a cloth between us on the bright carpet and unfolded it, revealing thick roundels of

nan

bread. The conversation stopped. Bowls of soup and plates of rice—tender pieces of boiled and salted mutton hidden in the mounds—were brought in. No one spoke during the dinner. We ate quickly with our hands. No one dropped any food except for me, who dribbled rice grains onto the carpet.

When the seniors had finished they passed the leftovers to the men at the bottom of the room, all of whom were younger and thinner than Haji Mumtaz. Aziz, who had already eaten the equivalent of three large plates of rice, continued until he had picked every grain off the two platters, and burped in appreciation. Trays of walnuts and apples and oranges were laid out, more tea was produced, and, after an entirely silent meal, the conversation began again.

The Kurdish areas of Iran had had no vegetables, meat, or fruit in winter, and I usually ate unleavened bread for breakfast and bread and white goat's cheese for lunch and supper. In Pakistani and northern Indian villages, I relied on bread and lentil curry. In Nepal, they ate at ten or eleven in the morning and again in the evening, which did not fit my schedule, so I carried cheap crackers and ate rice and lentils, some nights adding black millet bread. This Afghan dinner had been an impressive feast in a poor and hungry country.

"Where is our guest from, Commander Seyyed?" asked Mumtaz.

"From Ukraine," said Qasim confidently.

"He is a communist then, Commander Seyyed?"

Qasim paused.

"No, I am not," I said in Persian.

"No, he is not," repeated Qasim.

"Is he a Muslim?"

"Yes," said Qasim. I was not. Qasim was saying the first thing that came into his head. He didn't want to admit that he knew very little about me and next to nothing about my country. For the sake of his status, he wanted to show that he was not in charge of a young foreigner in shabby clothes but instead responsible for an interesting and important man. I also suspected that, like many villagers in Iran, Qasim took pleasure making people believe preposterous stories.

When Mumtaz was called outside, I said to Qasim, "I'm not from the Ukraine—I'm from Scotland. The Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union. He will think I am a Russian."

"He will not. Even I don't know where Ukraine is."

Mumtaz reentered. "Does he speak Russian, Commander Seyyed?" he asked.

"Yes, very well," said Qasim. I didn't.

"What is he doing?"

"We are traveling with him because the Emir has instructed us to look after him. We are walking all the way to Chaghcharan."

"Excuse me, Haji Mumtaz," I interrupted, "what are the villages ahead where we will be able to stop for the night?"

"I know," said Qasim. "I'll tell you in the morning."

"And you, Haji Mumtaz," I persisted, "how do you see the route ahead?"

"Well, I suppose Sha'ede, Turon, Mawar Bazaar, Saray-e-Pul, Obey."

They were presumably Tajik Sunni villages, but I had no idea what to expect.

"Look at this," said Qasim to Haji Mumtaz. He turned his foot, revealing a purple and black pus-filled blister on his heel. We had walked less than three hours. I hoped his new boots would be better than his old ones.

"Are you sure you will make it?" asked Mumtaz.

"We will, of course. We are Mujahidin, but him ... I don't know..."

"I think I'll be all right," I interjected. "I have done a lot of walking."

"In Iraq and India and Russia and Japan," Qasim said impatiently, making up countries, "everywhere walking."

"And what is his job?"

Qasim paused. So did I.

"I am a historian," I said.

"He works for the United Nations," said Qasim.

"Is he a doctor?"

"Yes."

"No," I said.

"Well," said Mumtaz, "I've got a pain in my chest. What can you give me?"

"I'll see," I said, opening my pack.

Qasim shouted the question at me again as if he were translating rather than repeating. "Haji Mumtaz has a pain in his chest; what can you give him?" He treated me as though I were an exotic animal he had been selected to exercise for the Emir—a Barbary ape being danced down the Silk Road. He enjoyed talking about me in his loud, dominating voice, and he was pleased when I performed tricks for his friends and produced money or medicine. But he was not so keen on my tendency to speak for myself. Through all this, Abdul Haq remained silent, smiling to himself and occasionally shifting position to stretch his long legs.

"He speaks Dari; do you speak English?" Mumtaz asked Qasim.

"Yes," he replied.

When I had handed over the antispasmodic pills, Haji Mumtaz's sons distributed the mattresses and blankets stacked in the corner of the room and we lay down on the floor to sleep. Haji Mumtaz and his two sons lay down with us to honor us as guests. I was tired, but found it difficult to sleep. Abdul Haq left his transistor radio on all night. All he got was a loud static hiss, but it showed everyone that he owned a radio.

Elders in a guest room

IMPERSONAL PRONOUN