The Postcard (10 page)

The giant open room was hushed and hot and seemed to pull me deep into it with my first step. The sound of the street outside grew muffled and distant.

I gulped for air as if I were trying to swallow the whole room. The only light was from high narrow windows facing the street and were still draped with thick green curtains. It felt like the land of the dead in there.

A few pieces of old furniture were scattered around the lobby. Two soiled sofas of what had once been lime green. A half dozen battered chairs, ripped and stained and sunken. The counter of old polished wood was still visible under a giant paint-splattered canvas sheet. There were stacks of wall trim and molding by the front doors. Sledgehammers were leaning here and there against the walls or on the floor amid electric saws and crowbars and tool chests. The ceiling plaster had crumbled and was lying in gilded chunks around the floor. An elevated machine braced up the ceiling to keep the rest of it from falling, because the massive columns were lying side by side on the floor like giant sticks of chalk, strapped together with bands of steel. Maybe they were going to be saved?

A smell of something earthy caught my nose. Two potted palms, dead and brown, lay on their sides, their soil splashed out and mixing with the rest of the rubble.

Off the left of the lobby behind the registration area and next to the elevator were stairs leading to the upper floors. It was on those stairs that Nick Falcon had first seen the kid he later called Mr. Tall loping down from the floor above. Had he really become the weirdly tall man I’d seen at the funeral? A second caution tape was strung loosely across from the registration desk to the stairs. It was all pretty ghostly. The smell of age and dust and must and mold was everywhere, but the lobby

was

like Beale had written about it.

Okay, I’ve done it. I was going now. The workmen . . .

I turned toward the doors and saw where Nicky might have stumbled in that day to see Marnie.

A single willow.

Nearby were the remains of what I guessed was the newspaper rack that Nick’s father had sent him in to check. Now it was no more than slats of wood and shelves lining a broken stand.

I paused. “Hey, Nicky,” I whispered to the quiet, dusty room. “They’re tearing it down, where you first saw her. The morons.”

I went to the stand and ran my finger over the dusty plank. It shone like polished oak.

Without knowing I was moving, I found myself standing at the bottom of the stairs. Ducking under the tape, I started up.

Jeez! Jeez! Will you stop?

I didn’t. Three flights I went up, one after another after another, around and around and around until I was standing in the hallway of the top floor, my heart pounding against my ribs, my ears burning.

If it was ghostly and quiet downstairs, it was as silent as a tomb up there. I looked at the postcard, imagined the floor plan, and went left to a corner, then right. The carpet was still down, though here and there worn all the way to the wood. The floorboards creaked with every step. Most of the room doors were open. Some rooms were in shambles, others empty, some with the skeletons of bed frames, others with small tables and broken chairs, and all of them thick with dust. People had lived here once. Were they all dead now?

I stopped. Did I really think I’d find Chapter II of the story? Sixty years later? Was it a trap? Was it nothing?

What the heck am I doing here?

Five times I turned back toward the stairs. Five times I turned again and kept walking, each time a little farther than before. When I reached the end of the hallway, I peeked through the narrow crack of the last door. Inside I saw two windows, one on each wall. I looked at the postcard again.

Okay, then.

I was there.

I pushed the door open.

My breath caught in my throat when the door swung all the way in and tapped the inside wall. Sunlight sliced through the blinds at a sharp angle onto the bare floor. The room was empty except for a coating of plaster dust everywhere. I don’t know what I was thinking, but I pulled on the door behind me, then watched as it closed nearly all the way.

I tilted the blinds and looked out.

People crisscrossed the street below. Cars drove by. On the spot where I had been looking up at the room, a man and a woman stood smoking outside an office. He waved his arms, she nodded, then he nodded. A few moments later, they checked their watches, tamped out their cigarettes, and went back inside. They reminded me of the fat man with the silver cigarette case. And the lobby downstairs. And all the steps that had brought me to this room.

The day was going on outside. But inside the old hotel it was like a grave. No, not that. A grave is still, unmoving. I knew about graves. I had just seen one. Being in this room was like standing in a kind of space that — now that I had come — was moving slowly but surely away from the street, away from the city. Away from the present.

I closed the blinds. The air was so heavy and close. I stood for a long time, just sucking in breaths.

What would I say if I were caught? Even if I weren’t, what would I say about this? A sudden thrill went through me. I realized I was both nervous and excited. That feeling spiked and faded, and then I felt sick to my stomach.

You’re breaking the law, doofus. Get out of here.

I didn’t move.

Think about it. The workmen will be back any second. Get out —

I didn’t move much then, either, but I did turn. That was when I saw the bathroom door. It was open a crack. And as dim as the main room was, the bathroom was beaming in full morning light. I guessed there were no blinds on the window. I lifted the card close and found the pinhole again.

It’s in the bathroom.

I walked into the little room. It was empty. The fixtures were gone, their pipes sticking out of the wall. Black-and-white tiles covered the floor. I actually searched all around the window with my hands, then all around the walls for hollow places, knocking at the plaster walls the way they do in movies. Nothing. It was just an empty bathroom waiting to be destroyed. There was nothing else.

Of course, there was nothing else!

It was when I stepped away from the window and turned that I saw an iron grate, low on the wall under the sink pipes. Maybe it was where the heat came in. Or . . .

I turned the card over and saw once more the tiny dots under the two words. I breathed out. “Or air conditioning.”

Trembling, I knelt to the wall. Putting my fingers through the holes in the grate, I pulled on it. It didn’t give. Four screws held it in place. I searched the room until I found a loose nail.

Dad, Dad, you’ll never guess what I did this morning —

I slotted the nailhead into one screw and turned. It began to loosen. Every few seconds, I listened for sounds below me. Hearing none, I kept on. After I removed the third screw, the grate swung down from the wall shaft behind it. I put my hands in.

The shaft was lined in metal and went straight down behind the wall to the floor below. A foot or so below the level of the opening I felt what I first thought was a narrow shelf. Only it wasn’t a shelf, because my fingers felt hinges on the angle nearest the inside wall. Feeling all around it, I discovered that it was shaped like a shallow box. Carefully, I pressed it this way and that and —

snap!

— it came off the wall into my hands. What I pulled up out of the shaft was a metal box an inch deep, hinged, but not locked.

I set it on the bathroom floor and gently opened it.

I fell back on my butt. Sitting inside the box was a large brown envelope.

You’ve got to be kidding me. . . .

The envelope was ripped and filthy, and part of the label was torn off, but I could tell that it was addressed to someone named C. H. Dobbs on 52nd Street. It was postmarked from Singapore.

Dobbs? What the heck . . . !

I took the magazine from my backpack and read the contents. “Dying the Hard Way,” by Chester H. Dobbs, was one of the stories.

I lifted the envelope up out of the box and opened the flap. Inside was a thin stack of paper covered with words in thick, clogged typewriter type. My hands were shaking like the hands of a sick man. I couldn’t believe what I read at the top of the first page.

— II —

THE LONG WAY BACK

By Emerson Beale

I could barely breathe. There must have been twenty pages in all. Making sure I had everything, I replaced the grate, tightened the screws (quite a trick with my quivering hands), and scuttled back to the main room.

I headed for the door, but my eyes couldn’t stop scanning the words on the first page. The hotel was so silent, I stopped. I knew I needed to be gone, to be out of there and far away, but I also knew I couldn’t move until I read a few words. The first page, no more.

Without thinking how a dead man could write a story, I slid down the wall under the window. Its light slanted across the yellowed paper, and I began to read.

— II —

THE LONG WAY BACK

By Emerson Beale

Two weeks after popping out of the blue sedan’s trunk like a cheap magician, I was strolling on a street near the Pier when someone played marimba on my head with a blackjack.

I woke up who knows how many hours later trussed in a marlin net on the deck of a filthy boat. There was a bump on my head the size of a bowling ball. I felt sick all over as if I’d been battered with shovels.

Maybe I was dead.

Maybe I was dead and maybe angels sail you to heaven in stinking fishing boats. But I doubted it.

The smell of the water and the black of the sky and the tiny lights far off told me it was deep in the night, the water was shallow, and we were chugging toward shore.

Two dim shapes stood over me. Not angels. A match flashing onto a cigarette revealed my old yellow-socked friend, Mr. Bones. The redbearded Nazi was planted next to him like a dwarf palm.

“An enemy is what you made for yourself,” Mr. Bones growled. “But don’t get your head too swelled. Some people get Fang mad just by breathing.”

“Fang?” I said, remembering the fat man’s teeth. “Figures. Is he your boss?”

“Yours, too. Only you don’t know it right,” he said.

“Fang is Marnie Blaine’s father?” I said.

“Correck!” Redbeard snapped helpfully.

“What does he want me to do?”

Yellow Socks laughed until he doubled over at the waist, as if he were hinged. “Do? Two things. First, Fang wants you to die. When you’re all done doing that, he wants you to come back to see his daughter just about never.”

“Neffer!” echoed the tubby German.

“Can you be a little more clear?” I asked.

“Ess clear ess a khost!” said Redbeard, wagging an ugly curved dagger at my waist, then my knees, then my chest, then my head, as if it were some kind of pencil, and he was going to draw me with it.

“You see, Falcon, Fang wants to know only one thing about you,” said Skull.

“And what’s that?”

“Fang wants to know that the next time you talk to his daughter, you’re dead.”

It was that speaking style again. I had to hand it to the guy. It was different. All through his little speech his dead smile didn’t change, though his eyes went a little more icy. When he raised his hand to his shoulder and tapped it three times, there came a sudden rapid thwacking from the night air. A burst of wild color fluttered out of it and settled on his coat. It was a parrot.

“Fang! Fang!” it shrieked. “Fanggggg!”

“You fellows know how truly odd this looks, don’t you?” I said. “Maybe I should leave you to your little show and be on my way. I have to feed my mongoose —”

Skeleton’s shoe hiked up my shoulder. He then made a bad impression of someone laughing.

“Do it! It!” he commanded, and Herr Beardbarrel lunged at me with his dagger. But not to kill me. He sliced me out of the marlin net at the same time as Skull whipped out again, with his fist this time, and clocked me on the chin. I tumbled out of the boat and into the water. Splash! Luckily, it wasn’t deep.

“You like a mystery, boy. Well, figure where you are now!” Skull snarled as he spun the wheel and drove the boat away. “Heh, heh!”

I staggered to my feet. “I’ll be back, you know. Marnie will know —”

“That dead is what you are? We’ll deliver the message!”

“Ze messedge!” Redbeard repeated. Then they both hollered, “Heh, heh, heh!” Their cries echoed deep into the still marshes and in my ears long after the sound of the boat had vanished.

I thought, “They just want to scare me, do they? They want to teach me to stay away from the girl? Make me a little wet, a little uncomfortable? Okay, I get it.”

Nuh-uh. It was a bigger than that. My eyes were getting used to the dark now, and I looked around. As Skullhead had said, I did like a mystery, but it was no mystery where he and his pal had dumped me. Coiled roots stretching across the water like dead fingers grasping for life. Water as black as a sea in Hades. The smell of rotting mangrove trees.

“The Everglades!”

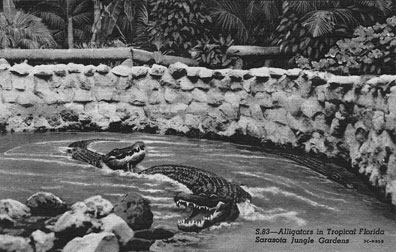

Too bad I didn’t have time to thank the thugs for the complimentary boat ride. There came a faint scooo . . . then a sudden watery sound, a slithering splash, and a breathy growl in the black marsh to my left. I cocked my head. I knew those sounds. They were the calling cards of an alligator, sliding off a mudbank and into the water. Except that when the moonlight glinted off its armored hide, this one turned out to be the largest alligator I’d ever seen. Fifteen feet from snout to tail and a half ton of hungry meanness.

I let the muck suck my shoes off and sloshed quickly to one of the mangrove trees, which I crawled up and jumped at until I grasped a branch. I snapped it off. How it happened is a mystery, but the gator’s first attack — it launched itself like a torpedo across the swamp — didn’t kill me. I whomped the branch on its nose and staggered free. The breath of a thousand tiny wings sounded among the swamp. Hummingbirds! Their whirring was like a glimmering thread of light through the darkness. I imagined Marnie’s voice leading me to safety. I followed. The chomping jaws were seconds behind me. I would have been footless, legless, lifeless in no time, but for those wings and that stick.

“Get back!” I yelled, trying to engage the gator in conversation. “Not talking, eh?” I swung the branch like a baseball bat and caught it between the gator’s jaws as they clamped down.

Unbelievably, the limb didn’t crack. The gator’s teeth sank into the wood and stuck in them for half a second. It was the half second I needed.

Using its head as a diving board, I launched myself into the marsh, crawled up the side of a mangrove trunk as far as I could go, and clung to its branches. For six hours I cooled my heels until well past dawn, when the sun, hot and full and close, lulled the beast to sleep. I climbed down and crept away.

Too bad that wasn’t the end of it. After resting up a week in a little place on Key West, I crawled back to St. Petersburg to confront Fang. I never got close. His minions made sure of that. I saw Marnie once, but only for a second before Skull finally made good on his threat to make an appointment for me. But not with the doctor.

This time it was a travel agent.

When I came to, if you can call it that, my hands were tied with something thick and rough. A wad of oily-tasting rags was crammed into my mouth, and my eyes were squeezed shut behind a blindfold of scratchy wool. I rolled slowly back and forth with the slowly tilting floor.

Where was I?

The constant sound of an engine rumbling and the back-and-forth movement told me I was on another boat. But this one was big. An oil tanker, if I smelled right. An hour later, I’d uncovered one eye and spat out the rag.

The hatch opened, and a short crewman swayed in. He had a nasty look on his face and a nastier wrench in his hand.

“Why am I here?” I demanded.

He looked me up and down.

“Ever hear of the Order, boy?”

“Order? Sure, coffee and a sinker, coming up!”

He tested his wrench against my head, and the wrench won. I went right down. I just had time to hear him — or someone — say a word before I blacked out and struck the floor.

It sounded like, “Oobarab.”

A day later, or maybe it was a week, I heard the engines stop. The great iron vessel hung motionless in the water. I wobbled to my feet when the hull rocked suddenly, and I was down again. “Thanks a lot,” I grumbled. Then there was another shudder, louder this time, then water rushing and men shouting.

A crewman, not the same one, charged into the hold, saw me, stumbled over, and cut my bonds. “The Japanese are attacking!” he yelled. “Get the hell off this ship!”

“The Japanese! Off the Florida coast?”

“You dimwit!” he snarled. “You been out longer than you thought. You’re off Singapore now, boy!”

A third explosion buffeted the tanker, and I knew it was the big one. We took on water and listed to starboard. I crawled up the stairway amid a hail of machine-gun fire and concussions in the air and below the surface. By the time I got to the top, the ship was so far over, the stairs were horizontal. I stepped off the top rung and sank into the water.

To make a long story short, a Navy cruiser raced into the area, the Japanese were driven off, and we were rescued. Two weeks after that, I was in the Army.

Damn the bum eye. I found a troop of soldiers on leave, asked to meet their commanding officer, and enlisted right then and there. I’d say I faked my way through the exam, but they weren’t fussy with the reading chart. They needed me.

“Welcome, Nick,” said a soldier whose platoon I got into. “I’m Private R. F. Fracker. But you can call me Freddie. Nice to meet you, pal.”

I dropped the pages. “Fracker? Fracker! Oh my gosh! Dad! The lawyer! What the —!” I snatched up the pages again.

I made quick friends with Freddie. It had to be quick. I knew him only long enough to discover he was an okay guy, alone in the world, with no family, before he gave all he had for his country. Less than a month into my service, we were landing swift and hard on a crummy little island called Saipan. We just had time to tighten our helmet straps when we were ambushed in a jungle clearing. Forty-five minutes later, I was holding Freddie’s chest together with my hands.

“Listen, Nick,” he said, barely getting the words out, “watch yourself —”

“Don’t try to talk,” I said. “A medic’s coming.”

That was a lie. No one was coming.

“Look,” he said. “The short guy. Curtis. He’s been eyeing you. Don’t know what his beef is. Nick, he seemed mighty interested when he heard your name. ‘Falcon?’ he says. ‘Farmers shoot falcons.’ ‘So what?’ I says. ‘So maybe I’m a farmer,’ he says. Nick, I think he’s choosing his time to get you alone. I’ve tried to watch out for you, but I think I’ll be checking out soon.”

“You won’t —”

“Don’t kid me,” he said, holding up a bloody hand. “I left my insides in the clearing somewhere. I expect I’ll collect them before I leave. They say you’re whole again when you fly up to heaven. Looks like you could use the medic for your shoulder. He won’t of come for nothing.”

I tried to stifle what I was feeling, but it came out anyway, and I began to blubber. “Freddie —”

“Shut up, Nick. And thanks for everything,” he said, more softly now. With an effort he could hardly afford, he opened his collar and ripped the dog tags off his neck. He pressed them into my hand. “Nice coupla weeks, huh? Open the eyes on the back of your head, Nicky. And go find your Marnie.”

He didn’t talk for a while after that. Exhausted and bleeding from my shoulder, I passed out. When I came to, he had died. It was as simple as that.

They patched me up. Not three days later, in another jungle — or was it the same one? — I turned and found myself staring down the barrel of an M1 Garand. The face behind it, squinting and angry, was Curtis’s.

“I gotta do it, you —!” He swore. “I know something about you.”

“Yeah?”

“People don’t like the people you been talking to —”

My mind reeled. “Curtis, put the rifle down.”

“Oobarab told me, and I gotta do it!”

“Oobarab? That’s the second time —”

“The Order told me to, and I gotta.”

“Wait, who’s Ooba —”

In one of those moments that stay with you no matter how long you live, I saw his trigger finger tighten ever so slowly. “Oh, gawww —!”

There was a deafening boom, and Curtis flew up into the air, screaming. It seemed like he went away in different directions at the same time. Something wet splashed my face, my eyes; my head fell back; I was out.

I was shaking all over. The slatted light from the blinds was cutting across the pages now. I couldn’t go on, for right where my fingers held the page his name was written in the margin in the same blue ink as before.

Emerson.

Beside it was a date:

July 14.

On the top of the next page was his name again, written in pencil and traced over a few times with black pen, then blue pen until it was pretty thick. There were two dates there.

Septem. 2, 1947,

and

Novemb. 5.

I quickly flipped through the rest of the pages, but that was the last mark my grandmother made.

I didn’t know what that meant. I kept on reading.

“What day is it?” I asked.

“Day?” The man laughed. “Try year, my lad. It’s been nearly eighteen months since you were discharged into my care. And that, after a year in the Army hospital.”

He tossed me a newspaper.

I read the date through my bandages. “1947!”

Turns out, after the blast on Saipan, I had been in a coma, then in and out of consciousness for quite a while. Infection after infection in between bouts of hallucination and delirium kept me in beds and bandages for thirteen months. When the Army needed my cot for some sap worse off than me, they booted me out, mummy-faced, half crazy, half dead. Without knowing it, I’d been laying up in a flea-ridden hotel near the Singapore harbor run by an old Englishman named Harrow who’d taken pity on me. It was a third-floor walkup in a fifth-rate joint with a bed, a desk, a typewriter, and what sounded like a rat the size of a terrier living rent-free inside the walls.