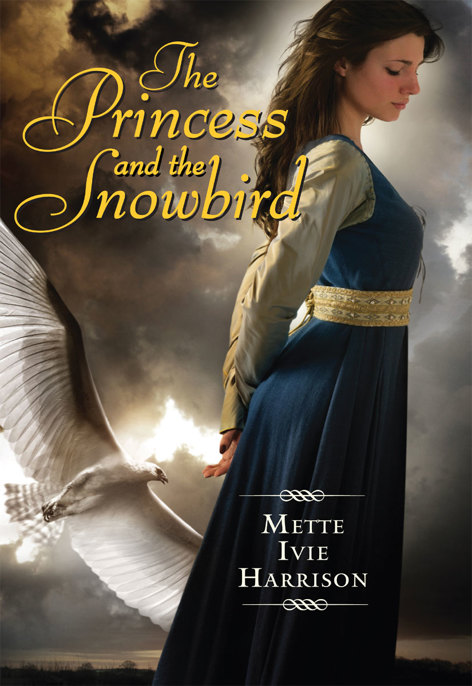

The Princess and the Snowbird

Read The Princess and the Snowbird Online

Authors: Mette Ivie Harrison

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Fairy Tales & Folklore, #General, #Love & Romance

Mette Ivie Harrison

For my mother

The Tale of the Snowbirds

Liva and Jens

Liva

Jens

Liva

Jens

Liva

Jens

Liva

Jens

Liva

Jens

Liva

Jens

The Hunter

Jens

Liva

Jens

Liva

Liva

Jens

Liva

ROLOGUE

The Tale of the Snowbirds

T

HOUSANDS OF YEARS

ago, before humans ruled the world, the snowbirds flew above the earth and watched over the flow of the first, pure aur-magic, spreading the power to all, and making sure that every creature had a share. The name

snowbird

came, some say, because their nesting grounds were in the northern mountain isles, where the snow never melted. Others say they were named for their appearance, for these creatures with huge wingspans seemed pure white except when the sun rose from behind and showed the silver threaded through their feathers.

Like all other creatures, snowbirds had to kill to live, but they were wise and swift and never gave pain to those who died for them. And when a snowbird died, no ounce of its aur-magic was lost. The magic flowed out of it back into the wild, for use by all the living.

But as humans learned magic, the snowbirds began

to disappear. One by one, then dozens at a time. The more the humans spread over the world, the more the snowbirds had to pass out of it. Even the snowbirds who survived laid fewer eggs.

But snowbirds were not the only creatures affected by human use of magic. The moose shrank in size until their antlers were no longer as large as the snowbird’s wingspan. Wolves became tame enough to live in groups rather than as solitary individuals. And some species disappeared entirely.

When no new snowbird chicks had hatched for a hundred years, the leader of the snowbirds, Tulo the Hopeless, called a meeting with all his kind. There were now only six snowbirds remaining—too few to fly together and still keep watch over the land and its creatures—so Tulo assigned each snowbird a region to watch over and heal. It was the only way Tulo could think of to continue to fulfill the snowbirds’ mission, but he was afraid that this was the end, of both the aur-magic and the snowbirds. Soaring alone above the mountains, he feared that he might never again see his own kind.

As the years passed, Tulo felt the death cries of the remaining snowbirds one by one. The first, Frest the Fierce, died after he had poured out waves of magic trying to cure the land nearest the humans, but to no avail. Tulo arrived too late to save Frest, and as he passed over the land, he could sense how it had lost its wildness. It could no longer absorb Tulo’s aur-magic, and he could

do nothing to change that.

The next to die was Rikiki the Swift, for she had gone too far south into human lands and had no strength to return. Her call was faint, a final farewell.

Then Stowr died, without a sound. Tulo never found a trace of the snowbird who had been a childhood friend and with whom he had molted first feathers.

Uvi died on the ground, mauled by the very animal she had tried to offer aur-magic to. The wolf had learned deceit and lust for power from humans and did what wolves would never have done before this time. It called for its pack while the snowbird was most vulnerable, weak and with her wings tucked to herself to keep warm. The pack cut her head and body to pieces, but the wings were left untouched, bits of aur-magic still clinging to them, untaken. When Tulo swooped down, he took the magic to himself, because it was what must be done.

The last was Wara, the youngest of the snowbirds. Tulo had watched over her when she was a chick, and had thought her strong and beautiful. He called to her each time another died, and each time she asked whether she should come to him so that they could mourn together, as the snowbirds had once done. Each time he refused, for he could not see how mourning would change death. And there was still land to be protected with aur-magic against the humans who seemed to take it for their own use and never replenish it.

Then the day came when Wara herself called out in

pain to Tulo, and he rushed to her. She had been struck in the wing by a human arrow as she flew above a newly built village. She tried to fly on, but part of her wing had gone numb. When Tulo reached her, she was clinging to the edge of a cliff, the wind whistling around her in a furor.

Tulo swooped down and pulled her away from the edge. He immediately felt the loss of magic in Wara’s wing. The magic bled out of her, but Tulo could not take it back to himself. It had changed into something tainted by humans, something magic and yet not aur-magic. It was a terrible thing. Tulo did not know how he could help Wara, but he determined at least he would not leave her to die alone.

Tulo tucked his own wings close and gentled Wara with soft words, sung with the melody of the sun and the harmony of the moon. Wara leaned her neck into his. Tulo breathed in her smell, surprised at how much he had missed being with other snowbirds.

But he hated the arrow in her and began to tug at it with his beak.

“Yes, take it out. I will die bleeding freely,” Wara sang back to him, and Tulo admired her courage, though her voice was thready with pain and still high-pitched with youth.

Tulo worked at the arrow until he had pulled it out of her flesh entirely.

She sagged to the ground and took in great, gasping breaths of air.

When she had fallen asleep, and was breathing calmly once more, Tulo examined the arrowhead more carefully. The tip was made from a strange stone, light-colored and brittle, with a cold scent. Tulo did not dare touch it directly, for fear it would numb him as well. But when he closed his eyes and looked only with his magic, he saw that the stone cut two ways, into the flesh and into the aur-magic. The flesh might heal, but the aur-magic had bled away and could not be returned.

While Wara slept, Tulo held the shaft of the arrow in his beak and flew far out over the ocean. He flew until he had reached the iciest part of the world, where no animals lived and even the creatures of the sea kept away. There, at last, he flung the evil weapon down until he heard it shatter on the tip of an iceberg. He then returned to Wara to ease her pain. He could do nothing for the one wing, but he could offer her food and drink, and himself. She rested and sang about the future with her fine voice, though so much had changed.

After many days, Wara recovered enough that Tulo believed she would not die. He coaxed her into trying her first flight without the full use of her wing. She was shaky and lopsided, and Tulo had to fly beneath her to keep her in the air. He dared not try for the nesting grounds, not yet, but they flew away from the humans as far to the north as they could.

Each day they struggled to go farther, to eat, to keep safe from humans. And each day, Tulo fell more in love

with the snowbird whom he had once thought of as a chick. In turn, Wara fell in love with the old snowbird she had once thought angry and wretched. They were the last of their kind, and they expected to die together.

But one morning Wara woke and felt the strains of birth upon her. Tulo had already left in the dark cold of morning to go hunting. Alone, Wara squatted and pressed the egg out of her body. She nudged it with her beak and tried to sense the magic in it, but it was not until Tulo came home that she was sure, for he, too, sensed the great aur-magic within the egg.

“More aur-magic than in either of us. More aur-magic than any snowbird has ever had.” He spoke aloud what neither could fully believe, yet both felt.

“What does it mean?” asked Wara.

Day by day, the two waited. Tulo went for food when he must, but both worked to keep the egg warm.

At last the egg cracked open and the small snowbird emerged.

“What shall we call him?” asked Wara.

“Tululare,” said Tulo, for it meant “the last call of hope.”

This was the story told and retold by those who loved the old aur-magic and hated the new tehr-magic that humans used to abuse the world. From mother to son, father to daughter, grandparent to grandchild the story went, in hope that one day there would be a cleansing of the magic and that the new would return to old.

OOK

O

NE

Liva and Jens

HAPTER

O

NE

Liva

L

IVA DID NOT

think of her age in years, for that was a human habit. She did not even think of her age in seasons, because she did not bother to count them—only humans counted. Liva equally enjoyed the bright sky of summer; the wet, verdant green of spring; the colors of autumn; and the darker sky of winter. She did not long for one while she had the other.

Each season was its own. There were animals who lived through only one season, and those who lived through many, as she did.

One day Liva sat in her cave, practicing birdcalls as she changed from one form to the next: plover, eider, crake, dovekie, grebe, and dipper. She enjoyed the sensation of one form sliding into the next, and each time she went through the repetition, she sped it up. She was caught in the midst of a transformation when she heard the sound of ragged breathing at the mouth of the cave.

Her mother limped toward her, trailing blood, her hind leg torn so that it hung the wrong way.

“Mother!” Liva called out, taking her mother’s shape, the shape of a wild hound, rare in the north. She lunged forward and licked at her mother’s wound, but it was too deep to staunch with only her saliva.

“What happened?” Liva asked in the language of the hounds, for it was the only language her mother could now speak, since she had given the great gift of her aur-magic to Liva at birth.

“A white wolf,” gasped the hound. “Starving. I should have avoided him. But I have my pride.”

“I will kill him,” Liva threatened. She leaned forward and sniffed her mother’s flank, to get a sense of the white wolf. She was excellent at tracking, and she was certain she would find the wolf not long after she left the cave. If he was hungry, he would make mistakes, and though she was not full grown, she could defeat him.

“No, Liva,” said her mother. And then she bit out a cry of pain.

Liva stared at her, frightened. She had never seen her mother unable to control herself this way. “I will!” Liva said. “You cannot stop me. I will do what I want.”

“Please,” her mother whispered, her head low to the ground, though she did not allow herself to fall to her side. “Stay with me, Liva. I need you with me now.”

Liva sighed and put her head under her mother’s. “I will go for Father, then,” she said. “He will kill the

wolf instead, and then he will come and make you well again.”

She said this though her father had also given up his aur-magic to his daughter. He had only enough magic to remain a bear, though he had been born a man. In the forest a bear and a hound could protect a child better than humans could, for a hound was fast and had an acute sense of smell, while a bear was very large and had a roar loud enough to shake the river from its banks.

“No,” her mother said again. “He is too far away for you to go to him. And he has more important things to do. There are lives that depend on him.”

“Your life depends on him,” whimpered Liva. She did not like to show her fear. An animal that showed its fear was weak. That was the law of the forest that Liva had learned since she had first begun to take animal shapes as a small child.

“Those with aur-magic in the south are hunted down and if captured put to death. Your father must help them stay free. But I will recover,” said her mother. “All I need is time. And you.” She nuzzled Liva.

It distracted Liva for a little while. Then her mother quieted and closed her eyes. Her breathing was still sharp and uneven, but Liva thought the hound was asleep.

Liva examined the wound with her eyes, with her nose, and then with her magic. The leg was damaged beyond repair. There were veins that had been cut off, scar tissue forming around muscles that would stiffen them.

Ever since Liva could remember, her mother had refused to take Liva’s magic to shape herself into an animal for play. Liva did not understand why. She had plenty of aur-magic for them both.

Now Liva put a paw to her mother’s leg. The hound winced and tensed up the leg. In that moment, Liva pressed magic into the wound.

But the magic rebounded to her painfully, thrust back by her mother. “Liva, leave it be,” said the hound, opening her eyes for just a moment, as if she were too tired to do so for long.

Liva was confused. “I can fix your wound,” she said. “I can. I can see how to do it.” Could she be afraid that Liva would damage her leg?

“I do not doubt it,” said her mother. “But you must not use your magic on me.”

“It is not just for play,” Liva insisted.

“No, but I’ve had my chance with the aur-magic already.” The hound’s words were slurred, and it seemed to Liva as though she was only partly herself. Surely that must be why she was not making any sense.

“Just a little,” said Liva, persisting. Her father had tried that on her, when she was ill, and he wanted her to take in some broth. She had taken a single sip, just to stop the noise of his pleading. But then she had found that it tasted wonderful, that the warmth that struck her stomach was just what she could have wished for, so she had taken more and more.

“None,” said her mother, growling at her.

So Liva left the cave. She hunted for dinner, and brought back some of the carcass for her mother. Her mother would not touch the meat. She was too weak, and turned to her other side, sleeping heavily. The hound would not stir even when Liva tried to wake her to move closer to the far side of the cave.

Instead Liva pulled the furs over from the far side of the cave. She draped them around her mother’s shoulders, changing into human form briefly because human hands were the most useful for this task.

Then she changed back into a hound and cuddled close to her mother, her back to her mother’s front. She fell asleep for a time that way, until she was woken in the middle of the night by the sound of her mother’s weeping.

The hound was not awake, but she was weeping in pain, tears streaming down her cheeks and into the dark fur around her neck. Liva went out and got water, filling her mouth with it and then returning to put it into her mother’s mouth. After several trips, her mother even swallowed a few of the berries that Liva gathered. The berries her father liked to eat.

Liva thought of her father urgently. He had been gone two months now. Liva hoped that he would return soon. Surely there could not be enough humans with the aur-magic in the south to keep him away longer. The humans she could sense in the village a few hours to the south of

the cave, for example, had no aur-magic at all, only the tehr-magic they used to enslave animals and carve into the natural shape of the land.

The next morning Liva realized that her mother was getting worse. Her wounded leg had become inflamed and filled with pus, and the hound either thrashed with fever or was so still that Liva had to put a paw out to see whether she yet breathed. And still, she would not take any magic.

Again Liva considered going out to find her father, though that would mean leaving her mother alone. She did not know what to do. She was out hunting the next day when her father appeared at the river’s edge.

“Oh, Father,” she wailed in the language of bears. She told him what had happened, weeping.

Her father lifted her to his shoulder.

Liva spoke as clearly as she could. “You must make her take the aur-magic. If I give it to you first, then she will take it. It will not taste like me.” Liva tried to send her magic into her father, for surely he would be sensible.

But she instantly sensed him pushing it away fiercely as he put her down. “No magic,” he said. “Not from you.”

He went back to the cave at a loping run, and there Liva watched as he pressed his mouth to the hound’s in a moment of greeting and love. The hound opened her eyes for just a moment and gave him a small smile. Then the bear lifted her awkwardly to his chest and carried her to

the bed of pine needles in the back of the cave. Over the next several days, he petted the hound when she shivered, and soothed her when she cried out in pain.

Her mother’s fever came down slowly and then the wound on her leg healed, after a fashion. She did not let Liva help it along, not once, no matter how frustrated Liva was at the slow recovery that dragged into winter.

Liva was certain the limp would be permanent. “You should have taken my magic,” she said bitterly one day, after her mother let Liva go ahead for the kill in their hunt. “You needed it.”

“Yes, but others will need your aur-magic more,” said her mother.

“Others—who?” asked Liva.

“You will know when the time has come. Humans have learned to take the aur-magic and never return it. They twist it to their own use and corrupt it entirely. In doing so, they are destroying the wild world. If you are to stop them, you will need every bit of the aur-magic you can gather to yourself. If I took any portion of it, how could I live knowing that it might be my selfishness that hastened the end of the aur-magic?”

But Liva did not care about such larger concerns. She cared about her mother, and about this moment.

So she changed into the shape of a wolf like the one that had attacked her mother and tried to frighten her mother by nipping at her newly healed wounds.

Her mother did not try to stop her but only looked at

her with a steady gaze. “I will be with you as long as I can. I will remember that your magic has a purpose, until you can remember it for yourself.”

“If you could not stop the humans from taking the magic for themselves and ruining it, then how will I do it?” asked Liva plaintively.

“Ah, you are stronger than you know, little one,” said her mother.

Not strong enough to make her mother take her magic, however. And what use was it then?