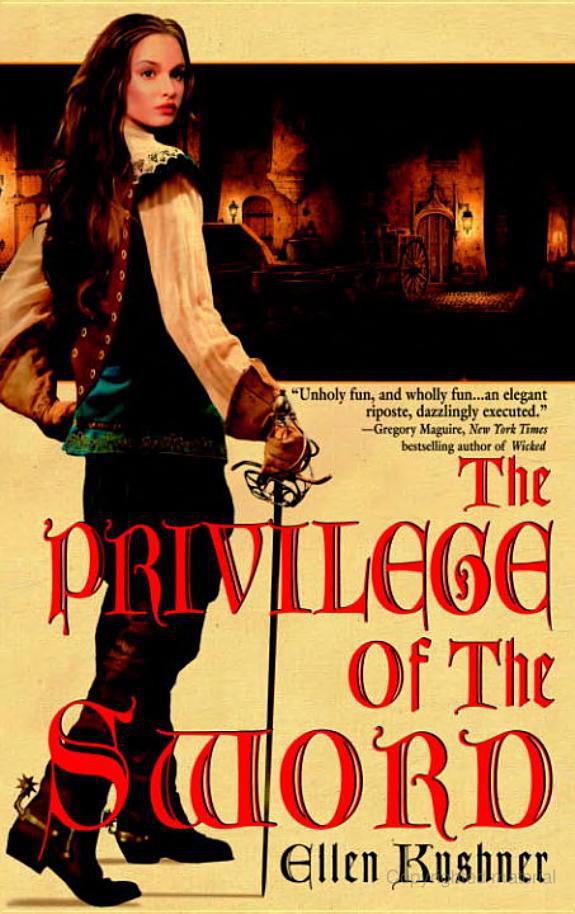

The Privilege of the Sword

Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

chapter I

chapter II

chapter III

chapter IV

chapter V

chapter VI

chapter VII

chapter VIII

chapter IX

chapter X

chapter I

chapter II

chapter III

chapter IV

chapter V

chapter I

chapter II

chapter III

chapter IV

chapter V

chapter VI

chapter VII

chapter VIII

chapter IX

chapter I

chapter II

chapter III

chapter IV

chapter V

chapter VI

chapter VII

chapter VIII

chapter IX

Coda

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Ellen Kushner

Copyright Page

T

his book is

for Delia

and always was

Small pow’r the word has,

And can afford us

Not half so much privilege as The sword does.

—Anon., “The Dominion of the Sword” (1658) If the old fantastical Duke of dark corners

had been at home, he had lived….

The Duke yet would have dark deeds darkly answered.

—Shakespeare,

Measure for Measure

, IV.iii; III.ii All the same, he had no manners then, and he has no

manners now, and he never will have any manners.

—Rudyard Kipling, “How the Rhinoceros Got His Skin”

What a gruesome way to treat one’s niece.

—James Thurber,

The Thirteen Clocks

chapter

I

N

O ONE SENDS FOR A NIECE THEY’VE NEVER SEEN

before just to annoy her family and ruin her life. That, at least, is what I thought. This was before I had ever been to the city. I had never been in a duel, or held a sword myself. I had never kissed anyone, or had anyone try to kill me, or worn a velvet cloak. I had certainly never met my uncle the Mad Duke. Once I met him, much was explained.

O

N THE DAY WE RECEIVED MY UNCLE’S LETTER,

I was in the pantry counting our stock of silverware. Laden with lists, I joined my mother in the sunny parlor over the gardens where she was hemming kerchiefs. We did these things ourselves these days. Outside, I could hear the crows cawing in the hills, and the sheep bleating over them. I wasn’t looking at her; my eyes were on the papers before me, and I was worrying about the spoons, which needed polishing, but we might have to sell them, so why bother now?

“Three hundred and thirteen spoons,” I said, consulting the lists. “We’re short three spoons from last time, Mother.”

She did not reply. I looked up. My mother was staring out the window and gnawing on one end of her silky hair. I wish I had hair like that; mine curls, in all the wrong ways. “Do you think,” she said at last, “that we should have that tree taken down?”

“We’re doing silver inventory,” I said sternly, “and we’re short.”

“Are you sure you have the right list? When did we count them last?”

“Gregory’s Coming-of-Age party, I think. My hands smelt of polish all through dinner. And he never even thanked me for it, the pig.”

“Oh, Katherine.”

My mother has a way of saying my name as though it were an entire speech. This one included

When will you

and

How silly

and

I couldn’t do without you

all at once. But I wasn’t in the mood to hear it. While it must be done and there is no sense shirking, counting silver is not my favorite chore, although it ranks above fine needlework and making jam.

“I bet no one likes Greg there in the city, either, unless he’s learned to be nicer to people.”

There was a sudden jerky movement as she set her sewing down. I waited to be chastised. The silence became frightening. I looked to see that her hands were clutching the work down in her lap, regardless of what that was doing to the linen. She was holding her head very high, which was a mistake, because the moment I looked I knew from the set of her mouth and the wideness of her eyes that she was trying not to cry. Softly I put down my papers and knelt at her side, nestling in her skirts where I felt safe. “I’m sorry, Mama,” I said, stroking the fabric. “I didn’t mean it.”

My mother twisted her finger in a lock of my hair. “Katie…” She breathed a long sigh. “I’ve had a letter from my brother.”

My breath caught. “Oh, no! Is it the lawsuit? Are we ruined?”

“Quite the contrary.” But she didn’t smile. The line that had appeared between her brows last year only got deeper. “No, it’s an invitation. To Tremontaine House.”

My uncle the Mad Duke had never invited us to visit him. It wouldn’t be decent. Everyone knew how he lived. But that wasn’t the point. The point was that almost since I was born, he had been out to ruin us. It was utterly ridiculous: when he had just inherited vast riches from their grandmother, the Duchess Tremontaine, along with the title, he started dickering over the bit of land my mother had gotten from their parents for her dowry—or rather, his lawyers did. The points were all so obscure that only the lawyers seemed to understand them, and no one my father hired could ever get the better of them. We didn’t lose the land; we just kept having to sink more and more money into lawyers, while the land my uncle was contesting went into a trust that made it unavailable to us, along with its revenues, which made it even harder to pay the lawyers….

I was quite small, but I remember how awful it always was when the letters came, heavy with their alarming seals. There would be an hour or two of perfect, dreadful stillness, and then everything would explode. My father would shout all sorts of things at my mother about her mad family, and why couldn’t she control them all, he might as well have married the goosegirl for all the good she did him! And she would cry it wasn’t her fault her brother was mad, and why didn’t he ask her parents what was wrong with the contract instead of badgering her, and hadn’t she done her duty by him? I heard quite a lot of this because when the shouting started she would clutch me to her, and when it was over she and I would often sneak off to the pantry and steal a pot of jam and eat it under the stairs. At the dinner table my father would quarrel with my older brothers about the cost of Greg’s horses or Seb’s tutors, or what they should plant in the south reach, or what to do about tenants poaching rabbits. I was glad I was too young for him to pay much attention to; only sometimes he would take my face in his big hands and look at me hard, as if he were trying to find out which side of the family I favored. “You’re a sensible girl,” he’d say hopefully. “You’re a help to your mother, aren’t you?” Well, I tried to be.

Father died suddenly when I was eleven. Things got much quieter then. And just as suddenly, the lawsuits stopped as well. It was as if the Mad Duke Tremontaine had forgotten all about us.

Then, about a year ago, just when we had begun to stop counting every copper, the letters started coming again, with their heavy seals. It seemed the lawsuit was back.

My brother Sebastian begged to be allowed to go to the city to study law at University, but Seb was needed at home; he was much too clever about land and farming and things. Instead Gregory, who was Lord Talbert now, went to the city to find us new lawyers, and take his place on the Council of Lords. It was expensive having him there, and we were once again without the revenue from my mother’s portion. If we didn’t sell the spoons, we were going to have to sell some of my father’s land, and everyone knows once you start chipping away at your estate, you’re pretty much done for.

And now here was the Mad Duke, actually inviting us to the city to be his guests at Tremontaine House. My mother looked troubled, but I knew such an invitation could mean only one thing: an end to the horrible lawsuits, the awful letters. Surely all was forgiven and forgotten. We would go to town and take our place amongst the nobility there at last, with parties and dancing and music and jewels and clothes—I threw my arms around my mother’s waist, and hugged her warmly. “Oh, Mama! I knew no one could stay angry with you forever. I am so happy for you!”

But she pulled away from me. “Don’t be. The entire thing is ridiculous. It’s out of the question.”

“But—don’t you wish to see your brother again? If I hadn’t seen Greg or Seb for twenty years, I’d at least be curious.”

“I know what Davey’s like.” She twisted the handkerchief in her hand. “He hasn’t changed a bit. He fought with our parents all the time…” She stroked my hair. “You don’t know how lucky you are, Kitty, to have such a kind and loving family. I know Papa was sometimes harsh, but he did care for all of us. And you and I have always been the best of friends, haven’t we?”