The Procrastination Equation (19 page)

Read The Procrastination Equation Online

Authors: Piers Steel

To apply this principle to your life, you need a concrete and exact notion of what needs to be done because vague and abstract goals (such as “Do your best!”) rarely lead to anything excellent. The level of detail required differs from person to person but you should be able to sense when you've got enough. Goals should have a corporeal rather than an ethereal feel—you should be able to sink your teeth into them. “Complete my Last Will and Testament before flying on the 15th” is an achievable goal. “Get my finances together,” not so much.

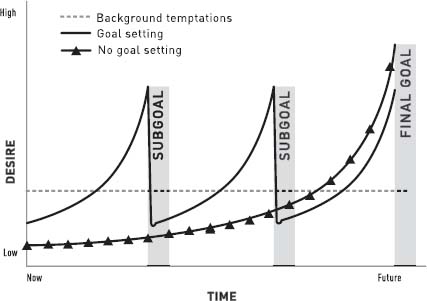

After creating a specific finish line, schedule it soon. You may need to break up a long-term project into a series of smaller steps. Consider the following chart, which represents most work situations. In the background, there is always a buzz of temptation and though it will have its peaks and valleys, on average, we can represent it by a straight horizontal dashed line. Until our desire for work exceeds this constant, we won’t be working. Typically, we allow the environment to set our goals for us and it is pictured by a single goal: the deadline. The triangle line represents a person with no self-set goals, whose motivation is mostly reserved until just before the deadline. What to do? How about artificially moving the deadline closer? The unadorned solid line represents a person who has broken down the task into two earlier subgoals, allowing work motivation to crest above the temptation line sooner. As can be seen, the sum of the parts can be greater than the whole, as the person who sets subgoals works for twice as long as the person who doesn’t.

There are no hard rules for how specific and how proximal your goals must be to be effective. Your success depends on how impulsive you are, how unappealing you find the task, and what temptations you are battling. But keep in mind that too-frequent goals can be cumbersome. Daily goals typically provide a good balance; they are both effective and practical. Still, many find that the hard outer shell of a chore, the first few minutes, remains the initial obstacle. How many times have you put off a task only to realize it wasn’t so bad once you got started? Cleaning, exercising, and even writing are often difficult at first. It is a bit like swimming in the lake by my in-laws' cabin, just north-east of Winnipeg (the coldest city in the world with a population greater than 600,000). The water is deliciously invigorating but, for most, the initial temperature shock is an effective barrier against reaping the subsequent reward. By focusing solely on the initial jump off the dock, I can plunge in and, after a few intense seconds, enjoy myself. An extremely short-term or mini-goal, then, is excellent for busting through such motivational surface tension. Ten-minute goals are an application of this technique, such as the ten-minute clean-up around the house. Consequently, if you have trouble writing, just sit down and type a few words. If you don’t want to exercise, at least get your workout clothes on and drive to the gym. Once you have completed your mini-goal, re-evaluate how you feel and see if you are willing to immediately commit to a longer stretch. Having broken through that motivational surface tension and immersed yourself in the project, you, like most, will opt to continue.

Your final choice is how to structure your goals. Do you prefer

inputs,

the time invested, or

outputs,

what is produced? For exercise, are you going to run for an hour or for five miles? Both are good options. A modest but regular schedule, if it really is regular, produces wonders. B.F. Skinner thought “fifteen minutes [of writing] a day, every day, adds up to about a book every year,” though most professional writers aim to do far more than a quarter of an hour.

61

Others go by the word count; science fiction author Robert Sawyer, for one, writes two thousand words each day, including his blog. Ernest Hemingway combined both inputs and outputs, writing for six hours or producing about five hundred words, a useful strategy. If you have a fruitful day and hit your output quota early, be it words or widgets, reward yourself and go fishing; if the productivity doesn’t come, the input or time requirement ensures that something is produced. To help keep you honest about your productivity, try using free software like

ManicTime

or

RescueTime.

62

They are nifty applications that automatically track your computer work habits, allowing you to easily monitor your activities. How much time are you spending on e-mail? How about web surfing? How much do you actually spend on work? This kind of reality check will make you aware of your productivity and I'll personally vouch that it is useful for winding down an Internet gaming habit.

FULL AUTO

Occasionally, on my ride home from work, I am charged with stopping off at the grocery store to pick up milk or diapers. This side trip entails taking the earlier exit off the highway, which I invariably drive right past. I then need to negotiate a laborious series of travel corrections to get to where I should already be. The problem is that I've done my commute so many times that I'm on autopilot. We have dozens of these automatic routines in our lives, which we can perform even when dead tired. In a mindless blur, we eat breakfast, brush our teeth, and tie our shoes. Despite their zombie-like quality, these routines have power we can tap—the force of habit.

Both the strength and weakness of routines lies in their lack of flexibility. Their weakness is that once we fall into a habit, we tend to follow through even when a change of pace would be beneficial. We go to the same restaurants, order the same food, watch the same shows, without really considering possibly better options.

63

On the other hand, routines are easy to maintain and can be undertaken even when we're exhausted.

64

By intentionally adopting a routine, we can pursue long-term goals even when our wills are weary and temptations abound. We push forward oblivious to other choices, choices that might mean stopping, resting, doing otherwise. The fewer moments of choice there are, the less likely you will be to procrastinate.

65

That is, if you have the right kind of habits. Routines are like Don Quixote’s windmills; they can raise you up to the heavens or drop you down into the mud. Though we have our share of bad habits—reflexively turning on the TV or finishing a bag of potato chips—we can create good ones. We can turn exercising, cleaning, or working into at least semi-automatic routines. Scientific study confirms the benefit of this effort; procrastinators perform as well as anyone else when the work is routine.

66

Building a routine requires activating many of the same precepts as stimulus cues. You want

predictability.

Devise rituals of performance, keeping as many of the environmental variables as stable as possible, especially time and place.

67

Exercise programs, for example, should take place at regularly scheduled times, leaving little guesswork about where and what the fitness activities will be. Like clockwork, every Tuesday afternoon at 5:00, you go and lift weights, and every Thursday morning at 6:00, you go running. Take whatever you have been putting off and specify where and how you intend to implement it. For instance, make a vow: “When breakfast is finished on Saturday morning, I will clean out the storage room.” This seems so easy and simple that it couldn’t work, but it does. When you make an explicit intention to act, the desired behavior just happens. The expert on the psychology of intentions, Peter Gollwitzer, finds that forming intentions almost doubles the chances that you will follow through with almost any activity. The effectiveness of explicit intentions has been scientifically confirmed on everything from cervical screening to testicular self-examinations and from recycling to writing a research report over the holidays.

68

In terms of ease and power, this is as good as it gets. Making an intention is a remarkably accessible back door into your brain; it programs your limbic system to effortlessly act on cue as you see fit. Intentions can even be used to implement other self-regulatory techniques, especially when expressed in an “If . . . then” format. If you have energy issues, make the intention of “

If

I get tired,

then

I will persevere.” If you are easily distracted, it would be “

If

I lose focus,

then

I will move my attention back to the task.” And of course, “

If

I am pursuing a goal,

then

I will use implementation intentions.”

Be warned that when trying to start your routine, you will invent a ceaseless onslaught of excuses not to follow through. You will get sick, go on vacation, have extra work, fall behind elsewhere, and find it ever so convenient to let your schedule slip. Defend fiercely against these slippages! Routines get stronger with repetition, so every time you slack off, you weaken your habit and it becomes even harder to follow through the next time. If you protect your routine, eventually it will protect you.

69

At the start, your regimen will need constant nursing.

70

Some temporary professional assistance can be a good investment; after all, you are investing in yourself. Personal trainers to run you through your paces or professional organizers to help you clean up can help launch you in the right direction.

71

To draft your last will and testament, hire an estate planner or a wills and estates lawyer.

72

They provide as much motivational help as legal expertise, structuring the process to maximize your follow-through. But hired help can’t do it on their own, nor can this or any other book. In the end, the responsibility lies where it has always been—with you.

3. Action Points for Scoring Goals:

This is really saving the best for last. Goal setting—proper goal setting—is the

smartest

thing you can do to battle procrastination. Though every other technique discussed so far has its place, goal setting alone may be all you need. Along with making your goals challenging (chapter 7) and meaningful (chapter 8), follow these remaining steps. Regardless of what other books say, this is what’s proven to maximize your motivation.

• Frame your goals in specific terms so that you know precisely when you have to achieve them. What exactly do you have to do? And when do you have to do it by? Instead of “Do my expense report” it should be “Gather all my receipts, itemize them and record them by lunchtime tomorrow.”

• Break down long-term goals into a series of short-term objectives. For particularly daunting tasks, begin with a mini-goal to break the motivational surface tension. For example, a goal of tackling just the first few pages of any required reading can often be enough to get you to finish the entire text.

• Organize your goals into routines that occur regularly at the same time and place. Predictability is your pal, so open your schedule and pencil in reoccurring tasks. Better yet, use an indelible pen.

LOOKING FORWARD

If only time-sensitive Tom could have read this chapter! He put off booking his hotel and subsequently had a vacation to forget instead of one to remember. He probably didn’t even need all the techniques in this chapter to have changed his fate. Perhaps it would have been enough to set a specific deadline for himself, say, next Thursday night, and frame his intention to act in explicit terms, as in: “Immediately after dinner I will research hotels in the area and book a room.” For good measure, he could have imagined some worst-case scenarios, such as: if he continued to procrastinate, then his room would be far away from the beach and in desperate need of redecoration. Those of you who scored 24 and above on the impulsiveness self-assessment scale in chapter 2 should pay special attention to the techniques here, but almost everyone would benefit from them as well. Though some of us are more impulsive than others, we all can make regrettably impulsive choices.

The fundamental challenge in implementing these steps is that attempts to increase self-control require some self-control to begin with. The obstacle is similar to strength training; in order to initiate the process, we need to be able to lift at least the lightest of the available weights. As for procrastination, the worse it is, the harder it becomes to remedy. The very motivational deficits that create your procrastination also hamper your attempts at change. If you are unable to delay gratification, for example, methods to increase your patience must initially be immediately rewarding in themselves. Otherwise, advice becomes useless shouting from the sidelines, annoyingly extolling you to “do first things first.” If you could simply do that, you wouldn’t need the advice in the first place. Fortunately, most of these techniques are easy to adopt, like turning off your e-mail ding or making those explicit intentions to act. These immediate successes will give you the confidence and the self-control to increase your efforts, all of which will become even easier with practice. From here on out, life becomes better, not harder.

PUTTING THE PIECES INTO PRACTICE

Do or do not do. There is no try.

MASTER YODA

B

efore I get into this chapter, I want to thank you for persevering. People who procrastinate tend to get distracted and turn to other things. So since you have reached chapter 10—and I am assuming you haven’t skipped ahead to the end—you deserve a little praise. After all, the tendency to put off has such a deep resonance in our beings that it is more remarkable when we

don’t

procrastinate than when we do. Having read through the book, you have a good grasp of the underpinnings of procrastination, how it emerges from our brain’s architecture, the ways in which the modern world makes it worse, and what you can do about diminishing it. There is just one last step to putting procrastination in its place. You need to believe what you read.

I can’t really blame you if you are a little suspicious. If you are familiar with self-help books, you have certainly earned some cynicism. There is so much misinformation in the field of motivation—so many promises that don’t deliver—that “What if someone wrote a self-help book that actually worked?” is the premise of Will Ferguson’s international bestselling novel

HappinessTM.

Satirizing the self-help industry, Ferguson invents the character Tupak Soiree, who writes

What I Learned on the Mountain,

a tome that genuinely helps you lose weight, make money, be happy, and have great sex.

10a

Now I can’t promise the last of these, but

The Procrastination Equation

is about making the rest of

What I Learned on the Mountain

a reality. Every technique in this book is based on the bedrock of scientific study, so it had better work. Just flip ahead a few more pages and look at the research I have laid out in the Endnotes.

The Procrastination Equation,

just like

What I Learned on the Mountain,

is still only an inconsequential book if the techniques stay locked inside its covers. In Ferguson’s novel, the challenge was just getting people to read it. For a while,

What I Learned on the Mountain

’s potential effectiveness was derailed, as you might guess, by procrastination. As Edwin, the book’s editor, concludes: “I forgot about procrastinators. Don’t you see? All those people out there who purchased the book or were given it as a gift and still haven’t got around to reading it.” For my book, the requirements are a little steeper, but as you can see, you have already pretty much finished it. To make what you are reading effective, you also need to take its contents seriously. You need to adopt these techniques into your life and start seeing your decision making in terms of that interplay between your limbic system and your prefrontal cortex. To lift the ideas off these pages and into your life, we are going to take one parting look at Eddie, Valerie, and Tom and imagine how they are getting along. You'll see that they are using all these techniques in combination, and thriving because of it. And if you can see yourself doing the same, then you will be able to get your act together, and you will soon be putting procrastination behind you as well.

EDDIE AND VALERIE

After Eddie lost his sales job, he was depressed for a long time—that is, until he met Valerie. She always found a way of putting a smile on his face and it was natural that the two got married. Now in their thirties, with two full-time jobs and a lovable toddler named Constance, they have a wonderful life. But they are always on the run, and lately the demands have been getting worse.

Valerie is often on crushing deadlines, and her home responsibilities take second place when she is in a crunch. She knows how lucky she is to have a job at the local newspaper, but there have been cuts, and she is now doing the work of two people, maybe more. The pressure to meet all her deadlines is serious—this isn’t about career advancement, it’s about staying employed. Eddie has to travel for his job in marketing, which means that he leaves before dawn and is away for days, leaving Valerie in a lurch. When Constance gets sick, all hell breaks loose. She keeps them up at night, and somebody has to stay home with her. When the washing machine breaks down, somebody has to wait for the repairman. Valerie and Eddie feel as if they haven’t had enough sleep in years. And they are right. They know how lucky they are to have two jobs and their little girl, but they are stressed beyond words.

Valerie and Eddie shuttle between work and home like mechanical dolls, always late, grabbing a kiss or a donut on their way out. When they are at home, they worry about the work they are not doing, and so they often go to the computer after the baby is asleep, working through exhaustion late into the night. If the baby is sick, the one who goes to work frets about how she is, and when she is well, they are both checking her out on the webcam at daycare—spending precious work minutes monitoring her well-being. They can hardly handle paying the bills and getting to the pediatrician’s office for checkups and shots. They e-mail each other dozens of times a day, and Eddie has to control himself from texting Valerie from the car on the way to his next meeting.

Eddie promised himself he would clean out the garage last summer, but it’s October, and the junk remains. Valerie has lost control of her vegetable garden, which she started as an altruistic family project but which has devolved into a sad collection of wilted greenery. They are considering canceling their joint membership in the gym—they are both too tired to work out at the end of the day, and mornings reach a level of chaos that drives them both nuts—dressing the baby, exchanging directives about multiple tasks, suddenly full diapers and fussy moments . . . you can fill in the blanks.

This is actually the best-case scenario. It could easily be worse. They face no sudden illness, no job loss, no financial straits, and no tragedy. But Eddie and Valerie’s lives are out of control and they are facing the conflicts that every working couple with kids has to deal with. Recently, Valerie began to feel that she is never in the right place—at work, she thinks she should be home; and at home, she worries about all the work she should be doing. She is feeling frayed and tattered, and is starting to hate her life. Looking for some cheering up, she calls her sister, who listens sympathetically, and then offers a little advice: “There’s this book I've been reading that has a few ideas that might help. Do you want to borrow it?”

Like all such offered books, this one was gratefully accepted but put aside. That is until one stressful sleepless night, when Valerie in desperation decided to crack it open. After skimming through the pages, she noticed the research behind it. “Well now,” she thought. “This stuff has really been battle-tested. Let’s see what I can find for Eddie and me.” Taking some paper and a pencil, she slowed down and made some notes about what she might be able to use.

The next night when Eddie shuffled home, Valerie sat him down and told him flat out, “I'm not happy. Things are going to have to change.”

Eddie sighed and, revealing his low expectancy, said, “I'm not happy either, but this is just the way life is. We can’t change it.”

“You always say that and you're usually wrong,” Valerie replied. “I think there are steps we can take to make our life better. My sister lent me a book and it’s based on scientific research. I hear it has helped a lot of people and we could use some help ourselves. I think we should at least try some of the ideas. For starters, we just need to lay down a few goals.”

Eddie was too exhausted to argue with her, so he played along. “I have a goal,” he said with a small smile, “I want to be happy.”

“They have to be

specific

goals,” Valerie said patiently. “They have to be concrete and doable, something we can get excited about.”

“How about I want to be happy today?” Eddie suggested.

Valerie thumbed her way to the relevant page of the book.“ We start by making some goals about the minimum changes we need to make to stay sane. I need to see my friends more often. I haven’t seen them properly since Constance’s baby shower and talking this over with them always makes me feel like my problems are more manageable.”

Slumping into a chair, Eddie sullenly replied, “And my goal is to hit the gym every weeknight.”

Valerie kept on message. “Get realistic. I think you can spare me one evening every other week. In return, I'm willing to cover you every Saturday morning if you want to exercise.”

“That would be nice,” admitted Eddie. “But I don’t think I am up for handling an evening with Constance on my own.”

Valerie pointed out that he often bathed Constance and put her to bed. “I want you to imagine hitting that gym, Eddie, how good your muscles are going to feel afterward. Also, imagine how much happier I'll be around here if I get some time with my friends. Can you picture that? Take a second and bask in its glow. Great! Now open your eyes and come back to reality. Does that give you the motivation?”

“All right,” Eddie conceded, warming to the idea. “Let’s do it.”

With a little mental contrasting to spur them on, Valerie and Eddie’s goal-setting techniques and “unschedule” (scheduling in realistic leisure time first) do indeed work. Valerie is seeing her friends, and after sharing her problems and hearing others deal effectively with their own issues, she is gaining a little more perspective. She is reassured that Constance will grow up and the economy will get better. It is amazing what a little social support (see

Vicarious Victory

) can do for a person. Eddie himself is glad to get to the gym once in a while. The exercise takes away a lot of his stress. He sleeps a little better and has more energy to tackle the rest of his life (see

Energy Crisis

). Still, a few weeks later, Eddie suddenly announces he has to work late and tells Valerie she has to cancel her plans. When he finally gets home, Valerie is not pleased.

Eddie pleads his case, “Look, I'm sorry you missed your night out but I had work to do and that takes precedence.”

“Night out?” snapped Valerie. “It’s more than a night out. I need that time with my friends. I wouldn’t mind if you had to leave on one of your road trips for work but you e-mailed me fifteen times today while you were at the office.”

“I thought you liked those texts!” retorted Eddie.

Composing herself, Valerie replied: “Here’s what I like. I like face-to-face time with you and with my friends. For every minute you take to text me or send off an e-mail, that’s ten minutes less we have at home. It takes ten minutes at least for you to get your mind back into your work after taking a break.”

This surprised Eddie, but he wasn’t going to give up his text-ing without a fight. “That may be so, but you text too. Besides, I can’t work like a machine at the office. I need my breaks.”

“And why are you tired?” asked Valerie.

“Well, it’s impossible to get to bed early with all the evening work . . .” Then Eddie paused, making the connection. “Oh! Yeah, that might work.”

“If we stop texting during business hours, stop Internet surfing, stop mindlessly checking our e-mails, that'll make at least two extra hours each day for the both of us. Hours we can use for sleep.”

“My mind will zonk out from so much concentration,” said Eddie.

“The book has a few ideas about how to make it work. Start with this. Create a second computer profile for yourself with a different background and layout. Log out of your regular work persona and into this play persona whenever you need a rest. If you aren’t willing to take the minute to do it, you don’t need the break. Here, I got you a present to help you commit.”

“I like presents. What is it?”

Valerie pulled a silver-framed photo from her purse. “A framed picture of Constance and me. Every time you think of slacking off, this will remind you of why we're both pushing ourselves so hard. Remember, this is about us spending more time together as a family. Promise me you'll do this?”

“OK. I'll do it if you do,” said Eddie.

And it works, of course. By ridding their workplace of their major temptations (see

Making Paying Attention Pay

), they have become more productive in the time they are at work and more relaxed when at home. They are starting to wind down for bed and are getting a better night’s sleep, so that they can perform even better (see

Energy Crisis

). To help them get to where they need to be and remind them what this is all about, Eddie keeps that framed photo of his family on his desk (see

Games and Goals

), especially since it reminds him of what he really wants to do—spend more time at home, not texting at the office (setting approach goals, not avoidance goals). It didn’t hurt that Valerie raised the stakes by extracting a little verbal precommitment from Eddie. In the end, they have a little more time than either expected, with both of them hitting the gym at least once or twice a week. Sicknesses, surprises, and other obligations still push them out of their routine, but now they are learning how to push back. They know they are fighting for a life that works. Eventually, Eddie even has the time to do some light reading, which he never used to have the energy for.

After putting Constance to bed, Eddie poured Valerie and himself a cup of tea and plopped into his comfy chair. “I've been looking through this book of yours,” he said, “and I see where your ideas come from.”

Picking up her own cup, Valerie replied, “Well, the secret was in actually following through with them not just reading the book.”

“You're right,” said Eddie, “but I have a suggestion of my own.”

“Go on. I'm listening,” said Valerie.

“Here’s a technique called Let Your Passion Be Your Vocation.”

Her eyes widening in horror, Valerie gasped, “You're not thinking of leaving work to be a golf pro!”

“No, no, no, I'm not thinking that at all. Well maybe a little, but no,” teased Eddie. “But how about this? Getting home earlier is reminding me of how much I used to love to cook. Remember those romantic meals I made for you when we first starting dating? Well, you don’t mind cleaning up as much as I do. So, I'll tell you what: I'll do all the cooking if you do the cleaning.”

Sweetening the arrangement, Valerie added, “If you throw in grocery shopping too, you've got a deal.”