The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (28 page)

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #General, #United States, #Biography, #Biography & Autobiography, #Psychiatric Hospital Patients, #Great Britain, #English Language, #English Language - Etymology, #Encyclopedias and Dictionaries - History and Criticism, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Veterans, #Lexicographers - Great Britain, #Minor; William Chester, #Murray; James Augustus Henry - Friends and Associates, #Lexicographers, #History and Criticism, #Encyclopedias and Dictionaries, #English Language - Lexicography, #Psychiatric Hospital Patients - Great Britain, #New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, #Oxford English Dictionary

The whole saga became then the focus of a long summer month’s work by a host of attachés and vice-consuls and heads of protocol and assistants to senior staff officers, all bickering and wondering whether this harmless old man’s doubtless charming watercolor could ever find its way into the hands of the Princess of Wales.

But it never did. Permission was denied up and down the line—and the whole episode ended in a melancholy way. For when Doctor Minor sadly retreated to his cell block and asked plaintively for his painting back, he was informed with cold hauteur that it had in fact been lost. The letter asking for the painting back is in a spidery, shaky hand—the hand of an elderly, half sane, half senile man—and it was to no avail. The painting has never been recovered.

And there were further dispiriting developments. In early March 1910, Doctor Brayn—whom history will probably not judge kindly in the specific case of William Minor—ordered that all the old man’s privileges be taken away. Minor was given just a day’s notice to quite the suite of two rooms that he had occupied for the previous thirty-seven years, to leave behind his volumes of books, to give up his access to his writing table, his sketchpads and his flutes, and move into the asylum infirmary. It was a cruel outrage committed by a vengeful man, quite likely jealous of the burgeoning reputation of his charge, and angry letters poured in from the few remaining friends who heard the news.

Even Ada Murray—now Lady Murray, since James had been knighted in 1908, recommended by a grateful Prime Minister Herbert Asquith—complained bitterly on her husband’s behalf about the cruel and cavalier treatment that was apparently being meted out to the seventy-six-year-old Minor. Brayn replied limply: “I should not have curtailed any of his privileges had I not been convinced that to leave things as they were was running the risk of a serious accident.”

But neither Sir James nor Lady Murray was mollified: It was imperative, they said, that their scholar-genius friend now be allowed to go home to America, out of the clutches of this monstrous Doctor Brayn, and away from a hospital that no longer seemed the benign home of harmless scholarship but more closely resembled the Bedlam it had once been constructed to replace.

Minor’s brother Alfred sailed to London in late March with a view to resolving the situation once and for all. He had spoken to the U.S. Army in Washington; the generals there said it was possible, providing only that the British Home Office agreed, to have Doctor Minor transferred to the place in which he had been incarcerated very many years before—St. Elizabeth’s Federal Hospital in the American capital. If Alfred agreed to keep his brother in safe custody for the transfer across the Atlantic, then it might well be possible to persuade the home secretary to issue the requisite permission.

Fate was to intervene in a merciful way. By great good fortune the home secretary of the day was Winston Churchill—a man who, though less well known then than he would soon become, had a naturally sympathetic inclination toward Americans, since his mother was one. He ordered his civil servants to send a summary of the case up to his office—a summary that still exists, and offers a concise and intriguing indication of how governments manage their business.

The various arguments for and against the parole of Doctor Minor are offered; the decision is deemed ultimately to rest only on whether, if Minor is still judged to be a danger to others, his brother Alfred can really be trusted to keep him away from firearms during any transfer. The bureaucrats working on the case then slowly but inexorably come to parallel understandings—that on the one hand Minor is not dangerous, and that on the other his brother could be well trusted, if need be. So the recommendation made to Churchill on the basis of this turgid process of exposition and analysis was that the man should indeed be released on parole and allowed to go off to his native land.

And so, on Wednesday, April 6, 1910, Winston S. Churchill duly signed, in blue ink, a Warrant of Conditional Discharge, subject only to the condition that Minor “shall on his discharge leave the United Kingdom and not return thereto.”

The next day Sir James Murray wrote, asking if he might be allowed to say good-bye to his old friend and if he might bring Lady Murray as well. “There is not the least objection,” said Doctor Brayn, smoothly, “and he is in much better health, and will be pleased to see you.” One can almost hear the lifting of the old man’s spirits with the thought that after thirty-eight long years, he was finally going home.

Since the occasion was a momentous one—both for Minor and for England, in more ways than could be immediately understood—Murray had invited an artist from Messrs. Russell & Co., Photographers to His Majesty the King, to take a formal farewell portrait of Doctor Minor, in the Broadmoor asylum garden. Doctor Brayn said he had no objection; the picture that resulted remains a most sympathetic portrait of a kindly, scholarly, and from his facial expression, not uncontent figure, seemingly seated after tea under a peaceful English hedgerow, unconstrained, untroubled, careless of everything.

At dawn on Saturday April 16, 1910, Principal Attendant Spanholtz—a lot of Broadmoor attendants were, like him, Boer former prisoners of war—was ordered to proceed on escort duty, “in plain clothes,” to escort William Minor to London. Sir James and Lady Murray were there in the weak spring sun to say farewell: There were formal handshakes and, it is said, the glistening of tears.

But these were more dignified times than our own; and the two men who had meant so very much to each other for so long, and the creation of whose combined scholarship was now almost half complete—the six so-far-published volumes of the

OED

were packed securely in Minor’s valise—said good-bye to each other in an air of stiff formality. Doctor Brayn offered his own curt valedictory, and the landau rattled its way down the lanes, soon becoming lost to view in an early spring mist. Two hours later it was at Bracknell Station, on the South East Main Line to London.

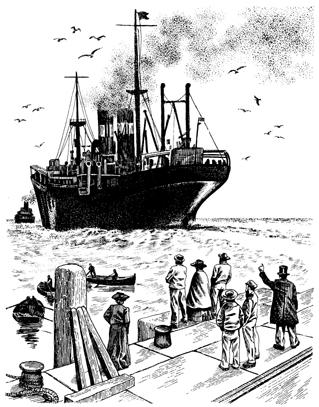

An hour later Spanholtz and Minor were at the mighty, vaulting cathedral of Waterloo Station—much larger than it had been when, no more than a few hundred yards away, the murder that began this story was committed on that Saturday night in 1872. The pair did not linger, for obvious reasons, but took a hansom cab to St. Pancras Station and there caught the boat train to Tilbury Docks. They walked to the quayside where the Atlantic Transport Line’s twin-screw passenger liner S.S.

Minnetonka

lay, coaling and victualing, bound that afternoon for New York.

It was only at dockside that the Broadmoor attendant finally relinquished custody of his charge, handing him over to Alfred Minor, who was waiting beside the ship’s gangway. A receipt was duly offered and signed, just before noon, as though the patient were just a large box or a haunch of meat. “This is to certify that William Chester Minor has this day been received from the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum into my care,” it read, and it was signed, “Alfred W. Minor, Conservator.”

Spanholtz then waved his own cheery good-bye, and raced off to catch his return train. At two o’clock the vessel blasted a farewell on its steam horn and, with tugs yelping, edged out into the estuary of the Thames. By midafternoon it was off the landmark lighthouse on the Kentish coast’s North Foreland and had turned hard to starboard; by nightfall it was in the Channel; by dawn on the next fresh morning, south of the Scilly Isles, and by lunchtime all England and the nightmare that it enfolded had finally receded, lost, over the damp taffrail. The sea was gray and huge and empty, and ahead lay the United States—and home.

Two weeks later Doctor Brayn received a note from New Haven.

I am glad to say that my brother safely made the trip, and is now pleasantly fixed in the St. Elizabeth’s Asylum in Washington DC. He enjoyed the voyage very much and had no trouble from sea-sickness. I thought he walked about too much for the latter part of the voyage. He did not trouble me at night—though I felt much relief on arriving at the dock in New York…. I hope I have the pleasure of meeting you at some future date. My regards to yourself and your family, and best wishes to all the Broadmoor staff and attendants.

Diagnosis

(). Pl.

-oses

. [a. L.

diagnsis

, Gr., n. of action f.

to distinguish, discern, f.

- through, thoroughly, asunder +

to learn to know, perceive. In F.

diagnose

in Molière: cf. prec.]