The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 (22 page)

Read The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

But not all were as practical as these. The government and, indeed, the country were beginning to wake to the fact that Barr’s rosy promises about stout English yeomen were so much eyewash.

It is Tuesday, April 21, 1903. Wes Speers is working in his tent, planning his employment agency, when a thirty-five-year-old Englishman enters, obviously in distress. Behind him comes his wife, slender and dark-eyed, cuddling a tiny fox terrier in her arms. Speers recognizes her at once, for she has been the talk of the camp, gambolling about, caressing her dog, crooning to it as she would to a child. She is a romantic, sees herself as a brave pioneer’s wife, a heroine helping her husband to ultimate fortune

.

Her husband is not so sanguine. He has sunk his money in Barr’s stores syndicate. If he buys a yoke of oxen, a wagon, and a breaking plough he will have no more than seven pounds to his name

.

“I cannot live on seven pounds for a year and a half,” he tells Speers. “What am I going to do for food, for a house, for barns and horses?”

“Why, hire yourself out to Mr. Barr to break sod,” says Speers. “Mr. Barr says he will give you three dollars an acre for the work.”

“But I cannot break sod, dontchaknow. I never did it before.”

“You can learn.”

“And where will I live?”

“Build a sod house.”

“What’s that?”

“A house of sod, built in a ravineside.”

“I don’t think I could possibly do it.”

“Yes, you could. Go ahead and buy your oxen and take your stuff out there. Make some money carrying another man’s goods along with you.”

“Whom shall I get to drive these oxen?”

“Drive ’em yourself!”

The Englishman looks dumbfounded

.

“Come on down tomorrow and we’ll pick out your cattle for you,” says Speers

.

She will be kind to the oxen, the wife says. They will be like household pets. She will feed them bread and butter

.

Did she say

bread and butter?

Yes, she did! A reporter for the

Toronto Star

who has been viewing the scene scribbles the words in his notebook

.

Speers suppresses a smile. His mind goes back to the day when he chased a yoke of oxen up a furrow with a cordwood stick

.

“You’ll have enough to do to feed yourself bread and butter,” he snorts

.

“And we shall have some delightful little piggies,” she burbles. “I shall go out and bustle in the harvest field with my dear husband.”

It is all too much for Wes Speers

.

“Go and buy those oxen and your plough,” he says shortly. “And go ahead if you haven’t got a loaf of bread left. The Government of this country isn’t going to let anybody starve.”

In the hurly-burly of the great tent city, as each family bought its equipment and its animals and prepared for the long trek to Battleford and the Britannia Colony, a few bizarre incidents stood out. Here were a dozen women cooking for their husbands, and all wearing gloves. Here was a six-foot Englishman bathing a fox terrier in a dishpan. Here was one wretched woman, half drunk, rescued from the open prairie by the Mounted Police, rushing through the camp shrieking that Indians had been trying to abduct her.

There was more: a crush of three hundred crammed into the tent post office waiting for mail; when it arrived, there were just forty-three letters … an Englishman spotted invading the male preserve of the local bar and calling, vainly, for an “arf an’ arf … and another, struggling with an ox, striking it in a sudden fury, then begging the animal’s pardon, saying he didn’t mean it.

By Friday the first of the colonists were ready to move out. The news was not propitious. Barr’s transport service had collapsed. There would be no wagon stages for the women and children. Charles May, Barr’s former agent at Battleford, admitting the failure of advance arrangements, had quit and was taking up a homestead of his own. And Barr’s pioneer party, sent out to prepare the new site, had

returned in disarray, its members having lost their way on the prairie, lost their transport cattle in the muskegs, and starved for three days before reaching civilization.

5

Trekking to Britannia

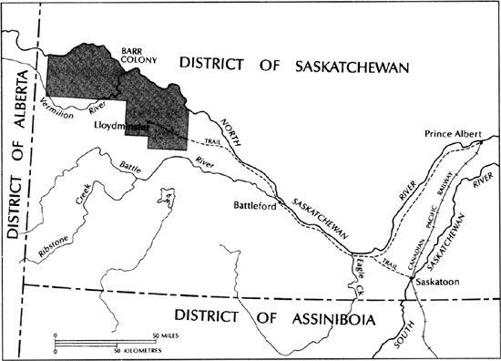

Barr’s original scheme had called for convoys of twenty or thirty wagons to cover the two-hundred-mile distance between Saskatoon and the new colony, with the women and children travelling separately. Now the colonists were forced to strike out individually, without guides or freighters. Each had to find his own way, work out his own salvation in slough or muskeg, and care for his family at nightfall.

Many would be driving horses and oxen for the first time. Some had pocket charts showing that part of the animal’s anatomy where the harness should be attached. Others actually used marking chalk to sketch diagrams directly on the horses’ hides.

Most colonists spent the best part of a week searching out and bargaining for animals, wagons, harnesses, farm equipment, and supplies. The first party managed to get away on April 23, but the last stragglers didn’t set off until May 5. Thus, for the best part of a month,

the trail that led to Battleford and then westward to the Britannia Colony was dotted with wagons.

The Trail to the Barr Colony

Stanley Rackham planned to leave on the twenty-third but found the wagon he had chosen had been sold to someone else. By then no more wagons were to be had, and Rackham had to wait until the

CPR

freight arrived with more. He got away at ten o’clock the following morning, a blistering hot day, found his oxen very soft after an idle winter, indulged in a long rest at noon (as much for the animals as himself), and by four was stuck fast in a bog. A Russian immigrant turned up and helped haul him out.

Rackham’s experience was repeated again and again that Friday. Even before they found themselves out of sight of Saskatoon, a dozen wagons were mired. Matthew Snow, one of the experienced farm instructors hired by Sifton, helped pull them out. But this was only the beginning. Barr’s “road” wasn’t anything more than a deeply rutted trail through the scrub timber made by the Red River carts of the Métis freighters, bringing in furs from Battleford. The entire country in spring was a heaving bog, dotted by sloughs, little streams, and ponds left by the rapidly melting snow.

William Hutchison of Sheffield, whom we last met attending Lloyd’s church service on the

Lake Manitoba

, took the advice of old-timers and delayed his departure until prices came down and the ground was firmer. A day’s delay in Saskatoon, he was told, would mean a gain of two days on the trek. As a result, he and his brother Ted reached Battleford without mishap in a fast five days. Just five miles out of Saskatoon he came upon four teams of oxen, all stuck fast in the mud, exhausted from trying to pull themselves out and now, having given up the struggle, “looking around with wistful eyes for something to eat.” A local farmer took time off from his spring seeding to pull them out. Hutchison’s own ordeal was yet to come.

The colonists had been warned not to carry more than a thousand pounds per wagon; a team of oxen could manage no more. But cart after cart was overloaded – a ton, a ton and a half, even, on occasion, two tons. Some looked like gigantic Christmas trees, hung with lamps, kitchen chairs, oil cans, baby buggies, plough handles, bags, parcels, tools, women’s hats, dogs, and even pianos. Jolted over the uneven terrain, flour sacks burst and coal oil spilled into the foodstuffs. Because of the heavy loads, the women and children could not ride and were forced to walk the entire distance. A bitter wind sprang up; half an inch of ice formed on the ponds; after the heat of early April, it was the worst spring weather in the memory of the oldest freighters. The

women trudged numbly onward; the children cried with the cold.

Wagon after wagon sank to its axles in the white alkali mud of the bogs and sloughs. When that happened, the entire load had to be taken off while the drivers, wading through the gumbo, found a dry spot. Then the team was rehitched to the rear axle and the wagon hauled out with a logging chain. These frustrating delays gobbled up the best part of a day. There were other problems: the horses, up to their knees in mud, would often lie down and die in the swamps. Many more succumbed from lack of feed and overwork at the hands of men who had never handled a team. One freighter counted eighteen dead horses on the trail to Battleford. As J.A. Donaghy, the student missionary, put it, “some never seemed to realize how much a horse must eat to live, and the whole country was full of the finest pasture along the trail. It was painful to see horses staggering under the weight of the harness until they dropped.” There was at least one runaway a day. Some settlers were so fearful of losing their horses that they tied them to trees, but with such a short rope that they could not graze properly and so starved slowly to death.

Barr’s plan to have marquees with fresh baked bread and newly butchered meat all along the route had also collapsed. Now Sifton’s foresight in arranging for large tents at regular intervals saved a great deal of misery. The early birds crowded into these marquees, wolfing tea and porridge, the main provender on the trail. Latecomers had to unload and pitch their own tents nearby.

It was spring in England, but here in this drab land, blue patches of old snow could still be seen in the bluffs of naked poplars. The settlers grew homesick. Robert Holtby, trudging along, mile after mile in the drenching rain – twenty-five miles a day behind the family’s wagon – thought nostalgically of the cricket field at home, green as emerald. Stanley Rackham stared at the brown grass, bleached by the frost, and at the gaunt, lifeless trees, and realized that it was May Day back home; into his mind came a familiar vision of primroses, violets, and cowslips surrounding the japonica-covered cottages in his native May-field.

Yet spring was on its way, a fact made terribly clear by the water gurgling down the slopes and coulées and into the swelling sloughs that barred the route. For latecomers, there were purple anemones poking out of the grasses and in June the sweet perfume of briar rose in the night air. Frogs chorused after dark and wildfowl burst from the. willow groves. The crack shots feasted on rabbit, duck, and prairie chicken.

Suddenly, in the heart of this wilderness – rolling brown hills, white alkali, scrub willow – an astonishing spectacle greeted the trekkers. William Hutchison could scarcely believe his eyes: here, surrounded by furrowed fields, was a Russian village, the houses of trim logs, carefully plastered, neatly arranged along a wide street, their verandahs all gaily painted. This was a Doukhobor settlement, and here the travellers rested. The hospitable Slavs took the women and children into their homes and fed them on fresh eggs and butter.

Hutchison came upon a party of children walking two by two to Sunday School. In their brightly coloured dresses they looked like a living rainbow, and he was reminded, not without a tremor of nostalgia, of a children’s ballet at a Christmas pantomime. He and his brother were impressed by the Doukhobors’ progress: solid buildings and barns, droves of fat cattle, piles of equipment. If these people could make it, so could they! Before they left they took careful note of what they had seen, storing it in their minds for the day when they might benefit from the lesson.

Not far ahead lay the dreaded Eagle Creek ravine. Here was a vast chasm, five miles from rim to rim, with a raging torrent at the bottom, and sides that seemed to be as steep as the wall of a house. Robert Holtby, gazing at it in awe, thought it must have been torn up by a gigantic earthquake. Down this dizzy incline ran the semblance of a track at an angle so steep it seemed impossible to negotiate. Few wagons had brakes. Some tenderfeet actually hobbled their oxen before attempting the descent. As a result, the careering wagons rammed into the rumps of the terrified beasts, overturning the whole and scattering the contents on the slope. The more experienced drivers locked their rear wheels with chains and stood by with long poles to sprag the front wheels should the wagon get away.

The upward ascent was equally dismaying. Some wagons required four horses or three teams of oxen to haul the heavy loads up to the rim. Here Holtby and his family came upon a pitiable sight: a horse had struggled to the top only to drop dead of exhaustion, the ants and hawks already transforming the cadaver into a skeleton. By the time the family reached the government tent at ten that night, Robert was so tired he could scarcely finish his tea, but the incessant squalling of young children kept him awake.

At last Battleford, the midway point on the trail, came into view. Here, in this historic community, the colonists got a glimpse of the old West, of fur traders and Indians, now vanishing before the new invasion. Here were the Mounted Police barracks, white and trim, the

Hudson’s Bay post with its pink roof, and the native school across the river. The little community, untouched until now by successive immigrant waves, sat on the flat tableland between the North Saskatchewan and Battle rivers. A government marquee was already in place; the overflow was quartered in the nearby agricultural hall. Some of the colonists did not venture farther, preparing to homestead in the neighbourhood. The others caught their breath, reorganized their loads, and pressed onward to the colony, nearly one hundred miles distant.