The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 (43 page)

Read The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

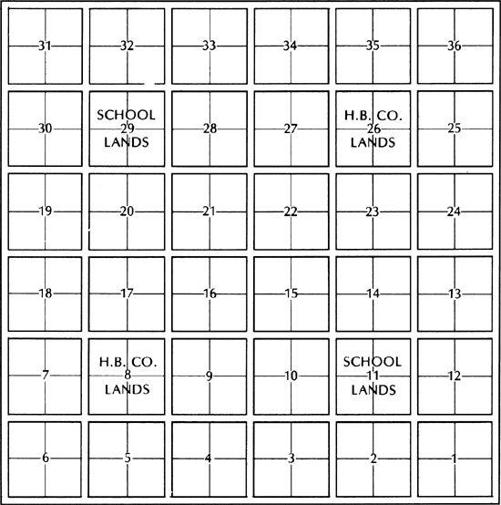

A Prairie Township

3

The Western ethic

Westerners were proud and Westerners were cocky. Their lives were modest success stories, for they had made it when others faltered and went home. And so they were like war veterans who, having survived the battlefield, display their medals and boast about the hard times.

Hard times meant hard work, and that was the key to success. If a man was seen to have worked hard he was admired, as Pat Burns the meat packer was admired. Patrick Byrne, to give him his proper name, so it was said, had made his first million before he could read or write, never stopped working, never understood what leisure was, never for an instant considered sitting back and taking life easy. Like the farmer whom Ella Sykes encountered aboard ship who was not content unless he was buying more and more land, ploughing longer and deeper furrows, Pat Burns was never at ease unless he was expanding. His life was his work; he had no hobbies, read little, wrote few letters, and skipped social functions pleading pressure of business. Bob Edwards claimed Pat Burns’s idea of a good time was “attending the funerals of rival butchers.”

Burns was held up as an example of what hard work could do. As a boy on an Oshawa farm, he was forced to pick his way through a tangle of forest, following three miles of blazed trees to reach the schoolhouse. As a result, he was the least-educated businessman in Western Canada, but also the richest. In Calgary, where he made his fortune, only one prominent businessman in seven had been to business school or college. The majority hadn’t finished high school. Burns didn’t even finish public school.

He had started west with nothing, so poor he was forced to leave the train at Rat Portage and walk the rest of the way to Winnipeg to keep enough money to eat. Later, he thought nothing of walking another 160 miles to locate a homestead at Minnedosa. Then he went farther west. To earn money to buy livestock, he worked blasting rock for the

CPR

. After that he never worked for anybody but himself.

He started as a cattle drover and freighter in the foothills under contract to the railway and raised himself bootstrap by bootstrap – a beef contract here, a hog contract there. An old friend from Kirkfield, Ontario, William Mackenzie, the railway contractor, gave him another boost; by 1890 he was supplying beef to the Mackenzie and Mann railway system, soon to become the Canadian Northern. He never looked back, never stopped working, set no finite goals for himself,

seeing instead a future that had no limit to progress. In that sense he typified the West.

Since he had no end point in sight, he simply arranged for his empire to grow with the country. In him was distilled all the optimism of the new frontier. Warm and genial, he had supreme confidence in himself and in the West. There wasn’t a neurotic bone in his body. An early riser, he could catnap any place, any time; a good listener with a good memory, he was never brusque or impatient. He preferred to conduct his business in person and was shrewd enough to seize what the West was offering. As early as 1885, with the

CPR

scarcely completed, he grasped the opportunity it offered and so became the first man to move hogs by rail. When news of the Klondike strike hit the world in 1897, he lost not a moment in shipping cattle to Skagway and rafting them down the Yukon to the goldfields.

With his Klondike profits, he moved in 1902 into real estate: a ranch, a slaughterhouse, a business block, several butcher shops. Now he was producer, manufacturer, and sales department all rolled into one. Soon he added dairy products, vegetables, and fruits to his list of merchandise. By 1906, he had markets in sixty Western towns and headed the largest corporation on the prairies dealing with livestock and meat. He was not a Calvinist but an Irish Catholic, but, as one Chicago cattleman said of him, “he resembled the proverbial Scotsman who keeps the Sabbath Day and everything else he can lay his hands on.”

He stood five feet seven in his socks – a swarthy man with piercing, deep-set eyes, broad shoulders, and a long torso that made him seem taller than he was. He walked with a rolling gait but despite his short legs could beat anybody in a foot race. He loved to race, for he was incurably restless, incurably competitive. He found it impossible to sit still, physically or financially. He was forever getting up and pacing about his vast eighteen-room mansion of oak and sandstone, designed by Francis Mawson Rattenbury who later built Victoria’s famous Empress Hotel. He was never idle, a man on the move who believed that money, too, should never be left idle. He had no sooner completed one project than he invested the profits in the next. When his first slaughterhouse burned down, he built a larger one. Years later, fire took another slaughterhouse. Before the flames had died, it was said, he was planning a bigger replacement.

In a province where businessmen liked to think of themselves as rugged individualists, few were as rugged as Pat Burns. Listen to him in 1907, defending his credo before an Alberta commission looking

into possible monopolies in the meat business: “I am running my own show, standing on my own bottom, having nothing to do with any person else, and don’t want to. I never squeezed a man and for that reason have all the business I want and I pay the highest prices. Certainly I like opposition. I like it because it makes business better, and the more the merrier.” With that spirited response, Burns emerged from the hearing unscathed.

No one else had such an influence on the livestock industry in the West. Burns opened up new avenues of Canadian trade to Australia and Japan, shared the export trade to Britain, found new markets in the East, and built large packing houses in Calgary, Edmonton, and Vancouver. His company was one of the largest of its kind in the world, with branches in Liverpool and Yokohama. Like Robert Chambers Edwards of the

Eye Opener

, he became a Western icon, the symbol of a nation within a nation where, it was devoutly believed, any man could rise to the top from the humblest beginnings if he had faith in the country and was prepared for hard work.

Like Burns, Westerners thought of themselves as a special breed. One former Scot, who had grown wealthy farming near the Qu’Appelle Valley, went so far as to boast to an English reporter that Westerners were the physical, moral, and intellectual superiors of any in the Old Country. It was that kind of remark that caused the

Scotsman

of Edinburgh to comment on the “savage arrogance” of the Western Canadian farmer. Yet the settlers had reason to be smug. In the Old Country they had been the prisoners of class. Here they were as good as any man. The first thing that struck the English who came west was (to quote one) “that every Jack seems to be as good as his master – or to think he is.” J.B. Bickersteth, a Church of England missionary, noted that everybody seemed to be in a conspiracy to make the greenhorn understand that he had reached a classless society where each man or woman was the social equal of his neighbour.

“I call upon people who would not have taken any notice of me in England,” one woman told Ella Sykes. Westerners learned early the virtue of co-operation. Social custom required that any stranger caught by darkness or weather several miles from a settlement was to be fed and his horse stabled by the nearest farmer. It was this attitude that helped set the mood for the co-operative movement on the prairies.

Almost every immigrant had seen the West as the Promised Land, a phrase used more than once in the pamphlets of the Immigration Department. The Americans came for profit, the Slavs to escape

penury and authority, the British to flee the smoky cities and return to the agrarian past. But the West was not the sylvan paradise for which so many had hoped; nor was it a get-rich-quick gold mine of a country. The farmer was not necessarily the noblest of God’s creatures, and the “garden city” of the nineteenth century was a long cry from the dusty, manure-befouled streets of Calgary and Edmonton or the wretched slums of Winnipeg.

Those who sought Utopia on the Canadian plains were doomed, like the Doukhobors, to disappointment. The Trochu colony of Alberta, an idealistic French community of bachelor aristocrats founded near Three Hills by Count Paul Beaudrap, lost its homogeneity with the coming of the railway. The model socialist community founded by striking French coal miners at Sylvan Lake, near Red Deer, succumbed to “an insane desire to get rich quick.” The small band of a dozen Adamites, disciples of James Sharpe, who claimed to be Jesus Christ himself, were quickly shoved back across the border for bringing firearms into the country. And that charismatic and occult sect known as the Dreamers, who settled near Medicine Hat in 1907, quickly broke up in the wake of a sensational murder trial, which disclosed that these apostles believed they were entitled to kill any enemy revealed to them in their sleep. Only the Mormons, who fled religious persecution in the States, and the Mennonites persevered because, like other successful immigrants, they discarded visions of Utopia, irrigated the land or worked the black prairie soil, and tended to their own affairs. For these hard workers the Westerners cast aside their prejudices. That was part of the Western ethic.

The personal pride that Westerners felt in themselves was translated into a local and regional pride. Newcomers, visitors, and old hands talked of the West as if it were a separate state. Certainly the clear demarcation of the Cordilleran spine on the West and the Precambrian schists and muskegs on the East gave it a clear outline. But it was more than a geographical entity; it was also a state of mind and an attitude. To the Westerner, anything was possible; there was no problem that could not be surmounted; the future was rosy and never ending. Had he not proved it?

There has never been such a period of optimism in Canada as there was in the years before the Great War. It was, of course, part of the worldwide innocence that was shattered forever by the cannon of 1914. But in the Canadian West it reached heights unattained elsewhere. We have not again known that giddy buoyancy, that boundless enthusiasm that rippled across the plains in ever-widening circles

touching, eventually, both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The West did not suffer, in those heady days, from the so-called Canadian inferiority complex.

Visitors to the West were caught up in the enthusiasm and remarked on it. John Foster Fraser reported in 1905 that “there are not half a dozen wooden shacks on the prairie, called a ‘town’, where the inhabitants do not believe that in a very few years that town will be one of the most famous and prosperous cities in the entire Dominion.” The following year another traveller reported: “Every Winnipegger is afire with zeal and confidence.” And a reporter for the Saint John

Telegraph

exclaimed in 1910: “We have not met one individual who is not full of the most absolute faith in the country.”

It was generally accepted that the West would outstrip the East and that Winnipeg would one day become the capital of Canada. By 1906, the Calgary

Herald

predicted, the majority of Canadians would probably be living west of Lake Superior. The

Canadian

magazine, a Toronto publication, was predictably more cautious. It estimated that the balance wouldn’t shift until 1931.

By 1905, the Toronto papers had ceased to grumble about Western “kickers.” The West was bringing prosperity to the whole country, and the eyes of the world were fastened on Canada. For decades the world had ignored the new nation. Now a stream of books and newspaper articles focused not only on the West but also on the entire Dominion. The regional pride that Westerners felt was being transformed into a new nationalism. Since 1867, Canada had been an awkward entity, its Pacific province cut off from the East by two thousand miles of empty prairie. Now Canadians saw their Dominion with new eyes. The vacuum was filled; a new heartland had emerged, vibrant, confident, prosperous.

One longs in vain for the same yeastiness, the same bubbling enthusiasm, the same rock-like confidence in the Canada of today.

4

Bob Edwards and the

Eye Opener

No other Westerner managed to capture the buoyant, restless, iconoclastic spirit of the West in the way that Bob Edwards did. The country has never known – probably never will know – a publication as outrageous, as irreverent, or as ebullient as his personal creation, the Calgary

Eye Opener

. Among the so-called legitimate dailies, the

Calgary

Herald

had no rival for flamboyance. But there were times when the weekly

Eye Opener

made the

Herald

seem like a Sunday School tract.

The essence of the paper’s appeal was that in an era when journalists could be bribed for a pittance, when newspapers shamelessly distorted the truth, when publishers were caught in political scandals, when editors kowtowed to politicians, stuffed shirts, property interests, and advertisers, Robert Chambers Edwards was ruthlessly honest, ruggedly independent, and totally fearless. More than that, he was very funny.