The Prospector (23 page)

Authors: J.M.G Le Clézio

Around noon, having climbed up to the Commander's Garret in the Corsair's ruined watchtower, I discover the ravine. At the upper end of the valley. It hadn't been visible because of a rockslide that is hiding its entrance. In the light of the sun at its zenith I can clearly see the dark gash it makes in the flank of the hill to the east.

I carefully note its location in regard to the trees in the valley. Then I go and talk to the farmer, near the telegraph buildings. His farmhouse, as I was able to see when I arrived on the road from Port Mathurin, is a rather precarious shelter from the wind and rain, half-hidden in a declivity in the land. As I draw near a great dark shape stands up, grunting, a half-wild pig. Then it's a dog, fangs bared. I recall Denis's lessons in the old days, out in the fields: a stick, a stone are useless. You need two stones, one you throw and the other you threaten with. The dog backs away, but defends the door to the house.

âMister Castel?'

A man appears, bare-chested, wearing fishermen's trousers. He's a tall, strong black man with a scarred face. He pushes the dog aside and invites me to come in.

The inside of the farmhouse is dark, smoke-filled. The furniture consists of a table and two chairs. At the back of the only room, a woman dressed in a faded dress is cooking. At her side is a little girl with light skin.

Mr Castel invites me to sit down. He remains standing, listens to me politely as I explain what I've come for. He nods his head. He'll come and help me from time to time, and his adopted son Fritz will bring me a meal every day. He doesn't ask me why we are going to dig up the ground. He doesn't ask a single question.

This afternoon I've decided to continue my explorations further south at the upper end of the valley. I leave the shelter of the tamarind tree, where I've now set up camp, and follow the Roseaux River upstream. The river winds along on the sandy bed, forms meanders, islands, a narrow stream of water that is only the exterior aspect of an underground river. Higher up, the river is a mere trickle running over a bed of black shingles in the middle of the gorge. I am already very near the foothills of the mountains. The vegetation is even sparser, thorn bushes, acacias and the ever-present screw pines with leaves like cutlass blades.

The silence is heavy up here and I try to walk, making as little noise as possible. At the foot of the mountains the stream splits into several sources in schist and lava gullies. Suddenly the sky grows dark, it's going to rain. The drops come large and cold. In the distance, down at the very bottom of the valley, I notice the sea veiled in the storm. Standing under a tamarind tree I watch the rain making its way up the narrow valley.

Then I see her: it's the young girl who saved me the other day when I was delirious with thirst and fatigue. She has a child's face, but she is tall and svelte, wearing a short skirt, as is the custom for Manaf women, and a ragged shirt. Her hair is long and curly like that of Indian women. She's walking along the valley, head down because of the rain. She's coming towards my tree. I know she hasn't seen me yet and I'm apprehensive about what will happen when she notices me. Will she cry out in fear and run away? She walks silently along with the supple movements of an animal. She stops to glance at the tamarind tree, she sees me. For an instant her smooth, handsome face betrays wariness. She stands still, balanced on one leg, leaning on her long harpoon. Her rain-soaked clothes are clinging to her body and her long black hair makes her copper skin seem more luminous.

âGood day!'

I say that first, to drive away the anxious silence that reigns up here. I take a step towards her. She doesn't move, just stares at me. The rain is running down her forehead, her cheeks, down her long hair. I notice she's holding a vine bandolier strung with fish in her left hand.

âHave you been fishing?'

My voice rings out oddly. Does she understand what I'm saying? She goes as far as the tamarind tree and sits on one of its roots, sheltered from the rain. She keeps her face turned towards the mountains.

âDo you live in the mountains?'

She nods her head. In a lilting voice she says, âIs it true you're looking for gold?'

I am less surprised by the question than by the language. She speaks French with hardly any accent.

âHave you been told that? Yes, it's true, I am looking for gold.'

âHave you found any?'

I laugh.

âNo, I haven't found any yet.'

âAnd do you really believe there's gold around here?'

I find her question amusing.

âWhy? Don't you believe so?'

She looks at me, her face is smooth, fearless, like that of a child.

âEveryone is so poor here.'

Again she turns her head towards Mont Limon, which has vanished in the cloud of rain. For a moment we watch the rain falling without saying anything. I look at her wet clothing, her slender legs, her bare feet resting nice and flat on the ground.

âWhat's your name?'

The question has slipped out almost in spite of myself, maybe so I can hold on to something about this strange young girl who will soon disappear into the mountains. She looks at me with her deep, dark eyes, as if thinking about something else.

Finally she says, âMy name is Ouma.'

She stands, picks up the vine on which the fish are strung, her harpoon, and leaves, walking quickly along the stream in the slackening rain. I see her nimble silhouette leaping from stone to stone, just like a young goat, then it fades into the underbrush. It all happened so fast that it's difficult for me to believe I haven't imagined that apparition â that beautiful, wild, young girl who saved my life. The silence is making my head reel. The rain has stopped altogether and the sun is shining brightly in the blue sky. The mountains seem even higher, more inaccessible, in the sunlight. In vain I scan the slopes of the mountains, over in the direction of Mont Limon. The young girl has disappeared, she's blended in with the walls of black stone. Where does she live, in which Manaf village? I think of her strange name, an Indian name, whose two syllables she'd made ring out clearly, a name that troubles me. I end up running back down to my camp under the old tamarind tree at the bottom of the valley.

In the shade of the tree I spend the rest of the day studying the maps of the valley and marking the places I'll need to probe with a red pencil. When I go out to locate them on the terrain, not far from the second point, I can clearly make out a mark on an immense boulder: four regular holes chiselled into the rock in the shape of a square. Suddenly I recall the formula in the Mysterious Corsair's letter: âLook for

:

:

'. My heart starts beating faster when I turn to the west and discover that the watchtower of the Commander's Garret does indeed lie on the diagonal of the north-south axis.

Late in the day I find the first mark of the anchor ring on the slope of the hill on the eastern side.

As I'm trying to establish the east-west axis that cuts across the Roseaux River at the edge of the old swamp, I find the anchor ring.

Walking along with compass in hand, my back to the sun, I pass over a dip in the ground that I think is the bed of a former tributary. I reach the cliff on the east side, very sheer in that particular place. It is almost a vertical wall of basalt that is partially crumbled down. On one of the rock faces, up near the top, I see the mark.

âThe mooring ring! The mooring ring!'

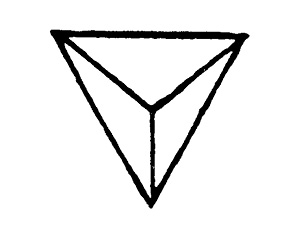

Repeating these words in a hushed voice I try to find a way to reach the top of the cliff. The stones roll out from underfoot, I grab hold of shrubs to pull myself up. Once near the top I have a hard time finding the rock wall with the mark. Seen from below, the sign was clear, in the shape of an inverted equilateral triangle, exactly like anchor rings in the days of the corsairs. As I'm searching for that sign, I can feel my blood beating in my temples. Could I have been the victim of an illusion? I see angular marks caused by past fractures on all the rock faces. I examine the edge of the cliff several times, slipping on the loose rocks.

Down below in the valley young Fritz Castel, who's come to bring me my meal, has stopped at the foot of the cliff and is looking up. I understand my error when I see the direction in which he's looking. The rock faces all resemble one another and I'm sure the ones I'd spotted are higher up. I climb higher and reach a second level that is also where the vegetation stops. There, before my eyes, on a large black rock, shines the magnificent triangle of the mooring ring, etched into the hard rock with a regularity that only a chisel could achieve. Trembling excitedly, I step up to the stone, brush my fingertips across it. The basalt is warm with light, soft and smooth as skin and I can feel the sharp edge of the triangle that is inverted, like this:

I will surely find the same sign on the other side of the valley by following a line running east-west. The other slope is at quite a distance, even with a telescope, I wouldn't be able to see it. The hills on the western side are already in shadows and I put off the search for the other mooring ring until tomorrow.

When young Fritz has left I climb back up. I stay there, sitting on the crumbling rock, gazing out on the expanse of English Bay being overtaken by the night. For the very first time I have the feeling that I'm not seeing it with my own eyes, but with those of the Mysterious Corsair who came here a hundred and fifty years ago, who drew up the plan of his secret in the grey sand of the river and then allowed it to fade away, leaving only the marks carved in the hard stone. I imagine how he must have held the hammer and chisel in order to engrave this sign and how the pounding of the hammer must have rung out all the way to the other end of the deserted valley. In the serenity of this bay, where a quick ruffle of wind passes from time to time, bearing along with it snatches of the rumbling sea, I can hear the sound of the chisel chipping at the stone echoing in the surrounding hills. Tonight, lying on the bare ground between the roots of the tamarind tree, wrapped in my blanket just as I used to be out on the deck of the

Zeta

, I dream of a new life.

Today at the crack of dawn I'm standing at the foot of the western cliff. There is barely enough light to make out the black rocks and in the crook of the bay the blue of the sea is translucent, lighter than the sky. Like every morning I hear the cry of seabirds flying over the bay, squadrons of cormorants, gulls and boobies calling out hoarsely on their way to Lascars Bay. I've never been so happy to hear them. It seems as if their cries are greetings they are sending to me as they pass over the bay, and I too cry out to them in answer. A few birds fly right over me, sterns with vast wings, fast-flying petrels. They circle round near the cliff, then go off to join the others out at sea. I envy their lightness, the speed with which they slip through the air, free of all ties to the earth. Then I see myself glued to the floor of this sterile valley, spending days, months scouting out territories that the birds' eyes have scanned in an instant. I love watching them, I partake in a bit of their beauteous flight, a bit of their freedom.

Do they need gold, riches? The wind is enough for them, the morning sky, the sea abounding in fish and the emerging rocks, their sole shelter from storms.

Guided by my intuition I make my way over to the black cliff where I'd noticed crevices from the hill on the other side of the valley. As I pull myself up with the aid of shrubs, the wind buffets, inebriates me. All at once the sun appears above the hills in the east â magnificent, dazzling, lighting sparkles on the sea.

I examine the cliff bit by bit. I can feel the burn of the sun growing steadily hotter. Around midday I hear someone call. It's young Fritz waiting for me below, near the camp. I climb back down to rest. The enthusiasm I felt in the morning has waned considerably. I feel weary, discouraged. In the shade of the tamarind tree I eat the white rice in Fritz's company. When he's finished eating, he sits waiting in silence, gazing out into the distance with that impassive attitude that is characteristic of the black people from here.

I think of Ouma, so wild, so lithe. Will she come back? Every evening before sunset I walk along the Roseaux River until I reach the dunes, looking for traces of her. Why? What could I say to her? Even so, I think she's the only one who understands what I've come here in search of.

Tonight, when the stars appear one by one in the sky, to the north, the Smaller Chariot, then Orion, Sirius, I suddenly understand where I've gone wrong: when I plotted the east-west axis, starting from the mark of the mooring ring, I was using the magnetic north as my compass indicated. The Corsair, who drew up his maps and marked off the rocks, didn't use a compass. He undoubtedly used the northern star as a reference point and it is in relation to that direction that he established the east-west perpendicular. Since the difference between the magnetic north and the stellar north is 7°36, that would mean a discrepancy of nearly one hundred feet at the base of the cliff â that is to say on the other rock face which forms the first spur of the Commander's Garret.