The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (18 page)

Easter Island script found on a message board. Not only is it written boustrophedon style, each line is upside down in relation to the previous one. The entire piece of wood would have to be turned through 180 degrees at the end of each line.

A way of writing that attempts to combine the advantages of both boustrophedonic and modern ways of writing has been found on Easter Island – perhaps the unlikeliest place on earth. In 1868 a German missionary called Zumbohm found there a set of

kohau rongo rongo

, or message boards, pieces of wood inscribed with what is probably an ideogrammatic script (like hieroglyphics). The remarkable thing about them is that they are written in a special kind of boustrophedon script in which each line is turned on its head in relation to the one before. This made it easy to continue writing from the place where you had to stop, while at the same time ensuring that all words were written in the same direction. The disadvantage, of course, was that at the end of each line the whole plank had to be turned around, which cannot have been terribly convenient.

Unfortunately, when Zumbohm made his discovery there was no longer anyone living who could read the script, so the meaning of what is written on those little planks of wood remains a mystery to this day. What the Easter Islanders did think they knew was where the script came from. According to traditional stories it was brought to them by their first king, Hotu-Matua, who arrived on the island by boat in the twelfth century. Whether or not this is true we cannot be certain, but striking similarities have been found between some of the symbols on the

kohau rongo rongo

and characters of the Indus script once used in parts of the Indian subcontinent.

The Chinese do things differently again. They write their characters in columns that run from top to bottom and are placed next to each other to be read from right to left, while each individual character is formed from left to right. But there have also been scripts that ran vertically downwards with columns arranged left to right, the ancient Mongolian script for example, or that were written as a vertical boustrophedon.

In truth there is no imaginable direction that has not been used by some linguistic group or other. Although people have been known to change the direction of their handwriting, think up an entirely different system, or adopt the style of their neighbours, until the sixteenth century no clear shift towards a particular direction of writing can be discerned. It seems a majority agreed early on that it’s more convenient to work from top to bottom than from bottom to top, but there’s no trace of a consensus when it comes to the horizontal direction, except that boustrophedon systems never really caught on. One extremely turbulent region in this respect is present-day Turkey, where the script was originally boustrophedon Hittite, after which people switched to writing Lydian, which ran from right to left, a language superseded by Greek, which is written in the opposite direction, before the Ottomans introduced the right–left Arabic script from 1453 onwards in which their Turkish language was written until 1928 when, under Atatürk, it was given a modern Latin alphabet of its own that ran from left to right once more.

However often and however categorically it is posited, the idea that writing from left to right is more natural seems to be primarily a product of Western imperialism and ethnocentrism: imperialism because many ways of writing have been pushed aside over the past five centuries by the relentless spread of Latin script across regions colonized by European powers; and ethnocentrism because the colonizers consistently saw native cultures as inferior and therefore felt their writing habits were unimportant.

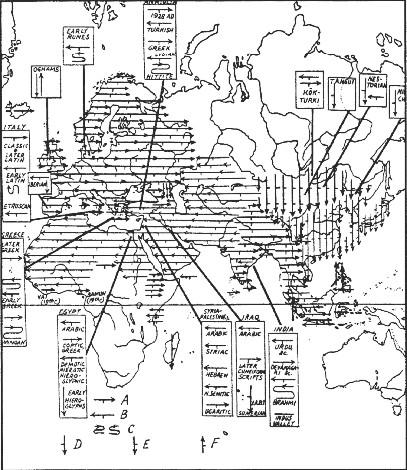

The distribution of writing directions in the Old World up until about 1500. The arrows give the direction in which the characters are written, either in lines or in columns. A short perpendicular line shows where the next line or column comes, so English is an arrow pointing right with a short stroke pointing downwards. A snaking line indicates boustrophedon. The boxed texts give the names of lost writing systems, or indicate developments in areas where the script changed repeatedly. In the latter case the most recent convention is at the top, the oldest at the bottom.

An example of cuneiform script. It means roughly: ‘May Ahoramazda preserve this land from the enemy, hunger and treachery.’ The vertical strokes present no problems, but the horizontal and diagonal strokes are almost impossible for a left-hander to produce. Cuneiform is the only exclusively right-handed system of writing.

Missionaries and evangelists in particular were responsible for propagating the Latin script and eroding local cultures. Today the economic dominance of the Western world ensures that its expansion continues, if rather more slowly. China, Japan and the Arab world do not seem likely to adopt the Latin alphabet, Cyrillic is in glowing good health and the Indonesian scripts and those of Southeast Asia are alive and well, yet Westerners still blithely pass over one inescapable fact: at least half the world’s population writes from right to left.

Since it’s impossible to point to a consistent preference either way and the vast majority of people everywhere are right-handed, we can safely conclude that there is no such thing as a natural writing direction. It’s not significantly harder to write from right to left with the right hand than the other way around, as the Arabs demonstrate. This also means it cannot be particularly difficult to write from left to right using the left hand. There are just a few practical problems that are perfectly easy to solve, with a bit of care and attention – but more of that later.

Nevertheless there is one system of writing that can be produced only with the right hand. It is cuneiform script, whose name derives from the Latin for wedge,

cuneus

, a reference to the shape of the horizontal and vertical strokes that are combined to form the characters. They were drawn in wet clay with a reed stylus that had a triangular profile, so each stroke acquired a small wedge-shaped notch at the start. Cuneiform script was written from left to right, with the notch marking the left end of each horizontal stroke. That is something which is almost impossible to achieve with the left hand.

22

The Weight of the Liver

It starts when we’re about two years old and it never stops. We ask ‘why?’ as soon as we come upon anything that strikes us as unfamiliar or strange. Left-handedness is one example. Virtually since the beginning of recorded time, people have asked themselves why some individuals prefer using the left hand to the right. The more astute among them have immediately realized that there are two questions here. The first and perhaps more intriguing is: why do we have a hand preference at all? Only after answering that question can we ask ourselves why not all of us favour the same hand.

The first person we know to have developed a theory about the cause of one-handedness was Plato. The debate in part seven of his

Laws

, between an Athenian and the Cretan Cleinias, shows that he thought we came into the world ambidextrous but started to favour one hand because of the empty-headed way mothers and carers treat children. This caused ‘lameness in one hand’. What precisely it was that had this pernicious influence he doesn’t tell us, unfortunately, which worked to the advantage of later adherents of similar theories, since it meant they could all the more easily hitch the world’s most ancient scientific authority to their wagons.

Even in Plato’s day the grass was greener on the other side of the fence. However superior the Greek philosopher may have felt to the many barbarian peoples of neighbouring lands, he was convinced that the upbringing of children was occasionally ordered better elsewhere – among the Scythians, for example, a much feared warrior people. Scythians, Plato has his Athenian say enviously, are far cleverer than Athenians. They use ingenious training methods to ensure the capacities of both hands and both arms are retained, proving that those who neglect their left side are acting contrary to nature.

To Plato one-handedness was merely a regrettable consequence of a careless upbringing. This cannot be the case, since there were never any truly ambidextrous Scythians and the frequency of right-handedness is roughly the same in all peoples. Aside from the minor impact of taboos, there’s hardly any difference between them, whereas we would expect significant variation if hand preference was a product of culture and upbringing.

Since Plato’s time only one really serious attempt has been made, by American psychoanalyst Abram Blau, to attribute left- and right-handedness entirely to environmental factors. He carried out his study during and shortly after the Second World War, in the days when behaviourism held the humanities in an iron grip. Before his day, all kinds of mechanistic explanations had come and gone over the centuries.

For as long as the Ancient World lasted, Plato and Aristotle retained their authority. Aristotle had little of interest to say about hand preference. He merely claimed that all movement came ‘by nature’ from the right and that the left hand was therefore unsuited to operating independently. After the collapse of the Roman Empire people had other things to do than to philosophize about hand preference, so it was the late fifteenth century before someone came up with a genuinely fresh insight.

That someone was Lodovico Richieri, an Italian who lived from 1469 to 1525. He was the first person, although by no means the last, to connect left-handedness with

situs inversus

, a condition in which the layout of the organs in the human body is reversed. Ricchieri, who was active some hundred years before William Harvey described the circulation of the blood, regarded the heart and liver as sources of heat. The heart served the left side of the body and the liver the right. If the liver was for some reason unable to perform its beneficial work to optimum effect, then a person became left-handed. One reason might be that their liver was on the wrong side, on the left.

It was not a particularly strong argument, and fortunately there is no connection between hand preference and

situs inversus

, a disorder with far-reaching consequences. We have been aware of this for centuries, as demonstrated by the work of the curious seventeenth-century Englishman Sir Thomas Browne, a prominent citizen of Norwich. Browne was a typical child of his time, whose studies at Oxford, Montpellier in France, Padua in Italy and Leiden in the Netherlands turned him into a liberally educated scholar in all kinds of fields. He was actually a physician by profession, but one no less at home in the experimental sciences of his time, not to mention alchemy, astrology and sorcery – a true

homo universalis

, who on one occasion even acted as an expert witness for the prosecution in a witch trial, which ended with both ladies convicted as charged.

Although he took seriously a great many things we would now regard as fanciful or based on old wives’ tales, his fame was derived mainly from his crusade against superstition. In 1648 he published a book with the wonderful title

Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or enquiries into Very Many Received Tenets and Commonly Presum’d

TRUTHS

, which examined prove but

VULGAR ERRORS

. Among the topics he covers in his book are the ideas of his time about left- and right-handedness, and he rightly rejects Ricchieri’s

situs inversus

theory on the grounds that the phenomenon is far too rare to account for something as common as left-handedness.

Situs inversus

occurs in only one in 10,000 people and even then it is often incomplete. Sometimes only the organs in the chest cavity are reversed, sometimes only those in the abdomen.

The idea that

situs inversus

had something to do with left-handedness proved astonishingly persistent. As late as 1862 Andrew Buchanan, professor of physiology in Glasgow, presented it as a cause, this time as part of a more general theory of equilibrium.

The liver, he said, is the largest and heaviest organ in our bodies. More of it lies to the right of our middles, so our centre of gravity is slightly to the right. To that extent his argument was correct. Generally speaking, the right half of the body is almost a pound heavier than the left. The theory that he went on to develop was less convincing. Buchanan believed that because of our displaced centre of gravity we suffer from an imbalance for which we compensate by leaning slightly to the left, using our left leg to stand on. This means that the right hand has greater freedom of movement, so people are generally right-handed. Buchanan could explain the existence of left-handed people only by assuming that their centre of gravity was slightly to the right, as a result of

situs inversus

.

You might imagine that such a theory could have been thought up only by someone who’d never seen a left-handed person from close proximity. It’s almost unbelievable that a well-trained physiologist of some repute could still think in 1862 that

situs inversus

was common enough to explain left-handedness, and no less strange that he seems not to have taken the trouble to test his theory, eccentric as it was, on the nearest available left-handed person. His ignorance seems all the more woeful given that almost a century earlier, in 1788, incontrovertible evidence had been produced that contradicted Buchanan’s assertion. In that year Scottish pathologist Matthew Baillie published in article in which he described a case of

situs inversus totalis

, or a complete reversal of the organs in the torso, devoting an entire passage to the fact that the man in question was right-handed. Despite the fact that the article was reprinted in the journal of the Royal Society of Physicians in 1809, people like Buchanan apparently knew nothing of it. Fortunately Buchanan was soon the target of fierce criticism from all sides – from other physiologists, for example, who had taken the trouble to probe the belly of a left-handed person, or listen to his heartbeat.

From time to time, right up until the end of the nineteenth century, variations on Ricchieri’s blood-supply theory kept popping up, often assigning a key role to the arteries under the collarbone, sometimes to other blood vessels. They were all based on an essentially identical assumption: in normal people, blood flows less easily to the left hand than it does to the right, whereas in left-handed people the opposite applies. When it eventually became clear that the causes of hand-preference lay in the brain rather than in the hands and arms, this assumption died a silent death.

One final death spasm was the idea that the blood supply to the left half of the brain was greater than that to the right, enabling the left cerebral hemisphere, which controls the right hand, to become more highly developed. That idea had its blood supply cut off in about 1900, when it became clear that differences in size between the two carotid arteries, each of which supplies blood to one half of the brain, did not consistently favour the left brain. Moreover, those differences were cancelled out alto gether by a system of cerebral arteries known as the Circle of Willis.

Mechanistic explanations of one form or another held their ground for four centuries, but in the end none of them came up to the mark.