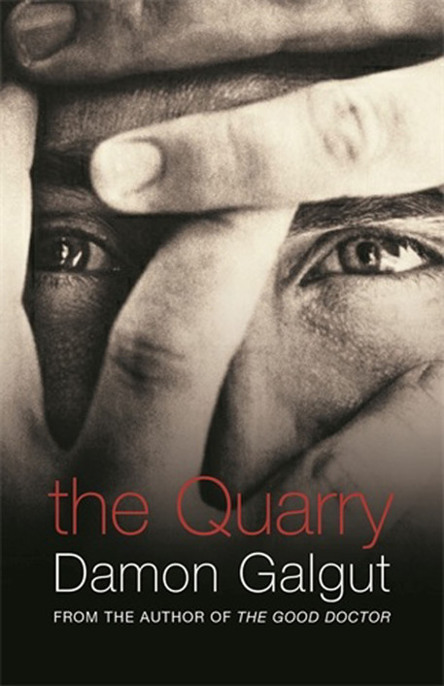

The Quarry

Authors: Damon Galgut

THE QUARRY

Damon Galgut was born in Pretoria in 1963 and now lives in Cape Town. He wrote his first novel,

A Sinless Season,

when he was seventeen. His other books include

Small

Circle of Beings, The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs

and, in 2003,

The Good Doctor,

which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the Commonwealth Writers Prize and the International

IMPAC Dublin Literary Award.

‘Damon Galgut is a true original.’

Geoff Dyer

‘A minor masterpiece.

The Quarry

is told in clear prose where every word counts and the plot and characters are utterly compelling… One of the best novels I

have read for some time.’

Ron Butlin,

Sunday Herald

‘Beautifully written.’

Aida Edemariam,

Guardian

‘A well-sustained work of semi-fantastical tension.’

Claire Allfree,

Metro

‘The scenes of township, quarry and shorescape have a strange, Beckett-like glow and menace.’

Adam Piette,

Scotland on Sunday

‘Not a word out of place… Fascinating.’

Vincent Banville,

Irish Examiner

‘The Quarry

has the same dry, feral quality as Damon Galgut’s best-known novel,

The Good Doctor

… The issues of guilt, injustice and redemption give

the novel a biblical feel. The writing shines in its peripheral vision, in the backdrops and corners of its scenes.’

Susan Salter Reynolds,

Los Angeles Times

‘A minimalist, almost allegorical story… Its tension is almost unbearable.’

Reba Leiding,

Library Journal

First published in 1995 by Penguin Books South Africa (Pty) Ltd.

Revised edition published in hardback in Great Britain in 2004 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published by Atlantic Books in 2005.

Copyright © Damon Galgut 1995, 2004

The moral right of Damon Galgut to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

1 84354 295 1

eISBN 978 0 85789 174 7

Printed in Great Britain by Bookmarque, Croydon

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

This book was completed

with the financial support of

the Foundation for the Creative Arts.

Thanks also to

Wendy Searle and Robert Hill

for their help.

Then he came out of the grass at the side of the road and stood without moving. He rocked very gently on his heels. There were blisters on his feet that had come from walking

and blisters in his mouth that had come from nothing, except his silence perhaps, and bristles like glass on his chin.

He crossed to a stone that was next to the road and sat. He was there for a while until, apparently without emotion, he bowed his head and wept into his hands. Then he stopped. He looked around.

The road was a curve of dust. On either side of it the grasslands stretched flatly away and there wasn’t a solitary tree.

‘Jesus H. Christ,’ said the man.

He took from his right hip pocket a glass cooldrink bottle which he had filled with brackish water at a stream. He unscrewed the top, spat into the dirt and took a long swallow. He checked the

level of the water and screwed the top back on. He put the bottle back into his pocket.

He sat for a while and looked. He stared at the lines on his palm. He started to say something. But it was too hot to speak. He said nothing. He shook his head once briefly, perhaps to shake a

fly from his face.

Then he stood and began to move again, tottering down that empty white trail. He looked like a figure fired in a kiln, still smoking slightly and charred. A gull followed him for a while,

hovering above his head, white and mewling. He stopped and threw a stone at it and it veered away to one side, tilting on its wings. It vanished over the grass, going towards the sea.

The road curved left. It went up a rise and then he himself could see the water, flat and endless as it moved in on the shore. He wanted to go to it. There was a bed of brittle reeds between the

road and the beach and he moved between the dry, crackling stalks. He came to the sand, which was white and fine, marked as though with music by the lines of ancient tides. Shells and weed,

skeletons of crabs.

He hung his clothes as he undressed on a piece of salt-whitened driftwood that stuck up out of the sand. His clothing was a peculiar mixture of articles. The boots looked military and so did the

socks. His shirt was red cotton with irregular white buttons and had been pilfered in passing from some nameless settlement somewhere. The blue pants were likewise stolen from a washing-line near

the city. He took them off and then he was naked in the cold wash of sun. His body was bizarrely quilted in areas of sunburn and whiteness, cleanness and dirt. He was a harlequin.

He went down to the water. There were gulls eddying above him again. He ignored them. He waded out a little way till the water reached his knees. It was cold.

He washed himself. There was a quality to his movements that was perfunctory and detached so that all activity was one. Crying or washing, it was the same to him. He scooped handfuls of the

freezing water over his back, his face. He scoured his skin with sand. Then he waited for a time with his hands at his sides and gazed at the thin shell of the horizon which seemed inscribed in ink

and which curved across all he could see of the world.

He went back to the beach. His clothes were where he’d left them, hanging on the piece of driftwood, and for a few moments he looked at these pieces of cloth with surprise. He had no

memory of leaving them there and it seemed to him for a moment that they belonged to someone else. Then he remembered. He dressed again slowly, the material sticking to the damp places on his skin.

The clothes smelled of something or someone or maybe of nothing.

He walked back through the reeds to the road. He went on walking north towards what he didn’t know.

In the late afternoon he came on another figure like him that was moving in the other direction, south. As they drew opposite each other on that empty road they stopped. Now that he stood near

another human form it could be seen that he was a big man, very tall. The other man was black, wearing a dark blue suit. They looked at each other warily.

He decided to speak.

‘Hello,’ he said.

The other man nodded, carefully.

‘Where does this road go?’ he said.

The other man smiled, inscrutably.

‘Do you know where I can find water?’

He took the bottle from his pocket to show him.

At this the other became voluble. He was pointing back the way he’d come. He spoke while he did, but in a language the first man didn’t understand. It was high-pitched and rapid.

Then he fell silent again and stood still. They looked at each other.

‘Goodbye,’ he said.

The other man nodded and smiled. ‘Goodbye,’ he said, pronouncing the word laboriously.

They went on their way. They drew slowly away from each other on the pale white road, casting backward glances at each other, like two tiny weights on a surface connected to each other by

intricate pulleys and dependent on one another for their continuing motion. Then the black man disappeared around a bend. The road went on, unwinding.

Towards evening he saw a tiny settlement of huts in the distance. Perhaps the other man had come from here. They were a way off to the left, at the sea, and he went down from the road and walked

towards them. They were fisherman’s cottages with walls painted white and he could see boats pulled up on the sand. There were children playing in the gravel outside the houses and they

stopped and looked at him with dull amazement as he advanced on them out of nowhere. A yellow dog barked at him and another took up the sound and it was in a cacophony of barks and howls that he

came into that place and stood at the edge of it, swaying slightly.

Later some men offered him food and for a short while he parleyed with them, crouched on his heels next to a fire, his shadow cast behind him in stuttering, pantomimic elongation along the

ground. A wind was coming up and the clouds that were rising earlier were heavy now and lit from within by jarring concussions of light. They shared their fish with him and he ate with his fingers.

They offered him beer but he drank water instead from an oily creek at the edge of the cluster of houses. They didn’t ask him his business, where he came from or to where he was going. He

spoke little to them. They were curious people, roughened by sun and wind, and their faces were seamed and unknowable under their tight woollen caps. They offered him a bed for the night but he

declined politely and set off again into the dark, leaning now into the wind with a tall and plum-coloured sky revealed in explosions of light.

It started to rain soon after. He walked for a while in the silver sheets of water with wind punching him like a fist, but soon came to a culvert under the road. There was water running through

it but he found a dry place inside and curled up with a gratitude that he had never felt for any other bed. He slept with a tiredness that was close to death. The storm passed and the clouds went

on, passing over the sea. Some night animal invisible except for the scarlet fissures of its eyes came to the mouth of the culvert and stared at him and went on. He slept on, beyond the memory of

dreams, and didn’t even twitch in his sleep.

When he woke it was still dark and he came crawling out of the culvert and stretched at the side of the road. The sky was vast and dark and taut and carried in it the myriad points and tracks of

stars. He drank water again from a pool at the mouth of the culvert and then set off at that same relentless pace with the sky beginning to whiten on his right. He passed what might have been a

farmhouse in the distance with a single light, itself a star, burning in one window and the slow and torpid shapes of labourers bestirring themselves outside. Then the sun, which is also a star,

came up as it perhaps always will and the light and heat of it grew across the earth tremendously.

It was good, then, to be walking amid grass that was coloured like roses and air that was soft on the skin. The ground was no longer entirely flat and hillocks rose subtly around him. He passed

a tree but it disappeared behind him and no other took its place.

Then the sun was climbing and the air lost its softness and there was no shade. He was going more slowly now than yesterday and there was a roughness to his joints that made it difficult to

move. He tried to whistle but no tune came to him and his mouth was too dry, so he stopped. His thoughts were weightless now, unfettered to his life. A small animal of some kind, a mongoose

perhaps, squirted softly across the road ahead of him and disappeared into the grass and he didn’t stop. There were distant high calls from birds and termite hills rose here and there like

citadels that might once have ruled the world and he went on as though to stop would be to cease altogether.

When he heard the sound ahead, he did not hesitate but went into the grass on the right and closed the yellow sheaves behind him like a curtain. He crouched there on the earth that was hard but

warm like the living flesh of some basking reptile and looked out through a gap in the stalks at a small patch of road perhaps ten metres wide and listened to the noise of the engine get closer and

louder till it filled and passed through that empty space before him that arena as small and charged as the stage of a theatre and had a vision brief but potent of a blue

bakkie

in the front

of which sat a florid farmer in short sleeves and hat and next to him his fat dour-faced wife and in the back on two metal drums a labourer lying in bone-breaking repose all three of them rendered

in perfect profile as though by the brush of a manic painter who was visionary and occasionally brilliant but almost certainly mad. Then the car was gone and there was dust and the grass was

shaking. He saw no reason to proceed but slid sideways to the ground and made himself comfortable and was almost instantly asleep as though expunged by some external dispassionate force that erased

his mind like a chalk sketch on a blackboard. He dreamed this time but of things long ago that he didn’t know he remembered.