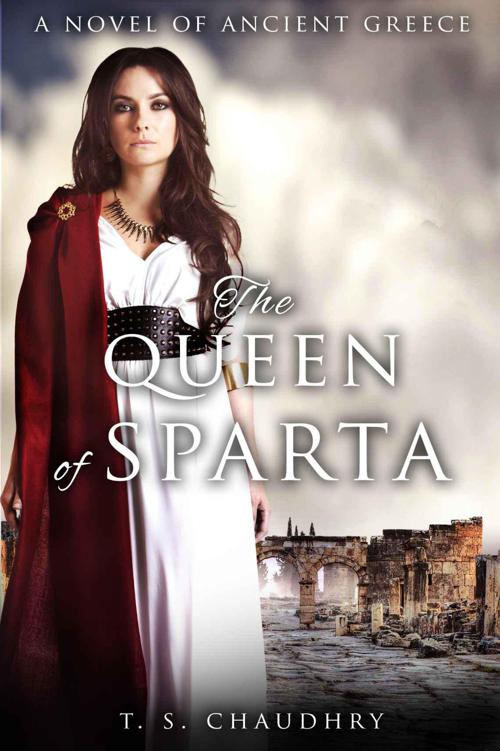

The Queen of Sparta

Read The Queen of Sparta Online

Authors: T. S. Chaudhry

THE QUEEN OF SPARTA

“My task is to relate the stories that have been told; I do not necessarily have to believe in them.”

Herodotus (‘the Father of History’)

By T. S. Chaudhry

Copyright © T. S. Chaudhry 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of T.S. Chaudhry, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. The author’s moral rights have been asserted.

ISBN: 978-0-9912661-0-4

Editing by Claire Wingfield

Designed and typeset by

Couper Street Type Co.

PROLOGUE

THE MANUSCRIPT

Aornos, Swat Valley

Lands of the Indus

Summer 327

BC

The forbidding stronghold, perched high on a peak, blazed against the cloudy night sky like a beacon. Down below, the old woman stood before her enemy, clasped in chains. Her gown was torn and tattered, her braided grey hair drenched in blood, her ferocious stare fixed on the man who had slaughtered her people and taken her land.

Alexander of Macedon had crossed over the high mountain range seeking the land the Persians called

Puraparaseanna

, ‘beyond the mountains,’ and what others described as the fabled lands of the Indus. He had thought that crossing into ‘India’ would be relatively easy, and indeed it had been, until he entered this valley. Here, everything had gone wrong. Alexander’s men, who had won great victories for hundreds of miles across Asia, were now facing adversaries they could not easily conquer. This new enemy could appear out of nowhere to strike hard and fast, and then disappear without a trace.

There was something peculiar about this enemy. Unlike most Asiatic foes Alexander’s force had faced before, these warriors fought with skill and discipline. A mere hundred of the enemy could hold off tens of thousands of Alexander’s men in narrow defiles, on bridges over fast-flowing rivers, and in the thick pine forests. And their horsemen were the most proficient Alexander had seen, carrying out remarkable manoeuvres in mountainous terrain, so unsuited for cavalry. These were no highland brigands, no mere hill-tribesmen – but fierce warriors equal to, or perhaps better than, Alexander’s conquering troops.

And then there was the valley. Its lush green hills awash with pine, oak, ash and cypress trees, dwarfed by magnificent snow-capped mountains; the varying shades of green flora contrasting with the grey-blue of the rivers flowing below. The effect was mesmerizing. Alexander’s men called it

Paradeisos

– ‘Paradise on earth’.

But the Macedonian conqueror had turned this paradise into hell. Where Alexander could not win by force, he resorted to guile, deceit and treachery. He made truces only to break them, attacking his enemies in their homesteads and settlements without mercy; destroying everything in his path. A quest for conquest had turned into a war of extermination. The resistance became only fiercer and the struggles more terrible. Still, one by one they fell, the fortified towns of Massaga, Ora and Barzius – and relentless slaughter followed. This last stronghold, rocky Aornos, had been the worst. It would have certainly been a defeat for the Macedonian king were it not for a mercenary commander, fighting for the enemy, who had opened the fortress gates for him.

Now, down below, hundreds of prisoners were gathered in front of the Macedonian camp. Wretched prisoners in tattered clothing huddled together by the banks of the fast-flowing Indus as rain began to fall.

Flanked by his commanders and advisors, Alexander was seated in front of these hundreds of prisoners on a field-chair. For all his fame, there was something was odd about the Macedonian conqueror. Short of height and slight of built, with golden curly hair, his face was smooth and soft; almost feminine. One of his eyes was blue and the other brown – which many regarded as a sign that he was touched by the gods, or was indeed a god himself.

Alexander gazed at the old woman who had led the resistance against him. In spite of her injuries, the woman stood erect, defiance blazing in her eyes. Though the hue of her skin was dark, her facial features were unmistakably European. The Macedonian King recalled the first time he had seen her, several weeks earlier, outside the walls of Massaga. When he sent out an emissary ordering her troops to lay down their arms, she had shouted back in Greek:

Molon Labe

– ‘come and get them.’

“Name?” he asked, in a rather harsh, almost squeaky, voice.

“Cleophis,” she replied, unflinching.

“Your name is Greek. Where are you from?”

She replied in a language Alexander could not understand. He turned to his Asiatic interpreters, who shrugged their shoulders.

A Corinthian officer came forward and whispered in Alexander’s ear. “‘This is my home. Perhaps you are the one who is lost, Macedonian?’”

Alexander frowned. “What is she speaking?”

“A dialect of Doric Greek, Your Majesty,” explained the Corinthian. “I have heard it spoken in Sparta, but only by royalty.”

“Damned Spartans,” muttered Alexander to himself. Of all the Greeks, they were the only ones who had refused to join his empire-building expedition. “What is a Spartan woman doing here, by the banks of the Indus?” Alexander asked, motioning the Corinthian to translate.

“I was born here, not in Sparta,” Cleophis replied, “though the royal blood of Sparta flows strong in my veins.”

“Ah …” Alexander smiled, “A descendant of Leonidas, no doubt?”

Cleophis remained silent.

“Woman, do you know I have destroyed Persia against whom the Three Hundred Spartans made their stand at Thermopylae, a century and a half ago?”

The old woman scowled. “It was the Greeks who fought the Persians then, not the Macedonians. Your ancestors served the Persians and later betrayed them. Your kind prefers treachery to courage.”

Alexander flew into a rage. “I am Greek. My fore-fathers came from Argos. My ancestor, Alexander the First, son of Amyntas, helped the Greeks defeat the Persians. It was he and Leonidas of Sparta and Themistocles the Athenian who saved Greece from the Persian yoke. By destroying the Persians’ Empire, I have only finished the work they began.”

Cleophis, in spite of her iron restraints, moved forward from the crowd of prisoners. “What makes you think any of

them

saved Greece? You men think you are the centre of the universe, don’t you? No, Macedonian, Greece was not saved by these men. She was saved by a woman.”

“This hag is mad!” said Alexander to himself. He got up in disgust.

As he rose to leave, Cleophis railed at him, “Macedonian, you conquer for the sake of conquest. Your lust for power knows no bounds. You can take this land but you will not be able to hold it. Mark my words, your presence here is only ephemeral, but the children of the Sakas will be drinking from the waters of the Indus for thousands of years to come.”

Alexander surveyed the prisoners. The people of Aornos, in chains and in torn clothes; sobbing women and children among them. All standing in mud, their homes burning in the background. He looked at Cleophis one last time. Her angry expression had grown even fiercer. The Macedonian king turned and calmly gave the order to his troops as he walked to his tent.

By morning, all were dead.

The next day, Alexander rode with a cavalry escort to the nearby town of Min-angora. Though only mid-afternoon, it seemed like dusk. Dark clouds had descended over the valley, shrouding it in darkness. Violent thunder echoed as drizzle turned to heavy downpour. The shadowy figures of the Macedonian horsemen, faces obscured beneath hooded cloaks, crossed a wooden bridge, and followed a road that ran alongside a fast-flowing river. Ahead was the town. A large wooden palace stood on a gentle hill on the left bank of the river. As the horsemen approached the palace, they saw a small dark figure walking – or rather, hobbling – towards them. He smiled and bowed low.

Alexander snapped his finger. The only native rider in his Macedonian retinue dismounted his horse and hurried to the King’s side. “Ask him if he is the one I must thank for delivering Aornos to me,” ordered the King.

But before the native could frame his question, the small man replied in heavily accented Greek. “Indeed, Majesty, it was I who arranged it. I am pleased to have been of service to you.”

The Macedonian king frowned. He could not understand why so many people, so far from Greece, could speak the language so fluently.

“My name is Vishnugupta Chanakiya,” the man continued. “But you may call me

Kautilya

… ‘the Crafty One’. The mercenary commander who betrayed Aornos to you is a compatriot of mine.”

Kautilya was a small bald man with deformed limbs. He had an unusually large hooked nose, bulging eyes, and his mouth revealed large misshapen, twisted teeth when he smiled. Still, his appearance was not without charisma.

Alexander nodded to one of his men, who rode out towards Kautilya and offered him a heavy purse. To the Macedonian king’s surprise, Kautilya waved it away, shaking his head.

“Your Majesty’s presence here is more important to me than gold,” explained Kautilya. “You are the enemy of our enemies and thus our friend. King Ambhi of Taxila awaits your aid against his rival, King Porus of the Puravas, overlord of the Suraseni. And if you defeat Porus, all of India will fall at your feet.”

Finally, someone had said something that pleased Alexander. He smiled and dismounted his horse.

“Has King … ah … Omphis … sent you, then? Is he the one you serve?”

“No, Majesty,” said Kautilya. “I serve no master. I am an exile from a kingdom further to the east. King Ambhi has given me asylum. He allows me to use the university in Taxila for research, in return for my political advice. I have asked him to ally with you.” Kautilya escorted him inside the modest wooden palace. “Rest now, Majesty. We shall talk later tonight.”

That evening, Alexander dined alone with Kautilya on the spacious terrace on the top floor of the palace. It was a pleasant place overlooking the river, furnished with beautifully carved wooden furniture, luxurious cushions and rich rugs. Jasmine vines hung over the wooden railing emitting the sweetest of fragrances, the rushing sound of the river’s water was almost melodic, and the distant lights of the town danced in the wind.

Alexander reclined on a comfortable bed-like couch, while Kautiliya squatted, cross-legged, on the carpeted floor in front of him. A low table full of tiny bowls was placed between them. He asked the Indian who were these people who had resisted him so fiercely. “And why are there so many people in this land who speak Greek?”

Kautilya explained, “Cleophis’ ancestors settled here centuries ago. They once ruled over the lands spanned by the river Indus. But their dominion eventually broke up as they fought both their neighbours and each other. One by one, their petty kingdoms and republics fell to others. You have just destroyed their last remaining state – and thus helped rid us of a major enemy.”

“And the Greek connections,” the Indian continued, “have been here for a while as well. Ambhi, the ruler of Taxila, also claims to be of Greek descent and even looks it. Taxila, like Min-angora, is virtually a Greek city, populated by Greek-speakers. People of Greek descent have been living here for well over a century. Some are said to be descended from Greek merchants who operated between here and the Asiatic Greek colonies of Aeolia and Ionia. Some say their ancestors were transplanted from the West and resettled here by Persian kings as punishment for rebellion. Others claim descent from Greek mercenaries who fought in civil wars between Persian princes. But then there are those who claim even stronger links with Greece, like Cleophis. Her tribe was called the

Ashkayavana

– the ‘Horse Greeks’ – who were ruled by people of royal Spartan blood.”

“Is that so? What was that hag saying about a woman defeating the Persians?”

Kautilya smiled. “Majesty, I have in my possession a manuscript, written … well, partly written … by a prince from Sakala who traveled to Greece a hundred and fifty or so years ago. He is one of the two authors of the manuscript. I have no doubt that the other is the woman Cleophis spoke of.”

Alexander asked what language the manuscript was written in.

“Greek,” replied Kautilya, “for reasons you will understand when you read the text.” He disappeared through the door of the balcony. Moments later he hobbled back, bearing a sheaf of parchments neatly strung together. Kautilya bowed low and handed the thick collection of parchments over to Alexander, across the low table. “I shall look forward to hearing your views on this manuscript, Majesty. But for now, I wish you good night.” Kautilya bowed once more and left the company of the Macedonian king.