The Queen's Cipher (52 page)

Read The Queen's Cipher Online

Authors: David Taylor

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #History & Criticism, #Movements & Periods, #Shakespeare, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Thrillers & Suspense, #Historical, #Criticism & Theory, #World Literature, #British, #Thrillers

In response to his inquiry about old filing systems she gave him a whispered lecture. Did he know that Leibniz was the founder of library science, responsible not only for modern indexing but for what libraries came to look like. Was he aware that a domed building symbolized the universal nature of knowledge and that Oxford’s Radcliffe Camera was based on Wolfenbuttel’s library design? He knew none of these things.

“That’s most interesting,” Freddie said tactfully, “but I was wondering how Duke August arranged his books.”

The librarian warmed to the question. The Augusteer Collection consisted of nineteen different categories covering every known university discipline plus a miscellaneous category called

Quodlibetica

which had its own card index. He liked the sound of that.

Flicking through the cards he reached the letter C. Would a Bacon treatise be filed as a codex, a concord or a confession? There was no mention of a codex and the other two were spelled differently in German and would come under E and K. But he had more luck with the letter D. Here he found

Das Schach-oder Konig-Spiel

, Chess or the King’s Game, a book written by Gustavus Selenus. The pseudonym Duke August had adopted in authoring his cipher manual!

To retrieve the volume a young assistant had to scale an incredibly long ladder and, at first glance, the book didn’t seem worth her effort. It was a fairly mundane German translation of the chess classic written by the Spanish monk Ruy Lopez.

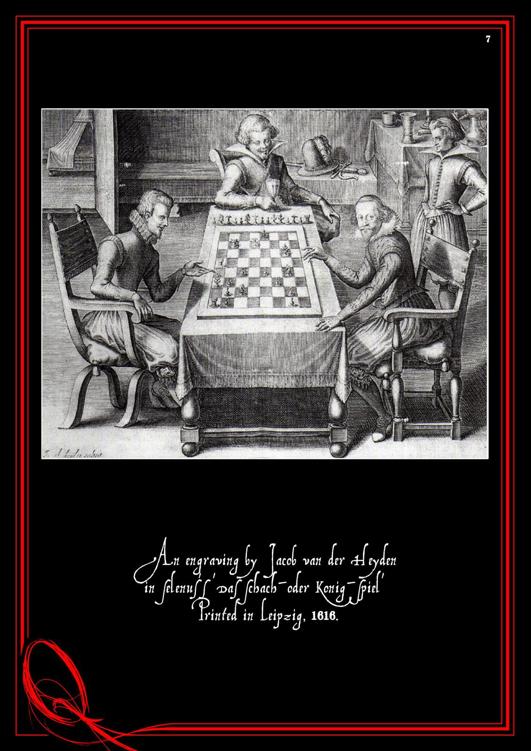

And then he saw it. An engraving of a contemporary game of chess in which two well-dressed players were sitting on opposite sides of a refectory table with a chess board between them while, at the far end of the table, a third figure watched their game, wine glass in hand. Like the players, the avuncular spectator wore breeches and a stiff linen-lined doublet and was the spitting image of Duke August.

Alarm bells rang in Freddie’s head but he couldn’t think why at first. Then his brain caught up with his instinct and he rushed out of the library without a word.

Heike Mittler was in the middle of a staff meeting when Freddie burst into her office waving a book in the air. “I’m awfully sorry to barge in on you like this but can I visit your storeroom?”

It was a bizarre request and he could see she was losing patience with him.

“I’m pretty sure I k-know where the Bacon codex is,” he stammered.

“Oh, really, and where would that be?”

“It’s in the gaming box on the refectory table.”

The Assistant Director gave him a long, hard look as if deciding how to classify him. L for lunatic seemed a front runner.

“Let me see if I’ve got this straight, Dr Brett,” she said, unable to keep the irony out of her voice. “You are seriously suggesting that Duke August hid a tract belonging to Lord Bacon in a gaming box that’s in our cellar. And how did this revelation come to you, may I ask?”

Freddie went red. He knew she was mocking him. “Through this book,” he replied.

The senior librarian sighed, took a bunch of keys out of a desk drawer and led the way to the storeroom. Unlocking the door and switching on an overhead light, she turned to him for further guidance.

He showed her the engraving in the chess book. “The trestle table over there is just like the one in the picture. They both have baluster legs and low circumferential stretchers. And look at this Venetian gaming box. It could have come out of the Embriachi workshop.”

The box was of ebony with inlaid walnut and rosewood squares and its side panels featured raised figures carved out of bone and horn. Heike Mittler’s tapered fingers explored a carved panel in the gaming box’s embossed surface.

“There’s something here,” she said softly. “It feels like a catch or a hinge.”

The box opened with an audible click to reveal a velvet-lined drawer in which checkers and dice were stored alongside a set of incredibly slender bone chess pieces with stacked floral crowns.

Freddie held a black knight up to the light and saw how its glossy stem was surmounted by a flat stylized horse. “These are very collectible. They are called the Selenus Set. There’s an illustration of the design in this book. I’m no expert but an original set must be worth at least ten thousand euros.”

Heike Mittler’s face glowed with pleasure as she contemplated this unexpected windfall. “What a find and we’ve got you to thank for it, Dr Brett. But I’m afraid there’s no codex in this drawer.”

“No, that would warrant a separate compartment.” He stared at the box, deep in thought, pushing and prodding each of its raised side panels before coming to a conclusion. “With your permission, Frau Mittler, I’d like to set up the pieces for a game. Perhaps you will play black.”

“But I don’t play chess.”

“Don’t worry, I’ll show you what to do.”

He arranged the pieces on the board and made the opening move. “In chess notation the squares are given letters, ‘a’ to ‘h’, left to right on the board. I’ve begun pawn to e4 and I want you to reply pawn to e5. I play knight to f3. Black mirrors the move by going knight to c6.”

“Why are we doing this?” she wanted to know.

“Oh, I’m playing Ruy Lopez’s famous opening. It’s featured in August’s book. The next move is the crucial one. It defines the game. Let’s see if anything happens.”

He moved his bishop to b5 and waited, more in hope than expectation. The room fell silent. Outside he could hear the distant rumble of thunder. But now there was a new noise, a scraping sound within the box. A drawer sprang out.

Freddie could hardly bear to look.

The compartment was empty apart from a scruffy piece of parchment that might have been used as lining paper. He took it out of the box and as he did so there was a loud gasp from the librarian.

“There’s some writing on the reverse side,” she told him.

It was an alphanumeric cipher. 13c5Kb813a6Ka82c6.

He tried to appear unruffled. “This is a stepping stone. The mixed cipher will tell us what to do next. That’s if we can work it out.” How he wished Sam was here. She was the cipher expert, not him.

“I best get started.” He took a biro and a notepad out of his jacket pocket and began the laborious business of converting numbers into letters.

Watching him work, she couldn’t control her curiosity. “Why did a picture in a book make you think the codex was in this gaming box?”

Freddie put down his ballpoint, grateful for the distraction. “How familiar are you with the theory of association.” He explained the theory’s key principles were similarity, contiguity and contrast. On studying the engraving he had been struck by the similarity between the refectory table it depicted and the one in the library storeroom. Add to this the proximity of an onlooker who resembled Duke August and the contrast between the illustrated chess board and the gaming box downstairs.

That had set him thinking. Early gaming boxes provided playing surfaces for a variety of pastimes – chess, draughts, backgammon and nine men’s morris – and came with at least one drawer for the storage of pieces. However, some Venetian craftsmen had gone a stage further by adding mechanically operated concealed drawers as secret hiding places.

“I’ve seen one of these portable safes in the Ashmolean Museum,” he told her. “I also knew about Duke August’s love of symbols. The emblematic title page to his

Cryptomenytices

is a perfect example. Artists used emblems as visual shorthand in those days. Have you seen the Hatfield portrait of Queen Elizabeth in which her dress is embroidered with eyes and ears to signify vigilance? Well, chess has its own iconography. The game represents a battle of wits and the chess engraving in Selenus’ book is signed by a Flemish artist called Jacob van der Heyden who did a lot of work for the secret society to which August belonged. Van der Heyden specialized in Rosicrucian emblems like the seven-layered rose with the cross-shaped stem and he also painted Frederick Duke of Wurrtemberg to whom the first Rosicrucian manifesto was dedicated.”

The librarian was struggling to keep up. “I still don’t understand why Duke August would hide Bacon’s book in this box.”

“All right, let’s talk about your duke. As a young man August travels widely, sets up a European-wide network of agents to purchase books, is a prime mover in the Rosicrucian uprising in Germany and later succeeds to the dukedom of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel, inheriting its library in the process. But there’s a major problem. Its 1635 and there’s a war going on. Wolfenbuttel is garrisoned by imperial troops. Although he can’t get into his palace, August is allowed to take possession of his library, moving his book collection there in barrels. But he’s not prepared to entrust his late friend’s highly sensitive treatise to a barrel or, indeed, to carry it on his person. Far better, he thinks, to smuggle Bacon’s codex into the building by hiding it in his Venetian gaming box. That’s my theory. Do you think I’m absolutely mad?”

Heike Mittler thought about this for a moment. “There’s a kind of insane logic to it,” she admitted. “You seem to know more about the duke’s history than I do.”

“It’s just a trick. I remember everything I read. It’s called an eidetic memory.”

“You have total recall?” she looked at him in wide-eyed amazement.

But his mind was elsewhere. “Surely it’s not that simple. The thirteenth letter in the alphabet used to be N and N is the notation for a knight in chess. K could stand for the king while the second letter in the alphabet is B for bishop. Of course! This is the classic endgame in which a knight and a bishop mate the king in three moves. Let’s see what happens when we play it out on this board.”

Freddie’s hand snaked out. Two knight moves forced the king to a8 before the bishop administered the coup de grace by moving to c6. There was a loud rasping noise and another concealed container appeared. He hooked his fingers into a groove beneath the drawer and pulled. It slid out half way, emitting a faint musty smell. Four hundred years of controversy would soon be resolved.

But there was nothing there.

No, he was wrong.

At the very back of the partition, in what seemed to be a recess, his fingers brushed against something that was rough to the touch. He forced the drawer out further to get a better look.

It was a sheet of coarse paper on which one word had been written in brown ink.

Schachmatt

. Checkmate in German!

He stood over the drawer, frozen in disbelief. It was as if his body had turned to stone. He had come to Germany on what Simon had rightly called a fool’s errant and, against all the odds, he had found what he imagined to be the treatise’s secret hiding place, yet all he had to show for it was this mocking reference.

He felt the librarian’s hand on his sleeve. “I am terribly sorry,” she whispered. “Someone seems to have beaten you to it.”

“It would appear so,” he said in a flat voice, trying to conceal his emotions. “Has anyone been down here recently? Working in the map room perhaps?”

“Only the CCTV engineer,” she replied.

“And when was that?” He was sure he knew the answer.

“He’s only just left – seemed in a hurry to get the rewiring done, worked through the night on it.”

“Had you placed an order for the work?”

“Funny you should ask that. I knew nothing about a new video surveillance system but he had a letter authorizing the work signed by the Director who, as you know, is in Greece and out of touch with us. I suggested he should wait until Professor Kaufmann’s return but he said he’d like to get on with the job and wouldn’t submit an invoice until Kaufmann had approved of what he’d done.”

“Was he a well-built chap in blue overalls who spoke German with an accent?”

“That’s the man,” Heike Mittler agreed. “He told me he was well satisfied with his night’s work.”

“I bet he was,” Freddie replied grimly. “Even so, I would have your closed circuit system checked. I doubt if he’s a qualified electrician.”

12 JULY 2014

Bathed in a soft late afternoon light the high-speed train hurtled through the Tuscan countryside. Out of the carriage window he watched the secret life of Italy flashing before his eyes: fields of yellow sunflowers and the silver green leaves of the olive trees; rows of Chianti vines with their luscious grapes ripening on dry-stone terraces; earthenware pots of red geraniums outside stone cottages on a hilltop village.

Freddie felt a hand on his shoulder. It was the ticket inspector. He pulled out his earphones and silenced Vivaldi on his MP3 player, thankful that he’d remembered to stamp his ticket on the station platform in Rome. Once it had been examined, he slumped back in his seat and closed his eyes, lulled by the gentle motion of the train and the susurration of Italian vowels as his fellow passengers discussed how unlucky the Azzurri had been in the World Cup. Unlike these patriotic football fans, he was experiencing a renewed sense of hope.

Twenty four hours ago his mood had been very different. Leaving the library in a daze, he had wandered aimlessly among half-timbered houses, blind to his surroundings, until he nearly stumbled into a canal dug by Dutch immigrants in the sixteenth century. Unlike most cities in Saxony, Wolfenbuttel had come through the Second World War unscathed and the timeless quality of its old town was enhanced by the absence of traffic in Lange Herzogstrasse and its side streets. Life went on much as it had done for centuries. Food was transported in carts; the postman delivered his mail on foot. Walking on, Freddie found himself in a typically Germanic market square where the central attraction was a bronze statue of Duke August leading his horse. From here cobbled alleyways beckoned left and right with signs indicating cafés and beer cellars. He chose one of the latter and set about drowning his sorrows in the bottom of a pilsner stein.