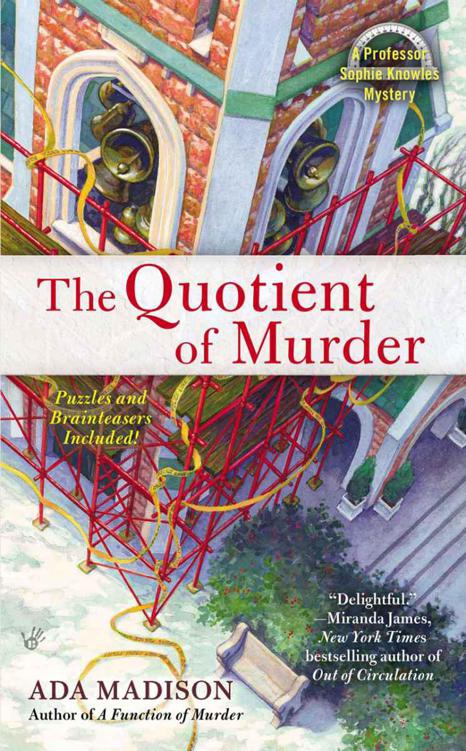

The Quotient of Murder (Professor Sophie Knowles)

Read The Quotient of Murder (Professor Sophie Knowles) Online

Authors: Ada Madison

Praise for

“Madison, as she did in this book’s two predecessors, fashions an intelligent puzzle for the reader . . . Give her high marks for another winning whodunit.”

—

Richmond Times-Dispatch

“A Function of Murder

is an enjoyable addition to the Sophie Knowles cozy mystery series.”

—

Curling Up by the Fire

“[An] enjoyable academic amateur sleuth filled with puzzlers, brainteasers, and mathematician quotations . . . Fans will appreciate Sophie’s inquiry as she adds the clues and subtracts the red herrings to try to extrapolate the identity of the killer before she becomes a cold statistic.”

—

Genre Go Round Reviews

“Sophie is an interesting amateur sleuth . . . Logic puzzlers will enjoy the tidbits included in the text and the brainteasers at the end of the book.”

—

The Mystery Reader

“Math professor Sophie Knowles makes an auspicious debut in Ada Madison’s delightful

The Square Root of Murder

. Petty academic politics and faculty secrets prove fertile topics in Madison’s very capable hands.”

—Miranda James,

New York Times

bestselling author

of

Out of Circulation

“A clever puzzle,

The Square Root of Murder

is well plotted, and the reader will want to see more of Sophie. Madison has found the right equation for success in this entertaining series debut.”

—

Richmond Times-Dispatch

“I strongly recommend

The Square Root of Murder

. It offers readers the familiarity of a cozy mystery with some interesting new twists. Five stars out of five.”

—Examiner.com

Berkley Prime Crime titles by Ada Madison

THE SQUARE ROOT OF MURDER

THE PROBABILITY OF MURDER

A FUNCTION OF MURDER

THE QUOTIENT OF MURDER

THE QUOTIENT OF

Ada Madison

THE BERKLEY PUBLISHING GROUP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

A Berkley Prime Crime Book / published by arrangement with the author Copyright © 2013 by Camille Minichino.

Math, puzzles, and games by Camille Minichino.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Berkley Prime Crime Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group.

BERKLEY

®

PRIME CRIME and the PRIME CRIME logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

For information, address: The Berkley Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Group (USA) LLC,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

ISBN: 978-1-10162661-0

Berkley Prime Crime mass-market edition / November 2013

Interior map by Dick Rufer.

Cover art by Lisa French.

Cover design by Lesley Worrell.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Thanks as always to my critique partners: Nannette Rundle Carroll, Jonnie Jacobs, Rita Lakin, Margaret Lucke, and Sue Stephenson. They are ideally knowledgeable, thorough, and supportive.

Thanks also to the extraordinary Inspector Chris Lux for continued advice on police procedure. Chris is always available to answer my questions—often the same one for every book—or to share a laugh. I’m so lucky to have met him.

Thanks to the many other writers and friends who offered critique, information, brainstorming, and inspiration; in particular: Gail and David Abbate, Sara Bly, Mary Donovan, Margaret Hamilton, Diana Orgain, Ann Parker, Suzanne Bilge Rasmussen, Jean Stokowski, Karen Streich, and Ellyn Wheeler.

My deepest gratitude goes to my husband, Dick Rufer. I can’t imagine working without his support. He’s my dedicated Webmaster (minichino.com), layout specialist, and on-call IT department.

Thanks to my very helpful editor, Robin Barletta, and the staff at Berkley Prime Crime.

Finally, my gratitude to my Primary Care Editor, Michelle Vega. Michelle is a bright light in my life, personally supportive as well as superb at seeing the whole picture without missing the tiniest detail. Thanks, Michelle!

PRAISE FOR BOOKS BY ADA MADISON

Don’t spoil my circles!

—ARCHIMEDES

Four seasons aren’t enough to please some New Englanders. The administrators of Henley College, in Henley, Massachusetts, gleefully wedged in a fifth this year—our first ever January Intersession. Four weeks of classes, three credits each, and thirty-one days of braving the winds on an icy-cold campus.

Brilliant.

“You know you love teaching, anytime, anywhere, Sophie,” more than one of my friends said every time I whined about the extra load.

“Yeah, yeah,” I admitted, acknowledging that I couldn’t get enough of class prep and student interaction.

But now, two weeks into the so-called term, a pipe somewhere in the nether regions burst, and the heating system went out in Benjamin Franklin Hall, home to the mathematics and science departments. After shivering through my nine o’clock calculus class, I carried my mug of coffee and laptop into the faculty lounge, hoping someone had started water boiling on the hot plate. During my free hour, I could give myself a steam facial and warm up at the same time.

I wasn’t the only one with that idea. I set my computer down and joined two other department chairpersons—the tall, heavily mustachioed Ted Morrell, from physics, and the much smaller, strawberry blond Judy Donohue, head of biology—standing at the side table, where the hot plate occupied a prime position. I squeezed between them.

“I can’t teach maxima and minima in a freezing classroom,” I complained to Ted, the most senior faculty member in Franklin Hall. “What good is having a physicist in the building if you can’t fix the plumbing?”

“I’m on it, Sophie.” Ted saluted and smiled. He spared me his standard speech about the difference between science and technology. According to Ted, physicists were busy trying to understand the universe; it was the engineers who were responsible for fixing its leaks.

It sounded like a cop-out to me.

No one wanted to argue with Ted, however, since he was our go-to guy for any computer problems in the building. In deference (or not) to his age, we called him our One-Hundred-Year-Old Geek, the techie who could unfreeze your bits and bytes or recover the file you thought you deleted.

Our laptops lined up on the conference table, the three of us engaged in a time-honored New England winter tradition, hovering over the steam from two pots of boiling water, talking and drinking our coffee in a half-bent position while the bubbles gurgled away. I hoped someone who needed boiling water for tea would join us so I’d feel less wasteful and environmentally unsound.

This morning we also eyed a pink pastry box next to the hot plate. It was the Chemistry Department’s turn to supply goodies today, and a chem major had delivered the box earlier. Ted patted his flat stomach, making a calculation before indulging, then went for a cruller. I followed his lead, promising myself an exercise routine soon, and broke off a small piece of cinnamon twist.

Judy sucked in her stomach, then let out a breath and admitted, “I pass, because I just walked by a hunky, very buff guy in the basement fixing our heater, and I might want to go back and introduce myself.”

Ted and I pretended not to get the connection.

To add to the January woes, parking on campus had become a nightmare. Large vehicles and heavy equipment for the renovating and reopening of our carillon facility had taken over the lots on the east and north sides of the Administration Building. Besides the bell tower, the landscaping at the back of Admin was also getting a makeover.

Franklin Hall had its own lot next to the tennis courts at the other end of campus, but the displaced cars had moved in on us. This was as good a time as any to gripe about it.

“Someone was in my spot today,” Judy said. “A dirty old blue Citroen.” She brushed the front of her spotless wool jacket, as if she’d inadvertently leaned on the scruffy vehicle.

“Probably someone from the French Department,” Ted joked, halfway through his cruller. “But where else are they going to park?”

“Anywhere but my spot,” Judy said, stomping her feet. For circulation or for emphasis? Probably both. “They could at least remove some of that equipment that they’re through with. I’ll bet they’re never going to use that backhoe again.”

“It’s all for a good cause,” I offered, and hummed a few notes of the Westminster Chimes. Thanks to a generous donation from a group of alumnae, Henley College’s Music Department would once again have a full program of carillon studies and regular concerts.

“Listen to Ms. Arrives-at-Dawn Knowles,” Ted said, flicking a crumb of powdered sugar from his mustache. “You still have your spot.”

“That would be

Dr.

Arrives-At-Dawn Knowles,” I teased. “But you have a point.”

Usual construction delays and a late December snow had slowed the carillon project, but the remaining work was fairly weatherproof, and we were promised a concert in the spring.

In spite of the inconvenience of the parking situation, most faculty and students were thrilled about the restoration and upgrading of our carillon. Comprising fifty-three (formerly forty-eight) bells, the instrument was housed in a tower attached to the sprawling English Gothic Administration Building. A system of wires and ropes linked the oversize keyboard, much bigger than those of a regular organ, to the bells’ clappers. It was hard to believe that the present construction zone, with ugly equipment, scaffolding, and black and yellow caution tape, would soon give way to beautiful music from the tower.

Judy shook the box of pastry for a better view of the bottom layer, then succumbed to a piece of Danish that had broken loose. “I know, tsk, tsk,” she said, as if someone had reprimanded her. “You’re being so good, Sophie.”

“Uh-huh.” I didn’t share my reasons for holding back—there were more goodies in my immediate future, and I wanted to save my appetite. I planned to share cake with my class after my eleven o’clock seminar, then enjoy lunch with my boyfriend, search-and-rescue hero Bruce Granville. Medevac pilots didn’t often get a regular lunch hour, so I’d jumped at the chance to meet Bruce downtown.

“We don’t have our parking lot back, but at least the excruciatingly dull special faculty meetings are over,” Judy said.

I nodded, recalling endless hours of meetings to decide details that should have taken five minutes each. Should we charge admission to climb the tower for a tour? (No.) For attendance at a carillon concert? (No.) Should the players be called carillonists or carillonneurs? (The former.) Whose names should be inscribed on the new bells to be installed? (Big donors, of course.) Which shade of gray should we use for the walls, “sea salt” or “samovar silver”? (Who even remembers the final decision?)

“Notice, no one in administration ever mentioned the real reason the carillon program was cancelled to begin with,” Judy said.

“Knock, knock, Doctors?”

Our longtime, diffident janitor, Woody, stood at the door, his smile broader than usual. He knew we’d be pleased to see the load he was ready to pull into the room—a gray metal cart with two shelves full of small space heaters.

Three variations of enthusiastic thanks, plus a round of applause, caused a light flush to appear over Woody’s face. We invited him to share the wealth of sugar in the pink box.

Woody scooped up a jelly donut and placed it to the side on a napkin. “For after I set these up,” he said, pointing to his cart. “Thank you, Doctors,” he added.

“Thank you, Mr. Conroy,” Judy said, but I was unsure whether he’d recognized her tease. We’d long ago stopped trying to coax him into using our first names.

Five minutes later, life-giving warmth radiated from the coils of a heater at the back of the room.

We moved from the hot plate and arranged chairs around the heater, while Woody cleared the way for a second unit at the front of the room.

Judy’s earlier comment came back to me. “What do you mean ‘the real reason’ for closing the tower?” I asked her. “I thought it was sealed off because of some building code violation and we didn’t have the money for retrofitting.”

Judy pointed to our colleague from physics. “Ted would know better, but what I heard was that twenty-five years ago, toward the end of the spring semester, a young woman jumped from the tower. A sophomore French major, right, Ted?”

Ted nodded, frowning, closing his eyes.

I drew in my breath. “A student jumped from our tower? That’s why the tower was sealed off?”

I looked at Ted for more information. He’d been at Henley forever, an icon in horn-rimmed spectacles. I’d lost track of how long ago we’d celebrated his thirtieth anniversary. But Ted wasn’t in a sharing mood today. He opened his laptop, finished with the tower conversation.

Even with the new source of heat in the room, I felt a chill. Maybe because of the horrible image now in my head. A girl falling from the tower, hitting concrete, breaking bones, bleeding . . .

I thought back. I’d been born and raised in Henley, but twenty-five years ago, I was a college student on the West Coast. Had I been so self-centered that I wouldn’t have paid attention to such dramatic news in my hometown? Granted, I was three thousand miles away and it occurred more than half my lifetime ago, and it made sense that my mother wouldn’t have wanted me to focus on it. Still . . .

I finally caught my breath. “How come you knew this and I didn’t?” I asked Judy.

Though Judy was five years my junior, we’d joined the faculty the same semester, fifteen years ago. She’d arrived straight out of grad school, skipping the phase I’d been through, where you try gainful employment in industry before giving in to your first love, teaching.

“I heard bits and pieces my first year here. I haven’t thought about it in a long time,” Judy said.

“They quit having all those live music concerts and we put in that electric system. Nobody was supposed to talk about it,” Woody said, packing up his toolbox.

“A very good idea,” Ted offered, without lifting his eyes from his keyboard.

“Yes, sir, Doctor,” Woody said, taking Ted’s message to heart, and, I guessed, wishing he’d never contributed to the conversation.

“The real answer to your question, Sophie, is that everyone knows you’re no fun when it comes to keeping gossip alive,” Judy said. “That’s why no one brought it up with you.”

I didn’t know whether to say “Sorry” or “Thanks.”

Ted gave Judy a disapproving look, and she quickly explained. “I didn’t mean that this was gossip. It must have been an unimaginable tragedy for her family, of course. For everyone at Henley.”

Judy had a way of being flip that annoyed Ted—the straightest arrow in the building—at least once a day in my experience, but we both knew she never meant disrespect.

The natural questions were swimming around in my head. Who was the girl? Why did she jump? How did her family handle it?

I didn’t have to ask. Judy tuned in to my vibes. “The girl was from an influential family in Boston.” She snapped her fingers, remembering. “Her father was a high-profile lawyer, if I recall correctly, and headed to Washington. The first rumors were that she was depressed over a boyfriend who’d just dumped her. But they never did verify that she was depressed or that there even was a boyfriend.”

“Maybe she was flunking her classes?” I offered, knowing how high the stakes were for some students.

Ted cleared his throat. “No one really knows why anyone does anything,” he said, in a sweeping pronouncement. “What does it matter, anyway?”

“I just found it strange that so many rumors persisted, even after the suicide ruling,” Judy said.

“You think the boyfriend was a cover story?” I asked. “There was another reason she jumped from the tower?”

Judy shrugged. “Anything is possible. There could have been more to it. Something embarrassing to the family. I’m pretty sure the girl’s father was running for office. Sometimes that alone is enough to doubt what you see in the press. The girl—”

“Kirsten Packard,” Ted interrupted. “The girl was Kirsten Packard, and her father was in the state’s attorney general’s office, running for election as US attorney, which he won. He served his country in that capacity, and died a few years ago.”

There was a finality to Ted’s tone. He might as well have said, “Zip it,” or, more suited to him, “Now can we please drop this topic?” But Judy, who never met a rumor she didn’t like, wasn’t finished.