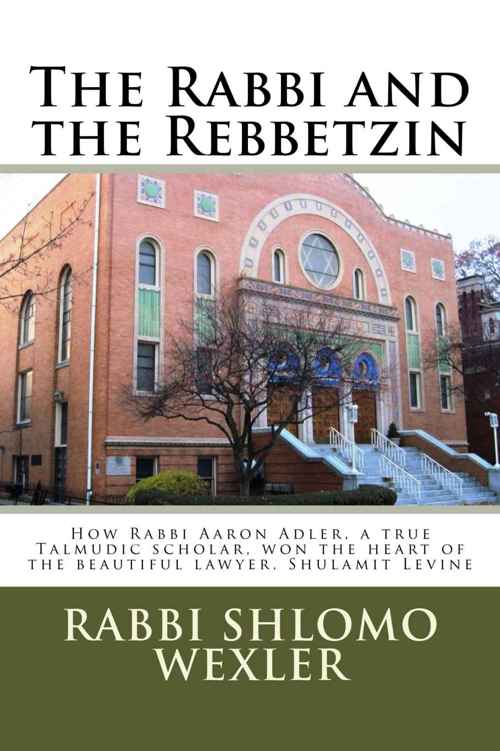

The Rabbi and The Rebbetzin

The

Rabbi and the Rebbetzin

How

Rabbi Aaron Adler, a true Talmudic scholar, won the heart of the beautiful

lawyer, Shulamit Levine

A novel

by

Rabbi

Shlomo (Stanley) Wexler

The

Rabbi and the Rebbetzin

Copyright

© 2013 Shlomo (Stanley) Wexler

All

rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the copyright owner, except in the

case of brief quotations in reviews and articles.

First

Edition.

Rabbi Shlomo Wexler

,

the author of this work, was a community rabbi for 30 years. During that time

he performed many marriages and provided guidance and counsel to couples who

were considering marriage. In addition to his religious training, Rabbi Wexler

was a professor of sociology who taught courses on marriage and family in

various colleges. The statistics that he learned showed that, in the opinion of

sociologists, marriage is more likely to be successful when the husband and

wife are brought up and socialized in similar cultures and subcultures.

Differences that contribute to a greater proportion of marital failures can

include variations in the ages of the couple, their social class, and their

educational background. Intermarriages between members of different religious

groups and interracial marriages also have a far lower success rate among

members of different racial and religious groups. Where it is not too late,

marriage counselors tend to steer young couples away from marriages of this

kind.

While this work is a fictional novel, it is based on true life experiences and

contact with many young couples in the rabbi’s experience. The story of the

couple involved in this book did not have a prognosis for a successful marriage.

Although they were both Jewish, there were gross dissimilarities between

husband and wife. There were vast differences in social class, education, and

worldly experience between the marriage partners. Character differences were

even sharper than the usual ones.

To understand how such huge differences can develop within the framework of a

single religion, one must realize that Judaism socializes people within a group

of active and heterogeneous subcultures. The subcultures within Judaism range

from an apathetic view of religion to extreme ultra-Orthodox patterns of

religious behavior. As far as religion is concerned, the different Jewish

subcultures include: Strict Orthodox, ultra-Orthodox, Modern Orthodox,

Conservative, and Reform groupings. When we speak of similarity in the

upbringing of marriage partners, we tend to think more of sub-cultural

differences.

Rabbi Aaron Adler

studied in a

yeshiva which could definitely be classified as ultra-Orthodox. The institution

made only one concession to students who were planning careers in business or

in the rabbinate. The school allowed a limited number of secular credits

outside of regular studies in colleges not connected to the seminary. Strictly

enforced regulations allowed senior students to take only six credits each

semester at night and nine credits during summer vacation. While studying at

the seminary, Rabbi Adler accumulated a total of 85 credits and was short of

his BA degree by 35 credits. As a serious student, the rabbi was able to

acquire a good background in English, literature and philosophy.

In

his religious practice, the rabbi was very observant. He did not go on dates

and formed no connections to any women. He had virtually no interest in world

affairs, current events, or social experiences.

Shulamit Levine

can be classified

as a Modern Orthodox woman. She went out on dates, participated in mixed

events, led an active social life and, blessed with a fine voice, sang before

mixed audiences. She was brought up in a strictly Orthodox home, and in her

early years she studied at a local day school through high school. She was a

brilliant student and attended a state university with the goal of someday

entering a major law school. She was interested in current affairs and involved

in extra-curricular activities at her school.

The

men she dated were all Jewish, but many of them were not fully observant. This

was a cause of great concern to her parents, who were afraid that she might

marry outside of her faith or to someone who is Jewish but with no sense of

religion.

Abe Levine

,

Shulamit’s father, was a very successful businessman. He ran a well-known

computer company which maintained more than twenty-five branches on the eastern

seaboard of the USA. He lived a strict Jewish life, and maintained a fully

kosher home. At home, his children were fully observant. He was a

multi-millionaire, and his family lived a very luxurious life. Since Aaron

Adler lived on the border of poverty, the contrast in the economic status

between him and Shulamit was vast. Levine was active in his local synagogue,

and generously supported the local day school and the yeshiva where Aaron Adler

studied.

Chana Levine

,

Shulamit’s mother, was more religious than her husband and daughter. She had earned

a PhD degree and was an instructor in psychology at a local university. She

admired Rabbi Adler for his religious beliefs and practices, and was proud of

her daughter’s association with the rabbi.

In this particular story, the groom qualifies as ultra-Orthodox. His parents

were Holocaust survivors who provided their children with an ultra-Orthodox

education. The groom studied in right-wing yeshivos and continued his studies

until he was ordained as a rabbi. Although he was in his early twenties, he had

never associated with any women eligible for marriage. His training qualified

him only to be a rabbi or a teacher in some day-school or yeshiva.

In sharp contrast, the woman who became his rebbetzin was a brilliant student

and looked forward to working in law. She was the daughter of a

multi-millionaire who owned a hi-tech business and was active in Jewish causes,

and an officer in many religious institutions. He encouraged religious

practices of his children, but was not unduly strict about their religious

upbringing. After completing the day school, his daughter studied in a high

class college, and first met her husband-to-be when he came to their community

to serve as an interim rabbi for the holiday season. At school, she enjoyed an

active social life and was very popular among the male and female students at

the college.

Rabbi Wexler realized that none of his readers would anticipate a successful

courtship and romance between a bride and a groom who were so different from

each other. The author was aware of the inherent difficulties of such a match,

but he harbored an internal belief, namely, that if any bride and groom

practiced tolerance and had the support of their families, they could make such

a marriage work. While such varied attributes are rare, it does not mean that

failure of the marriage is inevitable. The author feels that these qualities

should be part of every union and can overcome differences that lead to failure

and dissolution of a marriage.

Yeshiva Ohr Moshe

assists Congregation Beth Israel of Dunberg

The clock on the bare, well-worn

wall was exactly one minute past 9 AM when Mrs. Fisher’s deep voice pierced the

silence of the executive director’s office. The yeshiva secretary announced, “Call

from Abe Levine on line two.”

After

a few preliminaries, Levine explained that he was facing a major problem. In

steadily rising tones that bordered on panic, he shouted, “You must help me.

You simply have to find someone in a hurry.”

Rabbi

Weiss was startled by the loudness of the voice. Abe Levine was as solid a

businessman as one could imagine. In all the years that he knew the man, Levine

impressed him as a person possessed of the ultimate in self-control. Face to

face, and even more so on the phone, he never got excited, never raised his

voice. The mild temperament persisted, despite being the owner and chief

executive of a multi-million dollar business, a computer supply mail-order

company.

“Take

it easy, Abe,” the rabbi pleaded. “The situation will not get any better by

yelling. Give me some more information, and the yeshiva will do its best to

help.”

Levine

was still agitated. He worked in a stressful business where a single mistake

could cost thousands of dollars. But business problems never fazed him. Now,

however, he was being confronted by a situation where he could not fall back on

years of experience and profound technical skills. He was in an area where he

had no resources with which to work and only limited knowledge of the subject

matter. He needed outside help desperately, and Rabbi Weiss was the only person

he could pressure into assisting him.

Levine,

as it happened, was president of a synagogue. While both his shul and his

business generated severe headaches, the business at least compensated him for

his pains to the tune of almost two million dollars a year. To the synagogue, from

which he received no money, he donated more than $20,000 annually. From his

contributions, he earned only the privilege of suffering communal woes, but

acquired a larger share of life in the World to Come.

Levine’s

shul, Congregation Beth Israel, was the smaller of the two synagogues in

Dunberg, PA, an upper income suburb in the Pittsburgh sphere of influence.

Temple Beth Moses, the larger of the two congregations was affiliated with the

Conservative Movement. Of the thousand Jewish families in the community, almost

half were affiliated with the Temple. Fewer than 200 families belonged to Beth

Israel which, depending on one’s point of view, could be classified either as

Traditional or Modern Orthodox. The synagogue could not afford a resident rabbi

during the year, and had to rely on invited clergy for holidays and special

occasions.

“Rabbi,”

Levine said, “we are in deep trouble. Here it is, ten days before Rosh Hashanah,

and I get a call from Rabbi Ilan Solomon at the Pittsburgh Academy this

morning. Solomon teaches there and has been our holiday rabbi for the last five

years. It seems that his mother in Israel became seriously ill and he has to

fly back home. He will certainly be away for Rosh Hashanah, and probably Yom

Kippur as well. At our shul, he conducted the services, delivered the sermons,

and chanted

Shachris

and

Minchah

. He also conducted the Torah

readings. I asked him if he knew anyone in the area who could replace him, and

he said there were only a few in the vicinity who could do it and they were all

booked a long time ago. He suggested that I call the yeshiva.”

Rabbi

Weiss quickly realized that he had a severe crisis on his hands. While securing

a holiday rabbi from the yeshiva would be an almost impossible task, the

consequences of not coming to Abe Levine’s assistance would be far worse. “What

about the cantor you have, Reverend Joseph Martin? Maybe he could also daven Shachris

and then you can get a volunteer to conduct the other services.”

“Rabbi,

you fail to sense the situation that exists in this shul. Shachris is important

but not critical. I could chant it myself if necessary, if the congregation

would overlook the fact that I am not a total Sabbath-observer. The rabbinic

services are far more important, because many of our members are only

marginally affiliated. Their children are always pushing them to switch to the

Conservative synagogue. If we don’t provide an acceptable rabbi for the

holidays, they will pull out of the shul.

“Listen,

I put too much effort into this shul to lose it over a thing like this. When I

visited your yeshiva two years ago, you told me that your students were being

trained to serve the Jewish community as rabbis and educators. I am a patron of

the yeshiva, and I get a lot of my friends, who don’t even know what a yeshiva

is, to donate large sums of money to the school. I can certainly expect some

assistance from you when I need it.”

Levine

may not have realized it, but not only was he a patron of Yeshiva Ohr Moshe (a

category reserved for those who contributed between $10,000 and $20,000 annually),

but he was actually the school’s largest single donor. Rabbi Weiss was keenly

aware of this fact of life, and had to tread cautiously.

“Listen

to me, Abe. This is the first notice I have of the problem. With God’s help, we

will come up with an answer. Rabbi Rosenberg, the dean, finishes his morning

lecture by 10 AM. We will get right to work on the matter. Where will you be

later this afternoon?”

“Right

here at Telacomp, until 6 PM. I’ll be waiting for your call.”

Rabbi

Weiss was a picture of despair when he got off the phone. Institutional executive

directors are expected to radiate cheerfulness when they deal with the faculty

and general public. It was hard for him to do so now with so much at stake. Ohr

Moshe was a small yeshiva, struggling for students, status and financing. To

attract qualified students to the yeshiva, the school had to offer generous

scholarships. While there were students available who could afford to pay the

full tuition, such students were generally mediocre and the yeshiva could

accept only a limited number of them. All told, tuition accounted for less than

a third of the school’s income. The rest was raised by solicitations from

individuals and foundations. Rabbi Weiss worked very hard at fund-raising and

managed to keep the yeshiva afloat. When he wasn’t out soliciting, he

administered yeshiva affairs, including registration, food supplies and

building maintenance.

The

rabbi remembered Abe Levine’s visit to the yeshiva with a touch of bitterness.

The dean had advised him one morning that Levine was coming to the school and

required a tour and the usual spiel. Rabbi Rosenberg was not American-born and

did not speak English well enough to do the public relations work. A son of Holocaust

survivors, he left Europe in his childhood and completed his rabbinical studies

in Israel. After migrating to America, he established a higher yeshiva in Pittsburgh,

where he served as the dean. His first step was to engage an executive director,

Rabbi Simcha Weiss, to raise funds, manage the business end of the school, and

deal with the community.

The

director was an American who studied in a New York yeshiva until he was

twenty-four. After receiving Semicha at the yeshiva, he left the school in

order to complete his college education. He then worked in various educational

positions for about ten years before he accepted the executive directorship at Rabbi

Rosenberg’s school, Yeshiva Ohr Moshe. He had never seen Levine before his

visit to Pittsburgh, although he had met Abe’s father on a number of occasions.

Judah, the father, had been a successful merchant in Pittsburgh and was fully

observant. Rabbi Rosenberg called upon the elder Levine a few times to

establish a level of annual support and then delegated the account to Rabbi

Weiss. The director visited the Levine store once a year, and always emerged

with $1,000 to $2,000.

Rabbi

Rosenberg quickly briefed the director on the upcoming visit. “Before Judah

Levine died last year, he instructed Abe to support the yeshiva generously. The

son studied in the local day school for a while but he knows very little about yeshivos.

He is a brilliant man, with a Ph.D. in electronic engineering from M.I.T.

Furthermore, he owns a huge mail order company that employs over a hundred

people. When you speak to him, emphasize the importance of the yeshiva and its

services to the Jewish community.”

Rabbi

Weiss was deeply troubled by the last sentence. He would follow his instructions

faithfully because he was being paid to do so. But his conscience bothered him

whenever he had to gild the lily in such a blatant manner. He did believe that yeshivos

were important and fulfilled many vital functions in Jewish life. Communal

service, however, was not one of them. Students who attended the yeshivos were

encouraged to distance themselves from the large synagogues and other Jewish

public institutions. They were expected to worship in small “Shtiblach,” whose

members were strictly observant and davened yeshiva style. Such shuls had no

official rabbis, no cantors, no sermons, and none of the trappings of the

larger American Orthodox congregations.

The

students who received ordination were not expected or qualified to serve as

pulpit rabbis. They lacked secular education and the life experience required

of a congregational rabbi. The Talmud and the Codes they studied at the yeshiva

prepared them only for intensive religious living. Even after marriage, yeshiva

students were expected to spend several additional years in religious studies.

When they finally went out into the world, a number of them became teachers in yeshivos

and day schools, while others drifted into business.

To

tell Abe Levine that Ohr Moshe was training the future leadership of American Orthodoxy

was a gross exaggeration at the very best, and Rabbi Weiss did so without

emphasis or real conviction. He was grateful that Levine did not pick up on the

point and ask him for statistics. He realized, though, that a man as bright as

Levine would remember such a remark and he greatly feared that someday his idle

words would come back to haunt him. Today, obviously, was the day of

retribution.

Aside

from a lingering sense of guilt, the visit was clearly a huge success. Abe

Levine was in a generous mood at the time and was quite flattered by all the

attention he received from the learned rabbis. Rabbi Weiss was able to persuade

him to dedicate a classroom in memory of his father and subscribe to an annual

patron membership.

At

the request of Rabbi Weiss, a special meeting was convened at 1:15 PM in the dean’s

office. It was the earliest time that the three faculty members could gather.

The class that the dean was giving when Levine called was a special lecture to

the entire student body on the laws of Rosh Hashanah. Since it was Monday, all

classes had their regular lectures from 10:45 AM to 12:30. In addition to Rabbi

Rosenberg, the faculty consisted of Rabbis Bernstein and Kurland. The latter

taught the intermediate class and also served as the Mashgiach (spiritual counselor)

to all the students. Rabbi Bernstein, who was still in his twenties, taught on

the preparatory level. The next lower two levels consisted of twenty students

each. Fifteen older students were considered advanced and were instructed by

the dean himself. Twelve of the students were designated as pre-rabbinic. This

meant that their studies were part of the two-year Semicha program at the

yeshiva.

Faculty

meetings were not unprecedented at Ohr Moshe. Although yeshivos are not

democratic institutions, each instructor, who carries the Hebrew title “Rosh Yeshiva,”

had the option of consulting faculty members individually or collectively. The

final decision on any course of action was always made by the dean himself.

Rabbi Rosenberg held group meetings because he valued the input of the faculty

and sensed that it was good for the morale of faculty members to feel that they

were part of the decision-making process. On many occasions, a consensus was

reached at such meetings and relieved the dean of making unilateral rulings.

Otherwise, the dean had to make difficult choices between opposing points of

view.

Rabbi

Weiss was expected to attend faculty meetings and did so whenever his other

duties permitted it. Issues raised at such meetings often impacted on the image

or finances of the yeshiva, and in those areas the director was the

acknowledged expert. He respected the scholarship of all the instructors, but

he did not get along with Rabbi Kurland. In his eyes, the Mashgiach was too

hard-driving and inflexible. Ohr Moshe was, after all, an out-of-town yeshiva

just getting established. The Mashgiach had studied and taught in one of the

larger East Coast schools, but left when some of his extreme views did not

prevail. Rabbi Weiss, who joined Ohr Moshe before Rabbi Kurland was hired,

tried to warn the dean that the man was an extremist. The dean, however, could

not resist the temptation of securing for his new school a teacher with a

well-established reputation.

Now

Rabbi Weiss was facing Rabbi Kurland across the conference table in the dean’s

office. Rabbi Rosenberg was in his usual seat at the head of the table, and

Rabbi Bernstein sat alongside the Mashgiach. Rabbi Weiss noted the condition of

the dean’s office with a degree of pride. The paint was fresh and the walls

carried pictures of famous rabbis neatly hung in elaborate frames. While his

own office remained shabby, the director made a special effort to keep the dean’s

office respectable. Ohr Moshe occupied a once-beautiful synagogue building in

the old Jewish section. As the Jews fled the changing neighborhood and moved to

the suburbs, the congregation became depopulated. The membership was reluctant

to sell the facility to a church, so they rejoiced when Ohr Moshe indicated a

willingness to take over the building. The main worship floor was remodeled to

hold a large study hall in the front half and classrooms and offices in the

back. The dean had an office and classroom on one side, and the Mashgiach had

his office and classroom on the other. There was also space for two additional

rooms in what was the women’s worship area in the balcony. The school kitchen,

dining room, and administrative offices were located on the ground floor of the

building.