The Race to Save the Lord God Bird

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

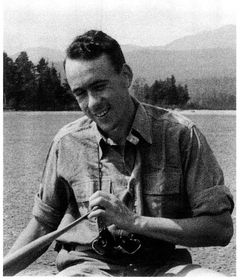

In memory of James Tanner;

and to the many biologists and conservationists to come

who will continue his work

by preserving species in their habitats

and to the many biologists and conservationists to come

who will continue his work

by preserving species in their habitats

James Tanner

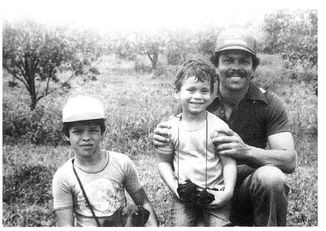

And to Giraldo Alayón,

who, like the Ivory-bill itself,

balances science and magic in Cuba

who, like the Ivory-bill itself,

balances science and magic in Cuba

Giraldo Alayón with

sons Giraldo (left)

and Julio, in 1987

sons Giraldo (left)

and Julio, in 1987

Table of Contents

A BIRD OF THE SIXTH WAVE

TO BECOME EXTINCT IS THE GREATEST TRAGEDY IN NATURE. EXTINCTION MEANS THAT ALL THE members of an entire species are dead; that an entire genetic family is gone, forever. Or, as ornithologist William Beebe put it, “When the last individual of a race of living things breathes no more, another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one can be again.”

Some might argue that this doesn't seem so tragic. After all, according to scientists, 99 percent of all species that have ever lived are now extinct. And there have already been at least five big waves of mass extinction, caused by everything from meteorites to drought. The fifth and most recent wave, which took place a mere 65 million years ago, destroyed the dinosaurs along with about two-thirds of all animal species alive at that time. In other words, we've been through this before.

But the sixth wave, the one that's happening now, is different. For the first time, a single

species,

Homo sapiens

âhumankindâis wiping out thousands of life forms by consuming and altering the earth's resources. Humans now use up more than half of the world's fresh water and nearly half of everything that's grown on land. The sixth wave isn't new; it started about twelve thousand years ago when humans began clearing land to plant food crops. But our impact upon the earth is accelerating so rapidly now that thousands of species are being lost every year. Each of these species belongs to a complicated web of energy and activity called an ecosystem. Together, these webs connect the smallest mites to the greatest trees.

species,

Homo sapiens

âhumankindâis wiping out thousands of life forms by consuming and altering the earth's resources. Humans now use up more than half of the world's fresh water and nearly half of everything that's grown on land. The sixth wave isn't new; it started about twelve thousand years ago when humans began clearing land to plant food crops. But our impact upon the earth is accelerating so rapidly now that thousands of species are being lost every year. Each of these species belongs to a complicated web of energy and activity called an ecosystem. Together, these webs connect the smallest mites to the greatest trees.

This is a story about a species of the sixth wave, a species that wasâand maybe still isâa bird of the deep forest. It took only a century for

Campephilus principalis,

more commonly known as the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, to slip from a flourishing life in the sunlit forest canopy to a marginal existence in the shadow of extinction. Many species declined during that same century, but the Ivory-bill became the singular object of a tug-of-war between those who destroyed and sold its habitat and a new breed of scientists and conservationists dedicated to preserving species by saving habitat. In some ways, the Ivory-bill was the first modern endangered species, in that some of the techniques used today to try to save imperiled plants and animals were pioneered in the race to rescue this magnificent bird.

Campephilus principalis,

more commonly known as the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, to slip from a flourishing life in the sunlit forest canopy to a marginal existence in the shadow of extinction. Many species declined during that same century, but the Ivory-bill became the singular object of a tug-of-war between those who destroyed and sold its habitat and a new breed of scientists and conservationists dedicated to preserving species by saving habitat. In some ways, the Ivory-bill was the first modern endangered species, in that some of the techniques used today to try to save imperiled plants and animals were pioneered in the race to rescue this magnificent bird.

I say the Ivory-bill “maybe still is” a bird of the deep forest because some observers, including some very good scientists, believe that a few Ivory-bills continue to exist. Since I first became interested in birds in 1975, I have read or heard dozens of reports that someone has just caught a fresh glimpse or heard the unmistakable call of the Ivory-bill. Again and again, even the slimmest of rumors sends hopeful bird-watchers lunging for their boots, smearing

mosquito repellent onto their arms, and bolting out the door to look for it. Year after year they return with soggy boots, bug-bitten arms, and no evidence.

mosquito repellent onto their arms, and bolting out the door to look for it. Year after year they return with soggy boots, bug-bitten arms, and no evidence.

The Ivory-bill is a hard bird to give up on. It was one of the most impressive creatures ever seen in the United States. Those who wrote about itâfrom John James Audubon to Theodore Rooseveltâwere astonished by its beauty and strength. They gave it names like “Lord God bird” and “Good God bird.” Fortunately, in 1935, when there were just a few left, four scientists from Cornell University took a journey deep into a vast, primitive swamp and came back with a sound recording of the phantom's voice and twelve seconds of film that showed the great bird in motion. It was a gift from, and for, the ages.

Cornell's image sparked a last-ditch effort led by the Audubon Society to save the Ivory-bill in its wilderness home before it was too late. But others were equally intent on clearing and selling the trees before the conservationists could rescue the species.

The race to save the Ivory-bill became an early round in what is now a worldwide struggle to save endangered species. Humans challenged the Ivory-bill to adapt very quickly to rapidly shifting circumstances, but as events unfolded, the humans who tried to rescue the bird had to change rapidly, too. The Ivory-bill's sagaâperhaps unfinishedâcontinues to give us a chance to learn and adapt. As we consider the native plants and animals around us, we can remind ourselves of the race to save the Lord God bird and ask, “What can we do to protect them in their native habitats while they're still here with us?”

THE HOSTAGE

A majestic and formidable species ⦠has eye is brilliant and daring, and his whole frame so admirably adapted for his mode of life and method of procuring subsistence, as to impress on the mind of the examiner the most reverential ideas of the Creator.

âAlexander Wilson, writing about the Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Wilmington, North CarolinaâFebruary 1809

A

LEXANDER WILSON CLUCKED HIS HORSE SLOWLY ALONG THE MARGIN OF A SWAMP IN North Carolina. Bending forward in the saddle, he squinted out at the small birds that flitted across the moss-bearded boughs of giant cypress trees, hoping he could get a clear shot without going into the water. When he heard the first call of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, he knew what it was instantly, even though he had never seen one before. Here was the toot of a toy horn everyone had told him to expect, repeated again and again. Then came the two-note

ba-DAM,

a crack of bone against wood that shot through the swamp. When you hear that, everyone had said, then you'll know you're really in the South.

LEXANDER WILSON CLUCKED HIS HORSE SLOWLY ALONG THE MARGIN OF A SWAMP IN North Carolina. Bending forward in the saddle, he squinted out at the small birds that flitted across the moss-bearded boughs of giant cypress trees, hoping he could get a clear shot without going into the water. When he heard the first call of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, he knew what it was instantly, even though he had never seen one before. Here was the toot of a toy horn everyone had told him to expect, repeated again and again. Then came the two-note

ba-DAM,

a crack of bone against wood that shot through the swamp. When you hear that, everyone had said, then you'll know you're really in the South.

Wilson's heart must have been racing as he dismounted and crept toward the bird, said to be as big as a rooster, with bold black-and-white plumage and an outsized bill that gleamed in the sun like polished ivory. The power of this bird was legendary. A century before, the British explorer Mark Catesby had stood beneath a tree and watched in awe as an Ivory-bill, digging for insects, ripped away huge sheets of bark, sending down a bushel basket's worth of wood in less than an hour. Even President

Thomas Jefferson had written about “the white-bill woodpecker.” Here was a meeting Wilson had long anticipated.

Thomas Jefferson had written about “the white-bill woodpecker.” Here was a meeting Wilson had long anticipated.

He moved slowly, for he was a walking powder keg. Wilson kept a loaded pistol in each pocket, a loaded rifle strapped across his shoulder, a pound of gunpowder in a flask, and five pounds of gunpowder on his belt. This was not only for the robbers, panthers, and bears or any hostile Indians he might encounter in his travels. Gunpowder was a tool of his trade, like paint. Wilson was on a mission to paint and describe every single bird species in the new United States of America. Once he was finished, he would compile the portraits and accounts into a set of volumes and sell them. He believed there were enough people who wanted to know about the birds of the new nation to provide him a living. For now, he was asking them to buy subscriptions to his work, to pay him in advance and have faith that he would finish the paintings and mail off the booksâin other words, to invest in

him.

Though he was hardly rich, Wilson was off to a good start, having sold subscriptions to President Jefferson and most members of his cabinet.

him.

Though he was hardly rich, Wilson was off to a good start, having sold subscriptions to President Jefferson and most members of his cabinet.

Wilson preferred to sketch live birds if he could trap them, but usually he couldn't. So he shot them out of trees and shrubs and marshes, firing off a hailstorm of small steel pellets that struck the birds in a deadly mist. He hoped that no single ball would tear their feathers too badly or mangle their features beyond recognition. He also hoped they wouldn't be disfigured when they fell and struck the ground. He collected the carcasses and skinned them, removing their internal organs so they wouldn't rot, then packed them in salt and stuffed them full of cotton until his journey was over and he would have time to paint them.

When Wilson finally got a clear look at the Ivory-bill, he steadied his shotgun, aimed carefully, and killed the bird cleanly. He fetched it from the base of the tree and placed it in his collection bag. Hours later he brought down another Ivory-bill, and was probably still smiling about his good luck when he came upon yet a third peeling bark from the high branches of an enormous cypress tree. The big male's red crest glowed like a flame in the sunlight.

Again Wilson fired, sending another trophy to the ground. When Wilson got to it, this bird was still moving, having been wounded only slightly in one wing. Delighted, Wilson flung his coat over the woodpecker to calm it down and carried it slowly back

to his horse. As he planted his foot in the stirrup and swung his leg over the saddle, the bird exploded into life with a shriek resembling “the violent crying of a young child.” The horse bolted for the swamp. Wilson seized the reins with one hand and tried to keep hold of the bird with the other, finally calming at least the horse. “It nearly cost me my life,” he later wrote.

to his horse. As he planted his foot in the stirrup and swung his leg over the saddle, the bird exploded into life with a shriek resembling “the violent crying of a young child.” The horse bolted for the swamp. Wilson seized the reins with one hand and tried to keep hold of the bird with the other, finally calming at least the horse. “It nearly cost me my life,” he later wrote.

ALEXANDER WILSON

“His eyes were piercing, dark and luminous and his nose looked like a beak,” wrote Charles Leslie of his hero Alexander Wilson. Leslie started working for Wilson at the age of seventeen, coloring in the sketches of American birds that Wilson had drawn. “I remember the extreme accuracy of his drawings,” wrote Leslie, “and how carefully he had counted the number of scales on the tiny legs and feet of his subjects.”

Born in Scotland, Wilson became known as the “Father of Ornithology” in the United States after the publication of his nine-volume work American Ornithology. Wilson spent many years traveling on horseback throughout the eastern United States, collecting specimens and painting birds at a time when many of the continent's birds were unknown. He carefully and sometimes beautifully described the range, habitat, and behavior of our birds. A petrel, a plover, a warbler, and even a whole genus of warblers still bear Wilson's name.

The bird shrieked all the way into the town of Wilmington, twelve miles down the road. As the strange trioâfrazzled naturalist, bulging-eyed horse, and wailing woodpeckerâcareened through the streets of Wilmington, startled townspeople rushed to their doors and windows, their faces filled with concern.

Reaching a hotel, Wilson tied his horse and took the bird inside. It was still wailing under his coat as the landlord and curious guests clustered around. Wilson asked for a room for himself and “my baby,” and then, to satisfy the curious, he lifted the

coat from he bird. When the laughter died down, he took the Ivory-bill to his room and left it here, locking the door behind him. Then he went back outside to tend to his horse.

coat from he bird. When the laughter died down, he took the Ivory-bill to his room and left it here, locking the door behind him. Then he went back outside to tend to his horse.

A few minutes later, he turned the key to his door again and pushed it open. The air was thick with dust. Chunks of plaster covered his bed. Anchored to a window frame, near the ceiling, the woodpecker was smashing away at the wall with sideways strokes of its mighty bill. Already it had torn a fifteen-inch-square crater in the wall, and it was, just seconds away from piercing through to the outside and making its escape.

As Wilson lunged for it, the bird snapped its beak and slashed back with dagger-sharp claws. Wilson finally managed to loop a string over one leg. Pulling the bird down, Wilson fastened it to a table and went outside again to catch his breath and try to find some food for the woodpecker. Wilson realized the creature must be starving, but he probably had no idea what he could find in Wilmington that an Ivory-billed Woodpecker would eat. This time, when Wilson returned, he opened the door of his hotel room and found the bird perched atop a pile of mahogany chipsâthe ruins of the hotel's table. The bird puffed up its feathers, swung its head around, and glared at Wilson through a furious yellow eye.

That was enough. Wilson grabbed his sketchboard and began to draw while he still had a room. Whenever he edged too close to the bird, he paid a price in blood. He wrote of the Ivory-bill: “While [I drew him] he cut me severely in several places and, on the whole, displayed such a noble and unconquerable spirit, that I was frequently tempted to restore him to his native woods. He lived with me nearly three days, but refused all sustenance, and I witnessed his death with regret.”

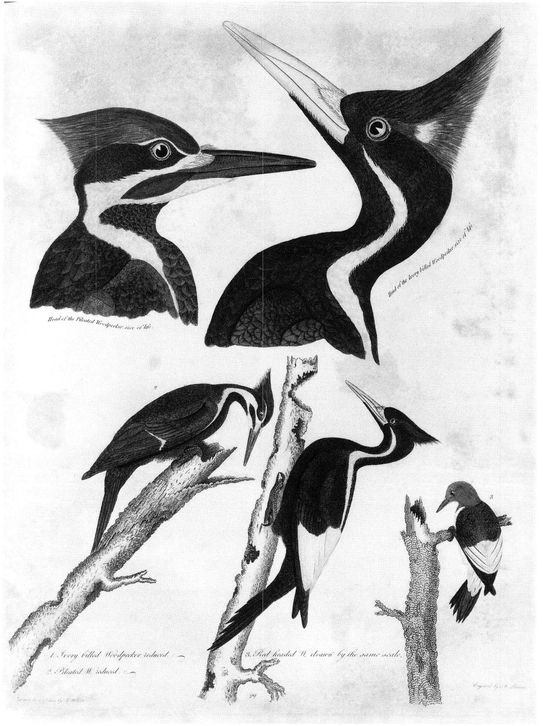

Wilson's Ivory-bill (

upper right and lower middle

) shares the page in his

American Ornithology

with two Pileated Woodpeckers and a Red-headed Woodpecker (

lower right

)

upper right and lower middle

) shares the page in his

American Ornithology

with two Pileated Woodpeckers and a Red-headed Woodpecker (

lower right

)

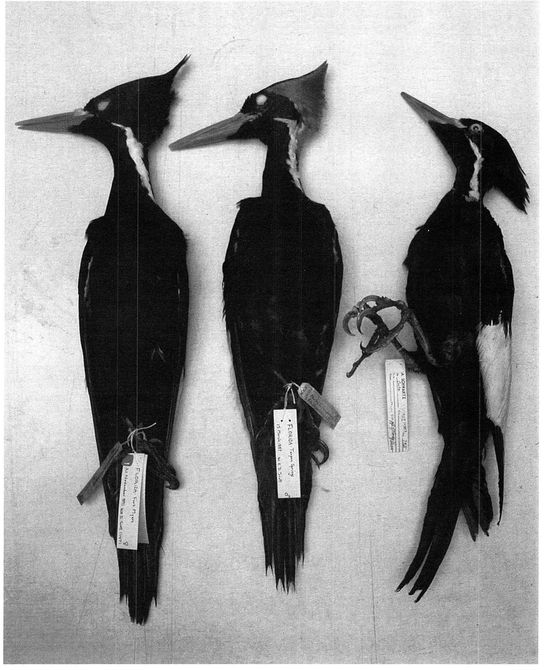

Ivory-billed Woodpecker specimens at the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science

Other books

Quiet Neighbors by Catriona McPherson

Matters of the Blood by Maria Lima

The Sunset Witness by Hayes, Gayle

The Seeker A Novel (R. B. Chesterton) by R. B. Chesterton

Death Devil's Bridge by Robin Paige

The Recognitions by William Gaddis

Ahriman: Hand of Dust by John French

The Attempt (The Martian Manifesto Book 1) by Bob Lee

The Lost Abbot by Susanna Gregory