The Rational Optimist (40 page)

Read The Rational Optimist Online

Authors: Matt Ridley

Besides, there is just no sign of most renewables getting cheaper. The cost of wind power has been stuck at three times the cost of coal power for many years. To get a toehold in the electricity market at all, wind power requires a regressive transfer from ordinary working people to rent-seeking rich landowners and businesses: as a rule of thumb, a wind turbine generates more value in subsidy than it does in electricity. Even in 6,000-turbine Denmark, not a single emission has been saved because intermittent wind requires fossil-fuel back-up (Denmark’s wind power is exported to Sweden and Norway, which can turn their hydro plants back on quickly when the Danish wind drops). Meanwhile a Spanish study confirms that wind power subsidies destroy jobs: for each worker who moves from conventional electricity generation to renewable electricity generation, ‘two jobs at a similar rate of pay must be forgone elsewhere in the economy, otherwise the funds to pay for the excess costs of renewable generation cannot be provided.’ Although green campaigners are wont to argue that raising the cost of energy is a good thing, by definition it destroys jobs by reducing investment in other sectors. ‘The suggestion that we can lift ourselves out of the economic doldrums by spending lavishly on exceptionally expensive new sources of energy is absurd,’ writes Peter Huber.

But that’s today. Tomorrow, there may well be carbon-free energy sources that do not have these disadvantages. It is possible, though unlikely, that these will include hot, dry geothermal power, offshore wind, wave and tide, or even ocean thermal energy conversion, using the temperature difference between the deep sea and the surface. They may include better biofuels from algal lagoons, though personally I would rather see a nuclear power plant so the lagoons can be used for fish farming or nature reserves. It is also possible that quite soon engineers will be able to use sunlight to make hydrogen directly from water with ruthenium dye as a catalyst – replicating photosynthesis, in effect. Clean-coal, with its carbon dioxide reinjected into the rocks, may play a part if its cost can be brought down (a mighty big ‘if’).

A big contribution will surely come from solar power, the least land-hungry of the renewables. Once solar panels can be mass-produced at $200 per square metre and with an efficiency of 12 per cent, they could generate the equivalent of a barrel of oil for about $30. Then, instead of drilling for $40 oil, everybody will be rushing to cover their roofs, and large parts of Algeria and Arizona with cheap solar panels. Most of Arizona gets about six kilowatt-hours of sunlight per square metre per day so, assuming 12 per cent efficiency, it would take about one-third of Arizona to supply Americans with all their energy: a lot of land, but not unimaginable. Apart from cost, solar’s big problem, like wind’s, is its intermittent nature: it does not work at night, for instance.

But the obvious way to go low-carbon is nuclear. Nuclear power plants already produce more power from a smaller footprint, with fewer fatal accidents and less pollution than any other energy technology. The waste they produce is not an insoluble issue. It is tiny in volume (a Coke can per person per lifetime), easily stored and unlike every other toxin gets safer with time – its radioactivity falls to one-billionth of the starting level in two centuries. These advantages are growing all the time. Better kinds of nuclear power will include small, disposable, limited-life nuclear batteries for powering individual towns for limited periods and fast-breeder, pebble-bed, inherent-safe atomic reactors capable of extracting 99 per cent of uranium’s energy, instead of 1 per cent as at present, and generating even smaller quantities of short-lived waste while doing so. Modern nuclear reactors are already as different from the inherently unstable, uncontained Chernobyl ones as a jetliner is from a biplane. Perhaps one day fusion will contribute, too, but do not hold your breath.

The Italian engineer Cesare Marchetti once drew a graph of human energy use over the past 150 years as it migrated from wood to coal to oil to gas. In each case, the ratio of carbon atoms to hydrogen atoms fell, from ten in wood to one in coal to a half in oil to a quarter in methane. In 1800 carbon atoms did 90 per cent of combustion, but by 1935 it was 50:50 carbon and hydrogen, and by 2100, 90 per cent of combustion may come from hydrogen – made with nuclear electricity, most probably. Jesse Ausubel predicts that ‘if the energy system is left to its own devices, most of the carbon will be out of it by 2060 or 2070.’

The future will feature ideas that are barely glints in engineers’ eyes right now – devices in space to harness the solar wind, say, or the rotational energy of the earth; or devices to shade the planet with mirrors placed at the Lagrange Point between the sun and the earth. How do I know? Because ingenuity is rampant as never before in this massively networked world and the rate of innovation is accelerating, through serendipitous searching, not deliberate planning. When asked at the Chicago World Fair in 1893 which invention would most likely have a big impact in the twentieth century, nobody mentioned the automobile, let alone the mobile phone. So even more today you cannot begin to imagine the technologies that will be portentous and commonplace in 2100.

They may not even tackle man-made carbon, but may go for the natural cycle instead. Each year more than 200 billion tonnes of carbon are removed from the atmosphere by growing plants and plankton, and 200 billion tonnes returned to it by rotting, digestion and respiration. Human activity adds less than ten billion tonnes to that cycle, or 5 per cent. It cannot be beyond the wit of twenty-first century humankind to nudge the natural carbon cycle into taking up 5 per cent more than it releases by fertilising desert stretches of the ocean with iron or phosphorus; by encouraging the growth of carbon-rich oceanic organisms called salps, which sink to the bottom of the ocean; or by burying ‘biochar’ – powdered charcoal made from crops.

The way to choose which of these technologies to adopt is probably to enact a heavy carbon tax, and cut payroll taxes (National Insurance in Britain) to the same extent. That would encourage employment and discourage carbon emissions. The way not to get there is to pick losers, like wind and biofuel, to reward speculators in carbon credits and to load the economy with rules, restrictions, subsidies, distortions and corruption. When I look at the politics of emissions reduction, my optimism wobbles. The Copenhagen conference of December 2009 came worryingly close to imposing a corruptible and futile system of carbon rationing, which would have hurt the poor, damaged ecosystems and rewarded bootleggers and dictators.

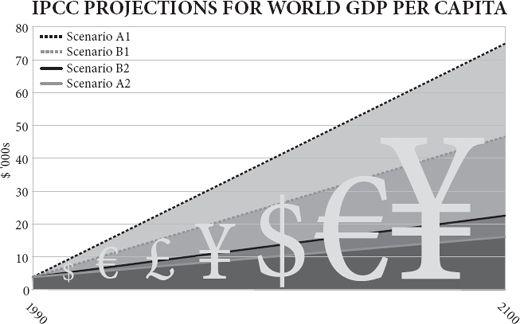

Remember I am not here attempting to resolve the climate debate, nor saying that catastrophe is impossible. I am testing my optimism against the facts, and what I find is that the probability of rapid and severe climate change is small; the probability of net harm from the most likely climate change is small; the probability that no adaptation will occur is small; and the probability of no new low-carbon energy technologies emerging in the long run is small. Multiply those small probabilities together and the probability of a prosperous twenty-first century is therefore by definition large. You can argue about just how large, and therefore about how much needs to be spent on precaution; but you cannot on the IPCC’s figures make it anything other than very probable that the world will be a better place in 2100 than it is today.

And there is every reason to think that Africa can share in that prosperity. Despite continuing war, disease and dictators, inch by inch its population will stabilise; its cities will flourish; its exports will grow; its farms will prosper; its wildernesses will survive and its people will experience peace. In the mega-droughts of the ice ages, Africa could support very few early hunter-gatherers; in a warm and moist interglacial, it can support a billion mostly urban exchanger-specialisers.

The catallaxy: rational optimism about 2100

In this book I have tried to build on both Adam Smith and Charles Darwin: to interpret human society as the product of a long history of what the philosopher Dan Dennett calls ‘bubble-up’ evolution through natural selection among cultural rather than genetic variations, and as an emergent order generated by an invisible hand of individual transactions, not the product of a top-down determinism. I have tried to show that, just as sex made biological evolution cumulative, so exchange made cultural evolution cumulative and intelligence collective, and that there is therefore an inexorable tide in the affairs of men and women discernible beneath the chaos of their actions. A flood tide, not an ebb tide.

Somewhere in Africa more than 100,000 years ago, a phenomenon new to the planet was born. A Species began to add to its habits, generation by generation, without (much) changing its genes. What made this possible was exchange, the swapping of things and services between individuals. This gave the Species an external, collective intelligence far greater than anything it could hold in its admittedly capacious brain. Two individuals could each have two tools or two ideas while each knowing how to make only one. Ten individuals could know between them ten things, while each understanding one. In this way exchange encouraged specialisation, which further increased the number of different habits the Species could have, while shrinking the number of things that each individual knew how to make. Consumption could grow more diversified, while production grew more specialised. At first, the progressive expansion of the Species’ culture was slow, because it was limited by the size of each connected population. Isolation on an island or devastation by a famine could reduce the population and so diminish its collective intelligence. Bit by bit, however, the Species expanded both in numbers and in prosperity. The more habits it acquired, the more niches it could occupy and the more individuals it could support. The more individuals it could support, the more habits it could acquire. The more habits it acquired, the more niches it could create.

The cultural progress of the Species encountered impediments along the way. Overpopulation was a constant problem: as soon as the capacity of the local environment to support the population began to suffer, so individuals began to retreat from specialisation and exchange into defensive self-sufficiency, broadening their production and narrowing their consumption. This reduced the collective intelligence they could draw upon, which reduced the size of the niche they occupied, putting further pressure on population. So there were crashes, even local extinctions. Or the Species found itself expanding in numbers but not in living standards. Yet, again and again the Species found ways to recover through new kinds of exchange and specialisation. Growth resumed.

Other impediments were of the Species’ own making. Equipped by their animal ancestry with an ambitious and jealous nature, individuals were often tempted to predate upon and parasitise their fellows’ productivity – to take and not to give. They killed, they enslaved, they extorted. For millennium after millennium this problem remained unsolved and the expansion of the Species, both its living standards and its population, was sporadically slowed, set back and reversed by the enervating greed of the parasites. Not all of the hangers-on were bad: there were rulers and public servants who lived off the traders and producers but dispensed justice and defence, or built roads and canals and schools and hospitals, making the lives of the specialise-and-exchange folk easier, not harder. These behaved like symbionts, rather than parasites (government can do good, after all). Yet still the Species grew, both in numbers and in habits, because the parasites never quite killed the system off which they fed.

Around 10,000 years ago, the pace of the Species’ progress leapt suddenly ahead thanks to the suddenly greater stability of the climate, which allowed the Species to co-opt other species and enable them to evolve into exchange-and-specialise partners, generating services for the Species in exchange for their needs. Now, thanks to farming, each individual had not only other members of the Species working for her (and vice versa), but members of other species as well, such as cows and corn. Around 200 years ago, the pace of change quickened again thanks to the Species’ new ability to recruit extinct species to its service as well, through the mining of fossil fuels and the releasing of their energy in ways that generated still more services. By now the Species was the dominant large animal on its planet and was suddenly experiencing rapidly rising living standards because of falling birth rates. Parasites plagued it still – starting wars, demanding obedience, building bureaucracies, committing frauds, preaching schisms – but the exchange and specialisation continued, and the collective intelligence of the Species reached unprecedented levels. By now almost the entire world was connected by a web so that ideas from everywhere could meet and mate. The pace of progress picked up once more. The future of the Species was bright, though it did not know it.

Onward and upward

I have presented the case for sunny optimism. I have argued that now the world is networked, and ideas are having sex with each other more promiscuously than ever, the pace of innovation will redouble and economic evolution will raise the living standards of the twenty-first century to unimagined heights, helping even the poorest people of the world to afford to meet their desires as well as their needs. I have argued that although such optimism is distinctly unfashionable, history suggests it is actually a more realistic attitude than apocalyptic pessimism. ‘It is the long ascent of the past that gives the lie to our despair,’ said H.G. Wells.

These are great sins against conventional wisdom. Worse, they may even leave the impression of callous indifference to the fact that a billion people have not enough to eat, that a billion lack access to clean water, that a billion are illiterate. The opposite is true. It is precisely because there is still far more suffering and scarcity in the world than I or anybody else with a heart would wish that ambitious optimism is morally mandatory. Even after the best half-century for poverty reduction, there are still hundreds of millions going blind for lack of vitamin A in their monotonous diet, or watching their children’s bellies swell from protein deficiency, or awash with preventable dysentery caused by contaminated water, or coughing with avoidable pneumonia caused by the smoke of indoor fires, or wasting from treatable AIDS, or shivering with unnecessary malaria. There are people living in hovels of dried mud, slums of corrugated iron, or towers of soulless concrete (including the ‘Africas within’ the West), people who never get a chance to read a book or see a doctor. There are young boys who carry machine guns and young girls who sell their bodies. If my great grand-daughter reads this book in 2100 I want her to know that I am acutely aware of the inequality of the world I inhabit, a world where I can worry about my weight and a restaurant owner can moan about the iniquity of importing green beans by air from Kenya in winter, while in Darfur a child’s shrunken face is covered in flies, in Somalia a woman is stoned to death and in Afghanistan a lone American entrepreneur builds schools while his government drops bombs.

It is precisely this ‘evitable’ misery that is the reason for pressing on urgently with economic progress, innovation and change, the only known way of bringing the benefits of a rising living standard to many more people. It is precisely because there is so much poverty, hunger and illness that the world must be very careful not to get in the way of the things that have bettered so many lives already – the tools of trade, technology and trust, of specialisation and exchange. It is precisely because there is still so much further to go that those who offer counsels of despair or calls to slow down in the face of looming environmental disaster may be not only factually but morally wrong.

It is a common trick to forecast the future on the assumption of no technological change, and find it dire. This is not wrong. The future would indeed be dire if invention and discovery ceased. As Paul Romer puts it: ‘Every generation has perceived the limits to growth that finite resources and undesirable side effects would pose if no new recipes or ideas were discovered. And every generation has underestimated the potential for finding new recipes and ideas. We consistently fail to grasp how many ideas remain to be discovered.’ By far the most dangerous, and indeed unsustainable thing the human race could do to itself would be to turn off the innovation tap. Not inventing, and not adopting new ideas, can itself be both dangerous and immoral.

How good could it get?

Futurology always ends up telling you more about your own time than about the future. H.G. Wells made the future look like Edwardian England with machines; Aldous Huxley made it feel like 1920s New Mexico on drugs; George Orwell made it sound like 1940s Russia with television. Even Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov, more visionary than most, were steeped in the transport-obsessed 1950s rather than the communication-obsessed 2000s. So in describing the world of 2100, I am bound to sound like somebody stuck in the world of the early twenty-first century, and make laughable errors of extrapolation. ‘It’s tough to make predictions,’ joked somebody, perhaps Yogi Berra: ‘especially about the future.’ Technologies I cannot even conceive will be commonplace and habits I never knew human beings needed will be routine. Machines may have become sufficiently intelligent to design themselves, in which case the rate of economic growth may by then have changed as much as it did at the start of the industrial revolution – so that the world economy will be doubling in months or even weeks, and accelerating towards a technological ‘singularity’ where the rate of change is almost infinite.

But here goes, none the less. I forecast that the twenty-first century will show a continuing expansion of catallaxy – Hayek’s word for spontaneous order created by exchange and specialisation. Intelligence will become more and more collective; innovation and order will become more and more bottom-up; work will become more and more specialised, leisure more and more diversified. Large corporations, political parties and government bureaucracies will crumble and fragment as central planning agencies did before them. The

Bankerdämmerung

of 2008 swept away a few leviathans but fragmented and short-lived hedge funds and boutiques will spring up in their place. The collapse of Detroit’s big car makers in 2009 leaves a flock of entrepreneurial startups in charge of the next generation of cars and engines. Monolithic behemoths, whether private or nationalised, are vulnerable as never before to this Lilliputian assault. They are steadily being driven extinct not just by small firms, but by ephemeral aggregations of people that form and reform continuously. The big firms that survive will do so by turning themselves into bottom-up evolvers. Google, dependent on millions of instantaneous auctions to raise revenue from its AdWords, is ‘an economy unto itself, a seething laboratory’, says Stephen Levy. But Google will seem monolithic compared with what comes next.

The bottom-up world is to be the great theme of this century. Doctors are having to get used to well-informed patients who have researched their own illnesses. Journalists are adjusting to readers and viewers who select and assemble their news on demand. Broadcasters are learning to let their audiences choose the talent that will entertain them. Engineers are sharing problems to find solutions. Manufacturers are responding to consumers who order their products

à la carte

. Genetic engineering is going to become open-source, where people, not corporations, decide what combinations of genes they want. Politicians are increasingly corks tossed on the waves of public opinion. Dictators are learning that their citizens can organise riots by text message. ‘Here comes everybody’ says the author Clay Shirky.

People will more and more freely find ways to exchange their specialised production for diversified consumption. This world can already be glimpsed on the web, in what John Barlow calls ‘dot-communism’: a workforce of free agents bartering their ideas and efforts barely interested in whether the barter yields ‘real’ money. The explosion of interest in the free sharing of ideas that the internet has spawned has taken everybody by surprise. ‘The online masses have an incredible willingness to share’ says Kevin Kelly. Instead of money, ‘peer producers who create the stuff gain credit, status, reputation, enjoyment, satisfaction and experience’. People are willing to share their photographs on Flickr, their thoughts on Twitter, their friends on Facebook, their knowledge on Wikipedia, their software patches on Linux, their donations on GlobalGiving, their community news on Craigslist, their pedigrees on Ancestry.com, their genomes on 23andMe, even their medical records on PatientsLikeMe. Thanks to the internet, each is giving according to his ability to each according to his needs, to a degree that never happened in Marxism.

This catallaxy will not go smoothly, or without resistance. Natural and unnatural disasters will still happen. Governments will bail out big corporations and big bureaucracies, hand them special favours such as subsidies or carbon rations and regulate them in such a way as to create barriers to entry, slowing down creative destruction. Chiefs, priests, thieves, financiers, consultants and others will appear on all sides, feeding off the surplus generated by exchange and specialisation, diverting the life-blood of the catallaxy into their own reactionary lives. It happened in the past. Empires bought stability at the price of creating a parasitic court; monotheistic religions bought social cohesion at the price of a parasitic priestly class; nationalism bought power at the expense of a parasitic military; socialism bought equality at the price of a parasitic bureaucracy; capitalism bought efficiency at the price of parasitic financiers. The online world will attract parasites too: from regulators and cyber-criminals to hackers and plagiarists. Some of them may temporarily throttle their generous hosts.