The Real Story of Ah-Q

Read The Real Story of Ah-Q Online

Authors: Lu Xun

Tags: #Lu; Xun, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Fiction, #General, #China, #Classics, #Short Stories, #China - Social life and customs

PENGUIN

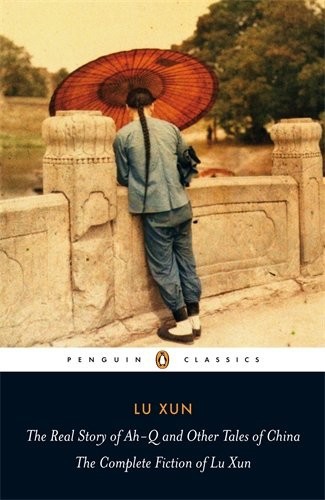

THE REAL STORY OF AH-Q AND OTHER TALES OF CHINA

LU XUN

is one of the paradigmatic figures of twentieth-century Chinese literature, celebrated during and since his lifetime for his powerful diagnoses of his nation’s social and political crisis, and for his contributions to reinventing the vernacular as a literary language. Born in 1881 into a scholar-gentry family in Shaoxing (south-east China), he was thoroughly schooled as a child in China’s classical literary heritage. After abandoning in 1899 the orthodox Confucian path of studying for the imperial civil service examinations, Lu Xun read widely in translations of foreign literature and applied himself to Western science, first in China and then in Japan, where he began training as a doctor. Intensely troubled by his country’s weakness in the face of foreign imperialism, at the age of twenty-five he decided to give up medicine for a career in literary and cultural reform. In 1918, the forceful iconoclasm of his first short story in vernacular Chinese, ‘Diary of a Madman’, helped propel him to the centre of the New Culture Movement of the late 1910s – modern China’s pivotal moment of westernizing cultural revolution. The two volumes of short fiction he produced between 1918 and 1925,

Outcry

and

Hesitation

, won broad acclaim for their highly crafted portrayals of a China in a state of spiritual emergency – of its superstition, backwardness, poverty and complacence. Like many radical intellectuals of his time, Lu Xun began to look leftwards after the rise to power of the repressively right-wing Nationalist Party in the late 1920s. Despite his public commitment to Marxist literary ideals and his posthumous canonization by Mao Zedong, Lu Xun’s final years were spent mired in squabbles with the Chinese Communist Party’s representatives of ideological orthodoxy. When he died of tuberculosis in 1936, he bequeathed to modern Chinese letters a contradictory legacy of cosmopolitan independence, polemical fractiousness and anxious patriotism that continues to resonate in Chinese intellectual life today.

JULIA LOVELL

has translated the novels

I Love Dollars

by Zhu Wen,

Serve the People

by Yan Lianke and

A Dictionary of Maqiao

by Han Shaogong. She has also edited and translated in part

Lust, Caution

, a collection of short stories by Eileen Chang. A lecturer in Chinese history at the University of London, she is the author of

The Great Wall: China against the World, 1000

BC

–

AD

2000

and

The Politics of Cultural Capital: China’s Quest for a Nobel Prize in Literature

.

YIYUN LI

grew up in Beijing and moved to the United States in 1996. Her stories and essays have been published in the

New Yorker

,

Best American Short Stories

,

O Henry Prize Stories

and elsewhere. Her debut collection,

A Thousand Years of Good Prayers

, won the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, PEN/Hemingway Award and

Guardian

First Book Award; it was also shortlisted for the Orange Prize for New Writers. She was selected by

Granta

as one of the twenty-one Best Young American Novelists under thirty-five. Her first novel,

The Vagrants

, was recently published.

Other Tales of China

Translated with an Introduction by

JULIA LOVELL

With an Afterword by

YIYUN LI

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

This translation first published in Penguin Classics 2009

Translation and editorial material copyright © Julia Lovell, 2009

Afterword copyright © Yiyun Li, 2009

All rights reserved

The moral right of the translator and editors has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-119418-9

I would like to thank particularly Bonnie S. McDougall for her meticulous reading of the Introduction and translation; the text has been enormously improved by her clear-sighted literary and linguistic revisions. I am extremely grateful to Vicki Yu-yun Chiu and Saiyin Sun for further invaluable recommendations and corrections; Saiyin Sun additionally made available her doctoral thesis on Lu Xun, which contained important new insights into Lu Xun’s personality and behaviour through the 1920s. I owe many additional thanks to Tommy McClellan for allowing access to teaching notes that shed invaluable light on important points of detail in stories such as ‘The Real Story of Ah-Q’. Sarah Coward carried out a superbly sharp-eyed copy-edit of the manuscript, of which I am most appreciative. I would like to thank also Robert Macfarlane and Thelma Lovell for their very helpful comments on the Introduction and translation. I have benefited greatly from access to earlier translations of Lu Xun’s work, especially the versions by Gladys Yang and Yang Xianyi and by William Lyell, both of which have frequently helped to clarify ambiguities in my understanding of the text. Both their translations tackle the stylistic and linguistic challenges of finding an English idiom for Lu Xun with an admirable combination of rigour and creativity that I have tried hard to emulate. All errors and infelicities that remain are, of course, my own.

1881

Born Zhou Shuren in Shaoxing, south-east China.

1884

Following its defeat of the Chinese navy, France asserts control of Indo-China.

1893

Grandfather imprisoned (on suspended death sentence) for corruption in the civil service examinations.

1894–5

China defeated in first Sino-Japanese War.

1896

Father dies after consistent misdiagnosis by Chinese doctors.

1898

Leaves home to study at the Jiangnan Naval Academy in Nanjing. Returns briefly to pass the first, district level of the civil service examination.

Influenced by reformist intellectuals such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, the Guangxu emperor issues a series of radical, reforming edicts (the ‘Hundred Days’ Reforms’). The conservative empress dowager Cixi responds by putting the emperor under house arrest and executing some of the leaders of the reform movement.

1899

Transfers to the School of Mines and Railways in Nanjing. Refuses to return to Shaoxing for the second and third levels of the civil service examination.

1900

Foreign (mainly Japanese, Russian, British, American and French) troops enter Beijing and bring to an end the Boxer Rebels’ siege of the foreign legations. The Qing government agrees to an indemnity of 450 million taels of silver (

c.

£67 million).

1902

Graduates and leaves China for Tokyo on a government scholarship; begins studying Japanese language.

1903

Cuts off his queue – the long braid that the Manchu Qing dynasty forced all Chinese men to wear as a public symbol of their submission to Manchu rule after 1644. Completes his first translation, of Jules Verne’s

De la terre à la lune

(from Japanese).

1904

Leaves Tokyo for medical school in rural Sendai.

1905

The Qing government abolishes the old-style civil service examinations.

1906

Abandons medical studies. Returns to Shaoxing to take part in a marriage arranged by his mother. Soon after, returns to Tokyo without his wife but with his younger brother Zhou Zuoren.

1907

An attempt, with Zhou Zuoren, to launch a new literary magazine,

New Life

, fails.

Qiu Jin, a female revolutionary, is arrested and executed in Shaoxing for an alleged plot against the Qing government.

1908

Publishes ‘On the Power of Mara Poetry’, acclaiming the power of the individual literary genius to awaken a nation.

1909

Translates with Zhou Zuoren and publishes a two-volume collection of foreign fiction, which barely sells. Returns to China and begins teaching physiology and chemistry at the south-eastern city of Hangzhou.

1911

Writes his first short story, in classical Chinese, ‘Nostalgia’. The Qing dynasty is toppled by republican revolution.

1912

Sun Yat-sen briefly becomes the first president of the new Republic before ceding leadership to Yuan Shikai, a former Qing general.

Disappointed by the aftermath of the Revolution, Lu Xun leaves the south-east to take up a job in the new Ministry of Education in Nanjing, then Beijing, where he absorbs himself in antiquarian research.

1913

‘Nostalgia’ published in the journal

Short Story Monthly

.

1915

The progressive journal

New Youth

is founded by Chen Duxiu. The Japanese government serves Yuan Shikai with their Twenty-One Demands, asserting greater Japanese economic and political sovereignty over areas of Manchuria and Mongolia.

1916

Yuan Shikai dies, soon after widespread resistance to his attempt to declare himself emperor breaks out. Military and political control of China lapses into the hands of warlords. Cai Yuanpei becomes chancellor of Beijing University, assembling about him many of the key intellectual players in the New Culture Movement.

1917

An attempt by Zhang Xun, a local military governor, to restore the Manchu dynasty is swiftly defeated by warlords.

Qian Xuantong, an editor of

New Youth

, asks Lu Xun to write something for the journal.

1918

His first vernacular short story, ‘Diary of a Madman’, published in

New Youth

under the pseudonym Lu Xun.

1919

Sets up home in Beijing with his mother, his wife, his two brothers and their Japanese wives.

On 4 May, violent anti-imperialist demonstrations and strikes break out in Beijing in protest against the decision at Versailles to award Japan territorial concessions in north-east China.

1921

‘The Real Story of Ah-Q’ serialized.

The Chinese Communist Party is founded in Shanghai. Sun Yat-sen forms a Nationalist Party government in Guangzhou. The Beijing government establishes the vernacular as the national language for textbooks.

1922

Completes his first collection of short fiction,

Outcry

(published the following year).

1923–4

Publishes his pioneering

Brief History of Chinese Fiction

. Following estrangement from Zhou Zuoren, moves out to a separate residence with his mother and wife. Takes various teaching posts in Beijing colleges while still working at the Ministry of Education.

Sun Yat-sen forms a United Front between the Nationalist Party and the Communist Party, in exchange for Soviet financial and military aid.

1925

Publishes a collection of essays,

Hot Air

. Begins a love affair with Xu Guangping, a former student.

Sun Yat-sen dies of liver cancer. Violent anti-imperialist protests break out across Chinese cities after British-directed police in Shanghai kill eleven demonstrators demanding the release of Chinese students imprisoned by the British. The Nationalist–Communist alliance launches the Northern Expedition, winning a series of victories against warlords in southern and eastern China. Major writers of the New Culture Movement begin to convert to Marxism.

1926

Publishes his second collection of short fiction,

Hesitation

. Several of his students are shot and killed by Beijing’s warlord government in a peaceful demonstration. He leaves his job at the Ministry of Education after publicly attacking in print his minister. Lu Xun and Xu Guangping leave Beijing that summer to take up teaching posts in Xiamen (south-east China) and Guangzhou, respectively.

1927

Joins Xu Guangping in Guangzhou; from there they move together to Shanghai. Publishes a volume of prose poetry,

Wild Grass

, and two further volumes of essays,

Unlucky Star

and

Grave

.

Chiang Kai-shek, Sun Yat-sen’s successor as leader of the Nationalist Party, launches the White Terror against the Communist Party, beginning a nationwide purge of left-wing activists.

1928

Publishes another volume of essays,

That’s That

, and a volume of reminiscences,

Dawn Flowers Picked at Dusk

. Begins reading and translating Marxist literary criticism. Quarrels publicly with members of the literary left.

1929

Xu Guangping gives birth to Lu Xun’s only son, Zhou Haiying.

Establishment of the Jiangxi Soviet in south-east China.

1930

Makes inaugural speech at the founding of the League of Left-wing Writers, confirming his commitment to revolutionary, proletarian literature.

Chiang Kai-shek launches his encirclement campaigns to destroy the Communists in Jiangxi.

1931

The Nationalist government executes five Communist writers, one of whom is a friend of Lu Xun. As the prelude to the 1937 outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese establish an independent state (Manchukuo) in north-east China.

1932

Publishes two further collections of essays,

Three Leisures

and

Two Hearts

.

1933

Publishes his correspondence with Xu Guangping,

Letters between Two

, and a further collection of essays,

False Freedom

.

1934

Publishes two further collections of essays,

Quasi-Romance

and

Mixed Accents

.

Eighty thousand Communist troops break out of Chiang Kai-shek’s encirclement of Jiangxi in the south-east, to embark on the Long March to Shaanxi in the north-west.

1936

Publishes his last collection of fiction,

Old Stories Retold

, and a further collection of essays,

Fringed Literature

. Quarrels openly with the Communist literary leadership in Shanghai. Dies of tuberculosis in Shanghai.

1937

Three-volume essay collection,

Pieces Written in a Semi-Concession

, published posthumously. Mao Zedong proclaims Lu Xun the ‘saint of modern China’.