The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (20 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

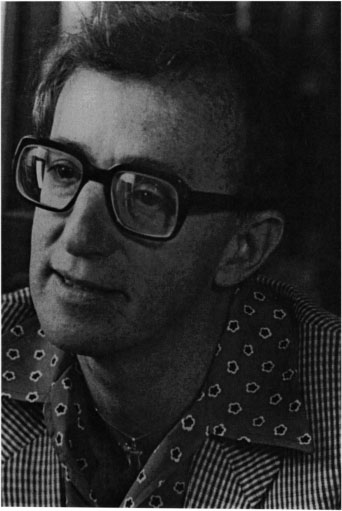

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

Bates’s happy ending, then, is too ensnared in film-within-film ambiguities to leave behind it any sense of determinacy or closure, memories and movies dissolving into each other so inextricably that it becomes difficult to decide whether Bates himself hasn’t been ironized out of existence by their interweavings. (“Sandy, Sandy,” expostulates an eccentric fan at the UFO convention who has intuited the Batesian mental reality he exists in,“you know this is exactly like one of your satires. It’s like we’re all characters in some film being watched in God’s private screening room” [p. 360].) The possibility that Bates has been annulled by the competing unrealities which he is projecting is significant because an element of the affirmation he reaches in his film’s closing scene is an affirmation of self—not untypically, one he articulates as if it were Isobel’s perception, or—to complicate things further—the perception of “this character who’s based on” her in his film. “You’re just crazy about me. You just think I’m the most wonderful thing in the world,” he tells her, “and- and you’re in love with me … despite the fact that I do a lot of foolish things, cause-cause you realize that-that down deep I’m-I’m … not evil or anything, you know? Just sort of floundering around. Just-just ridiculous, maybe. You know, j-just searching, okay?” (p. 376).

This is as close as this protagonist Allen described as “not a saint nor an angel, but a man with real problems” comes to honest self-confrontation, its defense of him as one “searching” providing the best answer the movie gives for his continuing to make films of whose purposefulness he is deeply skeptical and whose positive affect on the audience he seriously doubts. How wonderfully ironic it is, then, that at the very moment in which Bates has reached this highly significant self-affirmation, the viewer is wondering whether the self-affirmer is Bates or a character in Bates’s movie or…. Nonetheless, whether we give way to the temptation to identify Bates’s self-justification here with Woody Allen’s own rationale for filmmaking or not, this is Bates’s most sympathetic moment in

Stardust Memories,

the one which most forthrightly asks the viewer to reassess him and forgive his various trespasses. That being the case, this moment too must be ironized.

If the perspectival involutions of Bates’s self-affirmation weren’t enough to nullify its content, its replication of Guido Anselmi’s declaration at the end of

8½

may be sufficient to do that as well as to intertextually undermine whatever minimal protagonistic integrity Bates retains. After he has experienced a brief moment of clarity in which “everything is real, everything has meaning,” Guido complains, “There—everything is just as it was before, everything is confused again. But this confusion … is

me

. It’s because I am as I am, and not as I would like to be. I’m not afraid anymore—I’m not afraid of telling the truth, of admitting that I don’t know, that I seek and have not yet found. Only this way can I feel alive.”

19

Guido’s inflection is markedly less stutter-ridden and hesitant than Bates’s, his eloquent self-affirmation, delivered through interior monologue and therefore not dependent upon another’s response, seeming far more confident. Furthermore, it couldn’t typify the two directors more aptly that Fellini’s protagonist construes his lack of certainty as a necessary concomitant of being alive, whereas Allen’s protagonist identifies his existential confusion with his own ridiculousness. Nonetheless, they have in common their tentative acceptances of themselves as searchers, a similarity which nonetheless seems to push them and their films toward very different conclusions.

Guido moves from his self-affirmation to reconciliation with his wife and a joining of hands with the living and the dead from whom he’s felt alienated throughout the film; the circus ring which forms the backdrop of their parade, a progress Guido, the blocked director, directs, seems not to undermine the sincerity of his regeneration, but to confirm it. Sandy Bates’s self-affirmation, on the other hand, is revealed to be simply a sentimental ending for a movie, one which moves only a fatuous young actor who badgered Bates earlier and who interprets the film’s point as being “how … everybody should love each other” among other “serious, heavy things.” Once the Stardust Auditorium has cleared, Bates enters alone. He retrieves his sunglasses from a seat, the act suggesting, as Nancy Pogel argues, that he’s a member of the audience in a way that Guido never seems to be, but reminding us, too, that it’s the studio mavens who wear sunglasses throughout the film so that their eyes can’t be seen. He dons the sunglasses, stops to consider the blank screen for a few moments, then exits the building. As the room darkens, the only illumination left is semicircles of lights around the ceiling, the pattern they form strongly reminiscent of the lights outlining the circus ring on which

8½

fades out. As if in imitation of the Jewish comic’s strategy of outflanking anti-Semitism by anticipating and surpassing it in his/her routine, Allen incorporates into

Stardust Memories

the criticism that his work is derivative of great European directors, exploiting that objection in order to reinforce his dramatization of how completely human lives are mediated by movies.

In this film of incessantly proliferating ambiguities, a final uncertainty is whether the figure who stares at the screen at the end of

Stardust Memories

is Sandy Bates. If the ending of

Stardust Memories

constitutes a deliberate homage to the Fellini film which consistently blurs the distinction between its director and protagonist, it makes sense that, in the closing scene of Allen’s film, Dorrie, Isobel, and Daisy have become indistinguishable from the reallife actresses Charlotte Rampling, Marie Christine-Barrault, and Jessica Harper, and that the absorption of Sandy Bates into his own film’s final scene has left only Woody Allen to briefly occupy the Stardust Auditorium in grand isolation.

20

Such a culminating stripping away of levels of illusion is entirely appropriate, since all of the film’s themes—the tension between comic and tragic art, the interpenetrability of memory and desire, the capacity of the artifice of film to distort reality, the parallel capacity of erotic fantasy to distort perceptions of others, and so on—have their locus in the same individual, one whose discussion of his unresolved conflict as a filmmaker between “what I really am and what I would like myself to be” actually echoes the realization of a Fellini film protagonist whose redemptive solution to his conflict is to recognize that “I am who I am and not as I would like to be.” Whether we perceive the sunglasses retriever as Sandy Bates or Woody Allen, it is nonetheless clear that

Stardust Memories

is Allen’s most personal—and, certainly, most complex—cinematic confrontation with the issues of his relationship to his art, and one whose closing bleak demythologization of the artistic illusion undeniably reflects his inability to resolve the conflicts he’s dramatized.

21

Bates—or Allen—is finally unable to affirm the affect of his film on its audience or its effects on him: he could be, in staring up at the screen, posing to himself the same objections and questions the critic raises about the autobiographical film Guido is attempting to create in

8½

: “What a monstrous presumption to believe that others might benefit by the squalid catalogue of your mistakes! And to yourself, what good would it do you to piece together the shreds of your life, the vague memories, the shadows of the ones you didn’t know how to love?”

It is the major achievement of Allen’s film that the gradually emerging mediations and vertiginously self-consuming ironies of

Stardust Memories

constitute the only artistically legitimate response he could make to such questions.

8

Woody’s Mild Jewish Rose

Broadway Danny Rose

Why do all comedians turn out to be sentimental bores?

—Viewer at Sandy Bates Film Festival after watching the “Stardust memory” scene of Bates’s movie in

Stardust Memories

Perhaps “bores” is an inordinately harsh term with which to describe them, but the comedians who gather at the Carnegie Delicatessen in the opening scene of

Broadway Danny Rose

to trade borscht belt jokes, kibitz about the old days on the New York stand-up comedy circuit, and compete with each other to tell “the greatest Danny Rose story” are nothing if not sentimental. The pervasiveness of that sentimentality is but one of the elements which makes

Broadway Danny Rose

seem a cinematic antithesis to the prevailing jadedness of

Manhattan

’s ethos, and even more so to the relentless perspectival and affective chill of

Interiors

. Although there’s hardly an explicit reference to art—as Eve would define it, at any rate—anywhere in

Broadway Danny Rose,

it’s nonetheless a central movie to consider in the context of a discussion of Allen’s equivocal stance toward the aesthetic because it dramatizes, albeit in distincdy mediated and elliptical terms, the values Allen counterposes to the life-consecrated-to-art ethic he so conflictedly rejected in

Interiors

. If high culture artistic aspiration aroused in Allen an ambivalence he was incapable of resolving dramatically in

Interiors,

the pop culture world of Jewish American comedy elicits his sympathies so palpably that its depiction moves Allen as close as he ever comes on film to the creation of a consonantly resolved narrative founded upon a remarkably sentimental affirmation of human solidarity and morality.

1

Therefore,

Broadway Danny Rose

is as well-made a film as Allen has produced, in addition to being an object lesson in Allen’s conception of the conditions necessary to the creation of artistic closure in film narrative.

The protagonist of the comedians’ communally generated “greatest Danny Rose story” represents the contravention of everything the aesthete Eve embodies. The contrasts between Eve and Danny Rose are easy to recognize: she decorates and dresses in tasteful, monochromatically repressed earth tones, whereas his style is ’70s polyester, his polka dot shirts competing cheerfully with loud plaid jackets; she is devoted to her personally defined, individualistic conception of beauty, wanting Arthur to see the interior of a church “before it gets cluttered up with people,” whereas Danny is entirely other- directed, inquiring of every female he meets, “How old are you, darling?,” and offering the world pep talks full of self-help incantations borrowed from wise dead relatives such as “star, smile, strong” and “acceptance, forgiveness, and love.” Eve is the “very delicate” Matisse drawing she buys for Arthur at Parke- Barnet, while Danny is completely sold on “Mr. Danny Kaye and Mr. Bob Hope and Mr. Milton Berle”; she finds her only solace in the past, being desperately committed to the restoration of the lost unity of her family, which was her greatest creation and only protection, whereas he embraces a homi- letic American belief in progress and the future, insisting that the beauty of show business lies in that “Overnight, you can go from a bum to a hero.”

2

Validating Danny’s Horatio Algeresque faith in the possibility of self-transformation from “bum to hero” constitutes both the movie’s pivotal dramatic project as well as the basis for its central pun.

Perhaps the most significant distinction between the two film protagonists, however, exists in Eve’s dedication to an ideal of humanity-ennobling artistic perfection as opposed to Danny’s unequivocal commitment to artists over art. It’s not merely that the performance specialties of his clients—balloon folding, water glass playing, bird and penguin acts—bear only a parodic relation to what Eve would designate fine arts; beyond that, he seems to have deliberately sought out performers whose physical incapacities

necessarily compromise

their ability to perform their art. Far from achieving anything approaching perfect art, the performances of a number of Danny’s clients—his blind xylophonist, one-legged tap dancer and one-armed juggler—must be judged primarily on the basis of their success in overcoming the disability to which their acts unerringly draw attention. Danny is, as Jonathan Baumbach’s review of the film described him, “a one-man Salvation Army for crippled performers,”

3

and apparently it is only the utter wretchedness of Barney Dunn’s jokes that prevents Danny from representing this genial stuttering ventriloquist. Client or not, Barney (Herb Reynolds) is one of the guests at the pa- tendy sacramental Thanksgiving scene which closes the movie, Danny’s annual gathering of his showbiz low rollers manifesting not his belief in the magnitude of their talents but his sincere affection for them as people.

Accordingly, in attempting to sell his clients to hotels, rooms, and promoters, Danny invariably invokes their human qualities—the blind xylophone player is “a beautiful man,” “a fantastic individual”—rather than the virtues of their acts, Danny’s intense involvement in their lives enabling him endlessly to vouch for their characters and plead their causes for them. (The trauma of the death of one of the birds in Herbie Jayson’s act, Danny argues with a club manager, justifies his being paid despite his client having been too devastated to perform.) Simlarly, Danny is able to value even those whose lack of talent doesn’t even have the excuse of good character to recommend it. The client of Danny’s that the comedians’ “greatest Danny Rose story” concentrates on is perceived by the rest of the show business community as nothing but trouble: Lou Canova (Nick Apollo Forte) is, in the words of the owner of Weinstein’s Majestic Bungalow Colony, “a dumb, fat, temperamental has- been with a drinkin’ problem” (p. 154). The unfolding of the plot adds “womanizer” to that catalogue of Lou’s character deficits, none of which deters Danny from devoting himself unswervingly to the promotion of the Italian crooner’s career, even volunteering to waive his commissions when Lou feels financially pinched. “In business,” Danny’s father had told him, “friendly but not familiar,” but he hasn’t been able to follow that advice because, “This is personal management I’m in. You know, it’s the key word, it’s

personal

” (p. 212). His emphasis on ministering to the personal lives of his clients combined with the limitations of their talents insures that he and they remain on the outer fringes of show business. His marginality is epitomized by the fact that his most successful performers regularly abandon him for more powerful agents, and by the snapshots on his apartment wall of himself with Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett, of himself with Judy Garland, of himself with Myron Cohen—photographs in which Danny is never quite visible. In this most sentimentally egalitarian of Woody Allen’s films, it is anything but a putdown to suggest that Danny and his clients deserve each other.