The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (29 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

One of Tom’s primary virtues is that he is completely consistent because consistency is—as he habitually describes the structure of his personality—“written into my character.” His kisses are exactly what Cecilia dreamed kisses should be, but he’s confused by the fact that they don’t culminate in fade-outs. He’s always up for adventure, but he doesn’t comprehend that in New Jersey you need keys to start the cars required to make daring escapes. The stares his great white hunter’s garb and pith helmet attract from urban New Jerseyans are lost on him, the discrepancy between his pride in being “Tom Baxter, of the Chicago Baxters,” and the Depression America into which he’s escaped never seeming to register completely, either. He claims to be courageous, and he is: he battles Monk, a much larger and more brutal man, over Cecilia and is defeated only because Monk fells him with sucker punches the deceitfulness of which Tom can’t anticipate because mistrust is not “written into my charac ter.” He suffers no wounds from Monks pounding, because Hollywood heroes routinely emerge from fisticuffs unmarked, and he’s baffled when his movie currency won’t pay their check in a New Jersey restaurant. (“We’ll live on love,” he assures her once his pennilessness in this world has registered, but even Cecilia knows “That’s movie talk” [p. 387].) The familiarly Hollywood montage world of

The Purple Rose of Cairo

into which he takes Cecilia—“Trust me,” he says, urging her to follow him onto the screen (p. 442)—is as beautiful and romantic as she expected, the only problem being, as she remarks, the champagne is really ginger ale and he can use his bogus currency as legal tender to pay for it. Finally, it’s his infatuation with Cecilia that initially inspires Tom to liberate himself from the scripted inexorability of his marriage to Kitty, the nightclub singer, in the narrative of

The Purple Rose of Cairo,

the pursuit of Cecilia representing the primary expression of his newfound freedom. (To Cecilia, the plottedness of

Purple Rose

dictates that, for its characters, “things have a way of working out right”; to Tom, the script subjects him deterministically.) Tom’s commitment to Cecilia is sincere and unwavering, giving him the distinction of being perhaps the only major Woody Allen character incapable of committing adultery. As he tells the prostitutes who, charmed by his weird innocence, have offered to service him communally without charge, “Oh, I couldn’t do that….I’m hopelessly head over heels in love with Cecilia. She is all I want. My devotion is to her, my loyalties…Every breath she takes makes my heart dance” (p. 429). Prostitute Emma is deeply impressed by his recitation, assumedly recognizing pure “movie talk” when she hears it. “Where I come from,” Tom tells Cecilia immediately upon spiriting her out of the movie theater following his escape from the screen, “people, they don’t disappoint. They’re consistent. They’re always reliable.”

“Y-y-you don’t find that kind in real life” (p. 379) is Cecilia’s response. The film’s sudden cut to Gil Shepherd, whose initial appearance in the film seems sparked by Cecilia’s scene-closing line, represents Allen’s most compelling embodiment of her assertion. Gil has none of Tom’s pride in family, having changed his name from Herman Bardebedian to a more WASPish

nom de film

. Rather than continually talking about Cecilia and his devotion to her, Gil obsesses about himself and his movie career, shamelessly feeding off Cecilia’s adoration of him and the comic movies he’s made. It’s because Tom’s defection from

The Purple Rose of Cairo

threatens to undermine that career and to interfere with Gil’s ability to land the plum “serious” role of Charles Lindbergh in an upcoming biographical movie that Gil has traveled to New Jersey, and once he’s convinced Cecilia to “trust me…

please

” (p. 400), she takes him to Tom.

Gil, immediately violating his pledge to Cecilia, tries to talk Tom out of his conviction that his freedom from the screen is precious and to compel him back into the movie. Gil courts Cecilia with his real-world charm and Holly- wood-trained abilities, impressing her with the musical comedy duet they perform in a music store. The songs they play together invoke the change of fortune (“I know that soon … we’re going to cover ground. And then I’ll holler… ‘Cause the world will know, Here I go, I’m Alabammy bound” [p. 431]), youthful felicity (“She’s only twenty, And I’m twenty-one. We never worry, we’re just havin’ fun”) and happy resolutions (“Sometimes we quarrel… and maybe we fight… But then we make up/the following night” [p. 432]) which Hollywood movies routinely promised their audiences as being just around the corner. (Cecilia’s association of happy endings with ultimate meanings is compressed in her attempt to describe God to Tom: He’s “a reason for everything … otherwise, i-i-it-it’d be like a movie with no point and no happy ending” [p. 408].) Gil’s clothes contribute equally to his appeal, the nattily coordinated pastel ensemble he sports contrasting no less radically with the bark-drab garb of Depression America than Tom’s safari getup, but bearing the cachet of wealth and glamour—”You’ve got a magical glow,” Cecilia tells him—rather than the ethos of adventure yarn weirdness. Cecilia never comments on the potency of his kisses, but by the time Gil kisses her, he’s already reduced the act to pure technique: “Its a movie kiss,” he explains when she asks about kissing fellow star Ina Beasley on-screen, “You know, we professionals, we can put that, that stuff on just like that” (p. 434). In arguing his suit for her against Tom, Gil, feigning embarrassment at speaking with such sincerity, tells Cecilia that he knows it “only happens in movies” but “I love you” (p. 458). The paradox here—the scripted character has the freedom to love genuinely, the real actor loving through mimicking movie plots—is clear to and dramatically effective for the viewer; what Cecilia overlooks is the extent to which Gil is reenacting one of his movies throughout his relationship with her.

Tom leads her through their Hollywood montage “night on the town” on the other side of the screen of the Jewel Theater, Cecilia’s response to it—“My heart’s beating so fast!”—echoing the song lyric, “Heaven, I’m in heaven, And my heart beats so that I can hardly speak,” which provides the soundtrack frame of Allen’s film. At the end of this wonderful night, Cecilia finds herself on the borderline of the two realms, obliged to choose between her suitors and the worlds they represent: the beautiful black-and-white unreality of

The Purple Rose of Cairo

or the actual Hollywood to which Gil promises to take her. “Your dreams are my dreams,” Tom contends, just evading articulating the truth that he

is

Hollywood’s approximation of the dreams in Cecilia’s head. “I love you,” Tom continues his plaint, “I’m honest, dependable, courageous, romantic, and a great kisser.”

“And I’m real!” is Gil’s rebuttal (p. 456).

“You know, you know you said I had a magical glow?” Gil’s seductive case for himself begins. “But that … it’s you, you’re the one that has one.” Gil’s argument that the “magical glow” exists not in the images on the silver screen or in those “stars” who embody that glow in movies but in its down-trodden and economically beleaguered audience reaffirms the impetus which initially drew Tom out of the screen, confirming the Hollywood press agent’s contention that “The real ones want their lives fiction, and the fictional ones want their lives real” (p. 395). The tug-of-war evoked here between the claims of an artistically contrived reality as against those of actuality becomes a cen-tral theme of

Bullets Over Broadway,

Cheech’s brutal street knowledge injecting a saving vitality and realism into David Shayne’s formalistically overdetermined play. In

The Purple Rose of Cairo,

Gil’s location of the source of magic in the real world is merely rhetoric aimed at achieving his primary goal: getting Tom back into the film, thus eliminating the obstacle he poses to Gil’s career’s ascendancy.

“And even though we’ve just met,” Gil concludes his suit, “I know this is the real thing.” What finally wins Cecilia over is his stronger alliance with reality: “You’ll be fine,” she tells Tom in rejecting him. “In your world, things have a way of working out right.” (She’s unaware that the producers are considering the idea that, once Tom has returned to the screen, they’ll “turn off the projector and … burn all the prints” [p. 439] of

The Purple Rose of Cairo

so Toms flight to freedom can’t be repeated.

3

) “See, I’m a real person,” she continues, disregarding all the evidence with which she’s been confronted that Tom’s “movie talk” devotion is—ironically—more real than Gil’s glib charm and tutored courting: “No matter how… how tempted I am, I have to choose the real world” (p. 459). In Allen’s films, of course, acts of integrity and self-renunciatory pragmatism like Cecilia’s choice are abruptly rewarded by manifestations of the ugliness of the reality she has opted for. Consequently, Tom disconsolately returns to his scripted role in

The Purple Rose of Cairo

as Cecilia hurries home to pack for her trip to Hollywood. In an exact inversion of the

Stardust Memories

scene in which Sandy Bates stares up bleakly from the auditorium at the screen on which his cinematic fate has just played itself out so felicitously, Tom Baxter stares mournfully out from the screen into the empty movie theater which once harbored the happy ending so tempting he’d fled the screen in pursuit of it before returning to the plot of

The Purple Rose of Cairo

and his arranged marriage to Kitty, the nightclub singer, or to an incendiary fate far bleaker still.

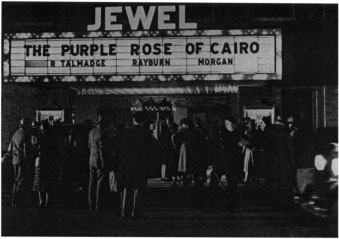

“Go, see what it is out there,” Monk upbraids Cecilia as she packs her bag at their apartment for her Hollywood trip, “It ain’t the movies! Its real life! It’s real life and you’ll be back!” Cecilia slams out of their apartment on her way to the Jewel Theater to meet Gil, and once again the prophecy that she’ll be returning to her abusive, unfaithful husband lumbers toward fulfillment. (Her repetition of the same interaction with Monk at the beginning and end of Allen’s film suggests that her life contains no more freedom of choice than does Tom Baxter’s.) That Gil won’t be waiting at the Jewel Theater when Cecilia arrives to run off with him is written not in her stars but in the script he’s been acting out with her.

In their second meeting, Gil and Cecilia recall one of the movies—

Dancing Doughboys

—in which he appeared, Cecilia joyfully reciting lines from it to him in testimony to her fan’s devotion. “I won’t be going South with you this winter,” she recalls him telling his leading lady, and Gil completes the rest of his line: “We have a little—uh—score to settle on the other side of the Atlantic.”

“‘Does this mean I won’t be seeing you ever again?’” she recites; ‘“Well, ‘ever’ is a long time,’” is his line. ‘“When you leave, don’t look back,’” she recites, concluding the

Dancing Doughboys

highly melodramatic scene (p. 433).

Gil plainly had a little score to settle with his

Purple Rose

portrayal on this side of the Atlantic, and having settled it, he’s gone. He’s “not heading South with you this winter”—he isn’t “Alabammy Bound”—or heading with Cecilia in any other direction; that was just a song he sang with her, the kind of sentimental ditty Hollywood producers inject into their movies to make the audience forget they’re irremediably married to Monk and the grinding, unending Depression of which he seems simultaneously symptom, victim, and scourge.

4

. Gil never gets to deliver his “ever is a long time” line because the next we see of him, he’s on a plane en route from New Jersey back to Holly wood, appearing a little melancholy but never looking out the window, never once looking back.

And so Allen’s

The Purple Rose of Cairo

ends on what is possibly his most emotionally compelling and completely earned pessimistic cinematic closure. (When advised by an Orion Films executive that the change to a happy ending would make millions of dollars difference in the box office receipts of

The Purple Rose of Cairo,

Allen responded, “The ending was why I made the film.”

5

) Cecilia, sunk in abandonment and disappointment, yet reluctant to return home to once again fulfill Monk’s prediction, wanders numbly into the Jewel Theater, where a new attraction,

Top Hat,

is playing. Tearfully, she begins watching Ginger Rogers dancing with Fred Astaire as he sings “Cheek to Cheek,” another Depression-era song evocative of fortuitous resolutions, happy endings. Given that the song provided the soundtrack beneath the opening credits as well, “Cheek to Cheek” here seems testimony less to ripening conditions than to the lack of change which has transpired in Cecilia’s life over the course of the film, an idea ironically pointed to through the line, “And the cares that hung around me through the week/Seem to vanish like a gambler’s lucky streak/ When we’re out together dancing cheek to cheek.” Cecilia’s “lucky streak” (“Last week I was unloved … Now… two people love me … and i- it’s-it’s the same two people” [p. 455]) has clearly vanished as well. In the course of

The Purple Rose of Cairo,

Cecilia has seen the Hollywood illusion from both inside the screen and from outside it: she now understands the overplotted, falsely reassuring, pretty unreality which the screen projects, and she’s known firsthand as well the hypocrisy which is the product of the star- making machinery, having personally experienced Gil’s Hollywood egotism, complete untrustworthiness, and real indifference to the audience of which she is part. “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?” T.S. Eliot asks in “Gerontion,” but as Cecilia watches the gorgeously romantic choreography of Fred and Ginger on the screen, knowledge gradually gives way to forgiveness, her tears drying, her eyes widening with fascination and adulation as she reenters her familiar infatuation with the images on the silver screen.

6

All traces of troubling thoughts—of her rejection of Tom and betrayal by Gil, of her imminent return to Monk, of the continuing Depression in the world outside, or of her unemployed status—have disappeared, leaving her staring up at the flickering shadows on the Jewel Theater screen with a fully rekindled, completely ecstatic joy as Allen’s film comes to a close.