The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (38 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

Both Gabe and Judy offer their literary efforts—his novel, her poems—to Rain and Michael, characters to whom they are physically attracted, thereby exploiting their work as seduction tools, the sharing of their writing signaling openness to greater intimacy far more than any desire for serious textual criticism. In one of his exchanges with the interviewer, Gabe expands upon his own confusion between the aesthetic and erotic. He intimately confesses his attraction to “kamikaze women—women who crash their plane—they’re self-destructive—but they crash it into you … If there are hurdles or obstacles” to the relationships developing, Gabe explains, they represent increased erotic inducements to pursuing it: “Maybe because I’m a writer … some dramatic or aesthetic component becomes right, and I go after that person. Its almost as if there’s a certain … some dramatic ambiance … it’s almost as if I fall in love with the person and in love with the situation in some way, and it hasn’t worked out well for me at all.”

26

As Julian Fox noticed, Gabe’s “attraction to the free-spirited Rain” dramatizes the same art/life confusion, since her allure “is as much due to her literary promise as her precocious sexuality.”

27

For Gabe—as for

Bullets Over Broadways

Sheldon Flender—eroticism and aesthetics have become inseparable and indistinguishable, both having their genesis in the ego. It’s only appropriate, then, that this movie in which Gabe appears embodies an attitude toward the formal qualities of filmic rendering as jaded as the one it enacts toward the possibilities of meaningful romance. Allen’s assurances to the press about the fictionality of

Husbands and Wives

were completely justified by the media’s deliberate oversimplification of the relationship between art and life in their reactions to the film, but Allen’s screenplay nonetheless provides significant evidence that literary plots and sexual attraction—art and life—have the same source, and that the contrivances of artistic representation are indistinguishable from the erotic treachery the movie so relendessly exposes.

Consequently,

Husbands and Wives

is the Woody Allen film in which art and life most closely—and most dishearteningly—converge with each other, the dynamic of narrative getting sourly configured as sexual desire’s correla-tive and mirror.

28

And, once again,

Hannah and Her Sisters

provides the most dramatic antithesis: the concluding Hannah/Elliot reunion and Holly/Mickey union affirm the divisibility of art and life, dramatizing the superiority of unmediated heart over the calculations of art. Subsequent Allen films will relegate art and life to disparate realms, largely by projecting good-feeling narratives hell-bent on generating upbeat resolutions: the most effective of these films,

Bullets Over Broadway,

resuscitates the art/life antinomy only to clearly dramatize the repudiation of art in favor of life. As for his education in the erotics of art and the art of erotics, Gabe has resolved to move on from his confessional novel to one “more political,” but for him, as for his creator, the perception of human nature articulated by the leader of the chorus in

Mighty Aphrodite

explains why any such project is highly unlikely to work for either of them: “Curiosity—that’s what kills us. Not muggers or that bullshit about the ozone layer. It’s our hearts and minds.”

29

The hearts and minds of the characters in

Manhattan Murder Mystery, Mighty Aphrodite,

and

Everyone Says I Love You

are substantially less egocentrically disloyal than those in

Husbands and Wives,

and even that latter film ends on the slightly leavening note of Gabe’s decision not to indulge his curiosity about Rain’s erotic attractions, resolving to let this “kamikaze woman” crash her plane into someone else. In any event,

Husbands and Wives

is the film which comes closest to repudiating the affirmations—the resiliency of the heart, the redemptiveness of memory, the reassuring, existence-structuring, meaning-imbuing capacities of art—on which earlier Allen movies close. “Maybe in the end,” Gabe ends one of his stories, “the idea was not to expect too much out of life”—or out of the art which is its distorting mirror and product, either.

15

Rear Condo

Manhattan Murder Mystery

But that’s fiction, that’s movies … I mean … I mean, you see too many movies. I’m talking about reality. If you want a happy ending, you should see a Hollywood movie.

—Judah critiquing Cliff’s interpretation of Judah’s perfect murder plot in

Crimes and Misdemeanors

The projection of human need upon reality’s ceaseless flux and the subse-quent, inevitable disillusionment of that effort often dramatized by Allen’s films is most eloquently described by a physicist, Lloyd (Jack Warden), in

September

. Asked what he sees when he looks out into the universe, Lloyd replies, “I think it’s as beautiful as you do. And vaguely evocative of some deep truth that always just keeps slipping away. But then my professional perspective overcomes me. A less wishful, more penetrating view of it. And I understand it for what it truly is: haphazard, morally neutral, and unimaginably violent.”

1

Kleinman’s characterization of reality after the fog has once again obscured the stars agrees with Lloyd’s account and with Gabe’s emotional experience in

Husbands and Wives,

while adding a note on personal consequences of this perception: “Everything’s always moving all the time … No wonder I’m nauseous.”

In their omnibus interview, Allen suggested to Stig Bjorkman that he might return to the “get what you can and move on” cinematography of

Husbands and Wives

in subsequent films because “it’s inexpensive and it gets the job done”

2

; however, Gabe’s closing line—“Is it over now? Can I go?”—seems to summarize his feelings about having been subjected to the decentered, “moving all the time” cinematography of the film, and perhaps Allen’s as well. The calculated raggedness of that technique, one reminiscent of John Cassavetes’ idiosyncratic style of shooting scenes, perfectly suits material evocative of erotic duplicity and the isolating dynamics of human desire; it’s poorly suited, however, to the projection of the more upbeat tonality which is ultimately Allen’s cinematic touchstone and trademark. “In the end, we are earth- bound,” Allen told John Lahr in 1996, invoking the emotional tenor of

Husbands and Wives

before shifting to a discussion of the antithetical (and, if successful, antidotal) mode which would predominate in his following four films: com- edy. It is comedy’s capacity, he explained, to “defy all that pulls you down, that eventually pulls you all the way down. The comedian is always involved in that attempt somehow, through some artifice or trick, to get you airborne. Being able to suggest that something magical is possible, that something other than what you see with your eyes and your senses is possible, opens up a crack in the negative.”

3

This affirmative stance belies a desperation which Allen expresses later in Lahr’s essay/interview, echoing the speech he had written for

Septembers

physicist: “The only hope any of us have is magic…. If there turns out to be no magic—and this is simply it, its simply physics—it’s very sad.”

4

The liter- alness with which three of Allen’s films—A

Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, Alice,

and “Oedipus Wrecks”—attempt cinematically to incarnate this assertion indicates that the desire to generate movie magic doesn’t inevitably produce movie magic: the “spirit box” Andrew has invented, Dr. Yang and his herbs, and the magic which installs Sheldon Mills’s mother in the skies over Manhattan all fall somewhere between transparent plot devices and jokes the film is playing on its characters. To an extent, of course, Allen’s comedy is always tottering on the brink of self-parody, and “Oedipus Wrecks” gladly tumbles over the edge in order to comically hyperbolize Mills’s obsession with his mother.

Sex Comedy

and

Alice,

on the other hand, seem uncertain how seriously to take their magical realist elements, the former suggesting that sexuality, not the spirit world, is the motivating force behind human behavior, the latter using Dr. Yang’s sorcery to precipitate a transparently generic dramatic character reversal.

5

Conveying the reality of magic has proven particularly difficult for Allen largely because of his own skepticism about its existence, the awareness he dramatized in

The Purple Rose of Cairo

and

Radio Days

of how thoroughly the human desire that magic be real can seem its own confirmation despite over-whelming evidence to the contrary. Consequently, Allen’s attempts to evoke magical moments often leave the impression conveyed by the scene (

torn Alice

in which Alice (Mia Farrow) and Eddie (Alec Baldwin) fly over Manhattan: this isn’t magic but movie magic, special effects rather than spells.

6

With the exception of

Bullets Over Broadway

(which construes magic’s stand-in, art, as egocentricity pretentiously commodified), Allen’s 1993-1996 films were dedicated in varying degrees to affirming that “the only hope we have is magic,” even if the forms that magic takes are the merely everyday sorceries: movie murder mystery plotting and detection (

Manhattan Murder Mystery),

of the transformative powers of Eros (

Mighty Aphrodite

); and the ubiquity of the human dependency upon romance

{Everyone Says I Love You)

. It is not Kleinman’s idea that “When I see something with my own eyes, I like to know that it’s really there” which pervades these films, but instead it is Allen’s more hopeful construal of art as a medium manifesting that “something other than what you see with your eyes and your senses is possible.” These movies embody the lesson learned by Mickey Sachs in

Hannah and Her Sisters,

Allen predicating his mid-’90s filmmaking career, as Sachs does his life, on the “slim reed” of “maybe”: “And I’m thinking to myself, geez, I should stop ruining my life … searching for answers I’m never gonna get, and just enjoy it while it lasts. And, you know, after all, who knows? I mean, you know, maybe there is something. I know, I know maybe’ is a very slim reed to hang your life on, but that’s the best we have. And … then I started to sit back, and I actually began to enjoy myself”

{Hannah,

p. 172).

Cynics would charge that these films are far more about Woody Allen enjoying himself than they are about projecting some philosophically portentous “maybe” on which lives might be predicated; because he’s generally honest about what he perceives as his greatest temptations in filmmaking, the best of these movies include amidst their celebrations of existence dramatic countercurrents of skepticism about their own impulses toward affirmation. In their cinematic projection of the debate Allen is conducting with himself over the human need to believe in the magical and that need’s distortion of the very thing whose existence we seek to confirm, Allen’s 1993-1996 films constitute both effective comedies and honest attempts on Allen’s part to create what he isn’t sure exists anywhere but on movie screens.

As if in reaction against the disquietingly unmoored cinematic technique of

Husbands and Wives,

Allen’s next film,

Manhattan Murder Mystery,

begins with a distinct return to his more visually stable and precisely calculated cinematic style.

7

Its steady, even pan across the New York skyline from the air culminates in a perfectly framed image of Madison Square Garden as Bobby Short plays Cole Porter’s “I Happen to Like New York” on the soundtrack, the sequence recalling, as Philip Kemp noticed, the “Rhapsody in Blue” beginning of

Manhattan

8

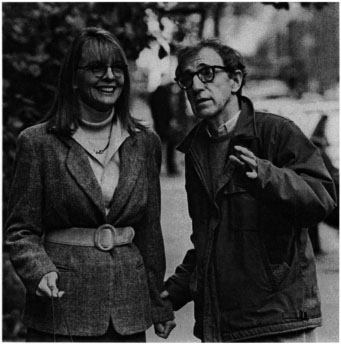

Reinforcing the sense that the world filtered through Woody Allen’s glasses has been restored to normalcy is the fact that the camera, completely ignoring the Rangers game being played on the ice and the rest of the Garden crowd, cuts immediately to and focuses steadily upon two spectators: Allen and Diane Keaton. (As the tabloids breathlessly informed their readers, Keaton had taken on the role of Carol Lipton when the estrangement between Allen and Farrow necessitated recasting the part he had written for her.

9

) The state of the marriage of Larry (Allen) and Carol (Keaton) Lipton is epitomized by the bargain of cultural sublimation they’ve struck with each other: she’ll sit through a Rangers game if he watches an entire Wagner opera with her. (She keeps her part of the agreement; he walks out of the opera because “I can’t listen to that much Wagner. I start getting the urge to conquer Poland.”) Although Carol has many of the diffident character traits of Allen’s female protagonists (she wants to do significant work in the world but isn’t sure what kind, this confusion feeding her want of self-confi- dence), she is the one who recognizes the stale peace which their marriage has become, worrying that they’re becoming “just another dull, aging couple” seeking titillation from hockey games and fascist opera—”a pair of comfortable old shoes.”