The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (9 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

The anticlimax of that ending is tempered somewhat by the dramatization of the last meeting between Annie and Alvy in which they indulge themselves in the pleasure of “kicking around old times,” and through which Allen offers the affirmation he has ready when his narrative leaves him with nothing else to affirm: memories. The soundtrack reprises Annie’s/Keaton’s lovely rendition of “Seems Like Old Times,” the performance exemplifying the growth in artistic self-confidence that Annie has achieved, at least in part, as a consequence of her relationship with Alvy. (Inherent in the sophistication of the song’s performance, ironically, is the inevitability of their relationship’s termination, one provoked by Annie’s desire to seriously pursue the singing career Alvy has encouraged her to believe she can have.) Then the screen fills with a montage of the couple’s—and the audience’s—favorite moments of their past together: of Alvy and Annie contesting live lobsters’ resistance to becoming their dinner, of the two buying books which have “death” in their titles, of Annie withdrawing the negligee he bought for her birthday from its gift box,

19

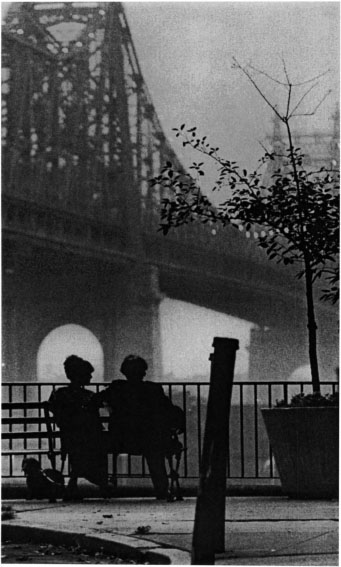

of the two kissing on FDR Drive silhouetted against the New York skyline, and so on. Alvy, in voice-over, sums it all up by explaining, “After that it got pretty late. And we both hadda go. But it was great seeing Annie again, right? I realized what a terrific person she was and-and how much fun it was just knowing her, and I-I thought of that old joke, you know.” (p. 105). The one-liner about the crazy brother who thinks he’s a chicken follows, its conclusion suggesting that his brother would have him institutionalized but “we need the eggs.”

Framed by the café table and chairs they sat in for their reunion lunch, their used plates and cups evoking an aura of pleasure spent and things used up, Annie and Alvy part on a Manhattan street, awkwardly shaking hands and then kissing, as the published script describes it, “friendly like” (p. 105). The protagonist who acknowledges having “some trouble between fantasy and reality” is left having to embrace fantasy in the form of romantic memories of Annie; given the highly sentimental “Seems Like Old Times” finale of

Annie Hall

to which we will return in the

Stardust Memories

chapter, Allen’s distinctly hedged affirmation closing the film suggests that nostalgically projected imaginary eggs are better than never having had any eggs at all.

However, even that equivocal affirmation of the human capacity for nostalgia and the affectingly bittersweet close it undergirds, are problematized by the resonating overtones of Alvy’s concession, “You know how you’re always tryin’ t’ get things to come out perfect in art because it’s real difficult in life.” Perhaps appropriately, few viewers or critics applied Alvy’s judgment to Allen’s film, declining to perceive

Annie Hall

as, in its own way, an attempt to “get things to come out perfect in art,” and therefore to be mistrusted as an aesthetically compromised vision of life. (Only Allen and Keaton, after all, know exactly how much

Annie Hall

constitutes an effort to “get things to come out perfect in art” which ended unhappily in life, and their perceptions probably differ as much as do Alvy’s and Annie’s as they analyze their relationship for their analysts.) Far from being received as a self-conscious artifice decrying its own artificiality, of course,

Annie Hall was

critically celebrated as a particularly inspired convergence of cinematic realism and artistic calculation, and it’s probably advisable not to insist too vehemently on the presence of a dynamic of critical self-referentiality in the film. Alvy’s comical effort to impress Annie with his ability to wield analytical jargon in their discussion of photography —“the medium enters in as a condition of the art form itself” (p. 40)—contains an admonition to critical restraint which is probably best to heed in this most transitional of serious Allen films. In the end,

Annie Hall

is at least as much about the disintegration of a romantic relationship as it is about art’s capacity to distort reality, the film’s hearteningly nostalgic ending discouraging viewers from applying Alvy’s suspiciousness about artistic contrivance to the Woody Allen film they’ve just seen.

In

Annie Hall,

Allen had not yet resolved to make Alvy’s—or his own—skepticism about his art and the subjective needs it fulfills for the artist a critical template according to which this film must, in turn, be evaluated. Nor—because Alvy’s play is only viewed in rehearsal—had he begun to consider the affect of art upon its audience in his films. But four years later, in

Stardust Memories,

Allen forthrightly reconfronted that issue of artistic self-referentiality, making the romantic reconstruction of actuality which is artistic rendering precisely what his movie was about. Sandy Bates—a much more jaded and conflicted artist than neophyte dramatist Alvy—spends much of

Stardust Memories

trying to devise an appropriate ending for the film he’s soon to release, his difficulty reproducing a recurrent dilemma of Allen’s own scriptwriting and filmmaking career obliquely signaled in

Annie Hall’s

alternative resolutions.

20

Bates is subjected to endless pressures by Hollywood studio executives to create an upbeat commercial ending: they want him to revise the garbage dump wasteland that is the destination of the protagonist and other train passengers in Bates’s original Bunuelian resolution into a sprightly “Jazz Heaven” close. Bates balks at this improbable ending, insisting that such a conclusion is a romantic distortion of the realities of human existence. In an ending-within-an-ending recalling

Annie Hall’s

, and anticipating the thematic resolution of

Purple Rose of Cairo,

Bates settles for closing his film with the romantic reconciliation of the Bates character and Isobel. Isobel is clearly a traditionally maternal woman whose solidity counterpoints “the dark women (Dorrie and Daisy) with all their problems” to whom Bates is masochistically attracted throughout the film. Accordingly, a “big, big kiss” between Bates’s protagonist and Isobel is the final image in Bates’s movie, the scene paralleling the happy ending of Alvy’s play, exemplifying Bates’s attempt to “get things to come out perfect in art.” Their ramifications differ, but the endings of Bates’s film and Alvy’s play converge in this: they constitute artistic resolutions dictated by what the heart hopes rather than by what the head knows.

Stardust Memories

doesn’t end with the ending of Bates’s film, of course, but extends beyond dramatizing the need the movie has served its creator to the depiction of the audience’s response to it. One viewer judges the movie “heavy,” another pedantically scrutinizes the symbolic significance of the Bates character’s Rolls Royce, the actresses who played Isobel and Daisy deplore Bates’s French kissing techniques, and an elderly Jewish viewer expresses his preference for “melodrama, a musical comedy with a plot” (p. 378). Once the audience has left the auditorium, Bates enters, stares disconsolately up at the screen on which his film avatar’s felicitous fate has recently played itself out, retrieves his sunglasses from a seat, and leaves the building, alone. It’s obvious that Bates’s downbeat exit is the scene

Annie Hall

omits, the one which necessitates that the audience of

Stardust Memories

compare the resolution of the protagonist’s movie with the resolution of the Woody Allen film they are watching.

We return to

Stardust Memories

in a later chapter to consider the effect of its film-within-film complexities on Allen’s conceptualization of the value of art to human lives; for the moment, only the alternative endings of

Annie Hall

and the disjunction between the conclusions of Bates’s film and that of

Stardust Memories

will be compared. Allen’s film never accounts for Bates’s capitulation to a happy ending for his movie—perhaps the contrasting bleakness of

Stardust Memories

close provides rationale enough. Nancy Pogel’s reading of

Stardust Memories

emphasizes its debt to

8½,

tracing Bates’s sunglasses to Fellini’s movie and suggesting that Allen’s placement of them among the seats in which the audience sat conveys the idea that, unlike Fellini’s artist, whose superiority of aesthetic sensibility is never really challenged, Bates has been director

and

audience member, Allen’s film making no claim for the supremacy of or distance between artist and audience.

21

Stardust Memories

clearly

does

dramatize how much the audience wants Bates to be different from them, an artist to admire if not worship. However, the final scene introduces a point Allen’s films repeatedly make about the artist: s/he’s one of them, an individual no more capable of imagining a way out of the human dilemma than are they.

Similarly, the variety of the audience’s responses to Bates’s film reprises the multiplicity of personal obsessions which the attendees of the Sandy Bates Film Festival have psychically invested in him and importuned the director with throughout the weekend. The possibility of any narrative conclusion—to say nothing of an entire narrative—speaking to all of their lives, to their conditions, their circumstances, and their preoccupations, is minuscule. The only difference between them and Bates is that he’s gained access to the media machinery enabling him to project his fantasies on movie screens. Produced nearly contemporaneously with the publication of sociological critiques of the American fixation upon the self such as

The Fall of Public Man

and

The Culture of Narcissism, Stardust Memories

suggests that the world is too multifarious and much too comprised of self-willed individualists driven by not-completely-sane obsessions for a film resolution dramatizing a conventionally romantic conjunction of man and woman to be anything more than an irrelevant oversimplification of life’s dilemmas and complexities, a pretty lie predicated on an obsolescent aesthetic. In

Annie Hall,

Alvy’s play indulges his own and his audience’s desire for romantic closure in art;

Stardust Memories

dramatizes how inefficacious that act of artistic indulgence is for both audience and filmmaker.

Consequently, the sampling of the film’s audience’s response which is

Stardust Memories

closing scene reflects no hint of audience gratitude for the romantic leap of faith in Bates’s ending, nor is there any indication that the movie has managed even slightly to dislodge its viewers (or its actresses) from their professional complaints and personal anxieties or given them new ways of thinking about their everyday realities. Instead, the audience’s response to Bates’s film dramatizes Allen’s earlier-cited contention that “there’s no social value in art,”

22

the viewers displaying complete obliviousness to the film’s idealistic conclusion. In terms of affect, the “big finish” of Bates’s film is utterly ineffective, its generically romantic close exhilarating only Bates’s most enthusiastic fan, whose verdict—“heavy!”—reflects nothing more than his subjective predisposition to adore anything Bates projects on the screen. This is certainly not Bates’s first film, but the rest of Alvy’s apology for his “Sunny” play seems completely applicable: “You know how you’re always tryin’ t’ get things to come out perfect in art because it’s real difficult in life.” Few scenes in Allen’s films dramatize art’s perfection and the imperfectness of life more clearly than the image of Sandy Bates staring up disconsolately at the blank screen upon which his fictional persona’s happy ending has moments before so purposelessly visualized itself.

For Bates, far more than for Alvy, the impulse to create art is inextricable from the human desire to locate in human existence the principles of order, coherence, aesthetic beauty, meaning, and the possibility for happiness. Bates derives his darker portion of this knowledge from 1981 Woody Allen, whose films had begun consistently to dramatize this desire and the inevitability of its disappointment. In

Stardust Memories,

Allen revisits and revises the sentimentally uncritical resolution of

Annie Hall,

finding little solace in the capacity of the mind to spin cheering illusions from the material of the past. From

Annie Hall

onward, Allen’s film canon progressively constitutes a protracted debate between projections of the human imagination summarized by scenes from

Annie Hall

and

Stardust Memories:

Alvy Singer’s effusion in the New Yorker theater lobby, “Boy, if life could only be like that,” and Sandy Bates’s wordless exit from a movie theater in which all images signifying erotic reconciliation and felicitous resolution of existential narrative have been erased from the screen.

4

Art and Idealization

I’ll Fake

Manhattan