The Rescue Artist (13 page)

Authors: Edward Dolnick

Tags: #Art thefts, #Fiction, #Art, #Murder, #Art thefts - Investigation - Norway, #Norway, #Modern, #Munch, #General, #True Crime, #History, #Contemporary (1945-), #Organized Crime, #Investigation, #Edvard, #Art thefts - Investigation, #Law, #Theft from museums, #Individual Artists, #Theft from museums - Norway

Hill listens to all this with what seems like utter empathy. Often, as the two men talk, the tone veers from casual and light to dark and angry and back again. Russell takes the lead, and Hill adapts at once to every shift. When Russell mentions the name of one crooked cop, Hill’s eyes narrow in disdain. “I really do hate that bastard,” Hill snarls, and it is hard to detect the well-spoken art lover beneath the venomous mask.

“Well, then, you’ve got plenty of company,” Russell says, “because I fucking hate him, too.”

Both men turn to their drinks for a moment.

Russell does most of the talking, and when he pauses between tales of how he has been done wrong, Hill catches up on domestic news. He asks after Russell’s wife and gets updates on his kids. The surgery went well? Is his son’s football team off to a good start? Hill is impressed that Tom looks so fit. Is he working out? And where did he get that tan? Has he been on holiday?

This is standard banter, but Hill appears to hang on every answer. The two compare notes on old acquaintances and run through a roster of cops and robbers they have known. The rhythm of the conversation evokes sports fans at a bar, recalling the old days. “He were a right villain, weren’t he?” Russell asks cheerily, when Hill throws out yet another name.

The reminiscences turn from past triumphs and follies generally to art cases in particular. Russell asks Hill if he recalls the affair of the two ‘eads. Years before, a pair of thieves had set out to steal a monumental Henry Moore bronze from a garden. The statue, called

King and Queen

, proved too massive to move, so the thieves took a chainsaw to the figures and cut off their heads, figuring they could at least sell those.

Russell’s usefulness to Hill is that, one way or another, he hears lots of gossip and rumors about stolen art. “I’d have no compunction about turning him in if he was doing the crimes himself,” Hill says later, “but he’s not. He just lives in that world, and he knows what’s going on.”

Hill does not try to connect with Russell by minimizing his own knowledge of art, or his enthusiasm for it. When Russell struggles to come up with the name of a stolen painting that had once floated through London’s seamier backwaters, Charley reminds him that the missing work was Bruegel’s

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery

. Russell’s interest in sixteenth-century religious art would have to multiply many times before it could qualify as negligible, but Hill rattles on happily about Bruegel for a few minutes. Hill, at least, is rapt. Pieter Bruegel, he notes, was known as Bruegel the Elder because his son, also an artist and also called Pieter, was Brueghel the Younger, but the son spelled his name with an “h,” whereas …

The fancy talk, which seems like pointless showing off, is actually showing off with a point very much in mind. Two points, in fact. One is flattery: treating Russell with respect rather than condescension costs nothing and might earn some goodwill. More important, the highfalutin talk cements the notion that, however peculiar such devotion might be, Hill really does care deeply about art. The aim is to insure that when a stolen painting makes the rounds, Russell will make sure that Charley Hill hears about it.

How much of his camaraderie with Russell and his ilk is sincere and how much put-on, Hill himself seems not to know. Certainly his disdain for dishonest cops is unfeigned, as is his belief that they are legion. “Wthout exception,” Hill says, “in every single job I’ve been involved in, there’s been a corrupt cop somewhere.” But Hill’s distrust of the good guys does not spill over into fondness for the bad guys. He is far too cynical to believe that thieves are unfortunate souls who might have been redeemed by a kind word and a helping hand at the right time. Hill is fond of invoking the great names of English history and legend, but the tales he likes best are of knights errant battling black-hearted villains. There are no Robin Hoods in Charley Hill’s Britain.

Hill’s wife is a smart, insightful woman (and, by profession, a psychologist) who has often rebuked him for taking too rosy a view of his “horrible” acquaintances. Charley, she says, makes the mistake of thinking that because his informants are trying to

do

something good—help him find stolen paintings—they

are

good. The notion makes her indignant. “These are not good people,” she insists, as she has a hundred times before. “These are bad people, and the only reason they’d help to get a painting back is so they can tell somebody—a parole officer or a judge or someone—that ‘I helped Charley Hill.’ They’re manipulative, they’ve screwed a lot of people in the past, and now they’re simply trying a new maneuver, entirely for their own benefit.”

Hill mounts a halfhearted defense, to little avail. (His acknowledgment that many of the characters he mingles with are “pretty appalling human beings” is perhaps a shade too cheerful.) The problem, his wife goes on, is that Charley decides to think the best of his dubious acquaintances ahead of time, because otherwise he could never behave in the friendly way he must if he is to forge alliances, and then he performs so convincingly that he takes himself in with his own act.

It might seem a tough position for a professional cynic, to hear himself accused by the person who knows him best of holding a naively sunny view of human nature. Hill doesn’t seem much fazed, in part because the charge of naiveté doesn’t quite hit home. His tolerance has a different source. F. Scott Fitzgerald famously observed that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” First-rate or not, many of us display such abilities every day. We scan a story on page one about astronomy and the cosmos, and then we turn to the back pages and read our horoscope to see what the day has in store for us.

When it comes to judging friends and lovers, though, people tend not to be so tolerant of contradiction. A lover who betrays us reveals his

entire

character in a new and damning light. “I thought I knew you!” we cry, in a howl of anger and bewilderment. Hill has a rare talent for viewing character in a double light. He can look at one of his criminal cronies and say, “This is someone whose company I enjoy”

and

say, “This is a dangerous person who would sell me out without a second thought.”

Hill is not merely tolerant of violent and dishonest men, though, but drawn to them. The fascination is not so much with the men themselves—often they are merely schoolyard bullies grown up—as with the opportunity they offer. Crooks mean action.

Hill’s character is a mix of contrary pieces, and “restlessness” is one of the most important. In his case, restlessness is a near neighbor of recklessness. It takes a jolt of adrenaline to give life its savor. Years ago a friend dubbed him “Mr. Risk.”

Hill is a man willing to put up with a great deal for a chance to experience something new: he insists that his motive for volunteering to jump from airplanes and to fight in Vietnam was “intellectual curiosity.” Crooks and con men, whatever else they may be, are not boring. For a man as temperamentally allergic to blandness and routine as Hill, that is a virtue almost beyond price.

“I like dealing with these people and trying to work out how they think and what they’re about,” he once said, in a moment of uncharacteristic defensiveness. “I find it a hell of a lot more interesting”—his tone had darkened and his customary belligerence had returned—”than sitting in some office pondering mankind in the abstract, or counting beans about how the rate of one kind of crime compares with the rate of some other kind.”

“The awful truth,” Hill went on, “is that I tend to like everyone and dislike everyone, including myself. I prefer the company of robust people. I suppose it’s a matter of taste. I prefer to drink a gutsy rioja to some godawful chardonnay.”

“Robust” was coy. Hill’s real preference is for people and situations that offer the enticing possibility that at any moment things could go disastrously, irretrievably wrong.

MAY 5, 1994

W

ith the discovery of

The Scream’s

frame, the police finally had the break they needed. The Norwegian police and Thune, the National Gallery’s chairman of the board, contacted Charley Hill and caught him up on the players: Johnsen, an ex-con; Ulving, an art dealer playing the role of middle man.

Hill phoned Ulving at once. “This is Chris Roberts. I’m a representative of the Getty in Europe, and I hope we can meet.” Hill gave a phone number in Belgium.

The Belgian number was a tiny ploy. To hide any connection with Scotland Yard, Hill told Ulving he was based in Brussels. The Belgian police had taken care of the phone setup as part of a thank-you for Scotland Yard’s help in recovering the Russborough House Vermeer in Antwerp a few months before.

Hill suggested to Ulving that he fly to Oslo so they could meet and negotiate the painting’s return. A good idea, Ulving said, and he suggested that Hill not come empty-handed. Half a million pounds sounded right. In cash.

The money came from Scotland Yard, which kept a cash account for undercover operations. It fell to Dick Ellis, an Art Squad detective, to sign for the money, £500,000 in used notes. Taking responsibility for so much money, even briefly, was not an assignment anyone would seek. It carried all the potential for calamity of, say, being drafted to baby-sit a prince of the realm. In a long career, Ellis had never been involved in a deal with so much cash. He stuffed the bills, bundled in slabs, into a sports bag, nearly filling it. The plan was to fly the money to Oslo first thing the next morning. It would be too early in the day to sign the money out then, so Ellis planned to leave it overnight in a Scotland Yard safe.

The bag proved too big for the safe. Ellis decided to lock it in his office. “The Yard’s a pretty secure building,” he says, “but I can tell you that was a long night.” The next morning, Ellis says dryly, “I was there on time.”

On the morning of May 5, Ellis handed the cash to a thick, burly detective, an armored car in human form, called Sid Walker.

*

Six feet tall and 230 pounds, with a deep voice and a gruff manner, Walker looked like someone best left alone. In a long undercover career, he had convinced countless criminals that he was one of them. When he was young—he was about fifteen years older than Hill or Ellis—he had gone in for wrestling and rugby, and he still came across as formidable. Sometimes too much so. “He’s been hired for more contract killings than some contract killers,” Ellis says admiringly.

Walker’s fellow cops, who gave one another a hard time almost as a matter of reflex, spoke of his coups with something approaching awe. But a few roles—shady art connoisseur, for one—lay beyond his reach. “Drugs, guns, contract killings, anything like that, and Sid was perfect,” Charley Hill remarked. “Because he looks like a gorilla, and he sounds like one.”

Despite appearances, Walker was quick-thinking, as agile mentally as he was physically—so experienced that almost nothing took him by surprise. He was well-organized, too, and he had laid down the guidelines that governed all of Scotland Yard’s undercover operations. Walker had been Hill’s mentor when the younger man first ventured undercover, and he had come to the rescue more than once when Hill had managed to offend his superior officers and get himself banished to Siberia.

Hill revered him. “He was, quite simply, the finest undercover officer of his generation,” Hill has said on more than one occasion, “and he also happens to be a personal friend whom I trust implicitly.” When the Art Squad put together its plan for retrieving

The Scream

, Hill made only one demand: Sid Walker had to be part of the team.

With the cash ready and a plan in hand, the

Scream

team set off from Scotland Yard to Oslo. There were three players: Charley Hill, playing Chris Roberts; Sid Walker, whose job was to guard Hill and head off trouble; and John Butler, the head of the Art Squad, who would stay in the background but would run the operation.

Hill arranged to meet Ulving in the lobby of the Oslo Plaza, the swankiest hotel in town, a brand-new, gleaming high-rise. Hill, Walker, and Butler had rooms on different floors. Walker would arrive first, on his own. With the help of the Norwegian police, Butler would transform his room into a command bunker for the operation. Hill would show up last, late in the evening.

On the morning of May 5, Walker strolled through security at Heathrow Airport with the £500,000 in his carry-on bag. Baggage inspections were rare in those pre-9/11 days, but airport security hadn’t been let in on the story. If someone found Walker’s money and wanted to know what he was up to, Sid would have to dream up an explanation.

Hill flew into Oslo, rented the most expensive car at the airport, a top-of-the-line Mercedes, and sped into town. Always a bold figure, he dashed on stage at the Plaza with the bravura of a Broadway star emerging, already singing, from the wings. He wore a seersucker suit, a white shirt, and a blue bow tie with big green dots, and he piled out of his Mercedes, bills crumpled in his hand for tips, beckoning one bellman to see to the car and another to grab his bags. Then he strode through the lobby to the front desk.

“Hi there,” in a loud and unmistakably American voice. “I’m Chris Roberts.”

Ulving was waiting in the lobby with Johnsen. Ulving perked up when he heard Hill, and he and Johnsen came rushing over to introduce themselves.

Sid Walker was already in the lobby, keeping a surreptitious eye on things. Not surreptitious enough, it turned out. Johnsen, a savvy and professional criminal, spotted Walker—though, for the moment, he kept silent—and recognized at once that he didn’t belong. Why was a roughneck like that hanging around the hotel?

It was ten o’clock at night. Hill told Ulving and Johnsen that after he went to his room and changed, they could meet for a drink. Soon after, the three men settled in at the Sky Bar in the hotel’s rooftop lounge. Minutes later, Walker came into the bar. Johnsen turned accusingly to Hill.

“Is he with you?”

Hesitation could mean disaster.

“Of course he is,” Hill barked at once. “He’s the guy who’s going to look after me. I’m not going to come into this town with a lot of money just to have you take it off of me.” Johnsen seemed to buy it, so Hill beckoned to Walker to come over.

The danger was that Walker had no idea about the conversation he had missed. He could only guess what Hill had been saying, and if he guessed wrong they were both in serious trouble. With Johnsen already on edge, Hill knew that the least signal from him to Walker—a raised eyebrow, for instance, as if to say “Careful now!”—was impossible.

“I saw you downstairs,” Johnsen challenged Walker.

Walker was dismissive. “Yeah. You did. What do you want me to do, sit in my room all day?”

Hill launched into the cover story he and Walker had cooked up ahead of time. Walker was an English criminal who lived in Holland and occasionally did bodyguard work for Hill.

Hill had planned to introduce Walker sooner or later. Maybe they’d gambled when they shouldn’t have. The only reason to leave Walker roaming free was the vague hope that he might turn up something intriguing. Hill hadn’t figured on Johnsen spotting the competition so quickly. Could he turn that to his advantage? Johnsen would be pleased with himself; maybe his pride in his own shrewdness would lead him to lower his guard a bit.

Hill figured the cover story rang pretty true. Walker wasn’t the kind of guy you asked a lot of questions about, because one look at him seemed enough to resolve any mystery about the line of work he was in. And it made sense that the man from the Getty would have a bodyguard to watch out for him and maybe do a bit of driving, because this was a foreign country and Hill was talking about an awful lot of money. Or so a crook might reason. The Getty would never have approved the business about a bodyguard with a criminal record, Hill knew, so he hadn’t told them that part of the story.

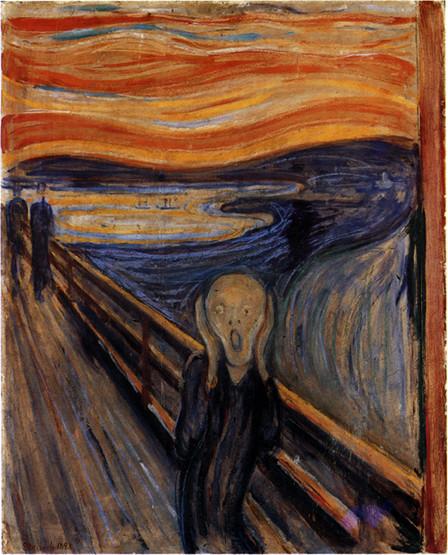

Edvard Munch,

The Scream

, 1893

tempera and oil pastel on cardboard, 73.5 × 91 cm

PHOTO: J.

Lathion; © National Gallery, Norway/ ARS

Edvard Munch painted

The Scream

in 1893. It is his rawest, most emotional work and was inspired by an actual stroll at sunset. “I stopped, leaned against the railing, dead-tired,” Munch recalled. “And I looked at the flaming clouds that hung like blood and a sword over the blue-black fjord and city…. I stood there, trembling with fright. And I felt a loud, unending scream piercing nature.”

Edvard Munch,

The Vampire

, 1893–94

oil on canvas, 109 × 91 cm

Munch Museum, Oslo. © Munch Museum /

Munch-Ellingsen Group /ARS

2004

The Vampire

, perhaps the second most famous of Munch’s paintings, was itself once stolen. Munch feared women and yearned for them; his painting, originally known as

Love and Pain

, was about the anguish that accompanies love, not about literal vampires.

Edvard Munch,

The Sick Child

, 1885–86

oil on canvas, 120 × 118.5 cm

PHOTO:

J. Lathion; © National Gallery, Norway /ARS

The Sick Child

depicts the deathbed of Munch’s sister, Sophie. The girl’s mother looks on helplessly. At one of his first shows, Munch approached

The Sick Child

only to find a rowdy crowd gathered before it, “laughing and shouting” in mockery.