The Ride of My Life (9 page)

My last period was English class. About a half-hour before school let out, I perked up my ears to the sound of an approaching rumble. Down the hallway came the tramping of Doc Martens—lots of them. Suddenly the door burst open and a dozen older punk rockers barged into the classroom. The teacher was flabbergasted by the scene, which was right out of a movie. “Mat needs to be dismissed a little early today,” one of the punkers told the teacher. She gave me a “what the hell is this about?” look and then surveyed the determined tribe of weirdos decked out in flight jackets, studded leather, combat boots, and bright hair done in Mohawks and liberty spikes—she clucked and waved me out the door. It was surreal. I picked up my books, and on the way out I half grinned, half ducked past the teacher, and my stunned classmates. With a punk rock escort to the fight, the odds were suddenly in my favor. The punkers had brought clippers and planned to crop the long blond locks off the lead knucklehead who was instigating all the trouble. After the haircut, the game plan involved holding him down, stealing his wallet, and then letting me fight him one-on-one. However, the melee never happened quite like it was supposed to. My adversary showed up at the bike racks with his jock backups, freaked out, and called everything off as a “simple misunderstanding.” The punks were pissed, but I was relieved that it hadn’t come to blows and thanked my circle-A backup squad.

The AFA contest that weekend was at the Olympic Velodrome in Carson, a city on the south side of LA. I won the contest with a run that was sprinkled with tricks like no-handers into can-cans, and nice, big fakie variations floated over the canyon between two quarterpipes. I also took home the year-end title for 14-15 Expert Ramps class. Afterward my dad, who’d flown our family to the contest in his plane, let me pilot the aircraft home (he handled takeoff and landing detail]. It was a good weekend.

We arrived back in Oklahoma on Monday and found an official-looking letter from the school board in the mailbox. It was my fate, sealed in an envelope: In bureaucratic jargon the letter informed my parents there was a school policy rigidly stipulating the number of acceptable absences per student, yadda, yadda, yadda. Because my contest schedule had taken me out of town a few school days too many, I was asked to “pursue other means of education.” It took me a second to figure out what it meant.

I was fifteen years old and kicked out of school. Permanently.

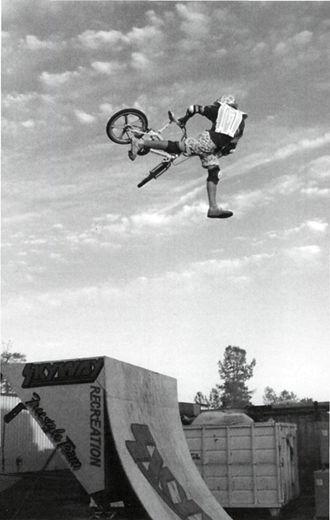

This was my first show for Skyway. They flew me out to Redding California and I showed them how skilled I was by breaking my collarbone in practice.

I wanted to get lit on fire in the chicken suit, go through the loop then jump into the lake to extinguish myself. MTV wouldn’t let me because some kid had lit himself on fire trying film his own Jackass stunt.

Career Day

Ironically years after they had kicked me to the curb, the same school asked me to come back and speak to a class for “Career Day. “At first I was going to decline and remind them that they had asked me to leave school because of my career. But, instead, I put the past behind me and decided to tell the class all about my occupation.

The day I returned to school it felt weird. I hadn’t been in the building for ten years and the look and smell brought back a few memories of my days inside the institution. Using autopilot, I found the class I was supposed to be in and stepped to the front of the room.

I started by telling the students that they could choose a traditional career like a doctor or a lawyer, and if that was what they were into, then great. More than likely, they would have a lot of support. But I also noted the great thing about life is the freedom—that it’s possible to build a career around just about anything you’re passionate about, no matter how abstract it may seem. The trade-off is the less mainstream your path, the fewer acceptances you may receive along the way. The important thing is to let your heart lead you, because every field has hard times, and even going “the traditional route” isn’t worth it unless it’s what you truly want to do.

I told them my career was a good example of a line of work that didn’t receive a lot of support. My choice of riding bikes took me out of school for tours and competitions so much that even though I made up my work, I was asked to “pursue other means of education.” Even though my career had caused the absences that led to me being kicked out, I didn’t lose my thirst for learning and growing. I’d followed my passion, and that provided me all the purpose I needed, regardless of whether it was an accepted occupation by society’s standards. “By breaking convention, I was able to make a career worthy enough to be invited to speak in front of you here today on Career Day.” I concluded with a sly smile.

The teacher who invited me had no idea I’d been kicked out, and her wide-eyed expression and the awkward pause that followed said it all.

“Why don’t we watch a video?” I suggested and popped the tape of my career highlights I’d brought with me into the classroom VCR. As the action unreeled on the TV monitor, the students got stoked, and I was glad I’d made it back to class to deliver a dose of subversion. Mission accomplished.

Airing over Chris Miller at the Gold Coast in Australia. I tore my rotator cuff on a one footed 540 days before. Circa 1990.

NINJAS, ROGUES, ROCK STARS, AND REJECTS

I was booted from school, but Mom and Dad took it in stride. Since my dad had been kicked out of his high school and he’d turned out okay, I joked with him that I was following in his footsteps (he didn’t find this quip nearly as comical as I did]. My mom, an educator, helped me create a self-learning curriculum so that I could maintain my riding career and learn what I needed to know.

My first act of self-education was to get a Ph. D. in Nintendo. For about two months solid, I stayed in my room playing Mario Brothers until my thumbs cramped up and my eyes twitched from watching a TV screen all day. Rumors of my recently completed Secret Ninja Ramp reached Dennis McCoy, prompting him to come down for a session. He glanced at my bike, covered in cobwebs, and asked what tricks I’d been working on. “I can get the hidden mushrooms and power up to beat the last boss!” I told him happily. Dennis looked at me like I was insane. I probably was. He brought me to my senses by doing what he’s so good at: merciless ridicule. He pointed out the obvious facts—I had an incredible new indoor ramp,

some upcoming contests, all the free time I wanted, and an obligation to myself to use my gifts. Dennis was right, of course. I said good-bye to Mario and Yoshi, stowed the Nintendo console under my bed, and proceeded to get back the proverbial eye of the tiger. If it was my job to ride my bike, then I was going to be Employee of the Month, every month.

I drew a modest paycheck from Skyway, but it was still more than I could spend. I hadn’t ever considered the politics of being paid to promote a product while retaining amateur status. I always thought the definition of a pro was a rider who kicked ass. I knew there were amateurs who made a lot of cash, just as there were pros who didn’t make any. The rules of the bike industry seemed to clash with the way conventional sports worked, which I thought was pretty cool. Plus, I didn’t question things that were working in my favor. My understanding of money was that my ATM card was a magic thing. I carried it in my wallet. I could stick it into a machine, punch a few numbers, and the machine spat out twenty-dollar bills. It was in

credible

.

I stimulated the local economy by making regular purchases at record stores [I’d taken a liking to hip-hop and punk rock] and stayed on top of what was playing in movie theaters (although I still considered sneaking in a sport). And of course, I bought a ton of food. With my natural craving for sugar fueled by a river of cash, I went into sweet tooth overdrive. Braum’s, the local ice cream emporium, got so used to seeing me order the same thing that they named the dish after me. A Mat Mix is a scoop of chocolate peanut butter ice cream, a second scoop of chocolate chip cookie dough, with hot fudge and caramel spread over both, then peppered with pecans and topped with a glob of whipped cream and a cherry.

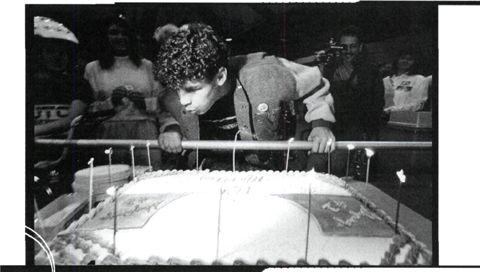

Blowing out the candles on my sixteenth birthday cake at the AFA contest in Florida. My wish was to ride forever. (Photograph courtesy of Steve Giberson)

The first AFA contest of 1988 was in Palmetto, Florida. There was more mayhem, Ohio-style, but the new wave of scuffing and rolling flatland trick combinations had many riders focused on keeping up with the Joneses rather than raging in the streets. I blew out the candles on my birthday cake just before my run. My wish was to ride forever. A lot of guys stopped riding after turning sixteen, lured away by the power of operating a car, growing up, adopting a lifestyle that was normal, by society’s standards. I vowed to be different.

But I still wanted a car.

A week after I turned sixteen, I converted a majority of my bank account into a shiny, new white Toyota Supra. It was slick and lightning-quick. I found out I had inherited my dad’s speed genes. The second time I got behind the wheel of my new Supra, I got clocked going God knows how fast in a forty-mile-per-hour zone. I was slapped with the maximum allowable fine for a reckless driving ticket, with a side order of extra points—my license was revoked. Suddenly, I had an expensive car I couldn’t use, and I had to endure many more driving classes and promise to be good before the state of Oklahoma trusted me on her streets again.

I was on the accelerated learning plan. Life was teaching me basic, but important principles, such as, “Don’t drive like a jackass,” and “Riding progress and Nintendo addiction don’t mix.” I could clearly see it was up to me to figure out my direction in life and then make it happen. A massive challenge, but also pure opportunity. The person who best understood what I truly wanted was

me

—not a teacher, guidance counselor, or a predetermined class schedule. I was enrolled in the school of hard knocks, in which the only way to learn was to jump in and figure things out as they came. Every morning I woke up and designed my day. Sometimes I knew the steps I had to take to reach whatever goal I had set for myself, and other instances I didn’t have a clue. I just knew where I wanted to go and what I wanted to do. Being kicked out of the public school system taught me the most valuable lesson I’d ever learned: I didn’t have to subscribe to another system. I could create my own culture, travel down my own path, and define my own meaning of success. I never received a frown or a happy face on my paper, but I knew when I’d done it right, and when I screwed up.