The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine (6 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine Online

Authors: James Le Fanu

The rumour about Luftwaffe âsuper-pilots' was soon scotched, but by then the research programme had developed a momentum of its own, which was a good thing because, as expected, synthesising the hormones proved to be a long and laborious task. It was not until 1948 that Dr Lewis Sarett, working for the drug company Merck, managed, by a complex chemical process, to obtain a few grams of pure Compound E. That would prove to be the mysterious Substance X.

There are two final important details, without which the remarkable potency of Compound E, soon to be renamed cortisone, would never have been realised:

For reasons that are not at all clear Dr Hench chose to use a dosage of 100mg a day. In 1948 this would have been considered a vastly excessive dose in relation to hormone requirement for other conditions. Had they used a smaller dose we now know there probably would not have been any result, and the discovery of cortisone might have been delayed for many years. Secondly, the size of the crystals in the preparations [of cortisone] happened to be dissolved at approximately the right speed. Had they been larger absorption would have been slower and the clinical remissions far less dramatic.

10

When the news of the 1949 meeting where Hench provided the flickering images of patients âbefore and after' treatment leaked out to the press, cortisone was presented as a genuine âmiracle cure'. As the medical correspondent of

The Times

reported: âWithin a few days of administration, patients were able to get out of bed and walk about, and the pain and swelling of the affected joints disappeared.'

11

No Nobel Prize has ever been awarded more rapidly. The following year Hench and Kendall travelled to Stockholm to receive their award and Hench donated part of his prize money to Sister Pantaleon â the nun who had run his rheumatology ward for twenty-three years â so she could travel to Rome to see the Pope.

12

Hench, however, was only too aware that cortisone was not a âmiracle cure' but merely controlled the symptoms and inevitably, once the treatment was discontinued, the arthritis would relapse. And then there was the problem of side-effects. When the British rheumatologist Dr Oswald Savage visited Hench at the Mayo Clinic in 1950, he found him âdepressed by the increasingly numerous reports of side-effects . . . My generation will never forget the severe complications they

produced â the moon face, the perforated and bleeding ulcers, the bruising and crushed vertebrae. It was clear this drug was so powerful it was imperative to use it safely.' What an irony to have spent a lifetime discovering a cure for an untreatable illness only to find it was so powerful as to be virtually unusable!

13

Soon the enthusiasm for treating rheumatoid arthritis with cortisone started to wane. The temporary â albeit apparently miraculous â improvement was being bought, it seemed, at too high a price.

14

And yet, just as cortisone's reputation for treating rheumatoid arthritis began to decline, so its absolutely central role in modern therapeutics began to emerge. Choose virtually any illness of unknown cause for which there is no effective treatment, however unpleasant or even life-threatening, give cortisone and see what happens.

15

In 1950, a single issue of the

Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital

featured four separate papers describing the effects of cortisone in treating chronic intractable asthma; hypersensitivity reaction to drugs; the serious disorders of connective tissue, systemic lupus erythematosis and polyarteritis nodosa; and eye diseases including iritis, conjunctivitis and uveitis.

16

The results were so uniformly good as to seem repetitive, and differed from those obtained in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in two important ways. Firstly, the benefits could be achieved at much lower doses, or by applying the cortisone externally to the skin or eyes, thus minimising the problem of side-effects. Secondly, it emerged that cortisone could in many circumstances carry a patient through a âcrisis', an acute medical problem of relatively short duration â such as an acute attack of asthma â after which the drug could be discontinued.

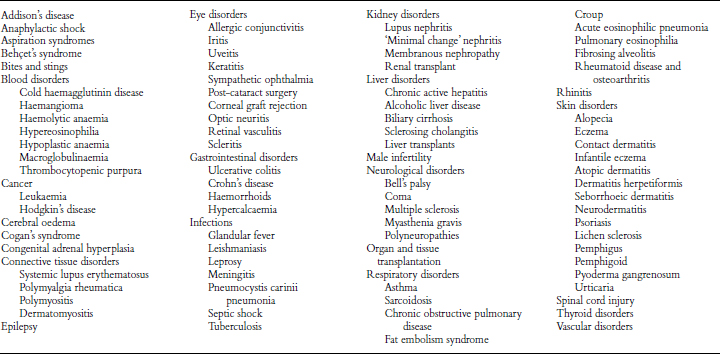

Cortisone and its derivatives, now collectively known as âsteroids', were (as shown on page 36) to completely transform the treatment of six medical specialties â rheumatology,

ophthalmology, gastroenterology, respiratory medicine, dermatology and nephrology (kidney disorders), as well as facilitating the two most remarkable therapeutic developments of the postwar years â organ transplantation and the cure of childhood cancer. Two general points deserve emphasis.

Firstly, as Hench had originally predicted, steroids are effective in a wide variety of different pathological processes, including allergy (anaphylactic shock, asthma, rhinitis, conjunctivitis and eczema); autoimmune disorders (the connective tissue disorders, haemolytic anaemia, chronic active hepatitis and myasthenia gravis); life-threatening infectious disease (septic shock, tuberculosis and meningitis); acute inflammatory disorders (polymyalgia, optic neuritis, psoriasis); and potentially lethal swelling of the brain and spinal cord following injury.

Secondly, the precise causes of many of these diseases remain unknown and herein lies the truly revolutionary significance of steroids, in that they subverted the common understanding of how medicine should progress. It would seem obvious that a proper understanding of disease would be indispensable to developing an effective treatment, but the discovery of steroids permitted doctors to pole-vault the hurdles of their own ignorance, or, mixing metaphors, the inscrutable complexity of disease was dissolved away in the acid bath of steroid therapy where, in practical terms (at least for the patient), the only really important question â âWhat will make this better?' â was resolved by the simple expedient of writing a prescription for cortisone. And yet this âpanacea' â which, despite their limitations, steroids certainly are â is a naturally occurring hormone, which brings us back to a necessary reconsideration of the functions of cortisone in the body and why it proved to be therapeutically so beneficial in so many different illnesses.

Diseases responsive to steroid therapy

(From Martindale,

The Extra Pharmacopoeia

, 31st edition, Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 1996. Readers are referred to this source for relevant references.)

Cortisone plays a crucial role in the body's ability to heal itself â the

vis medicatrix naturae

â through its effects on the process of inflammation. Consider an infected joint, which is painful and swollen because of the damage caused by invading bacteria. The white blood cells secrete powerful enzymes to destroy the bacteria and remove the damaged tissue â this is the âinflammatory' phase of healing, which is followed by âresolution', when the debris is removed and new tissue laid down. Thus, during the âinflammatory' phase, the symptoms of pain and swelling in an infected joint are as much the result of the powerful enzymes secreted by the white blood cells as part of the process of healing as of the infecting bacteria themselves. When, as happens with rheumatoid arthritis, the healing process cannot eliminate the âcause' (which is not known), the inflammation persists along with its symptoms of pain, redness and swelling, which further damages the tissues of the joint.

Cortisone in several different ways orchestrates and controls this inflammatory response and, as the fundamental pathological feature of rheumatoid arthritis is the persistence of inflammation, so cortisone will, by suppressing it, result in an improvement in symptoms. Thus Hench's real achievement was much greater than demonstrating cortisone's effectiveness in improving the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. He opened the way to the understanding that many illnesses share the unifying feature of being caused by uncontrolled or excessive inflammation. Put another way, prior to Hench there was no sense that this vast range of diseases were connected at all and it was certainly inconceivable they might all be ameliorated by a naturally occurring hormone.

This therapeutic potency of cortisone could never have been anticipated, and so it could never have been created from first principles. It is thus, just like antibiotics, best conceived of as âa gift from nature' whose discovery was quite fortuitous.

Retracing Hench's odyssey one is struck by the extraordinary improbability that the therapeutic use of steroids was ever discovered at all. It all started with a chance conversation with a patient whose symptoms had improved during an attack of jaundice, a striking phenomenon perhaps, but, as at the time rheumatoid arthritis was thought to be an infectious illness, there were no theoretical grounds for Hench to follow through the implications that some substance produced by the body would have therapeutic properties â but he did.

Hench would never have been able to fruitfully pursue his hunch that there must be a âSubstance X' had it not been for the coincidence that Edward Kendall, whose brilliant skills as a biochemist were at the time centred on an apparently unrelated area of research â the nature of the hormones secreted by the adrenal cortex â was working in the same hospital.

The quantities of hormones produced by the adrenal glands were far too small to allow their therapeutic potential to be investigated, so there the matter would have rested had it not been for the rumour about Luftwaffe âsuper-pilots' that stimulated the research programme that would eventually lead to the discovery that Substance X was, in fact, Compound E. When it came to treating his first patients with rheumatoid arthritis it was fortuitous that Hench chose a dose large enough and prepared in such a way as to give the dramatic results that generated the interest of fellow physicians to investigate the functions of the drug further. Finally, as has been noted, Hench got it right for the wrong reasons, since steroids, as it turned out, are not a particularly good treatment for rheumatoid arthritis but are very effective for many other illnesses.

*

It is only necessary to add that, fifty years later, the means by which cortisone controls the inflammatory response are still not clear. It influences the changes in the local blood supply, the attraction of cells to clear the injured tissue and the proliferation of healing tissue, but there is as yet no unifying hypothesis of how these powerful effects work together.

*

A brief account of the many other important therapeutic innovations in the treatment of the rheumatological disorders can be found in Appendix I.

1950: S

TREPTOMYCIN

, S

MOKING AND

S

IR

A

USTIN

B

RADFORD

H

ILL

T

he advent of antibiotics and cortisone created a mood of such excitement and eager anticipation of further medical advance that some form of celebration was called for. Hugh Clegg, editor of the

British Medical Journal

, saw the year 1950, the mid-point of the century, as the perfect opportunity to invite the Great and the Good to look back over recent achievements and anticipate those to come. They duly obliged, and the

BMJ

of 7 January 1950 opened with a wide-ranging review by Sir Henry Dale FRS. âWe who have been able to watch the beginnings of this great movement,' he concluded inspiringly, âmay be glad and proud to have lived through such a time, and confident that an even wider and more majestic advance will be seen by those who live on through the fifty years now opening.'

1

Similar sentiments were expressed by other distinguished knights of the profession, including Sir Henry Cohen, Professor of Medicine at Liverpool, and Sir Lionel Whitby, Regius Professor of Physic at Cambridge. But, as it turned out, the mid-point of the century proved to be more than a convenient

opportunity to reflect on the past and crystal-ball-gaze into the future. Two apparently unrelated events, each of great significance in itself, occurred later in the year, ensuring that 1950 was literally a watershed separating medicine's past from its future. The first was the demonstration that two drugs, streptomycin and PAS (para-amino salicylic acid), given together over a period of several months, resulted in a âmarked improvement' in 80 per cent of patients with tuberculosis. The second was the convincing proof that smoking caused lung cancer.

These two events represent what historians of science call âa paradigm shift', where the scientific preoccupations particular to one epoch give way to or are displaced by those of another. Thus, for the 100 years prior to 1950 the dominant paradigm had been âthe germ theory', in which medicine's main preoccupation had been to find some effective treatment for infectious diseases. Tuberculosis remained the last great challenge. Without doubt the most notorious of all human infections, the tubercle bacillus alone had proved resistant to treatment because its apparently impermeable waxy coat protected it against antibiotics like penicillin. But now, thanks to streptomycin and PAS, it seemed that even this, âthe captain of the armies of death', could be defeated. And just as the threat of infectious diseases started to recede, so it was to be replaced by a different paradigm or preoccupation â the non-infectious diseases such as cancer, strokes and heart attacks. The incrimination of smoking in lung cancer showed that the cause of these diseases might be just as specific as that for infectious illnesses, but rather than a bacterium being responsible, the culprit was people's social habits. If smoking â which was almost universal following the Second World War â caused lung cancer, then perhaps other aspects of people's lives, such as the food they consumed, might cause other diseases.