The River at the Centre of the World (37 page)

Read The River at the Centre of the World Online

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #China, #Yangtze River Region (China), #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #General, #Essays & Travelogues, #Travel, #Asia

12

The Garden Country of Joseph Rock

Not long before arriving in China for this journey I came across the oddest of picture captions, its wording quite hauntingly bizarre. It appeared in a volume of photographs taken by an eccentric Austro-American botanist-explorer named Joseph Rock; it was beneath a black-and-white picture, dated 1924, of a scene he had captured in the mountains of the Upper Yangtze valley, which showed two teenagers supporting between them a curious-looking object, like an unformed sculpture of soft clay, as tall as each of them. Whatever the object was – plasticine torpedo, melted petrol pump, alien being, squashed motorcar – it seemed to have a nose; on close inspection it looked as if, once upon a time, it had been some kind of animal.

Indeed it had. The caption read, without further comment:

‘Two Moso boys displaying a fine specimen of the Boneless Pig. After being slaughtered, boned and salted, these huge pigs are used as mattresses for up to a dozen years before being eaten. This custom, originally a protection against famine, still exists today in Muli and Yongning.’

Beg pardon? I read the caption once again, more carefully. Somehow the corralling within a single paragraph of such words and phrases as ‘pig’, ‘mattress’, ‘a dozen years’, and ‘eaten' had a surreal quality to it, and for a moment I wondered if I might have taken a surfeit of unfamiliar pills during the night.

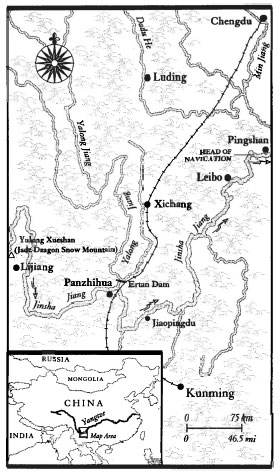

But apparently not. A day or so later, while further reading up about this corner of the world, I came across a second, equally strange reference, this time to a people like the Moso, who lived near by and who were known as the Nakhi. Among the many sterling qualities of these folk was the habit, exclusive to the lovelorn among them, of committing suicide by drinking a mixture ‘so that the vocal cords become paralysed and the victim is unable to cry for help’. Clearly the people who lived in these mountains had some rum habits – and since the mountains in question were those that begin, almost precisely, at Pingshan, where the boat traffic up the Yangtze is forced to a halt, we were now fast moving into their territory.

‘This is the demarcation line,’ writes a guide, ‘between the Han people and the Yi minority ethnic groups, and the other many ethnic minority groups of the Tibetan foothills.’ Downriver, where Lily and I had been travelling for the past weeks, had been what passes for the normality of mainstream China, or what geographers call China Proper. Ahead of us now lay the very much more wayward world of the non-Chinese, the world of those who have been incorporated into the Chinese Empire, but who live irredeemably and steadfastly beyond it. In one sense, the Pingshan city boundary is the far western expression of what might be called the Chinese Pale.

It was in Leibo, the seat of a semi-autonomous Yi county, that matters began becoming a little strange. Lily and I had managed to get rooms in a small inn, and after noodles at a restaurant run by a memorably handsome Yi woman, we retired to our respective beds, exhausted. At one in the morning there was a thunderous hammering on our doors, and a squad of Chinese goons demanded that we present ourselves for questioning before the local office of the Public Security Bureau.

We came down in our pyjamas, befuddled from sleep. There were three men, all Chinese, greasy-haired, smoking, wearing black leather jackets. Why were we in town? they wanted to know. Did we not know that foreigners were prohibited here? Was I not aware that the hotel was forbidden to accept guests from outside? Lily, who was blamed for having led an innocent abroad, was given especially harsh treatment – to which she responded by standing up to her full and daunting height, and with a stentorian voice demanding respect and courtesy from men who were, she insisted, no more than mere officials whose duties were to serve the citizenry.

It was a stunning, high-stakes outburst, the kind of response to a police inquiry that would hardly be dared in London or New York, let alone the rugged hinterlands of western China. But perhaps I didn't yet know Lily to the full: her outburst was the first of many, and it worked a charm. The three policemen became promptly craven, they offered to settle their argument with us – fully justified, since Leibo (which means ‘thunder and wave’) was very definitely a closed city – by levying a fine of about one dollar apiece, and they asked only that we leave town by sunrise.

Once the mood had become calmer and more friendly, and cigarettes were being offered around, and cups of tea, I asked one of the men why they had been so suspicious, so eager to throw us out.

‘Because of the Yi,’ he said. ‘They are a very troublesome minority.

*

They hate us. This is their town, in their eyes. Relations between us and them can be very poor. Foreigners often stir things up, and we don't like that at all.’

So we left next morning, after having had breakfast on a grassy knoll overlooking the river, which uncoiled soundlessly a thousand feet below. There were small wild strawberries here, intensely sweet. In the distance ducks squabbled and chuckled, and large brown buzzards swung lazily in the thermals. All was perfect peace. Up here the arguments between Han and Yi had no relevance at all: only the river mattered, and made all the difference. It was a ferocious-looking beast, a rich syrup, lined with white streaks, squeezed between cliffs every bit as steep and forbidding as those back in the Gorges – an unforgiving place for any shipmaster.

Downriver the Yangtze may have been impressive for its power and width and might: here it was speed and sharpness and caprice that made it all so daunting. From high up on this perch the river looked just as everyone had said it would: the most difficult and dangerous big river in the world. There were rapids every few hundred yards. I watched idly the progress through the rapids of some of the endless procession of logs that had floated downstream from the faraway forests of northern Sichuan. As each one breasted a rapid so an end rose, arching high out of the river before then tumbling back deep below the foam, and then the whole log skittered from bank to bank in a way that no ship could ever have survived. In one or two places small sampans dashed from bank to bank, taking farmers to the water meadows opposite: but I noticed they never ventured up or downstream, for fear no doubt of being caught in the currents and ripped to pieces on the rocks below.

Navigation was out of the question. But crossing the river — that, as the sampans below were demonstrating, was not by any means an impossibility. In fact the boats were providing a timely illustration, since my next destination, a couple of hundred river-miles upstream, was the most famous crossing point of all – the place where Mao Zedong and his Red Army managed to make it from the river's south side to the north, in the early summer of 1935. In fact it was sixty years before, almost to the day, when Mao managed the most decisive act of what has since come to be known as the Long March.

To reach such a place so hallowed on the Chinese political landscape is still not easy – though hardly as trying as it had been for Mao's weary and underfed young soldiers. First we found the bus to Xichang, a town well to the north of the Yangtze on a huge tributary known as the Yalong Jiang. The ride in normal circumstances might have been merely terrifying – for its first few miles the bus roared and smoked along narrow dirt roads on top of cliffs hundreds of feet above the river, and more than once a tyre smashed the retaining mound of dirt and became instantly suspended in space, those riding above that wheel looking down a dizzying void into the river foaming below. At such moments all the passengers were asked to get out, slowly and carefully, while the driver and his men pulled the unladen vehicle back onto the roadway.

My confidence in our survival was hardly helped by the braking arrangements. The driver had a contraption of small rubber hoses that ran around the back of his seat: it provided cooling water for the brake shoes, and was supplied from a bladder on the roof.

*

Whenever the bus began to run downhill, usually on a road with a sharp turn and a cliff at the bottom of the slope, the driver would reach behind him and turn a small brass spigot on the tube, allowing the water to flow; but more often than not the tube would become loose, water would flood the floor of the bus, and the driver, aware that his brakes were starting to smoke and were not arresting our downward progress one bit, would call for a passenger – me, usually, since I was sitting directly behind him – to find the tube and reconnect it, quickly! It always worked – we had the system down pat after fifty miles or so – but it made the ride more interesting than perhaps it needed to be.

Had ours been an ordinary bus service the degree of onboard terror would probably have been limited to this. But in fact ours was a bus that crossed – once the red-and-white striped barrier of the Pale was passed – into territory controlled by the Yi; and that simple anthropological reality transformed a journey that was merely frightening into an experience more akin to nightmare. For the Yi – the men huge, handsome, large-nosed, chocolate-brown, reputedly fierce, turbaned (with their hair protruding through a hole in the turban top), and the women equally attractive with blue-and-white striped costumes that in other circumstances could be thought of as charming – demanded that they had a prescriptive right to ride in this weekly bus, no matter how many were already in it and with utter disregard for any trivia like the paying of fares, or for any Han Chinese who tried to lay down the rules for running this particular service.

The bus was built for perhaps fifty passengers. By the time we were halfway to Xichang I had counted 140 people on board, as well as several dozen chickens and a pig that kept getting caught in the automatic door and might well have been rendered boneless and fit for mattress duty by the time the trip was done. Men would squeeze into the smallest of spaces that remained and still, around the next bend, another group of Yi would be waiting, would flag the bus down and insist on jamming themselves inside: woe betide any driver who might refuse. ‘I knew a man who didn't stop,’ said the driver to me in a private moment, ‘and he was never allowed to drive that route again. They threatened him and his family. They terrorized him.’

By the time the 140 were tucked inside, the vehicle was as full of humanity and assorted zoology as physics would permit – whereupon fresh members of the minority clambered up the outside and parked themselves on the roof rack. The driver had taken about as much as he could and pleaded with them to get down – in the end hurling stones at them to try to dislodge them. The men simply caught the stones and hurled them back, sending the driver scampering into the shelter of his cab and trying to drive on.

We ground slowly up a range of hills to a plateau where a weather station recorded the winter snowdrifts – and although we made it down the far side and into a tiny village with a dusty main street lined with hovels, there was a shriek of metal and a gasp of mechanical exasperation; the engine had finally given up its attempt to transport the gross overload, and the bus sagged to a halt. The huge crowd of people and animals promptly spilled out and gathered around, laughing and staring down at the driver who was trying gamely to work out what was wrong and then make repairs.

But by the time the seriousness of his situation had begun to sink in, Lily and I had already found ourselves a substitute – a friendly policewoman, a Yi herself, tall and handsome and with what Lily later enviously remarked were ‘spectacularly large breasts’. For a small sum in folding money, she agreed to drive us the remaining distance across the final range of hills to Xichang. We made it by dark: I imagined by then, and probably until late the next day, that all the Yi from the bus were still waiting, since so far as I could tell it had blown its main gasket and shattered a half-shaft at the same time – the kind of repair that even a normally ingenious Chinese driver would be hard-pressed to effect.

Xichang, blessed with so clear an atmosphere that locals call it ‘Moon City’, is China's Cape Canaveral – the principal site of the country's (currently unmanned) space effort. Satellites are lobbed up into orbit from here with impressive regularity, using the commercial workhorse rocket that is known, appropriately, as the Long March.

Once, when I was being shown around the gigantic Hughes Aircraft headquarters in southern California, I came across one of the satellites that was about to be sent up from Xichang. It was a huge drumlike communications satellite that had gone wrong sometime after its first launch; it had been plucked from orbit by the American space shuttle and brought back down to earth for repairs. At the time I saw it, it had just been bought by a consortium of businessmen in Hong Kong; a few months later it was shipped off to Xichang and eventually launched back into space by a Chinese rocket in April 1990 – inaugurating, as it happened, one of the most profound cultural revolutions the modern East has ever seen.

For the satellite soon began beaming down the various pro-grammes of the Hong Kong-based organization that the owners set up – Star TV, it was called, Satellite Television for the Asian Region. The effect of the programme was to erase, with consummate ease, a whole slew of cultural boundaries that extended from Kuwait to Japan. Within the huge broadcast footprint of the satellite, an unending diet of popular music, sports, news and old films became instantly available to anyone below who had a satellite dish – meaning that Chinese in Shanghai could watch Taiwanese films, and Indians in Bombay could dance to Seoul music, and Iranians and Koreans could watch football from Hokkaido and Singapore.