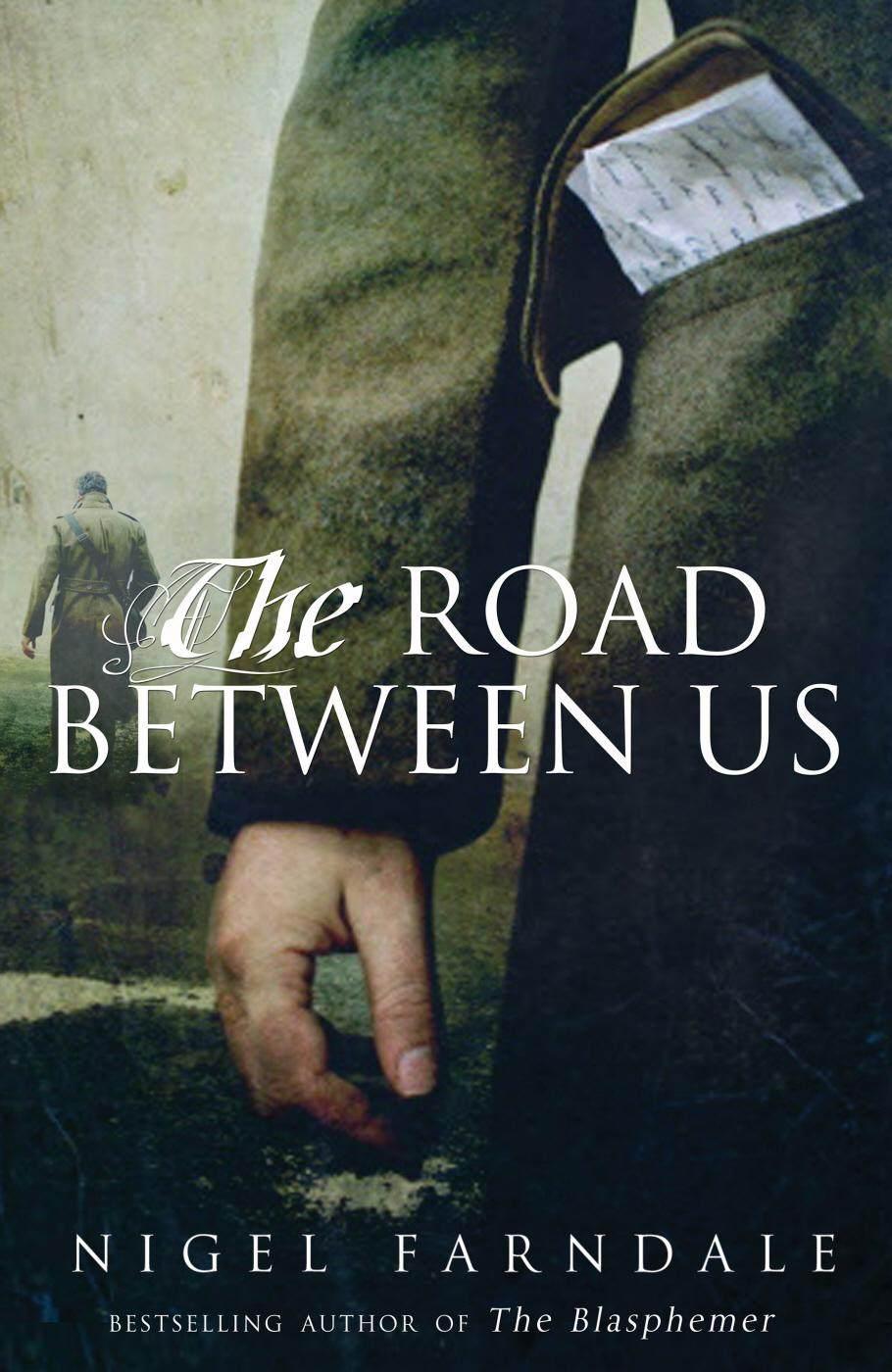

The Road Between Us

About the Book

1939:

In a hotel room overlooking Piccadilly Circus, two young men are arrested. Charles is court-martialled for ‘conduct unbecoming’; Anselm is deported home to Germany for ‘re-education’ in a brutal labour camp. Separated by the outbreak of war, and a social order that rejects their love, they must each make a difficult choice, and then live with the consequences.

2012:

Edward, a diplomat held hostage for eleven years in an Afghan cave, returns to London to find his wife dead, and in her place an unnerving double – his daughter, now grown up. Numb with grief, he attempts to re-build his life and answer the questions that are troubling him. Was his wife’s death an accident? Who paid his ransom? And how was his release linked to Charles, his father?

As dark and nuanced as it is powerful and moving,

The Road Between Us

is a novel about survival, redemption and forbidden love. Its moral complexities will haunt the reader long after the final page has been turned.

Contents

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

THE ROAD

BETWEEN US

NIGEL FARNDALE

To Alfie, Sam and Joe

‘

The heart wants what it wants, or else it does not care

.’

Emily Dickinson

PART ONE

I

FROM HIS ELEVATED VIEWPOINT, A HOTEL WINDOW THAT ALSO

serves as a balcony door, Charles Northcote cannot see the foot on which Eros is balanced. It is obscured by the statue’s outstretched wings, the feathers of which appear to be moving. The illusion may be caused by a haze of heat, or the shifting golds, reds and pinks of the surrounding neon billboards. Either way, it makes the god of love look as if he is afloat, shimmering, about his business in the night air.

With the same flickering lights reflecting their colours up on to his own hands and face – Bisto, Brylcreem, Ty-phoo tea – Charles wonders what his silhouette looks like to the eyes studying him from the bed. As his bare shoulder is resting against the top of the window frame on one side, and his feet are crossed at the bottom on the other, he must form a clean diagonal. A Nazi salute, perhaps. Thinking this inappropriate, given their situation, he stands upright and girds himself for the conversation he must have, the one he has been trying to avoid.

‘Like Piccadilly Circus down there,’ he says.

The man on the bed yawns. The muscled contours of his pale body are barely covered by a tangle of sheets. His name is Anselm and he is twenty years old and six foot three inches tall, two years younger and three inches taller than Charles. His sandy hair is parted to the right, floppily shading his eye. As he flicks it back he

says: ‘Did you bring me here just so that you could use that joke?’

‘No,’ Charles says. ‘I …’

‘I what?’

The hum of the traffic below dims as Charles closes the balcony door, and the discrete smells of the room become more noticeable: carbolic soap clouding a basin of water; human hair damp with sweat; whiskey fumes and cheap red wine. He brushes imaginary dust off the shoulder of his blue-grey RAF tunic, which is hanging over the back of a chair, a single row of braid visible above the cuff. Draped neatly over this is a pair of silk briefs. They are maroon.

‘They’re going to pack Eros off to the countryside, I hear,’ Charles continues. ‘When the war starts.’

‘There’s a war about to start? No one tells me anything.’

Charles stares at the crumpled jacket on the floor. Double-breasted. Frayed cuffs. The trousers that go with it are lying by the bed. They have a shiny seat. Between the jacket and trousers there is a trail of discarded civilian clothes: a still-knotted college tie, a single sock, a shirt half buttoned up and inside out, a snag of braces and a starched collar sprung wide, like the mouth of a man-trap.

His eyes are now on the sketchbook propped against the bed. It is open at a charcoal life drawing, a male torso without arms or head, foreshortened, viewed from below. Alongside this, as if arranged on a gallery wall, is a second drawing, this one pinned to a corkboard. Again, the model is naked, but the style is different, looser, almost abstract.

Charles crosses the room, picks them up and holds them at arm’s length, one in each hand, before sliding them under the bed. He is kneeling now, as if in childish prayer. ‘Anselm …’

‘Yes?’

Their faces are close. Though Charles’s hair is dark brown and cropped short at the back and sides, they could be brothers. Both have the lean bodies of athletes. Their mouths are sulky and full. And their jaws could have been carved from the same block of marble.

When Anselm turns away, Charles turns as well and rests the

back of his head on the mattress so that he can stare at the ghosts of cigarette smoke above him. ‘Will they let you finish your degree?’ he says in a voice he had hoped would come out warm and nonchalant, but which makes him sound as stiff as an announcer on the Empire Service.

Anselm drags on his cigarette before answering, making the tobacco crackle into the silence. ‘How would that work exactly? Do you suppose they say, “Here are your call-up papers. Report for duty immediately, or in a year’s time, if that is more convenient”?’ There is more than a trace of German in his sarcasm.

Dancing languidly on the cracked ceiling are colours from the electric hoardings outside. No one is sure when, but it is expected they will be turned off soon, until further notice. When the blackout comes into force. When the billboards finally declare war on behalf of an ungrateful nation.

‘You could just stay,’ Charles says.

‘And spend the war in an internment camp on the Isle of Man? No thank you.’ He pronounces the ‘th’ of ‘thank’ as a ‘z’.

Charles, for reasons he cannot explain, finds this pronunciation erotic. He stands, crosses the room to the sink and pulls the plug. As the soap-clouded water gurgles away, he wets a flannel under the cold tap. The night air is close and sticky, as if the heat stored in the tarmacadam roads outside is creeping up through the foundations of the building, melting it from the inside out. Had he been hoping that by closing the balcony door he would make the room feel cooler? It has had the opposite effect. He drapes the cold flannel across the back of his neck and cups his hands under the still-running tap. He splashes his face, takes several gulps of water and squeezes the material so that cold water trickles down his back.

Should they have the conversation now?

More Dutch courage is needed. Well, Irish. Single grain is his preference, with an equal measure of room-temperature water. He pours, takes a slug and swirls the amber liquid around in the tumbler. For a dead man, he reflects, he drinks an impressive

amount. Some might say too much … But what the hell.

Prost!

He empties the glass and lets the alcohol burn for a moment on the back of his tongue before swallowing.

Now?

Charles tilts his head back. As well as smoke there is condensation on the ceiling. On the mirror, too. He wipes it, stares at his reflection for a moment then returns to his position by the unmade bed. ‘Come and work for us,’ he says, holding the flannel to his forehead. ‘My father was a diplomat. I know some people in the Foreign Office.’

‘You’re assuming I’m on your side,’ Anselm says.

‘You’re no Nazi.’

‘I’m a German. I believe in holy Germany. I believe in the

Volk

, in their

Weltanschauung

.’

‘You like the uniforms, that’s not the same thing.’

Anselm flicks Charles’s ear. ‘Someone is jealous.’

‘Well, it’s true, isn’t it?’

‘There is more to the Wehrmacht than fine tailoring.’ A grin. ‘There’s also the choreography. Haven’t you seen

Triumph of the Will

?’ Anselm places four fingers vertically across his mouth.

The Englishman is laughing now. Two aesthetes together. Knowing. Ironic. When his laughter subsides he stubs out his cigarette, turns once more and, with a thumb, traces the arc of his friend’s mouth as he wipes away some tiny beads of sweat.

‘This heat,’ Charles says.

‘I know. Can you open again the window? It’s like all the fucking air has been sucked out of the room.’

Again Charles hears eroticism in the pronunciation –

fakink

– something to do with the way Anselm curls his tongue around the hard consonant in the middle, the way he comes to a stop at the end, blocking the vocal tract but continuing the airflow through his nose. His own tongue runs over his lower lip. He can still taste Anselm’s heavy, ruttish cologne on it.

Don’t go, he thinks.

As his thumb follows the line of that Teutonic chin and the

tendons on that strong Teutonic neck, the words are repeated in his head.

Don’t go.

Instead of opening the window, Charles continues his journey over the barrel of Anselm’s ribs, over the ridged iron of his belly. It is as if he is measuring his friend for a coffin.

‘Don’t go,’ he says, almost as a breath.

‘Can’t stay.’

Charles swings himself around fully now, so that he is sitting on the side of the bed, his feet on the floor. He stands, returns to the window and looks down at the lights and the circling traffic. ‘They’re going to find a safe place for him, somewhere in the Welsh countryside. That’s what I’ve heard anyway.’

‘Who?’

‘Eros.’ He turns his head towards the bed, his feet remaining where they are. ‘Such a depressing thought.’

‘What is?’

‘Eros leaving. London losing its libido. A sexless capital.’

‘Don’t be so fucking dramatic, Charles.’

‘We can go back to the Chelsea Arts Club soon. I just don’t think we should push our luck there.’

‘We are artists. They are artists. They understand.’

‘That’s as maybe, but there are limits to their tolerance.’ Charles turns his back to his friend again. It is easier this way. ‘In the new Germany they have already reached their limit.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘They don’t understand our sort.’

Anselm stiffens. ‘Says who?’

‘We are not welcome there.’

‘Speak for yourself.’

‘Anselm. Don’t be naïve.’

‘I’ll be careful. They need never know. And when the war is over I will come back here, get on the first bus to Gower Street, march into the Slade and ask if I can finish my degree. That is a promise. I will then wait for you in the Student Union bar.’

The rush of tenderness Charles feels at this moment makes him want to hold Anselm with such force that the two of them melt into one. But he remains standing by the window, still looking down, addressing his words to the road below. ‘As you did that first time.’