The Road Narrows As You Go (16 page)

Read The Road Narrows As You Go Online

Authors: Lee Henderson

For a moment the room fell totally silent, then erupted into unabashed mayhem. The entire room was up for grabs. Everything was being vandalized. Anything not bolted down got thrashed. Bits and pieces of the set flew through the air. A fusebox exploded and showered sparks over screaming fans. Vaughn Staedtler pointed to the exit and we grabbed Wendy and made it out in time to watch three cop cars and the paddywagon pull up out front, the cops brandishing clubs and storming the front doors of the Tool & Die.

Three hours later we had to go pick up Biz and Morphine Annie from the drunktank down at the Mission police station on Seventeenth; potential charges would follow, but for now the queens were free to go.

Thanks for the grand tour! Biz spat at the cops on the way out of the precinct, holding her high heels in her hands.

On the drive back to No Manors, Wendy parked at the coffee shop without a name where we drank strong Peruvian espresso as the sun came up and tried to make sense of what all had happened. Vaughn met us thereâ he drove some sleek black European two-seater with the steering wheel on the right-hand sideâand despite his advanced age seemed the most alert of all of us. We were bagged. Felt like we'd been up forever. Meanwhile he talked and talked, he went on some more about his doublecrossing assistants, about his avant-garde clowns, about drawing comics for the army newspaper in Korea for three years in a mobile newspaper office under a tent. Vaughn drew dozens and dozens of G.I. gags for an editor-slashcommanding officer who had no ear for humour and rejected anything he sketched that wasn't Sinophobic or a direct insult to the Communists. Using a felt marker he pinched off the barista, Vaughn scribbled charming portraits of us in

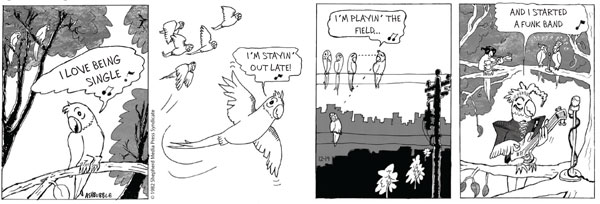

The Mischiefs

style, and one of Biz Aziz on stage from his point of view down in the audience.

You never needed no assistants anyway, Biz told him as she sipped her espresso. She plucked the drawing of her off the table and pushed it down the neckline of her dress. She winked at the old man. You're supertalented, Vee. You should get back in the funny pages.

Nah, he said and scratched the nape of his neck. I got my sights on the MoMA now.

Yeah and thanks again for picking us up, said Lil Morphine Annie, shivering and pale in her evening gown, clutching her broken wig on the floor between her ankles. Her voice was rawer than usual, she was coming down from an anxiety attack. I sure fucking hope SFPD got enough of a look to last them a while, because I for one don't plan on visiting

that

party again soon.

Vaughn's eyes were fixed on Biz. You ravished us from up there, under the spotlights, he told her. That's why the crowd went mad. It was a collective simultaneous orgasm.

That's my art, you see, to drive men mad.

That morning instead of driving home to feed his cats and sleep, or paint more clowns, Vaughn Staedtler stayed with Biz in her room on the third floor of No Manors and so began another of his wild affairs, and one of Biz Aziz's few intimacies.

STRAYS

13

Between the summer of eighty-one and the winter of eighty-two, Frank Fleecen's office underwrote Shepherd Media's purchase of more than thirty local and regional newspapers, and in the next few years, with the aid of still more junk bonds, Shepherd Media amassed a practical monopoly on cable affiliates and local papers south of the Mason-Dixon line. Most papers had an unspoken liberal-intellectual bias when Shepherd Media bought them, but that would soon be reversed to an openly conservative, tabloid slant. Through massive layoffs and minimal rehires, staffs were reshaped to suit the new agenda. Shepherd Media snapped up firesale presses on the brink of disaster, underwriting new business plans for small potatoes like the

Carbondale Gazette

and

Boonville Herald

; Macon, Marietta, and Alpharetta, Odessa and Fort Worth all had newspapers for sale, Gainesville and Enid etcetera. Shepherd Media's original loan was to the tune of fifteen million dollars, issued as part of Hexen's high-yield bonds, those

zabagliones

he'd bragged about. Then the loan doubled and tripled, it grew until Shepherd Media had borrowed up to a hundred million in bonds. Shepherd Media and

its sole owner, the middle-aged entrepreneur Piper Shepherd, had found a position as titan of industry.

Impressive, except it was on a line of credit in an industry many experts considered moribund. Every year the number of regional newspapers was shrinking. Local cable affiliates were shutting down one after another, too, went the story, as capital amalgamated and interests merged. Money was like beads of mercury in that way, money joined with money, money wanted to accumulate in one place, in the hands of one. Money was accumulating in Hexen Diamond Mistral to the tune of a two hundred million American dollars in eighty-one. The entire premise behind Shepherd Media's business plan was mocked by wiser competitors who saw smoke and mirrors. Piper Shepherd was derided on TV, portrayed as a southern gentleman of wealthy lineage with a charm school smile, the intellect of a shoe, family connections going back to the Civil War, and considering he was in his mid-fifties, the temper of a spoiled brat baby. More often than Shepherd Media, though, the journalists in New York preyed on Frank Fleecen and Hexen Diamond Mistral's high-yield bonds division, their strategies were openly criticized in op-eds invariably written by retired high-level employees of Hexen's competitors.

You can slap lipstick on a pig, went the line in the op-ed in the financial section of the

Washington Post

, but it's still Shepherd Media.

The unbuyable

New York Times

financial analyst wrote: Far from leading the sheep, Shepherd Media is clearly one of Frank Fleecen's most docile lambs, hypnotized by the Hexen Diamond Mistral chantâjunk junk junk junkâfollowing all his orders without question, even willing to stretch out on the chopping block, first to the slaughter come winter.

Meanwhile, down on the ground floor of this burgeoning empire, Gabrielle Scavalda's office had a window that looked out at pedestrians who used its reflective outer surface as a casual mirror to fix their hair and check their teeth and nose as they walked by, invariably while she was in a meeting. Once a man stuffed his hand down his pants and adjusted

himself while she tried to hold a conversation with a rival editor. It was in this office in upper Manhattan where she pushed her syndicate's travelling salesmen to make

Strays

their number one priority in meetings with local editors. A lot of her days were spent fielding calls and making calls. Not unlike Frank, her business was in her contacts, and at night she locked her Rolodex in a safe under her desk.

We heard Gabby's pitch so often we could recite it verbatim. She beat the greatness of

Strays

into us until we were convinced, not that we needed convincing. We were a sounding board. Quite often when she called the manor it wasn't just to share good news or ask for an update on a revision, she used us to complain about the indolence of her travelling salesmen. Now's the time to strongarm those editors to slot in

Strays

, she would tell them

,â

don't let them renew another syndicate's strip ⦠Yeah, I'm serious, Gabby would shout at So-and-so calling from a payphone in Dottie's Diner. What's the nearest newspaper? You're where? On Kilgore Road outside Toone? Okay, I know Toone. Listen, you go tell that rat Chuck Emerald at the

Toone Tribune

to bump

Sally Forth

. Save that stuff for

The New Yorker

, right? Okay I'm looking at my map â¦, Gabby would say. Tell them you finally found a note from the underground that isn't reprehensibly perverse. Say

Strays

is new wave but it's closer to

Peanuts

than to

Amy & Jordan

âsay that. Same goes for a paper like Paducah's

Examiner

. They don't need headscratchers either. Dump

Levy's Law

and subscribe to

Strays

and watch sales rise. Tell them the adventure strips are done.

Judge Parker

is dead weight. No one is reading sequentials anymore. A burg like Pinckneyville needs straight laughs and

Strays

delivers gags.

These were Gabby's words.

What we gleaned from Wendy and Gabrielle: The common newspaper comic strip salesman was a dark soul with wheels under him for a reason. So far no woman had been foolish enough to apply for this unprepossessing job. The travelling strip salesman worked for a syndicate on a meagre salary plus decent commission plus maybe monthly and annual

bonuses in the case of some outstanding sales. Each salesman was given a portfolio of strips to pitch and a map of America. Gas and car repairs were reimbursed, all other travel expenses including hotel were covered by a straight fifty-five-dollar per diem. Carrying a wagonload of demons and a surfeit of charm, they squandered their skills delivering hackwork to idolless editors, these men who could sell anything and chose to make a living off comics, who lived on the blacktop and raced against their own despair. These were strange, solemn, almost always solitary men with a string of cowardly divorces behind them or just as often actively polygamists. Comic strip salesmen were known to harbour multiple families across many states, some lived multiple lives, they were all a lurid, improbable secret the salesman was able to juggle. A gun in the glove compartment of course. For all intents and purposes living out of Fords and Chryslers, the salesmen drove for hours and hours every day across their patch of America and slept in motels off the highway. The hole opening up in front of them on the highway kept getting wider. Slowly going into debt. They only came to life on the jobâafter a shave and a shower, cup of coffee, and squared away inside a quality suit, tie knotted, the smile came out of hidingânow he was ready to sell a strip. Suddenly gregarious, outgoing, confident, and socially adept, the best comic strip salesman was the one who seemed completely indifferent to landing a new subscription but loved the chance to get to know a new friend or catch up with an old one. Friendships were key. The friendship was what counted, being pals, going for drinks, shooting the shit, bullshitting, and other shit; the businessâ after all, we're just talking comic strips hereâwas an afterthought, more gossip than art, more of an excuse to hang out than a business. Speaking of strips, listen, Emerald, I got a deuce burning a hole in my pocket, so if you don't mind looking at dancing girls, let's go have a beer.

Aided by Shepherd Media's near monopoly of newspapers in the southern states, and Frank Fleecen's diligent work selling

Strays

to businesses, we watched Wendy's subscriptions double, triple, then a

hundredfold increase in the span of a little more than twenty-four months. Every time she ripped open a paycheque it was for an even larger sum. An incredible list of cities and towns we had never heard of before, obscure place names whose locations confounded us even when searching across an open map. Yazoo City, Mississippi; Eggnog, Utah; Coin, Iowa. A subscription to

Strays

now cost a newspaper four dollars for every daily strip and seven twenty-five for a Sunday oversized colourâfifty cents above the going rate for strips like

Drabble

,

Broom-Hilda

, and

Geech

. After the split with syndicate and Hexen, Wendy's cut was down to a dollar and a quarter for a daily and about two-fifty for a Sunday, for every subscription, so do the math and at her peak from eighty-two to eighty-seven, when

Strays

was in more than a thousand newspapers across America and the rest of the world, that still adds up to a couple million dollars a year to play with. And that's before the cheques that came from Frank Fleecen's licences and merchandising.

Wendy found that in the months after Hick's death, she often woke up with a stiff jaw and sore teeth, and this persisted all summer. Her top and bottom molars felt locked together. Her temples pounded. Cold liquids gave her piercing pains throughout her entire mouth and sinuses, made her brain throb. In the fall she couldn't stand it anymore and went and saw Dr. Spencer, the dentist on Mission Street Biz went to, who told her her masseters were in knots, she was going to crack a crown if she didn't get some therapy. Therapy? Spencer also made an appointment for her to be fitted for a silicone mouthguard to wear at night for the rest of her life if she didn't seek deeper help, and recommended a Jungian hypnotist named Samantha Collins in Twin Peaks and wrote down the number.

Therapy

. She shivered from toes to scalp at the tantalizing thought.

She opened additional bank accounts with Solus First National Savings & Loans as time went on, to divide up her income streams and distribute money from each into investment pools elsewhere, and placing

a tiny percent of her income every month into an account set aside just for emergencies. But in fact these accounts were all opened at the suggestion of Frank Fleecen, who used Gabby as an intermediary to give advice of this kind. All these accounts were accessible to Frank through his numbered wire transfer account, and the ostensible reason was that he was her financial manager. Doug Chimney never blinked an eye after the first time. When the account set aside for Shepherd Media's paycheques cracked a million in November of eighty-two, Doug Chimney handled the deposit himself, rang a bell, all the tellers and the other clients in line applauded her fortunes, and back in his office he poured her a generous glass of Louis XIII to celebrate. According to the evidence from investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission, between 1981 and 1987, Wendy opened at least sixteen separate bank accounts at Solus First National, and Doug Chimney was fully aware of the extent to which her accounts were being used as operational funds for Frank Fleecen's most complicated deals. Whenever he saw Wendy come to make a deposit, in fact, Chimney was eager to open a few private safes in his office, let her try on the Roman Empire jewels and flip through the yellowed crinkled pages of his nearly priceless, certainly irreplaceable first edition of Hans Grimmelshausen's novel

Simplicius Simplicissimus

published in the year 1669. Then when she was drunk and pliable and floating on the vapours of brandy and the ego boost of all this wealth, he tried for more.