The Road to Berlin (90 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

On the morning of 16 October the two Baltic fronts and the 3rd Belorussian Front launched their several attacks. Lt.-Gen. Zakhvatayev’s 1st Shock Army on the right flank of Yeremenko’s 2nd Baltic Front made the best progress during the next few days, forcing the Lielupe and taking Kemery on 18 October, but on reaching the defensive positions covering Tukums 1st Shock Army was halted in its tracks. The offensive finally stalled in the face of heavy German resistance making great use of the marshes and bogs which abounded. Bagramyan’s attack along the ‘Liepaja axis’ also ran into sustained German resistance, where counter-attacks at full divisional strength supported by substantial numbers of tanks held off the Soviet armies. In spite of a further attempt late in October to burst through the German defences and deal the final blow to the trapped divisions, Bagramyan’s men could not manage it and this offensive inevitably came to a halt. Nor did Soviet troops succeed in rushing the defences at Memel. On the East Prussian frontier, Chernyakhovskii pressed home a powerful attack, penetrating two German defensive lines and capturing Goldap, only to bump into a third line running from Angerapp to Gumbinnen and on to Pilkallen. The way to the ‘Insterburg gap’ was barred except for a frontal assault on Gumbinnen or a

turning movement on Pilkallen. Both, for the moment, were impossible, and Chernyakhovskii’s attack also was called off at the end of October.

Memel held out until January 1945: the Courland divisions remained locked up in their peninsula, nothing but a wasting asset. Their war came to an end in May 1945, when they surrendered to the Red Army.

On 28 October 1944, having already surveyed the outcome of the gigantic offensive operations conducted by the Red Army during the summer and early autumn, senior officers of the Soviet General Staff in Moscow bent over their maps and pored over their calculations to complete the operational plan for the final campaign of the war, the Soviet invasion of Hitler’s

Reich

. This was the preparation of nothing less than the greatest campaign in military history, a campaign that was to unleash men in their millions and machines in their thousands, fusing massed battlefield efficiency with an elemental appetite for revenge, combining at the end cruel, unrelenting fighting with a rampage of almost animalistic fury. Behind the Soviet armies lay mile upon mile of stupefying ruination and the terrible, staggering weight of their own dead; ahead, at long last, ‘the lair of the Fascist beast’, the approaches to which were emblazoned with savage propaganda signs and slogans, designed to ravage the soldier’s memory with the evocation of past crimes committed by a now shuddering enemy on him and his own. From the top to the bottom, from the

Stavka

and the General Staff to the platoons and sections, the scent of the great kill sharpened with each day. ‘As before’, wrote a Soviet soldier towards the end of 1944, ‘I am on my way to Berlin … Berlin is precisely the place we

must

reach … we deserve the right to enter Berlin’. Stalin’s mind apparently ran on exactly the same lines. Within days, therefore, he nominated the Soviet field commander and selected the Front forces for the capture of Berlin. The task of ‘co-ordination’ (normally assigned to

Stavka

‘representatives’) he reserved exclusively for himself.

The balance sheet for the year’s operations proved to be more rewarding than the Soviet command’s own expectations. All the German army groups—North, Centre, North Ukraine (A) and South Ukraine (Group South)—had suffered drastic losses. The Red Army destroyed on Soviet calculations 96 divisions and 24 brigades (killed or captured), battering another 219 divisions and 22 brigades, of which 33 divisions and 17 brigades were so severely mauled that they were disbanded. On this reckoning the German armies in the east lost more than a million and a half men, 6,700 tanks, 28,000 guns and mortars, and over 12,000 aircraft; during the months of August, September and October the

Ostheer

suffered 672,000 casualties, receiving 201,000 men as replacements—cutting German strength in the east during this single three-month period by almost half a million men.

With the offensive unrolling across the entire arc from the Barents to the Black Sea, Soviet armies fought on not only their own territory but also on that of

eight foreign countries. The greatest depth of operations was reached in the ‘south-western theatre’ (south-eastern Europe), which stretched for 750 miles. The number of double envelopments increased—Vitebsk, Bobruisk, Minsk, Brody and Kishinev—with a marked reduction in the time taken for the elimination of the encircled divisions (which at Stalingrad lasted two months but at Kishinev not much more than five days and east of Minsk a week). Of all the German units knocked out during the years 1941–4, more than half (sixty-five per cent) were eliminated in the course of 1944. The scale of these operations also showed in the effort to maintain supplies to the fronts: in 1943 the central supply system delivered the equivalent of 1,164,000 million railway wagon loads, in 1944 the figure rose to 1,465,000 (of which 118,000 consisted of ammunition loads alone). The three services consumed almost 4 million tons of fuel (almost one-third of the entire wartime consumption) compared with 3.2 million tons in 1943. Production of weapons continued to climb towards the end of 1944, rising to the peak of almost 30,000 tanks and

SP

guns, together with 40,000 aircraft.

Save for Courland, the Soviet frontier was now everywhere restored. At the end of October, Soviet troops reached the northern frontier of Finland, with whom the Soviet Union formally signed an armistice on 19 September, and were pushing into northern Norway. With the Baltic states now virtually cleared, the Soviet advance reached into East Prussia itself as far as a line running from Goldap to Augusto, on the eastern and south-eastern borders. Somewhat to the south, Soviet armies established a number of bridgeheads on the Narew and the Vistula, the most important being Serock (2nd Belorussian) and three at Magnuszew, Pulawy and Sandomierz, held by the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts emplaced along the line of Praga (Warsaw)—the Vistula–Jaslo; in Hungary the 3rd Ukrainian Front was fighting on the outskirts of Budapest. The decisive zone of operations—that which contained the shortest direct route to Germany—lay between the Niemen and the Carpathians, but the whole slanting of the Soviet fronts at the end of October placed considerable strength to the north, with many armies deployed between the Niemen and the Gulf of Finland, and Meretskov’s army group committed between the Gulf of Finland and the Arctic Ocean. Of those Soviet army groups deployed along this shortest route (Chernyakhovskii’s 3rd Belorussian, Zakharov’s 2nd Belorussian, Rokossovskii’s 1st Belorussian and Koniev’s 1st Ukrainian Front), two—3rd and 2nd Belorussian—faced the formidable obstacle of East Prussia. They required reinforcement, but time was needed to redeploy them in the ‘northern zone’ even though the surrender of Finland and the reduction of the Baltic states released several armies to join the Niemen-Carpathians concentration. It was not simply a question of storming on into the

Reich

, or even of redeploying: the whole balance of the eastern front had to be taken into consideration.

At first sight, a thrust straight through East Prussia seemed to offer the most favourable opportunity, not least because the 3rd Belorussian Front outnumbered the enemy, with 40 Soviet infantry divisions to the German army’s 11, 2 Soviet

armoured corps to 2

Panzer

divisions, in all 17 German formations against 47 Soviet formations. The General Staff submitted, therefore, that with reinforcement from

Stavka

reserves it might be possible to drive in strength through East Prussia to a depth of over 150 miles, on to the mouth of the Vistula. On closer inspection, this proved to be much too optimistic, since in the first instance Soviet superiority melted away in comparing divisional strengths (a German infantry division disposed of greater strength than its Soviet counterpart and a Soviet armoured corps was virtually the equivalent of a

Panzer

division). As for the ‘Warsaw–Poznan axis’ and the ‘Silesian axis’, where the ‘battle for Berlin’ was to be decided, the Soviet General Staff anticipated very heavy resistance. They calculated that even with maximum effort, the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts could drive only as deep as 90–100 miles.

There remained yet another radical alternative—to use the ‘southern’ fronts, 4th, 3rd and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts, in a deep penetration aimed at the

Reich

, passing through Budapest, Bratislava and Vienna. In Rumania enemy armies had been dispersed and destroyed, while war-weary Hungarian divisions (as they were depicted by Soviet intelligence) formed a large part of the defending force in Hungary, the ‘breakwater’ of the

Reich

. The events of mid-October in Hungary dispelled that illusion: Hungary was held tight within the German grip, the fighting for Budapest took a desperate turn, and by the end of October the Soviet command reckoned with the presence of thirty-nine enemy formations in action against Malinovskii’s 2nd Ukrainian Front battling at the approaches to Budapest, and on a 350-mile front running from Miskolcz in the north to Subotica in the south.

The Soviet General Staff could not ignore the fact that the Soviet offensive was slowly running down. It was time to give the divisions some respite, to regroup, to reorganize the supply and rear services, and to build up reserves of men and weapons to ensure that the coming breakthrough operations could be successfully carried through. Marshal Zhukov and Marshal Rokossovskii on the 1st Belorussian Front put these points plainly to Stalin towards the end of October: the offensive operations between Seroch, Modlin and Praga entrusted to the 47th and 70th Armies were producing no results at all, except for inflicting heavy casualties on the tired and depleted Soviet armies. Perkhorovich’s 47th was fighting under orders from the

Stavka

to reach the Vistula between Warsaw and Modlin, with instructions to expand the bridgeheads on the river Narew. Zhukov could see no point whatsoever in these fruitless and exhausting operations. Stalin, however, was not so persuaded, and when the two Soviet commanders reported to him personally in Moscow he suggested armoured and aviation reinforcement for 47th Army to ram it on to the Vistula. Though Molotov bleated about stopping a successful offensive, Zhukov pointed out that the Germans were clearly holding up the Soviet advance and insisted to Stalin that ‘our offensive will yield us nothing but casualties’. Zhukov then continued with a typical strategic résumé that went to the heart of the matter—the Soviet armies did not need the area

north-west of Warsaw; the city must be turned from the south-west, and at the same time ‘a powerful splitting blow’ must be delivered in the direction of Lodz-Poznan. This would inevitably smash in the German Vistula Front and open the way for deep penetrations by Soviet mobile columns. After ushering out Zhukov and Rokossovski, urging them ‘to think some more’, Stalin recalled them after twenty minutes and informed them that Soviet forces would go over to the defensive: as for future plans, these would be discussed later. The next day Stalin consulted Zhukov on another matter, asking whether the fronts could be controlled directly from the

Stavka

(without the use of ‘co-ordinators’ such as Zhukov himself or Marshal Vasilevskii). Zhukov agreed that the smaller number of operational fronts and the shortening of the front as a whole made this quite feasible. That evening Stalin telephoned Zhukov to inform him that the 1st Belorussian Front would be operating in what he called ‘the Berlin strategic zone’ and that he, Zhukov, would assume command of the front. Zhukov agreed.

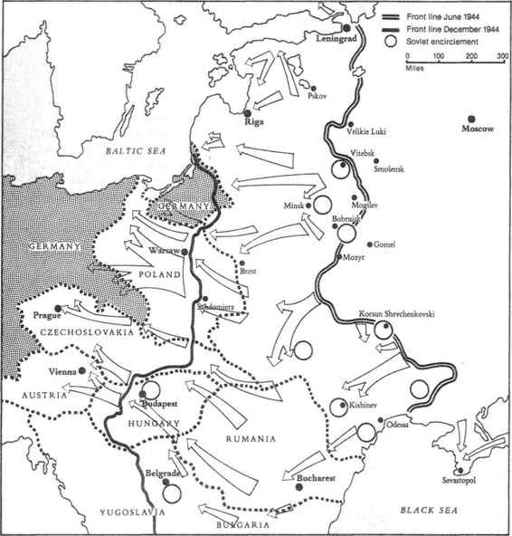

Map 12

Overall Soviet offensive operations in eastern Europe, 1944

At the beginning of November the three Belorussian fronts (1st, 2nd and 3rd) were obliged to turn to the defensive in ‘the entire western zone of operations’. General Antonov of the General Staff and Shtemenko at the head of Operations along with A.A. Gryzlov and N.A. Lomov (the officers responsible for planning particular strategic axes) now elaborated the draft plan for submission to Stalin and the

Stavka

. In line with what had now become standard procedure, this draft plan concentrated on the initial phases of the offensive and simply sketched in subsequent Front assignments. The broad outlines derived from an ‘all-round assessment of the situation and capabilities of all the combatants’, Allied and Axis: at this point the Red Army in the east and the Allied armies in the west stood roughly the same distance from Berlin, with 74 German divisions in the west, supported by 1,600 tanks, facing 87 Allied divisions and over 6,000 tanks, while in the east the German command retained over 3 million men, about 4,000 tanks and 2,000 aircraft. With such a balance sheet before them, the Soviet planners drew some obvious conclusions about the ‘race for Berlin’. Clearly, for the Red Army the ‘central sector’ (or the ‘western zone’) was of decisive importance, providing the most direct route into Germany. But here the German armies must offer the stiffest resistance. To weaken this German concentration at the centre, the Red Army would have to operate with maximum effectiveness on the flanks, involving not only Hungary and Austria but also East Prussia. In brief, a powerful thrust into Budapest and against Vienna meant a simultaneous attack on Königsberg, thus draining German strength away from the ‘western axis’.