The Roughest Riders (22 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

They were progressing slowly through the shrubbery and stands of small trees when Roosevelt experienced his fourth close encounter. A bullet from the hill clipped his elbow, drawing a copious flow of blood, and a couple of bullets grazed Texas without doing serious damage. Roosevelt patched up his wound with his neckerchief and soldiered on.

The troops climbed slowly, struggling, some dropping to their stomachs to fire a few rounds of their own now and then. Some of the men criticized the Spaniards for hiding behind barricades while the Americans were easy targets, with nowhere to find good cover.

The uphill assault toward Kettle Hill dragged on for twenty more minutes before the Tenth discovered another strand of wire strewn through the brush. This time they could not pull it down quickly enough to help the men behind them, and Texas stumbled right into it, cutting a deep gash across his chest and forelegs,

drawing him up short. The horse was badly wounded and could go no farther. Roosevelt dismounted, checked out the injury, and handed the reins to one of his men. From that point on, he had to proceed on foot like the others.

They were now within three hundred yards of the crest and could make out the Spanish flag at the top for the first time. The sight of the ensign seemed to invigorate the troops and propel them upward at a faster pace. To everyone's surprise, they found there was a lower ridge protruding from the hill about one hundred yards below the peak of Kettle Hill, a feature that had previously gone unnoticed. This, according to military strategists, would have been the so-called military crest, the ridgeline that should have been the Spaniards' first line of defense. Compared to the geographical crest, it would have provided them with an even better vantage point over the American attackers and the entire field of combat. General Linares, however, had determined earlier that his heavily outnumbered forces stood little chance of ultimate victory against such overwhelming odds, and, realist that he was, had positioned his troops for retreat. Having expected the main line of assault to be at Santiago, he had ordered his five hundred or so defenders to the top of the hill, to be better prepared for an eventual withdrawal when the Americans finally, inevitably, overran his positions.

Buffalo Soldiers with Sumner's Ninth and Pershing's Tenth rushed ahead first, one of the men in the Tenth carrying his unit's guidon as they ascended to within fifty yards of the peak. They were whooping and yelling, the taste of victory in their mouths as they closed in on the enemy entrenchments. “By God, there go our boys up the hill! Yes, up the hill!” one of the troops yelled out, astonished. A moment earlier, it had appeared that they would all be cut down.

The cries of impending victory grew louder as they charged ahead, with most of Roosevelt's remaining Rough Riders now

beside the Buffalo Soldiers. Roosevelt was startled when a disoriented Spanish bugler, attempting to run away, ran into his arms instead and was taken prisoner. The yelling intensified when the first rank of Americans saw the Spaniards leaving their trenches and streaming southwest toward San Juan Hill, some returning fire as they ran, but most intent on avoiding the newly energized American army. The soldiers of the Tenth planted their guidon on the hill as the troops swarmed across the crest, with a clear view of the retreating defenders heading down the back slope in the direction of San Juan Hill. Roosevelt later claimed that the Rough Riders had planted their standard first, but one of his Rough Riders, Nova Johnson from New Mexico, said later, “You should have seen the amazement Colonel Teddy's face took on when he reached the top of that first ridge, only to find that the colored troopers had beat us up there.”

“That day we fought pretty hard and my gun became so hot I could hardly hold it,” wrote C. D. Kirby with the Ninth in a letter to his mother. “The soldiers were falling all around me and I thought every minute would be my time.” Kirby shot and killed two Spanish snipers hidden in their perches on nearby trees.

“We had a hard fight,” wrote Sergeant Bivins of the Tenth. “Our loss is very heavyâ¦. I got hit myself and was stunned for five minutesâ¦. Bravery was displayed by all of the colored regiments. The officers and reporters of other powers said they had heard of the colored man's fighting qualities, but did not think that they could do such work as they had witnessed.”

One of the Rough Riders, Frank Knox, who would go on to become secretary of the navy during World War II, wrote afterward, “I joined a troop of the Tenth Cavalry, and for a time fought with them shoulder to shoulder[,] and in justice to the colored race I must say that I never saw braver men anywhere. Some of those who rushed up the hill will live in my memory forever.”

A reporter with the

New York Mail and Express

headlined his article A

LL

H

ONOR TO THE

G

ALLANT

T

ROOPERS OF THE

B

LACK

T

ENTH

. He reported that they fired “as they marched, their aim was splendid, their coolness was superb, and their courage aroused the admiration of their comrades. Their advance was greeted by wild cheers

from the white regiments, and with answering shouts they pressed onward over the trenches they had taken close in pursuit of the retreating enemy. The war has not shown greater heroism.”

The black Ninth Cavalry was particularly effective during the battle for Kettle Hill, earning the accolades of American commanders and war correspondents, who said they had never seen men fight more bravely.

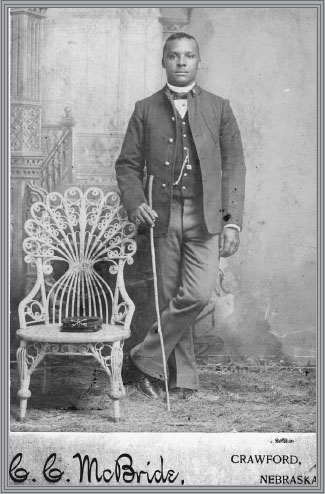

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-DIG-ppmsca-11342)

Another account of the battle, which appeared in the

New York Sun

, bestowed similar accolades on Sumner's Ninth. “The Spaniards, pouring shot into them at a lively rate, could no more stop the advance than they could have stopped an avalancheâ¦. The enthusiasm of the Ninth Cavalry was at its highest pitch and so it was with the other troops. Only annihilation could drive them back; the Spaniards could not.”

With the Buffalo Soldiers' guidon waving prominently on top of the hill, the Americans paused a moment and looked to the south. They were too exhausted after the arduous climb to pursue the retreating Spaniards, but from their vantage point on the peak, they had a clear view of the action that was still going on in the Heights. As bloody as the battle for Kettle Hill had been, the war was not yet over. Other violent encounters still lay aheadâthe campaign to overtake San Juan Hill and, finally, the conquest of the primary Spanish defense around the city of Santiago de Cuba.

T

o the south, Kent led the march on San Juan Hill with three brigades, a little more than five thousand men in all. Three officers marched with Kent, each in command of one of the brigades: General Hamilton Hawkins with roughly two thousand men in the First Brigade; Colonel E. P. Pearson commanding about fifteen hundred troops in the Second Brigade; and Colonel Charles A. Wikoff leading another fifteen hundred in the Third Brigade, including 534 with the black Twenty-Fourth Infantry. The Spanish had strung three lines of barbed wire along the foothills leading up to San Juan, beyond which lay three hundred yards of open mead-owland that offered no protection as the men tried to cross it.

A Spanish blockhouse dominated the peak of San Juan, which was the highest hill in the region. Wikoff's Twenty-Fourth moved ahead on the path to the left and took the lead as the Spanish defenders poured a heavy fusillade down along the trails leading to their positions. The Twenty-Fourth pushed slowly through the ranks of the other troops on the trail. The Ninth, the Tenth, and the Rough Riders to the north tried to descend the slope of Kettle Hill and join them, but they found themselves in range of the Spanish guns on

San Juan, which forced them to take cover where they could find it. The Spaniards were far fewer in number, but they still controlled the approaches to their trenches and barricades from the top of San Juan. A battery of two mountain guns, plus troops from the First Provisional Battalion of Puerto Rico, the First Talavera Peninsula Battalion, and a unit of sailors from the harbor, were sent up from Santiago to reinforce their defenses. General Linares also arrived on the scene and joined his men near the blockhouse.

Shells from the mountain guns now began to soar down on the American attackers trying to climb the hill. Linares had also sent up additional ammunition for the riflemen, who kept up a steady rain of fire from the blockhouse, trenches, and rifle pits. Below the crest of San Juan, the barbed wire fences zigzagged across the trails and through the brush on the slope of the hill. The east side of San Juan Hill was particularly steep, presenting more difficult terrain for Kent's men to traverse with their ranks strewn out for a mile or more to the rear. The cries of victory emanating from Kettle Hill suddenly seemed premature to the three brigades struggling in their own theater of the battle.

The three hundred yards of open space beyond the wire fences appeared more and more like an invitation into a slaughterhouse. It was a veritable killing field, with anyone entering it offering himself as an easy target for the Spanish marksmen. The Buffalo Soldiers of the Twenty-Fourth sliced through the barbed wire fences with their bayonets and rushed into the meadow first from the left, with shells and Mauser bullets falling all around them. The number of American casualties grew rapidly, among them Colonel Wikoff, who fell as he led the Twenty-Fourth and the rest of the Third Brigade into the open.

His death was witnessed by First Lieutenant Wendell Simpson, who stood beside him when it happened. “The first line upon reaching a slight ridge in the field, one hundred yards from the

creek bank, took position lying down and was rapidly joined by other lines in succession,” Simpson reported. “The second battalion pushed promptly forward, prolonging the line to the left. A terrific fire was continually poured from the entire line upon the works on top of the hill in frontâFort San Juan. It was just at this stage of the action that Colonel Wikoff received a bullet wound through the chest from side to side, which caused his death.”

The fifty-one-year-old Wikoff was the most senior-ranking American officer to die in action against the Spanish. He lingered about fifteen minutes before succumbing to the wound. Two regimental commanders behind him were also shot dead. Kent sent messengers back to Shafter for detailed instructions on what course of action to take from that point on. Precious minutes passed by with no word from the general's camp.

The commanders in the field decided it was time to take matters into their own hands. Kent met with Sumner and Wood, and together they decided that “the Heights must be taken at all costs.” There could be no turning back. They dispatched couriers to the regimental commanders with the message that a full-blown assault on San Juan Hill was the only option left for themâeither that or an unthinkable retreat back down the various trails leading to the coast. Onward and upward was the only acceptable decision for them.

At around the same time, the troops in the rear had managed to push the four Gatling guns farther along the trail and maneuvered them to within seven hundred yards of San Juan Hill. As soon as they were in position, the men fired the guns, which boomed like thunder and echoed across the hills. The American troops in the lead were startled at first, believing they had come under a new line

of fire from Spanish artillery behind them. Once they saw the detonations on the peak of San Juan, however, they shouted jubilantly, “It's the Gatlings, it's the Gatlings!” They rose to their feet to get a clearer view and could see that the American shells were hitting the enemy fortifications with great accuracy.

To the north on Kettle Hill, the Ninth, the Tenth, and the Rough Riders were also thrilled by the turn of events. The American big guns were taking a toll on the blockhouse and gun pits. The Spaniards lifted their heads above their barricades to get off some rounds, presenting easier targets for the Buffalo Soldiers and others on Kettle Hill, who fired at will as the enemy's attack began to subside. The Gatlings fired round after round for almost ten minutes straight, sweeping the peak of San Juan and the trenches around it with a ceaseless outpouring of devastating firepower. The Twenty-Fourth moved forward across the meadow, which gave way to a sharp incline three hundred yards away, where the base of the hill rose out of the valley floor. Lieutenant Jules G. Ord with Kent's First Brigade screamed out, “Come on! We can't stop here! I will not ask for volunteers, I will not give permission, and I will not refuse it! God Bless you and good luck!”