The Roughest Riders (30 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

It was a dark hour for US military might in more ways than one. Victories were sporadic at best and hard to achieve. The Filipinos were fighting on familiar turf in their homeland and outnumbered this latest group of imperialists who were determined to deprive them of self-rule. And their hit-and-run, guerrilla style of fighting was both effective and frustrating. When their bullets ran out, they dashed out from the bushes and attacked the American troops with machetes, bolos, and other primitive weapons, inflicting telling casualties before they disappeared back into the jungle.

Even before the war ended, elements of the US government began to look into allegations of war crimes committed by troops in the field. Forty-four separate trials were launched before March 1901, many culminating in convictions for the murder of civilians, rape, the razing of villages, and other crimesâalthough many of the more severe sentences were later reduced or commuted to fines by Roosevelt after he became president.

“I deprecate this war, this slaughter of our own boys and of the Filipinos,” General Felix A. Reeve was moved to write, “because it seems to me that we are doing something that is contrary to our principles.”

But the trials and entreaties fell on the deaf ears of some of the commanders in the field, who grew increasingly incensed by the heavy losses inflicted by the insurrectos. After a devastating defeat on Samar, an island south of Luzon, Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith roared to one of his majors, Littleton W. T. Waller, “I want no prisoners! I wish you to kill and burn! The more you kill and burn the better you will please me!” He added that he wanted to turn Samar into a “howling wilderness” following the deaths of fifty-nine American soldiers and twenty-three others wounded by insurrectos disguised as women. Smith left no doubts about his orders, saying he demanded the execution of all Filipinos more than ten years of age. The major carried out his orders and earned the sobriquet “the Butcher of Samar” for his efforts. After the court-martial that followed, Smith was “admonished” for his action, and Waller was acquitted of all charges.

During the 1902 Senate hearings in the wake of the war, Senator Joseph Rawlins asked General Robert P. Hughes, who commanded many of the campaigns, about the morality of burning villages and killing women and children. “The women and children are part of the family,” the general responded, “and where you wish to inflict punishment you can punish the man probably worse in that way than in any other. These people are not civilized.” Hughes added that the Buffalo Soldiers were somewhat to blame for the developments of the campaign in the Philippines: “The darky troops ⦠sent to Samar mixed with the natives at once. Wherever they came together they became great friends. When I withdrew the darky company from Santa Rita I was told that the natives even shed tears for their going away.”

So, the Buffalo Soldiers were damned if they did and damned if they didn't. After fighting valiantly in the Philippines against the backdrop of widespread criticism from the black community at large, they were then used as scapegoats by the very commanders who ordered them to violate the tenets of “civilized warfare.”

N

o war lasts forever, and the war in the Philippines was no exception. One by one, the insurrecto leaders surrendered to US troops. The capture of Aquino on March 23, 1901, at his house in Palanan, on the coast northeast of Manila, marked the beginning of the end of the insurgency. Twenty of his followers stood guard outside at about 3:00

PM

, when Aquino heard shooting in his courtyard. “Not suspecting any plan against myself,” Aquino wrote in a memoir, “I thought it was a salute with blank cartridges.”

He ran to a window and told his men to cease firing, but when he saw that an attacking party was aiming bullets in his direction, he ran to an inner room and grabbed his revolver. He was about to race back and defend himself against the Americans, but he was restrained by subordinates who told him not to sacrifice himself because “the country needs your life.” Four hundred US troops surrounded the house, killing and capturing Aquino's men. Five high-ranking officers entered his home. “Which one of you is Aguinaldo?” one of them asked. Aquino was then put under arrest by the five American officers leading the invasion force.

After a long, bruising campaign that tested American military strength to the limits, the war in the Philippines effectively drew to an end with the capture of the insurgents' leader in March 1901.

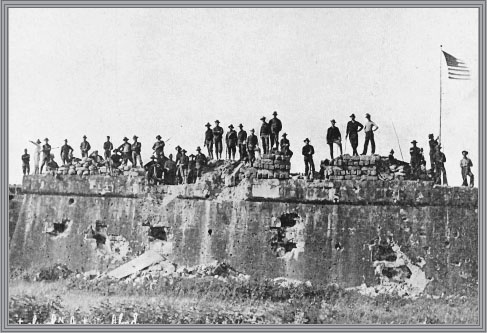

Commons.Wikimedia.Org

With Aquino's capture and the adoption of what amounted to war crimes tactics by military commanders in the field, the only unanswered question regarding the final fall of the Spanish empire was when it would happen. The hostilities continued for the rest of the year, but by 1902 the war essentially ended with the adoption of the Philippine Organic Act, passed by the US Congress on July 1. The law called for the establishment of an interim government along with the cessation of the insurrection, the completion of a census throughout the islands, and official recognition of the authority of the US government over the Philippines.

For many of the Buffalo Soldiers, however, the war would drag on long after most of the troops had returned home. Hot spots erupted in different regions throughout the islands, and the US

government assigned the men of the Twenty-Fourth the task of putting down the mini-rebellions where they occurred, mostly in the Muslim districts in the south. For the next four years, the Buffalo Soldiers and members of a new Philippine constabulary killed more than fifty insurgents who refused to submit to US rule. The Filipinos were now “our little brown brothers,” a term coined by William Howard Taft, the first American governor-general of the Philippines, who was elected the twenty-seventh president of the United States in 1908. But the white officers overseeing the mopping-up operations made no distinction between the Filipinos and the Buffalo Soldiers who remained abroad. They were all “niggers” as far as the officers were concerned. A popular song of the period captured their attitude clearly: “You are told he is your little brown brother, / and the equal of thee and thine. / Well, he may be a brother of yours, Bill Taft, / but he is no relation of mine.”

The Buffalo Soldiers who did return to their homeland after the conclusion of the major campaigns passed through the San Francisco Presidio in 1902 before departing for other assignments. Four men of the Ninth remained there until 1904, becoming the first black troops ever garrisoned at the Presidio on regular duty. In May 1903, Captain Charles Young, the third African American graduate of West Point and the only black officer authorized to lead men in combat, left with a contingent of troops from the Ninth and Tenth. His mission was to patrol the national parks at Yosemite, Sequoia, King's Canyon, and other locations, and “to establish a camp with the purpose of protecting the park from injury and depravations.” Young was a prominent hero of the action in the Philippines, spearheading attacks against the insurrectos in Samar, Blanca Aurora, Durago, Tobaco, and Rosano for a year and a half with the simple command, “Follow me!”

When an assassin's bullet claimed McKinley's life on September 14, 1901, Roosevelt succeeded him as president. The leader of the

Rough Riders toured California from May 12 through 14, 1903, and Young and his men flanked both sides of his carriage as the president rode down Market Street in San Francisco. It was a reunion of sorts between Roosevelt and the Buffalo Soldiers, who had last seen one another during combat on the hills in Cuba. Roosevelt's selection of them as his “Guard of Honor” was viewed by some as an apology for his disparaging remarks after the historic war.

Roosevelt followed this event with an invitation in 1904 to have black educator Booker T. Washington dine with him at the White Houseâthe first time an African American appeared there as a guest of honor. But he undid the goodwill he earned with the black community two years later when he summarily dismissed 167 Buffalo Soldiers following a shooting spree in Brownsville, Texas, that ended with the death of a white bartender and the wounding of a police officer. The War Department had actually precipitated the problem several months earlier, in May 1906, when it sent two battalions of the Twenty-Fifth to military bases in TexasâFort McIntosh and Fort Brown. The army criticized the order, knowing that the locals in Brownsville were particularly bigoted against black people.

“Citizens of Brownsville entertain race hatred to an extreme degree,” the white commander of the Texas National Guard had warned. Black chaplain Theophilus Steward had accurately predicted that “Texas, I fear, means a quasi-battle ground for the Twenty-Fifth Infantry.” Upon their arrival, the Buffalo Soldiers were greeted by signs banning African Americans from stores, restaurants, bars, parks, and other public facilities.

By the end of July, the tension in town was reaching the breaking point. Not allowed to drink in Brownsville's white-only bars, the Buffalo Soldiers set up a tavern of their own, which promptly became a favorite hangout for the men. Fights broke out between whites and blacks on several occasions, and it all came to a boil on the night of August 13. Around midnight, a group of about twenty

men gathered on Cowen Alley and started to shoot into buildings on both sides of the narrow passageway. Near the intersection of the alley and Thirteenth Street, a gunshot wounded a police officer, and then a half block farther along, bullets fired into a saloon killed the bartender inside.

The white officers at Fort Brown insisted that the black troops were in their barracks at the time of the incident, which came to be known as both the Brownsville Affair and the Brownsville Raid. The mayor and some prominent white locals, however, maintained that they had seen black soldiers firing guns indiscriminately at the time, and the army and the president were quick to use the Buffalo Soldiers as scapegoats. None of those dishonorably discharged, which included many longtime regulars with distinguished careersâsix of them Medal of Honor recipientsâwere tried and found guilty of the crime, yet their dismissal from the military cost them their pensions and other benefits.

In the aftermath of the shooting, investigators discovered spent cartridges and clips strewn throughout the street. Roosevelt referred to the men of the Twenty-Fifth as “bloody butchers” who “ought to be hung,” even though none of the bullets recovered were fired from the rifles of the black troops, according to white senator Joseph P. Foraker, who believed that local townspeople committed the crimes during a night of revelry.

The man who came to dinner two years earlier, Booker T. Washington, intervened on behalf of the black soldiers and pleaded with Roosevelt to reverse himself on the grounds that the evidence was inconclusive. The president denied his request, and a 1908 US Senate Military Affairs Committee hearing endorsed Roosevelt's decision. The Buffalo Soldiers of the Twenty-Fifth would have to wait another sixty-four years for vindication, when the army reopened the case and found the men innocent in 1972. The soldiers who were deceased received honorable discharges posthumously without

back pay for their families. One of two survivors, and the last man standing, Private Dorsie Willis, eventually got a check for $25,000 and was honored at ceremonies in the nation's capital and Los Angeles in 1973. “It was a frame-up straight through,” Willis said. “They checked our rifles and they hadn't been fired.” He died in 1977 at ninety-one years of age, outliving everyone who had rigged the case against him and his fellow soldiers.

In 1907, Congress moved to discharge all black troops from military service, but the effort went down in defeat. Instead, the army attempted to make amends for the framing of black soldiers in Brownsville by allowing more African Americans to enter West Point for cavalry training and instructions in mounted combat. As it turned out, the armyâand, increasingly, the navyâneeded black warriors for ongoing eruptions in the Philippines, where they dispatched the Twenty-Fifth again to put down uprisings by Moro tribesmen in 1907 and 1908.