The Rule of Four (16 page)

“How difficult is the

Hypnerotomachia

? Consider how its translators have fared. The first French translator condensed the opening sentence, which was originally more than seventy words long, into less than a dozen. Robert Dallington, a contemporary of Shakespeare’s who attempted a closer translation, simply despaired. He gave up before he was halfway through. No English translation has been attempted since. Western intellectuals have considered the book a byword for obscurity almost since it was published. Rabelais made fun of it. Castiglione warned Renaissance men not to speak like Poliphilo when wooing women.

“Why, then, is it so difficult to understand? Because it contains not only Latin and Italian, but also Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Chaldean, and Egyptian hieroglyphics. The author wrote in several of them at once, sometimes interchangeably. When those languages were not enough, he invented words of his own.

“In addition, there are mysteries surrounding the book. To begin with, until very recently no one knew who wrote it. The secret of the author’s identity was so closely guarded that not even the great Aldus himself, its publisher, knew who’d composed his most famous work. One of the

Hypnerotomachia

’s editors wrote an introduction to it in which he asks the Muses to reveal the author’s name. The Muses refuse. They explain that ‘it is better to be cautious, to keep divine things from being devoured by vengeful jealousy.’

“My question to you, then, is this: Why would the author have gone to such trouble if he were writing nothing more than a bucolic romance? Why so many languages? Why two hundred pages on architecture? Why eighteen pages on a temple of Venus, or twelve on an underwater labyrinth? Why fifty on a pyramid? Or another hundred and forty on gems and metals, ballet and music, food and table settings, flora and fauna?

“Perhaps more important, what Roman could have learned so much about so many subjects, mastered so many languages, and convinced the greatest printer in Italy to publish his mysterious book without so much as mentioning his name?

“Above all, what were the ‘divine things’ alluded to in the introduction, which the Muses refused to divulge? What was the vengeful jealousy they feared these things might inspire?

“The answer is that this is no romance. The author must have intended something else—something that we scholars have as yet failed to understand. But where do we begin searching for it?

“I do not intend to answer that question for you. Instead, I will leave you with a puzzle of your own to muse over. Solve this, and you are one step closer to understanding what the

Hypnerotomachia

means.”

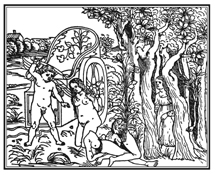

With that, Taft triggers the slide machine with a pump of his palm on the remote. Three images appear over the screen, disarming in their stark black and white.

“These are three prints from the

Hypnerotomachia,

depicting a nightmare that Polia suffers late in the story. As she relates, the first shows a child riding a burning chariot into a forest, drawn by two naked women whom he whips like beasts. Polia looks on from her hiding place in the woods.

“The second print shows the child releasing the women by slicing their red-hot chains with an iron sword. He then thrusts the sword through each of them, and once they are dead, he dismembers them.

“In the final print, the child has torn out the still-beating hearts of the two women from their corpses and fed them to birds of prey. The innards he feeds to eagles. Then, after quartering the bodies, he throws the rest to the dogs, wolves, and lions that have gathered about.

“When Polia awakens from this dream, her nurse explains that the child is Cupid, and that the women were young maidens who offended him by refusing the affections of their suitors. Polia deduces that she has been wrong to rebuff Poliphilo.”

Taft pauses, turning his back to the audience in order to contemplate the enormous images that seem to float in the air at his back.

“But what if we suppose that the explicit meaning is not the

real

meaning?” he says, his back still to us, in a disembodied voice that resonates through the microphone on his chest. “What if the nurse’s interpretation of the dream is not, in fact, the right one? What if we were to use the punishment inflicted on these women to decipher what their crime truly was?

“Consider a legal punishment for high treason that survived among certain European nations for centuries before and after the

Hypnerotomachia

was written. A criminal convicted of high treason was first

drawn

—meaning that he was tied to the tail of a horse and dragged across the ground through the city. He was brought in this way to the gallows, where he was hanged until he was not fully dead, but only half-dead. At this time he was cut down, and the entrails were sliced from his body and burned before him by the executioner. His heart was removed and displayed to the assembled crowd. The executioner then decapitated the carcass, quartered the remains, and displayed the pieces on pikes in public locations, to serve as a deterrent to future traitors.”

Taft returns his focus to the audience as he says this, to see its reaction. Now he circles back toward the slides.

“With this in mind, let us reconsider our pictures. We see that many of the details correspond to the punishment I’ve just described. The victims are drawn to the location of their deaths—or rather, perhaps a bit ironically, they draw the executioner’s chariot themselves. They are dismembered, and their limbs are shown to the assembled crowd, which in this instance consists of wild animals.

“Instead of being hanged, however, the women are slain with a sword. What are we to make of this? One possible explanation is that beheading, either by ax or sword, was a punishment reserved for those of high rank, for whom hanging was deemed too base. Perhaps, then, we may infer that these were ladies of distinction.

“Finally, the animals that appear in the crowd will remind many of you of the three beasts from the opening canto of Dante’s ‘Inferno,’ or the sixth verse of Jeremiah.” Taft looks out across the lecture hall.

“I was just about to say that . . .” Gil whispers with a smile.

To my surprise, Charlie hushes him.

“The lion signifies the sin of pride,” Taft goes on. “And the wolf represents covetousness. These are the vices of a high traitor—a Satan or a Judas—just as the punishment seems to suggest. But here the

Hypnerotomachia

diverges: Dante’s third beast is a leopard, representing lust. Yet Francesco Colonna includes a dog instead of a leopard, suggesting that lust was

not

one of the sins for which the two women are being punished.”

Taft pauses, letting the audience chew on this for a moment.

“What we are beginning to read, then,” he begins again, “is the vocabulary of cruelty. Despite what many of you may think, it is not a purely barbaric language. Like all of our rituals, it is rich with meaning. You must simply learn to read it. I will therefore offer one additional piece of information, which you may use in interpreting the image—then I will pose a question, and leave the rest to you.

“Your final clue is a fact that many of you probably know, but have overlooked: namely, that we can tell Polia has misidentified the child, simply by noting the weapon the child is carrying. For if the little boy in the nightmare had truly been Cupid, as Polia claims, then his weapon would not have been the sword. It would have been the bow and arrow.”

There are murmurs of assent in the crowd, hundreds of students seeing Valentine’s Day in an entirely new light.

“Therefore I ask you: who is this child that brandishes a sword, forces women to draw his war chariot through a difficult forest, then slaughters them as if they were guilty of treason?”

He waits, as if preparing to deliver the answer, but instead says, “Solve this, and you will begin to understand the hidden truth of the

Hypnerotomachia.

Perhaps you will also begin to understand the significance not only of death, but of the form death takes when it comes. All of us—we of faith and we who lack it—are too accustomed to the sign of the cross to understand the significance of the crucifix. But religion, Christianity in particular, has always been the story of death in the midst of life, of sacrifices and martyrs. Tonight, of all nights, as we commemorate the sacrifice of the most famous of those martyrs, it is a fact we should be loath to forget.”

Removing his glasses, and folding them into his breast pocket, Taft tips his head and says, “I entrust you with this, and place my faith in

you.

” With a plodding step back, he adds, “Thank you all, and good night.”

Applause erupts from every corner of the hall—at first awkwardly, but soon to a heavy crescendo. Despite the earlier interruption, the audience has been seduced by this strange man, mesmerized by his fusion of intellect and gore.

Taft nods his head and shuffles toward the table by the podium, meaning to sit down, but the applause continues. Some in the audience take to their feet, continuing to clap.

“Thank you,” he says again, still standing, hands pressed atop the back of his chair. Even as he speaks, the old smile returns to his features. It’s as if he has been watching the audience all along, never the other way around.

Professor Henderson rises and strides toward the lectern, silencing the applause.

“By tradition,” she says, “we will be offering refreshments this evening in the courtyard between this auditorium and the chapel. I understand that the maintenance and ground crews have set up a number of space heaters beneath the tables. Please come out to join us.”

Turning to Taft, she adds, “That said, let me thank Dr. Taft for such a memorable lecture. You certainly made quite an impression.” She smiles, but with a certain restraint.

The audience applauds again, then slowly begins to filter through the exit.

Taft watches it do so, and I in turn watch him. This is one of the few times I have ever seen the man, recluse that he is. Now I finally understand why Paul finds him so magnetic. Even when you know he’s making a game of you, it’s almost impossible to take your eyes off him.

Slowly Taft begins to hulk across the stage. As the white screen mechanically retracts into a slot in the ceiling, the three slides become a whisper of gray over the blackboards beyond. I can barely make out the wild animals devouring the women’s remains, the child floating off into the air.

“You coming?” Charlie asks, lingering behind Gil by the exit.

I hurry after them.

Chapter 11

“You couldn’t find Paul?” Charlie asks once I’ve caught up.

“He didn’t want my help.”

But when I mention what I overheard outside, Charlie looks at me as if I shouldn’t have let him go. Someone stops beside us to greet Gil, and Charlie turns to me.

“Did Paul go after Curry?” he asks.

I shake my head. “Bill Stein.”

“Are you guys coming to the reception?” Gil calls out, sensing a quick getaway. “We could use the turnout.”

“Sure,” I say, and Gil seems pacified. His mind is elsewhere; we’re returning to his element.

“We’ll have to avoid Jack Parlow and Kelly—they only want to talk about the ball,” he says, returning to our sides. “But it shouldn’t be bad.”