The Sable Quean (9 page)

Authors: Brian Jacques

“Brother Tollum, start with yonder sycamore, then take that beech next to it. Oh, an’ there’s an oak further along. Tell yore crew t’chop ’em well back, all those long branches.”

The gaunt Bellringer nodded solemnly. “Right y’are, Skip. We’ll get right to it!”

The Otter Chieftain made for the east wallsteps, where he met a group of Dibbuns about to go up.

“Ahoy, mateys! Where do ye think yore off to?”

Guffy the molebabe was waving a table fork, which he deemed a very useful implement. “Ho, doan’t ee fret about us’n’s, zurr. We’m a-goin’ up thurr to ’elp out, hurr aye!”

The big otter smiled. “Well, thankee, mates, but you ain’t allowed on the walltops until you’ve growed a bit. I’m afraid ’tis a bit dangerous for Dibbuns. Run off an’ play, now, there’s good liddle beasts.”

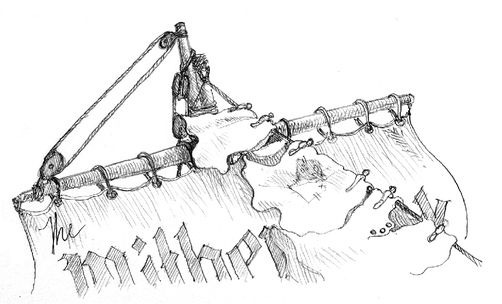

Foremole Darbee and his crew were on the ramparts. Though not greatly fond of heights, the moles worked industriously. Tollum’s squirrels would tie ropes to the chosen branches, throwing them across to the moles. Tugging hard on the ropes, the molecrew stopped the branches springing and bouncing. It was a lot easier to cut the wood once it was held steady. Whenever one was sawn or chopped through, Skipper would yell, “Ahoy, mates, heave ’er away!”

Some hefty limbs were hauled onto the walltops. They were dropped down to the Abbey lawns, where other Redwallers would cut them into small lengths, either for Friar Soogum’s firewood store or for Cellarmole Gurjee’s workshop. Good timber was never wasted.

The Ravager group were crouching in the ditch by the west wall, when Daclaw held up a paw for silence. He listened intently.

“Where’s all that noise comin’ from?”

“Shall I go an’ see, Chief?” Dinko volunteered.

Daclaw ignored him, pointing to a fat weasel. “Slopgut, you go. See wot it is an’ report straight back.”

Dinko did not like being left out. He was curious. “Wot d’ye think it is, Chief?”

Daclaw stamped on the young rat’s tail. “We’ll get t’know when Slopgut gits back. Why d’ye think I sent ’im, thick’ead? Now, shut yer trap!”

The work was going well on the east side. Stout branches of sycamore, beech, oak and hornbeam were being sawn into manageable sections by Sister Fumbril and a big hedgehog named Bartij, who besides being the Infirmary Sister’s aide, was also Redwall’s orchard gardener. Together they worked a double-pawed logsaw, keeping up a steady rhythm.

Brother Tollum called out to Skipper, “There goes the last branch, Skip, a nice piece o’ spruce!”

Darbee Foremole waved to his crew. “Haul ’er in, moi beauties. Ee job bee’s well dunn!”

Granvy clapped his paws cheerfully. “Aye, an’ just in time, here comes lunch!”

Hogwife Drull and her kitchen helpers hove into view. They were wheeling two trolleys piled high with good things to eat. Abbess Marjoram was with them. Molebabe Guffy and his friend, a squirrel Dibbun called Tassy, took the Abbess by her paws.

“Yurr, marm, cumm an’ see all ee wudd we’m chop pered up furr ee—b’ain’t that roight, Tassy?”

Marjoram chuckled. “Is that little Miss Tassy under all that sawdust and woodchips?”

The tiny squirrelmaid piped up, “I been very, very bizzy wivva natchet, chop chop!”

The Abbess dusted bark chips from Tassy’s ears. “Then you should be ready for some mushroom and leek soup and vegetable pasties. Then we’ve got apple and black currant crumble with arrowroot sauce.”

Everybeast surged forward at the mention of the treats to come. They were halted by Skipper’s shout.

“Sit down where y’are, all of ye, or there’ll be no lunch!”

He bowed gallantly to Drull and the Abbess. “Serve away, marms. Feed these savage beasts, if ye please!”

Guffy scowled darkly as he plumped down on the lawn. “Samwidge beast you’m self, zurr!”

Slopgut had watched the tree-lopping exercise. He scurried back and reported to Daclaw.

Furtively the group leader took his Ravagers around to the east wall—the wickergate was open. Bidding the rest to wait in the shrubbery, Daclaw and his mate, Raddi, peeped carefully through the gateway. Raddi watched the Redwallers lunching. She could smell the soup and the other food. The ferret licked her lips.

“I don’t blame young Globby wantin’ vittles like that. Makes ye wish y’was a woodlander yerself, don’t it?”

Daclaw glared at her. “Don’t talk like that, mate. If’n Zwilt the Shade hears ye, it’s sure death!”

Raddi pulled him back from the gateway suddenly.

“Wot did ye do that for?” Daclaw protested indignantly.

She clamped a paw around his mouth, whispering fiercely, “Didn’t ye see? There’s two young uns comin’ this way. The others haven’t noticed ’em. I think they’re takin’ their vittles out into the woods, mebbe to ’ave a picnic. Lissen, mate, we’ll grab the pair of ’em, gag their mouths an’ clear out of ’ere fast before they’re missed. Are ye ready?”

Daclaw whipped off his tattered shirt, tearing it into two makeshift gags. He passed one to Raddi.

“Ready as I’ll ever be, mate. Ssshh, I can ’ear ’em!”

Back inside on the Abbey lawn, everybeast relaxed after the work, lying about in the sun as they enjoyed a well-earned lunch.

Sister Fumbril made certain the Abbess was sure to hear her as she called out her request. “Perhaps some kind an’ beautiful creature’ll give us permission to carry on with the Redwall Bard Contest. Round about teatime this afternoon, in front of the gatehouse—that’s a quiet, sunny place.”

Granvy wiped soup from his whiskers, commenting, “Sunny it may be, but quiet? Not with this lot scrapin’ fiddles, bangin’ drums an’ caterwaulin’ away. What d’ye think, Mother Abbess?”

Marjoram chuckled. “Then you’d best plug your ears up, my friend, because the kind, beautiful creature has just given her permission for the contest to carry on.”

Brother Tollum waited until the cheering had died down before he asserted his claim. “Er, I think it was my turn to sing next, right, Granvy?” The hedgehog Recorder sighed. “So be it, Brother. But please don’t sing any mournful dirges with a hundred verses.”

Skipper smiled mischievously. “Oh, I dunno. I think ole Tollum’s songs are nice an’ restful. How’s about ‘The Burial Lament for the Flattened Frog’s Granpa’?”

Tollum brightened up slightly. “I know that one!”

There were yells of dismay and groans of mock despair. The Redwallers shouted impassioned protests, plus some rather impudent insults. They carried on eating lunch and joking about various singers.

Nobeast had noticed the absence of two little Dibbuns, who had been trapped, gagged and carried off by a band of vermin Ravagers.

7

It was a pleasant enough stream, running from the woodlands out onto the flatlands. However, this was where Oakheart Witherspyk ran the raft aground. The big, florid hedgehog had dozed off at the tiller, causing his craft to bump over some rocks which lurked in the shallows. The

Streamlass

was a fine old craft, with a blockhouse of logs at its centre. It had ornate wooden rails and a single mast, from which hung strings of washing and a square canvas sail. The faded sign painted on this sail announced “The Witherspyk Performing Players.” (Though the sign painter had made a spelling error—the word

Performing

read “Preforming.”)

Streamlass

was a fine old craft, with a blockhouse of logs at its centre. It had ornate wooden rails and a single mast, from which hung strings of washing and a square canvas sail. The faded sign painted on this sail announced “The Witherspyk Performing Players.” (Though the sign painter had made a spelling error—the word

Performing

read “Preforming.”)

The shock of the raft bumping roughly aground caused chaos on board. Oakheart’s mother, Crumfiss, and his wife, Dymphnia, clutching baby Dubdub to her, came stampeding onto the streambank. These were followed by the rest of his family, four other hedgehogs, a mole, a squirrel, and two bankvoles. (The latter four creatures he and his wife had adopted.) Everybeast was waving paws in alarm and crying out, either in panic or anger.

Dymphnia bellowed at her husband, “Oakie, you dozed off again, you great bumbler!”

Rising from his armchair, which was nailed to the deck alongside the tiller, Oakheart pointed at himself, booming out dramatically, “Dozed? Did I hear you say dozed, marm? Nay, alas, ’twas a cunning twist of devious water current which cast us ashore thus. I never doze whilst navigating, never!”

A young hogmaid held a drooping paw to her brow, declaiming, “Oh, Papa, I thought we were all to be drowned, lost sadly ’neath the raging waters!”

Dymphnia wiped the babe’s snout on her shawl, casting a jaundiced eye on her daughter. “Do be quiet, Trajidia. Don’t interrupt your father. Well, Oakie, are we stuck here?”

Removing a flop-brimmed hat and sweeping aside his timeworn cloak, Oakheart stared glumly over the rail at a number of rocks beneath the surface.

“Aye, m’dear. Fickle fortune has swept us hard upon the strand. Rikkle, can you see if anything can be done to relieve our position? There’s a good chap!”

One of the bankvoles hurled himself into the water and vanished beneath the raft. After a brief moment, Trajidia, who never missed the opportunity to be dramatic, clasped her paws, staring wide-eyed at the place where Rikkle had submerged.

“Oh, oh, ’tis so hard to bear, one of such tender seasons, gone to a watery grave!”

One of her brothers, Rambuculus, smiled wickedly. “It’s plum duff for supper. If he doesn’t come up, can I have his share, Ma?”

Dymphnia clouted him over the ear with her free paw. “Ye hard-hearted young blight!”

Baby Dubdub, who was learning to speak by repeating the last words of his elders, shook a tiny paw at his brother. “Young blight!”

Rikkle climbed back aboard shaking himself, treating those nearby to a free shower. “Ain’t no good, Pa. We’re jammed tight, unless we can find somethin’ to lever ’er off with.”

Oakheart was not in the levering mood; he sniffed. “Leave it ’til the morrow. Perchance the stream may run at flood and float our

Streamlass

off.”

Streamlass

off.”

Wading into the shallows, he held forth a paw to assist his wife and their babe onto dry land.

“Right, Company, all paws ashore, if ye please!”

Dubdub shouted in his mother’s ear, “Paws ashore, please!”

They were grounded in the area where the trees thinned out onto the heathland. Oakheart rummaged through a pile of effects on the bank, coming up with a funnel fashioned from bark. This he held to his mouth and began calling aloud for the benefit of anybeast within hearing distance.

“Hear ye, hear ye, one and all!

All goodbeasts now, hark to me,

see here upon this very spot,

the Performing Witherspyk Company!

What’ll you see here when we start?

Why, tales to delight the rustic heart,

plays enacted on nature’s stage,

dramas of avarice, war and rage.

Stories of love to make you sigh,

tragedies bringing a tear to the eye.

Mayhaps a comedy we’ll make,

You’ll feel your ribs with laughter ache.

Yet what seek we as our reward?

Merely to share your supper board.

A drop to drink, a crust, perchance.

We act, we sing, recite or dance.

Aye, food would aid our noble cause,

though mainly we feed upon applause.

You’ll not regret a visit to see,

The Performing Witherspyk Companeeeeeeeee!”

All goodbeasts now, hark to me,

see here upon this very spot,

the Performing Witherspyk Company!

What’ll you see here when we start?

Why, tales to delight the rustic heart,

plays enacted on nature’s stage,

dramas of avarice, war and rage.

Stories of love to make you sigh,

tragedies bringing a tear to the eye.

Mayhaps a comedy we’ll make,

You’ll feel your ribs with laughter ache.

Yet what seek we as our reward?

Merely to share your supper board.

A drop to drink, a crust, perchance.

We act, we sing, recite or dance.

Aye, food would aid our noble cause,

though mainly we feed upon applause.

You’ll not regret a visit to see,

The Performing Witherspyk Companeeeeeeeee!”

Oakheart’s mother, Crumfiss, a venerable greyspiked hog, prodded him none too gently with her walking stick. “Oh, give your face a rest, Oakie. This is the back of nowhere. There’s nobeast around for leagues!”

Rambuculus sniggered wickedly. “Poke him again, Granma. Go on—good’n’hard!”

Crumfiss brandished the stick at him. “I’ll poke you, ye impudent young snickchops! Do somethin’ useful. Go on, gather firewood for your ma!”

Oakheart rounded on them, paw upraised. “Hist, voices, d’ye hear?”

From not too far off, a voice sounded, getting louder. “I say, there. Are you chaps callin’ to us, wot? Hold on a tick, we’ll be right with you!”

Two hares and a shrewmaid approached through the woodland fringe. It was Buckler, Diggs and Flib. Oakheart beamed a welcoming smile.

“Over here, friends. Over here!”

Flib wiggled a paw in one ear, wincing. “Do ye have ter yell through that thing?”

The florid hog lowered his megaphone. “Ah, forgive me, my dainty miss—force of habit, y’know.”

Flib scowled at him. “Ye can cut that out right now. I ain’t nobeast’s dainty miss—I’m Flib the Guosim, see!”

Buckler rapped her paw lightly with the bellrope. “Mind your manners. He’s just trying t’be friendly.”

Oakheart did not seem to take offence. He continued holding forth merrily. “Ah, a Guosim shrew, no less. Stout creatures. Perhaps you know one who is an acquaintance of mine, Jango Bigboat by name, something of a chieftain amongst his kind, I believe.”

Flib seemed flustered by the mention of Jango Bigboat. She dropped back, standing behind Diggs, murmuring, “No, I ain’t ’eard o’ that un, sir.”

After introductions had been made all round, Buckler strode down to the streambank, where he viewed the grounded raft.

“Mister Oakheart, perhaps we could help you to refloat your craft. It’s a wonderful thing—I’ve never seen one like it.”

Other books

Bing Crosby by Gary Giddins

Let's Get It On by Cheris Hodges

The Master's Mistress by Carole Mortimer

The Inscrutable Charlie Muffin by Brian Freemantle

Black Ops Chronicles: Dead Run by O'Neal, Pepper

Unspoken: Shadow Falls: After Dark by C. C. Hunter

The Da Vinci Deception by Thomas Swan

Hurricane Force (A Miss Fortune Mystery Book 7) by Jana DeLeon

Steel Breeze by Douglas Wynne