The Sagas of the Icelanders (37 page)

Read The Sagas of the Icelanders Online

Authors: Jane Smilely

Vatnsdala saga

Time of action

: 875–1000

Time of writing

: 1270–1320

The Saga of the People of Vatnsdal

begins in Norway, as do most sagas of Icelanders, though its strange and sombre opening has more in common with scenes from legendary sagas. The birth of Ingimund, patriarch of the people of Vatnsdal, serves as an affirmation of the power of reconciliation within a community, for the wife of his father Thorstein was the sister of a man whom he had killed. Ingimund fights on the king’s side in the battle of Havsfjord and, like other settlers such as Ketil Flat-nose, consents only reluctantly to abandon his estate and social position as he looks towards a new life in Iceland. A hidden talisman, the gift of King Harald Fair-hair, guides him to his new home in Vatnsdal, and the sense of a protective good fortune continues to accompany his lineage as they live their lives in the beautiful Vatnsdal countryside.

The events of the saga span five generations, but the narrative focus falls especially on the third of these, the sons of Ingimund and the conflicts in which they engage as they play their part in the creation myth of a region and a dynasty. On the death of Ingimund, his five sons divide among themselves the various tokens of family nobility: the farm, the ship and the wealth resulting from its trading voyages, the godord in which the family’s social authority is vested and the sword which symbolizes how all these elements can be defended. This weapon is shared by two of the sons, who take turns at wearing it at public gatherings. The saga explores the way in which successive generations handle these emblems of their family’s claim to distinction, as they strive to maintain order among volatile kinsfolk, and within the broader and often turbulent community.

In its presentation of character the saga is generally clear and succinct.

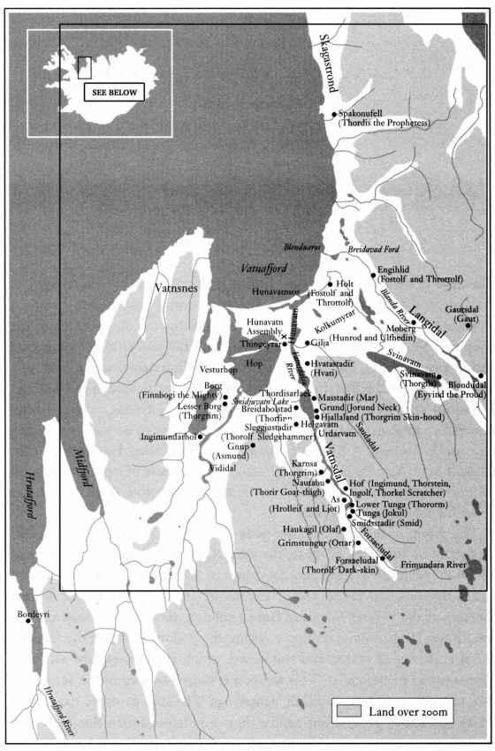

Vatnsdal

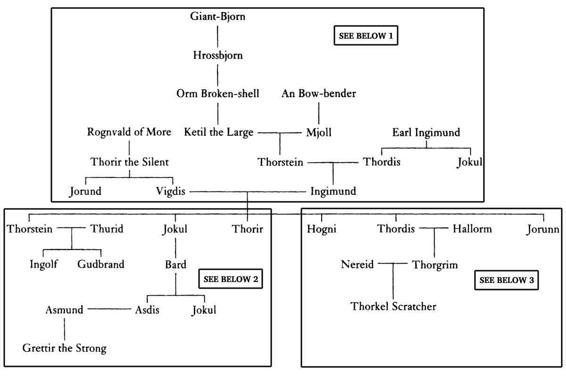

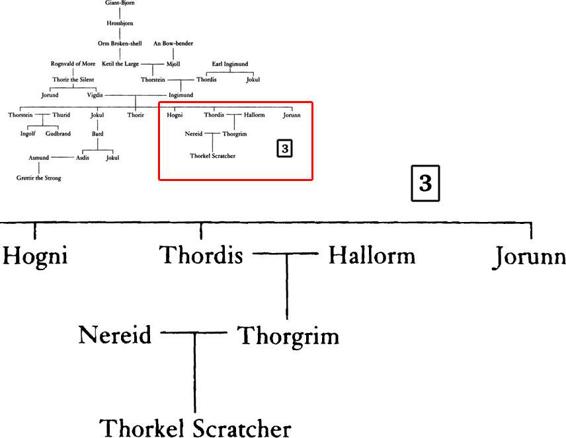

Ingimund’s Ancestors and Family in Vatnsdal

Its author’s sympathies, while never stated directly, are there for all to see: he even seems to relish the grotesque and sometimes comic aspect of the rogues and wretches whom his heroes encounter. The cast of characters is richly variegated, and the saga moves swiftly from one colourful episode to another, with its Viking expeditions, sea battles, pagan temples, berserk fits, witches and sorcerers, monstrous cats, murderous attacks and beautiful women. At times the narrative rises to classic splendour, as in the magnificent scene of Ingimund’s death (chs. 22–3). The ethic of the saga is undogmatically Christian, as the servants of good overcome the manifestations of a darker world, and heathen notions of fate and self-reliance merge seamlessly with a divine providence which watches over all of noble spirit.

Some scholars have been tempted to think that

The Saga of the People of Vatnsdal

, with its learned style and its sense that nobility and goodness will always defeat malevolent forces in this world and the next, may have links with the Benedictine monastery and literary centre at Thingeyrar in the district in which the main action of the saga takes place.

The Saga of the People of Vatnsdal

is thought to have been written around the year 1300, but is only preserved in later manuscripts; the oldest vellum fragment (AM 445 b 4to) is dated 1390–1425. It is translated here by Andrew Wawn from the text in

Íslenzk fornrit

, vol. 8 (Reykjavik, 1939).

1

There was a man named Ketil, nicknamed the Large. He was a mighty man, and lived on a farm called Romsdal, in the north of Norway. He was the son of Orm Broken-shell, who was the son of Hrossbjorn, son of Giant-Bjorn from the north of Norway. There were district-kings in Norway when the events of this saga took place. Ketil was a noble and wealthy man, of great strength, and very brave in all his exploits. He had been away raiding during the early part of his life, but as the years caught up with him he settled down on his estates. He married Mjoll, the daughter of An Bow-bender. By her Ketil had a son called Thorstein. He was good-looking though nothing out of the ordinary in terms of size or strength – his bearing and talents were up to the high standard of other young men at that time. Thorstein was eighteen years old when these events took place.

At this time people had come to believe that there must be robbers or felons on the road which lay between Jamtland and Romsdal, because no one who set out along that highway ever came back; and even with fifteen or twenty people travelling together, not one had returned home. Thus people concluded that some extraordinary being must be living out there. Ketil’s men suffered least from this harassment, both in terms of loss of life and damage to property, and there was a good deal of reproachful talk to the effect that the man who was chieftain of the region was proving no sort of leader, in that no measures had been taken against such outrages. People claimed that Ketil had aged greatly; he showed little reaction, but pondered what had been said.

2

On one occasion

*

Ketil said to Thorstein his son, ‘The behaviour of young men today is not what it was when I was young. In those days men hankered after deeds of derring-do, either by going raiding or by winning wealth and honour through exploits in which there was some element of danger. But nowadays young men want to be stay-at-homes, and sit by the fire, and stuff their stomachs with mead and ale; and so it is that manliness and bravery are on the wane. I have won wealth and honour because I dared to face danger and tough single combats. You, Thorstein, have been blessed with little in the way of strength and size. It is more than likely that your deeds will follow suit, and that your courage and daring will match your size, because you have no desire to emulate the exploits of your ancestors; you reveal yourself to be just as you look, with your spirit matching your size. It was once the custom of powerful men, kings or earls – those who were our peers – that they went off raiding, and won riches and renown for themselves, and such wealth did not count as part of any legacy, nor did a son inherit it from his father; rather was the money to lie in the tomb alongside the chieftain himself. And even if the sons inherited the lands, they were unable to sustain their high status, if honour counted for anything, unless they put themselves and their men at risk and went into battle, thereby winning for themselves, each in his turn, wealth and renown – and so following in the footsteps of their kinsmen. I believe that the old warriors’ ways are unknown to you – I wish I could teach them to you. You have now reached the age when it would be right for you to put yourself to the test, and find out what fate has in store for you.’

Thorstein answered, ‘If ever provocation worked, this would be provocation enough.’

He stood up and walked away and was very angry.

A great forest lay between Romsdal and Oppland, through which a highway ran, though it was then impassable because of the felons who were thought to be lying in wait, though no one could say anything for sure about this. At that time it seemed quite an achievement to come up with any solution to the problem.

3

It was shortly after father and son had talked together that Thorstein left the drinking on his own. His uppermost thought was to put his father’s luck to the test, and no longer to endure his taunting but to place himself at some risk. He took his horse and rode off on his own to the forest, to the place which he thought offered the greatest likelihood of encountering the felons, even though there seemed little hope of success against the kind of mighty force which he thought would be there. By this time, however, he would rather have laid down his life than have a wasted journey.

He tethered his horse at the edge of the forest, and proceeded on foot

and found a path which led off the main track; and after he had walked for quite some time, he came across a large and well-built house in the forest. Thorstein felt sure that the owner of the building was whoever had made the highway impassable for people. Thorstein then went into the hall, and there came across huge chests and many a treasure. There was a great pile of firewood and opposite this were sacks of wares and goods of every kind. Thorstein saw a bed there, far larger than any he had ever seen before. It seemed to him that the person who fitted into such a bed must be quite a size. The bed had splendid curtaining. There was also a table laid with clean linen, rich delicacies and the finest drink; Thorstein did not touch these things. He then sought some means whereby he would not immediately catch the eye of whoever lived in the house because, before they saw or spoke to each other, Thorstein wanted to find out what he was up against. He then made his way between the sacks and into the pile of goods and sat down there.

Later, well into the evening, he heard a great din outside, and a man then came in, leading a horse behind him. He was of massive size, with shoulder-length locks of fair hair. Thorstein thought him a very handsome fellow. Then the man stirred up the fire, having first led his horse to its stall. He put out a washing basin, washed his hands and dried them on a white cloth. From a cask he poured fine drink into a large goblet, and then he began to eat. Everything about this man’s behaviour seemed to Thorstein very refined and remarkable. He was much larger than Ketil, his father, and seemed, as indeed he was, a mountain of a man.

When the hall-dweller had finished eating, he sat by the fire, gazed into it and said: ‘There’s been some disturbance here; the fire has burned down more than I expected; I think that it has been stirred recently. I don’t know what this means; it may be that men have come here, and have designs on my life – and not without reason. I will go and search the house.’

He then took up a smouldering brand, and went off searching, and came to where the pile of goods stood. It was so arranged that someone could get from this pile to the big chimney which opened into the hall. By the time the robber searched the pile, Thorstein was outside, and the hall-dweller could not find him, because it was not Thorstein’s destiny to be killed there. The hall-dweller searched the house three times and found nothing.

Then he said, ‘I will leave things as they are for now; the shape of events is not clear, and it may work out in my affairs, as the saying goes, that “bad counsel turns out badly”. ’

He then went to his bed and took off his short-sword. Thorstein regarded

this sword as a great treasure and very likely to cut well, and he felt that the weapon would serve his purpose if he could get hold of it. He recalled his father’s incitement – that strength and daring would be needed to accomplish this or any other bold deeds, but that glory and glittering coins would be the reward, and he would then be deemed to have done better than by sitting at his mother’s hearth. He then also recalled that his father had said that he was no better at wielding a weapon than a daughter or any other woman, and that it would better serve his kinsmen’s honour if there were a gap in the family line rather than having him. This drove Thorstein on, and he looked for an opportunity to avenge single-handedly the wrongs done to many people; yet, on the other hand, it seemed to him that the man would be a great loss.

In time the hall-dweller fell asleep and Thorstein tested how soundly he slept by making a noise. At this the man woke up and turned on to his side. More time passed and Thorstein tried again and once more the man stirred, though less than before. On the third occasion Thorstein approached and struck a mighty blow on the bed-post – and found that all was quiet with the man. Then Thorstein stirred up some flames in the fire and approached the bed; he wanted to see if the man was still there. Thorstein saw him lying there – he was sleeping face upwards in a gold-embroidered silk shirt. Thorstein then drew the short-sword and thrust at the mighty man’s chest and dealt him a deep wound. The man turned sharply and grabbed hold of Thorstein and pulled him up on to the bed alongside himself, and the sword remained in the wound – so strongly had Thorstein struck him that the sword-tip was stuck in the bed. This man was amazingly strong, however, and let the sword stay where it was; and Thorstein lay between him and the bed panel.

The wounded man said, ‘Who is this man who has dealt me such a blow?’

He answered, ‘My name is Thorstein, and I am the son of Ketil the Large.’

The man said, ‘I thought that I knew your name before, but I feel that I have in no way deserved this from you and your father, for I have done you both little or no harm. You have been rather too hasty and I rather too slow because I was ready to go away and abandon my wicked ways; but now I have complete power over you as to whether I let you live or die. If I treat you as you deserve and have laid yourself open to, then no one would be able to say a word about our dealings. But I think that the wisest course would be to spare your life, and it may be that I may derive some benefit from you if things work out well. I want now to tell you my name. I am Jokul, son of Ingimund, earl of Gotland; and in the manner of sons of mighty

men, I won riches for myself, though in a rather violent way, but now I was ready to leave. If this gift of your life seems worth anything to you, then go and meet my father, but speak first with my mother who is named Vigdis and tell her on her own of our dealings and give her my loving greetings and ask her to seek reconciliation and friendship on your behalf with the earl so that he will let you marry Thordis, his daughter and my sister. Here now is gold which you must take as a token that it is I who send you. And though the news about me will seem a great grief to her, I believe that she will pay more heed to my love and message than to your deserts; something tells me that you will be a man of good fortune. And if you or your boys are blessed with sons, do not allow my name to die out – it is from this that I hope to derive some benefit, and I want this in return for sparing your life.’

Thorstein told him to do what he liked about sparing his life and any other matters, and said that he would not plead for anything. Jokul said that his life was now in his hands – ‘but you must have been sorely provoked into this by your father, and his plan has touched me to the quick, and I see that you would be quite content even if both of us were to die, but a greater future is in store for you. With you at their head no one will be without leadership, because of your daring and manliness, and my sister will be better looked after if you take her as your wife than if Vikings seize her as some spoil of war. Moreover, even if you are invited to rule in Gotland, return instead to your estate in Romsdal, because my father’s kinsmen will not grant you authority after his death, and it may be that terrible killings would lie in store for your kith and kin, and men would lose their innocent kinsmen. Do not mention my name in public except to your father and my kinsmen, because my life has been an ugly one and now has the reward it deserves, and that’s the way it goes with most wrongdoers. Take the gold here and keep it as a token, and draw out the short-sword – after this our conversation will not be a long one.’

Thorstein then drew out the short-sword and Jokul died.