The Sagas of the Icelanders (9 page)

Read The Sagas of the Icelanders Online

Authors: Jane Smilely

Listed below are some of the more recent books in English about the

Íslendinga sögur

and their historical and cultural backgrounds. Much authoritative work on the sagas exists only in the Icelandic language or in journal articles and is not included. References to this more specialized literature may be found by consulting Pulsiano and Wolf,

Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia

and Clover and Lindow,

Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Critical Guide

(see below).

Andersson, Theodore M.

The Problem of Icelandic Saga Origins: A Historical Survey

. New Haven, Conn. 1964.

—.

The Icelandic Family Saga: An Analytic Reading

. Cambridge, Mass. 1967.

Andersson, Theodore M. and Miller, William Ian.

Law and Literature in Medieval Iceland: Ljósvetntnga saga and Valla-Ljótssaga

. Stanford 1989.

The Book of Settlements (Landndmabok)

. Trans. Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards. Winnipeg 1972.

Bragger, A. W. and Shetelig, H.

The Viking Ships

. Oslo 1951.

Byock, Jesse L.

Feud in the Icelandic Saga

. Berkeley 1982.

—.

Medieval Iceland; Society, Sagas, and Power

. Berkeley 1988.

Clover, Carol J.

The Medieval Saga

. Ithaca, NY 1982.

— and Lindow, John (ed.).

Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Critical Guide. Islandica

XLV. Ithaca, NY 1985.

CluniesRoss, Margaret.

Prolonged Echoes: Old Norse Myths in Medieval Northern Society

. Vol. I:

The Myths

. Vol. II:

The Reception of Norse Myths in Medieval Iceland

. Odense, Denmark 1994, 1998.

Ellis Davidson, H. R.

Gods and Myths of Northern Europe

. Harmondsworth 1964.

Foote, Peter and Wilson, D. M.

The Viking Achievement

. Revised edn. London 1980.

Frank, Roberta.

The Old Norse Court Poetry Dróttkvatt Stanza. Islandica

XLII. Ithaca, NY 1978.

Gade, Kari Ellen.

The Structure of Old Norse Dróttkvatt Poetry. Islandica

IL. Ithaca, NY 1995.

Graham Campbell, James.

The Viking World

. London 1980.

Hallberg, Peter.

The Icelandic Saga

. Trans. Paul Schach. Lincoln, Neb. 1962.

Hastrup, Kirsten.

Culture and History in Medieval Iceland

. Oxford 1985.

Ingstad, Helge.

Westward to Vinland: The Discovery of Pre-Columbian Norse House-sites in North America

. Trans. Erik J. Friis. New York 1969.

Íslendingabók (The Book of the Icelanders)

. Trans. Halldór Hermannson. Ithaca, NY 1930.

Jesch, Judith.

Women in the Viking Age

, Rochester, NY 1991; Woodbridge, England 1992.

Jochens, Jenny.

Women in Old Norse Society

. Ithaca, NY 1995.

—.

Old Norse Images of Women

. Philadelphia 1996.

Jones, Gwyn.

A History of the Vikings

. 2nd edn. Oxford 1984.

Ker, W. P.

Epic and Romance: Essays on Medieval Literature

. 2nd edn. London 1908; rpt. New York 1957

Kristjánsson, Jónas.

Eddas and Sagas: Iceland’s Medieval Literature

. Trans. Peter Foote. Reykjavik 1992.

Kunz, Keneva.

Retellers of Tales: An Evaluation of English Translations of Laxdala Saga

. Reykjavik 1994.

The Laws of Early Iceland: Grágás, The Codex Regius of Grdgds with Material from Other Manuscripts

, I. Trans. Andrew Dennis, Peter Foote and Richard Perkins. Winnipeg 1980.

Lönnroth, Lars.

Njdls Saga: A Critical Introduction

. Berkeley 1976.

Madelung, Margaret A.

The Laxdala Saga: Its Structural Patterns

. Chapel Hill, NC 1972.

Meulengracht Sorensen, Preben.

Saga and Society: An Introduction to Old Norse Literature

. Trans. John Tucker. Odense, Denmark 1993.

—.

The Unmanly Man: Concepts of Sexual Defamation in Early Northern Society

. Trans. Joan Turville-Petre. Odense 1983.

Miller, William Ian.

Bloodtaking and Peacemaking: Feud, Law, and Society in Saga Iceland

. Chicago 1990.

Nordal, Sigurdur.

Icelandic Culture

. Trans. Vilhjálmur T. Bjarnar. Ithaca, NY 1990.

Ólason, Vésteinn.

Dialogues with the Viking Age: Narration and Representation in the Sagas of Icelanders

. Trans. Andrew Wawn. Reykjavik 1997.

Pálsson, Hermann.

Art and Ethics in Hrafrkel’s Saga

. Copenhagen 1971.

The Poetic Edda

. Trans. Carolyne Larrington. Oxford 1996.

Pulsiano, Phillip and Wolf, Kirsten,

et al

. (eds.).

Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia

. New York 1993.

Sawyer, Birgit and Peter.

Medieval Scandinavia: From Conversion to Reformation, circa 800–1500

. Minneapolis 1993.

Schach, Paul.

Icelandic Sagas

. Boston 1984.

Sigurdsson, Gísli.

The Gaelic Influence in Iceland: Historical and Literary Contacts

. Reykjavik 1988.

Steblin-Kamenskij, M. I.

The Saga Mind

. Trans. Kenneth H. Ober. Odense 1973.

Strayer, Joseph R. (editor-in-chief).

Dictionary of the Middle Ages

. New York 1982–8.

Sturluson, Snorri.

Edda

. Trans. Anthony Faulkes. London 1987.

—.

Heimskringla

. Trans. Samuel Laing, revised Jacqueline Simpson and Peter Foote. 3 vols. London 1961–4.

—.

Heimskringla

. Trans. Lee M. Hollander. Austin, Tex. 1964.

Sveinsson, Einar Olafur.

The Age of the Sturlungs: Icelandic Civilization in the Thirteenth Century

. Trans. Jóhann S. Hannesson.

Islandica

XXXVI. Ithaca, NY 1953.

—.

Njdls Saga: A Literary Masterpiece

. Ed. and trans. Paul Schach. Lincoln, Neb. 1971.

Tucker, John (ed.).

Sagas of the Icelanders

. New York 1989.

Turville-Petre, E. O. G.

Origins of Icelandic Literature

. Oxford 1953.

—.

Myth and Religion of the North

. London 1964.

—.

Scaldic Poetry

. Oxford 1976.

The sagas and tales in this book are reprinted from

The Complete Sagas of Icelanders I–V

, published 1997 by Leifur Eiríksson Publishing, Iceland, with minor alterations. This was the first complete edition of the forty sagas of Icelanders in English, and included forty-nine tales. All the material was translated specifically for the edition, with the exception of three sagas that were adapted to the general editorial policy. Robert Kellogg’s introduction has been expanded to reflect more closely the thematic framework of the present volume.

Örnólfur Thorsson chose the sagas and tales and supervised this volume, provided material for prefaces to individual sagas and compiled the explanatory material accompanying each. Gisli Sigurdsson wrote the preface to the Vinland Sagas and produced material for the Vinland maps. Bernard Scudder contributed to the prefaces and reworked all the explanatory material into the final English versions. Robert Kellogg and Robert Cook also read all the prefaces and made invaluable suggestions. Jean-Pierre Biard designed the maps. Örnólfur Thorsson and Viðar Hreinsson produced the Index of Characters.

The Reference section comes from Vol. V of

The Complete Sagas of Icelanders

, but in a slightly altered form here.

All the

Sagas of Icelanders

, also known as the

Family Sagas

, share certain characteristics of form and content, but they can be classified into several closer groupings. Three sets of criteria are generally used to classify them: time of writing and textual considerations; historical and geographical setting; and literary considerations (in particular theme and point of view). The present selection includes texts from most periods in the ‘Age of Writing’, but its chief aim is to show the diversity of good literature within the family saga canon, and it contains representatives of all main literary types, set in virtually all the known Viking world.

Many sagas in this selection begin with a prelude in Norway and trace the arrival of a particular family as settlers in a particular part of Iceland. Sometimes Norway supplies more than distant noble roots for the main characters – in

Gisli Sursson’s Saga

, for example, Gisli displays the blind obedience to the revenge ethic which will send him into exile in Iceland too, and in

Egil’s Saga

the first third of the action takes place in Norway, launching the running feud with the royal family there. The main focus of most sagas, however, is the third and fourth generation after the settlement. Although the

Sagas of Icelanders

as a whole span virtually all the Viking Age from the second half of the ninth century to the middle of the eleventh, most deal in the greatest detail with 975 to 1025. By this time the political and legal structure of the Commonwealth was firmly in place, so that the dominant theme of the conflict between individual and society has a clear frame of reference. Perhaps even more significantly, the fulcrum of these fifty years is the adoption of Christianity in 1000, when a new system of values and ethics replaced the ancient Viking code of personal honour, and also when the seeds of a new, centralized power structure were sown. The maturing society of farmers would become increasingly intolerant of the heroic individualism on whose vision and ideals it was originally founded. The friction between public law without executive power and men of action driven by personal motivation is crucial to the plots of most sagas.

A basic distinction can be established according to whether the point of view of the saga is the individual or society.

Biographical sagas

concentrate on an individual and his conflicts and relationships either with other individuals (seen in the

sagas of poets and warriors

such as Egil or Gunnlaug Serpent-tongue) or with society as a whole (in the

sagas of outlaws

such as Gisli Sursson). Since outlaws live on the fringes of society, we often see in them elements of a supernatural world which contrasts with the typical saga realism, although it is generally described with the same objective nonchalance. Significantly, we also see elements of fantasy on the fringes of the known geographical world in Greenland, both in the otherwise realistic

Vinland Sagas

and in the fantastical

Saga of

SAGAS FROM GREENLAND AND VINLAND

Eirik the Red’s Saga

The Saga of the Greenlanders

The Tale of the Greenlanders

POETS AND WARRIORS

Egil’s Saga

Kormak’s Saga

The Saga of Hallfred the

Troublesome Poet

The Saga of Bjorn, Champion

of the Hitardal People

The Saga of Gunnlaug

Serpent-tongue

The Saga of the Sworn Brothers

Killer-Glum’s Saga

Viglund’s Saga

OUTLAWS

Gisli Sursson’s Saga

The Saga of Grettir the Strong

The Saga of Hord and the People

of Holm

CHAMPIONS

Bard’s Saga

The Saga of Finnbogi the Mighty

The Saga of the People of

Kjalarnes

The Saga of Thord Menace

The Saga of the People of Floi

The Saga of Ref the Sly

Gold-Thorir’s Saga

The Saga of Gunnar, the Fool of

Keldugnup

REGIONAL FEUDS

SOUTH ICELAND

: Njal’s Saga

WEST ICELAND

: The Saga of

the People of Laxardal

The Saga of the Slayings on

the Heath

NORTH ICELAND: The Saga of

the People of Ljosavatn

Valla-Ljot’s Saga

The Saga of the People of

Svarfadardal

The Saga of the People of

Reykjadal and of Killer-Skuta

The Saga of the People of

Vatnsdal

EAST ICELAND: The Saga of

the People of Vopnafjord

The Saga of Droplaug’s Sons

The Saga of the People of

Fljotsdal

The Saga of Thorstein

the White

Thorstein Sidu-Hallsson’s Saga

WEALTH AND POWER

The Saga of the People of Eyri

Hen-Thorir’s Saga

The Saga of the Confederates

Olkofri’s Saga

The Saga of Hrafnkel Frey’s Godi

The Saga of Havard of Isafjord

Types of Sagas

Ref the Sly

. Ref is an example of a champion, a strong individual who defends the weak or undertakes ordeals. This branch of saga writing often has a picaresque or roguish element to it and is sometimes closer to folk legend than to history. Certain episodes in

Gisli Sursson’s Saga

and

Egil s Saga

are in this vein too; interestingly, even champions have to perform their noble deeds either outside Iceland or outside human society in outlawry.

Opposing the biographical sagas are the

sagas of feuds

, typically located in a relatively small district which in a sense assumes the central role in the action. An example is

The Saga of the People of Vatnsdal

, which is a family saga describing five generations of chieftains who live in a district with which they clearly have strong emotional bonds. The concept of the man of authority, the godi, is essential to this saga, but even more to two others spanning a much shorter time,

The Saga of Hrafnkel Frey’s Godi

and

The Saga of the Confederates

. These two sagas are succinct but thorough examinations of local power and authority: the emergence of a leader of men, his duties as well as his rights, his response to subversion of his authority. It could be said that the leader figure is the antithesis of the outlaw figure at odds with society, and of the inwardly motivated poet at odds with himself.

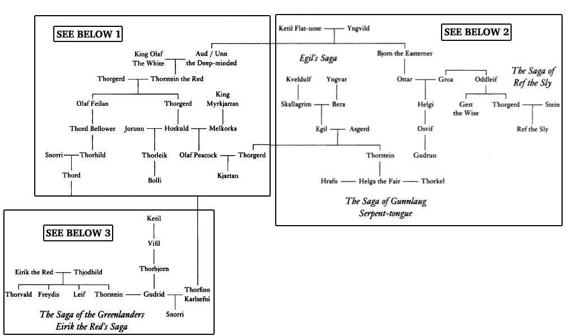

In the longer sagas of feud a vast gallery of characters is introduced, but inevitably a few strong personalities dominate the stage – for example Ingimund the Old and his son Jokul in Vatnsdal, and the triangle Bolli, Kjartan and Gudrun in Laxardal.

The Saga of the People of Laxardal

, like

Njal’s Saga

, is usually regarded as superior to the majority of the regional feud sagas, a masterpiece of epic narrative with tragic dimensions. The saga charts the dissent and dissolution within a single family as sharply etched characters struggle nobly through a series of fated events over which they have no control. Feuds escalate from trivial local squabbles into unstoppable vendettas. The male protagonists are splendid figures who die heroic deaths, while the women are strong characters who engineer much of the action.

Somewhere between the two main saga classifications are the two

Vinland Sagas

and one tale, which describe the western outposts of the Viking world: Eirik the Red’s discovery of Greenland and settlement there as leader of a large community, and the first European voyages to North America by his son Leif and later by Gudrid Thorbjarnardottir and Thorfinn Karlsefni.

From a historical perspective, the sagas in this selection map the Viking world and extend across the entire Viking Age: the movement from Norway, the flowering of national culture and localized settlements in Iceland, and the exploration and experience of new worlds. Characters and events recur