The Sahara (15 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

Downstream from Timbuktu and named after the majority Gao ethnic group that lived there, the empire was well placed to make good use of its position as a riverine transport hub, and to challenge the authority of the Mali Empire as that state’s power began to wane. It was under the nearly 39-year reign of Sunni Ali at the very end of the fifteenth century that the Songhai Empire really grew with one military victory after another, resulting in control of all trade up and down the River Niger. Shortly after this growth spurt, which transformed Songhai into a region wide power, another important source visited the area, stopping at Timbuktu - by now in the Songhai rather than Mali Empire - as he went.

The medieval traveller and author of the

Description of Africa

, Leo Africanus, visited Timbuktu around 1510 with his uncle, who was on a diplomatic mission. As Leo tells us in his introduction, he was born al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Fasi in Granada circa 1494, and moved with his family to Fez. In his mid-twenties, while returning from performing the

hajj

he was taken prisoner by Spanish corsairs. John Pory’s English translation from 1600 of the

Description

adds that Leo Africanus “Neither wanted he the best education that all Barbary could afford... So as I may justly say (if the comparison be tolerable) that as Moses was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians; so likewise was Leo, in that of the Arabians and Moors.” His captors, recognizing their prisoner’s superior intellect, made a gift of him to Pope Leo X, and Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Fasi was reinvented as Joannes Leo Africanus.

Once settled in Rome, Leo Africanus or Leo the African was commissioned to produce a description of Africa based on his extensive travels there. The ignorance regarding the interior parts of Africa at the time of writing is hard to imagine today. Maps before this time still featured fanciful descriptions of places and creatures. As the opening paragraph of Leo’s

Description

puts it, “That part of inhabited land extending southward, which we call Africa, and the Greeks Libya, is one of the three general parts of the world known to our ancestors; which in very deed was not thoroughly known by them discovered, both because the inlands could not be travelled in regard of huge deserts full of dangerous sands, which being driven by the wind, put travellers in extreme hazard of their lives.”

Leo Africanus’ description of Timbuktu is extensive, and includes numerous details such as the fact that the “houses here are built in the shape of bells, the walls are stakes or hurdles plastered over with clay and the houses covered with reeds.” In addition, while the majority of Europe continued to view Timbuktu as a city isolated from the world, this was not the case in Muslim Andalusia. As Leo explains, “Yet there is a most stately temple to be seen, the walls whereof are made of stone and lime; and a royal palace also built by a most excellent artist from Granada,” adding: ‘‘And hither do the Barbary merchants bring cloth of Europe.”

Of greatest interest to the gold-hungry royal courts of Europe was information about the city’s legendary wealth. Regardless of European agendas, Leo pointedly highlights the value placed on learning above gold, noting: “And hither are brought diverse manuscripts or written books out of Barbary, which are sold for more money than any other merchandise. The coin of Timbuktu is of gold without any stamp or superscription: but in matters of small value they use certain shells brought hither out of the kingdom of Persia.” This last point is another indication of how widespread the Songhai Empire’s trading networks were, with Persia and the Barbary Coast both being in regular contact with the kingdom in the desert.

If, however, any ruling power from Europe ever considered taking the kingdom by force, a note on the military might that travelled with the emperor would be worth remembering: “He hath always 3,000 horsemen, and a great number of footmen that shoot poisoned arrows, attending upon him. They have often skirmishes with those that refuse to pay tribute, and so many as they take, they sell unto the merchants of Timbuktu.”

Pory’s translation was a sensation upon its publication, and read avidly for information about the unknown continent. Considering the scarcity of information, the success it enjoyed should not come as a great surprise providing, as it did, much detail otherwise hidden from European scholars, including, for example, the name of the great desert: “But Libya propria, retaineth till this present the name of Libya, and is that part which the Arabians call Sarra, which worde signifieth a desert.” Ben Jonson admitted that he had consulted all available sources when, in 1605, he wrote his

Masque of Blackness

, including “Pliny, Solinus, Ptolemy, and ... Leo the African.”

The Songhai Empire was eventually destroyed in 1591, almost exactly one hundred years after the demise of the Muslim Kingdom of Granada that signalled the end of Muslim empires in Iberia. Songhai fell to a force of Moroccan musketeers, who marched across the Sahara on the orders of Ahmed al-Mansur al-Dhahabi, the Golden Conqueror and head of the Saadi dynasty. The army was commanded by the Spanish-born eunuch and forced childhood convert to Islam, Judar Pasha, who was famed for having a personal bodyguard of eighty Christians. The force consisted of 1500 light cavalry, 2500 arquebusiers (forerunners of modern riflemen) and infantry as well as eight English cannon. For logistical support the caravan had 8000 camels, 1000 packhorses and 1000 stable-hands.

The Moroccan force was confronted at Tondibi, north of Gao, by a much larger Songhai army of 40,000 men and cavalry, raised by the ruler of Songhai, Askia Ishaq II. One thousand cattle also accompanied his force, which were meant to screen the infantry as they advanced against the Moroccans. Unfortunately for the defenders, the Battle of Tondibi did not go in their favour. As soon as the arquebuses were fired, the unfamiliar noise, smoke and smell of the gunpowder-powered weapons scared the cattle, which turned and stampeded through the defenders’ lines. Judar quickly completed his campaign of conquest, sacking the major cities of Gao, Djenne and Timbuktu, and bringing the Songhai Empire to a crashing end.

The Moroccans were disappointed with what gold they found as booty was largely absent. Long gone, the gold trade that had spread far beyond the Sahara dwindled, and so too was ended the great university complex, leaving Timbuktu a shadow of itself, a dusty desert town and a legend. Despite this, news of this paucity of gold failed to reach Europe, and Timbuktu remained the goal of many Saharan explorers into the nineteenth century. Ironically, the prize of 10,000 francs offered by the French Societe Geographique for the first person to reach Timbuktu and return with information about the city was worth more than the gold available in the city by the time Rene Caillie claimed the prize in the 1820s.

The earliest eastern Sudanic Empire from this era to leave a distinct historical trail was Kanem. Occupying much of the Tenere Desert, Lake Chad’s northern shores and the Tibesti Mountains to the north, the Kanem Empire emerged around 700 CE and survived in one form or another through numerous successor states until 1893. The Empire of Bornu was a most important partner state that ensured this longevity, including a period when the two are known by the hyphenated title, Kanem-Bornu.

Ibn Khaldun noted the existence of the Kanem Empire, writing: “To the south of the country of Gawgaw lies the territory of Kanem, a Negro nation. Beyond them are the Wangarah on the border of the Sudanese Nile [actually the Niger] to the North.” Founded by the semi-nomadic Tebu-speaking Zaghawa tribe, by the time Yaqubi wrote about them in 890, the kingdom’s influence, but not control, stretched as far as the Nile Valley and Kingdom of Nubia. With the growth in influence of Kanem, direct Zaghawa power declined, and they retreated eastward to Darfur. While other Arab geographers contributed occasional details regarding Kanem, the greatest source of information about them is the

Gigram

or

Royal Chronicle

. This document, an official history of the kingdom, was only discovered by chance in 1851 by the explorer Heinrich Barth.

The merger of the Kingdoms of Kanem and Bornu was followed by a period of stability, reform and growth, which lasted until the middle of the seventeenth century. Within the borders of Kanem-Bornu was the important oasis town of Bilma, in the heart of the Tenere in today’s Niger. This small town remains a centre of salt and natron production, and lies on one of the few authentic trans-Saharan trade routes still in use. Some three hundred miles north of Lake Chad, Bilma is remoter even than Timbuktu, the archetype of a lonely place.

From the 1660s until the end of the nineteenth century Bornu was in decline. A number of typical explanations for this include divided leadership and sons who were not fit to take on their fathers’ mantles. Unlike its heyday at the turn of the seventeenth century, by the 1870s Bornu was a weak and divided empire, in which slaves were in the majority, controlled in turn by more slaves.

The end was swift, and the empire was overrun by Rabih as-Zubayr, a Sudanese warlord and one-time cavalryman for an irregular Egyptian force fighting in Ethiopia. Rabih’s conquest of Bornu allowed him to run a personal empire until his death in a showdown against French forces in April 1900. After his defeat, the French took all of his territories in the west, towards Niger, and the English claimed Bornu.

In the centuries before the fall of Bornu, Europe was still almost wholly ignorant of the Saharan interior, a source of embarrassment for those living in and after the Enlightenment. Something had to be done to banish such ignorance. In European government departments and centres of learning moves were afoot to do just that. Beginning with the creation of learned societies devoted to scientific discovery, and ending with imperial expansion, the relationship between the peoples of the Sahara and Europe was about to change forever.

European Forays - The African Association and Napoleon

“I had a passionate desire to examine into [sic] the productions of a country so little known, and to become experimentally acquainted with the modes of life and character of the natives.”

Mungo Park,

Travels in the Interior of Africa

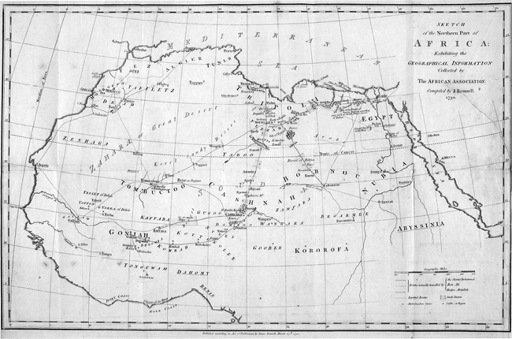

Eighteenth-century European knowledge of the majority of the African continent, including the deserts of North Africa, was limited. More was known about the Amazon and the Himalayas than the Sahara. Rumours of golden cities and tales of one-eyed giants did not constitute scientific knowledge. As a result, meeting on 9 June 1788 in the St. Alban’s Tavern, London, a group of gentlemen banded together in order to start the work of correcting what they saw as an egregious gap in human understanding. The minutes of that meeting stated, “Sensible of this stigma, and desirous of rescuing the age from a charge of ignorance, which, in other respects, belongs so little to its character, a few individuals, strongly impressed with a conviction of the practicability and utility of thus enlarging the fund of human knowledge, have formed the plan of an Association for promoting the discovery of the interior parts of Africa.”

The founders of the African Association were learned men, with knowledge of the Classics that made them aware of the ties ancient Greece and Rome enjoyed with North Africa. These great Ancient civilizations, the inspiration for much European thinking in the late eighteenth century, had founded cities across the breadth of North Africa as well as having contact with the tribes of the desert’s interior, establishing trade, with varying degrees of success, along well-established trans-Saharan routes. That Englishmen living through the Age of Enlightenment knew less about the Sahara than had their Classical antecedents was an affront to their dignity.

Serious exploration of the Sahara was impossible, though, while people relied on a twelfth-century copy of Ptolemy’s second-century map, and for local intelligence they turned to Herodotus and Pliny as much as to the most up-to-date volume dealing with Saharan geography: Leo Africanus’ 1550

Description of Africa

. These tomes were hardly sufficient preparation before setting off to “the Interior Parts of Africa’’. For example, both al-Idrisi and Leo Africanus insisted that the River Niger flowed east to west, emerging into the Atlantic in the area of Senegal and the Gambia, which was wrong. Pliny got it right when he said that the river flowed from west to east, but he then blundered when he said it ended where it entered the Nile. There were also those who believed Ptolemy’s view that the Niger was an independent, intra-African river that did not empty out into any sea or ocean at all.