The Sahara (39 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

The Bedu themselves, having settled in the region more than a millennium ago can comfortably claim indigenous status, so much so that they are often seen as the least distinct of the region’s racial groups. This is especially true for those who have abandoned the traditional, nomadic way of life.

The most numerous and widespread of all the indigenous people who live in the Sahara are the Berber, who can be found from the Isle of Djerba, in Tunisia to the north to as far south as the River Niger and whose settlements are spread from as far east as the oasis of Siwa to the Atlantic coast in the west. In spite of this extensive range, their heartland remains the north-west parts of the Sahara in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. Famous Berber names include such diverse characters as St. Augustine, Ibn Battuta and the French-born international footballer Zinedine Zidane.

Although known in the West as Berbers, it is very rare for the people to use this name, referring to themselves rather as Amazigh or Imazighen, which Leo Africanus claimed meant “free people” in their native language, Tamazight. The Tamazight language group demonstrates, as one would expect considering the distance over which it is spread, great variety from one side of the Sahara to the other. These dialects do, however, have a common Punic ancestry. Now extinct, Punic was derived from ancient Phoenician, which the Tamasheq script, Tifinagh, resembles.

Although it is not known where the Berbers came from, nor when they first entered the region, Ibn Khaldun says of them, “They belong to a powerful, formidable, brave, and numerous people; a true people like so many others the world has seen - like the Arabs, the Persians, the Greeks, and the Romans. The men who belong to this family of peoples have inhabited the Maghreb since the beginning.” The Romans also used specific names for specific Berber communities, for instance the Numidians and Mauri, from which latter term we derive Mauritania.

The Tuareg

The Tuareg are actually a branch of the Berber family, whose origins are likewise unknown. As Hanbury-Tenison observed in Worlds Within, “They are a Berber people, who consider themselves white, although their skin is burnt dark by the sky. Babies are born snow white.” He adds: “The Touareg, an ancient offshoot of the Kabyle Berbers of Algeria, were unappreciative of the ‘civilizing mission’ of the Roman legions and decided to put a thousand miles or more of desert between themselves and their would-be educators.” Many Tuareg still live according to their traditional nomadic pastoral lifestyle but they are increasingly found leading settled lives, albeit still largely confined to their traditional Saharan heartland in southern Algeria, northern Mali and Niger. Their familiarity with the desert means the Tuareg have an unparalleled understanding of what it means to be a Saharan, being unique in their ability to survive the unforgiving desert. This knowledge, or philosophy, is encapsulated in the Tuareg saying, “The desert rules you, you don’t rule the desert.”

As a culturally and historically nomadic people, the Tuareg suffered in the colonial and post-colonial divisions of the Sahara, with their traditional lands being divided among modern nation states, including Algeria, Libya, Mali, Mauritania and Niger. The Tuareg were known as great warriors before the arrival of Europeans bearing rifles, which immediately made swordsmanship redundant. Today Tuareg blacksmiths still produce traditional swords, but very much as decorative items. Tuareg silversmiths are renowned for their fine jewellery, which is now primarily made for tourists conducted across the desert to the craft vendors by Tuareg guides.

Like the main branch of the family, the name Tuareg is a foreign term of ancient standing, the Tuareg themselves using various other names including Imazaghan and Kel Tamasheq, or speakers of Tamasheq. According to Paul Bowles, Tuareg means “lost souls”, and has only been in use since the sixteenth century. Some writers have consequently wondered if perhaps these central Sahara people are not in fact the otherwise long-since vanished Garamantes.

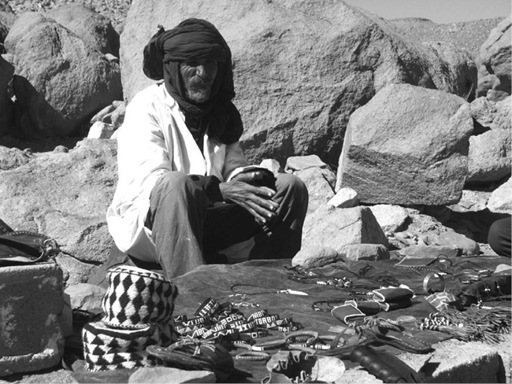

A Tuareg craftsman, Algeria

Whatever name is used by or for them, the Tuareg’s most famous moniker remains the Blue Men. The nickname comes from the brilliant blue turban or veil that the men wear, which they use to cover their heads and most of the face. Known locally as a

tagelmust

, the cloth traditionally gets its colour from being dyed with indigo, and can be up to forty feet in length. Over time the indigo will leech from the cloth, staining the wearers’ skin a distinctive shade of blue, making them literally the Blue Men of the Sahara. Interestingly, in Tuareg society it is only the men who cover their faces, women going about with head and face completely exposed. Tuareg women also have a saying: “A good husband is the one who brings enough water.” This is as practical a test of masculine mettle as any in their dry world.

Although not at present a significant economic sector, tourism once held out the promise of large income in the heart of traditional Tuareg lands. Today the industry is in tatters, with many would-be desert tourists put off by the threat of kidnapping and more general banditry by genuine or otherwise al-Qaeda-affiliated groups. By far the biggest Tuareg cultural event to draw foreign visitors is the music-oriented Desert Festival, which is held annually in Mali, terrorism permitting.

Tinariwen

Among Tuareg musicians, Tinariwen - from the plural of

tenere

, or desert, in Tamasheq - have undoubtedly met with the greatest international success. Apart from the appeal of a gutsy, bluesy, guitar-driven sound, the band became the darlings of western promoters and the media alike with their background as desert warriors, literally veterans of fighting in Libya and Mali. Having hung up their weapons, Tinariwen have since graced the stages of western music festivals from Glastonbury to Womad, and have had their music lauded by, among many others, U2, Radiohead, Carlos Santana and Henry Rollins.

Many early European travellers believed the Tuareg made their living solely by robbing desert travellers. As a result, the

tagelmust

was thought to be primarily a device for concealing the wearer’s identity, rather than an important means of keeping sand out of eyes, nose and mouth. By the late twentieth century they had largely managed to shake off this reputation for thievery, and now increasingly work as guides in the burgeoning market for Saharan tourism. Hanbury-Tenison, who spent forty days with a group of Tuareg, wrote of his experience:

One of the best things about this whole time has been how happy my team has been, consistently. There has not been a cross face or a bad mood from any of them. They start and end each day in the same way, chatting, smiling and laughing as they crouch around the fire. I know ‘‘Africans” are supposed to be happy people, but the Tuareg dismiss all black people from the south as “les Africains” and would be horrified to be lumped in with them. This is a Tuareg thing.

Toubou and Sahrawi

The main ethnic group found in the Tibesti region of northern Chad and southern Libya is the Toubou (or Tibou or Tebu). For centuries the nomadic Toubou were as little known to outsiders as their homeland, the secluded massif in northern Chad that still receives fewer visitors than any other part of the desert. For this reason, many older references to Ethiopian or Sudanic races in all likelihood actually apply to the Toubou. As the great 1911 edition of the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

states, “The allusions by classical writers to Ethiopians as inhabitants of the Sahara prove little, in view of the very vague and general meaning attached to the word.” The same entry on the Sahara goes on to observe: “The Tibbu (q.v.) or Tebu, once thought to be almost pure negroes, proved when examined by Gustav Nachtigal in Tibesti, where they are found in greatest purity, to be a superior race with well-formed features and figures, of a light or dark bronze rather than black. .. Physically, the Tibbu appear to resemble somewhat the Tuareg.”

Long separated from the main Chadian Empires such as Kanem-Bornu, which grew up around Lake Chad, the Toubou were historically ignored by the country’s centre. When the French ruled Chad, which was only one part of French Equatorial Africa, the situation was not radically altered. With limited resources to police the enormous northern expanses of the country, French authorities were forced to reach an unspoken, mutually beneficial understanding with the Toubou; the French would not interfere with the Toubou as long as the Toubou did not attack their camel caravans or outposts.

Saharawi women in a refugee camp

Sahrawi is an Arabic word that means “people of the Sahara’ or “desert people”. The term is most commonly used by and for the people of Western Sahara, and usually carries nationalist connotations for the people of that country which has yet to achieve independence. Sahrawi is not, however, transposable for a citizen of Western Sahara, a colonial-era border which would have been meaningless to the people - as is the case for all Saharan borders - before the arrival of European mapmakers. Inaccurately, Sahrawi has now become almost synonymous with the Western Sahara, what the UN calls one of the world’s last major non-self-governing territories. Sadly, this has become the rather negative defining characteristic of the region’s inhabitants: a landless people, refugees waiting for a nation. Many self-identifying Sahrawis live in Morocco, Mauritania and Algeria, as well as migratory populations in Mali, Niger and beyond.

The people themselves are a mixture of indigenous, that is to say pre-Islamic Berbers, Moors, Arabs from the seventh and subsequent centuries and black African ethnic groups from the Sahel and West Africa, both willing migrants and slaves.

Like those Sahrawi who call an Algerian refugee camp home, many denizens of the Sahara today - Berber and Bedu alike - find themselves unemployed and without the prospect of work. The Sahara continues to support numbers of livestock farmers: shepherds tending their flocks of sheep and goats in close proximity to the oases and camels and their owners living further out, beyond the pale, in the desert’s more remote and wilder corners. Some, with the largest flocks or herds, can grow very rich in this line of business but many never rise beyond a basic, subsistence level, with a single animal providing a family as much wool, milk, and meat as it possibly can.

Apart from the farmers and those working in tourism, employment options in the desert are limited. Where oil and gas is found so too are jobs. However, many of these are for skilled workers, engineers and the like, leaving those with limited formal education, into which category most habitues of the Sahara fall, overlooked or unemployable. Looking to the future, planned projects such as solar energy plants seem unlikely to offer anything like the numbers of jobs needed among the desert natives. Instead, the more likely course of action is for the continued migration of young men out of the desert into the towns and cities, where the persistent belief is that the streets are paved with gold. The majority of those seeking work will realise that if they do find what they think is gold on the streets of Cairo or Lagos it is probably sand that has followed them out of the Sahara.