The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (16 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

By nature, the mood question was far more challenging than studying the ups and downs of VO

2

max. An added complication was that the investigation of human feeling had less political traction because it involved fewer scientists, received less funding, and had less institutional support than was the case with research into sports and physical training. The pool of candidates shrank further still when the focus was on such curiosities as yoga. The discoveries in that case could be quite serendipitous in nature, as with the Duke investigators.

Scattered groups of scientists nonetheless made notable progress in the course of the twentieth century. In recent years, their work has become more abundant and substantial. The field—after an early history of false starts and digressions—now appears to be coming into its own.

The trend is significant. In the end, it may elucidate one of yoga’s most important benefits.

MOODS

S

at Bir Khalsa chatted amiably as we walked down the street. His beard was long and gray, his turban white, and his bracelet made of steel—all signs of his Sikh religion. He was not, however, Indian. Born in Toronto of European stock, he had converted to Sikhism decades ago upon taking up Kundalini Yoga, an energetic form that emphasizes rapid breathing and deep meditation.

No one on Longwood Avenue seemed to give the turbaned Sikh a second look. Boston that spring day was gorgeous. An early shower had scrubbed the air, leaving it awash in sunlight. Flowers and trees were blooming. Men and women were shedding their coats. People fairly hummed along the sidewalks.

We had just eaten lunch at Bertucci’s, a bustling restaurant where Khalsa had finished his meal with

bomba

—“the bomb” in Italian. The dessert consisted of balls of vanilla and chocolate gelato dipped in chocolate and covered with almonds, whipped cream, and chocolate sauce. I could see why his kids loved the place.

Maybe it was the sugar high, or the beautiful day, or the yoga. Whatever the cause, the air fairly pulsed as Khalsa—a faculty member at the Harvard Medical School and one of the world’s leading authorities on the science of yoga—laid out his findings and ambitions. The friendly man of fifty-six turned out to have a lot.

At Harvard, Khalsa had pursued a bold program of research that explored how yoga can soothe physically and emotionally. His focus was practical—and structured that way deliberately to demonstrate yoga’s social value. He had examined how its powers of unwinding can promote sleep and ease performance anxiety among musicians, and was now organizing a study to see if its calming influence could help high school students better fight the

blues and everyday stress. Khalsa had ten yoga investigations in various stages of development.

With energy and articulate zeal, he described his research as a way to help yoga break from its fringy past and go mainstream.

“What ever happened to mental hygiene?” he asked rhetorically. “It doesn’t exist—and never did. When you went through high school, you were never taught how to deal with stress, how to deal with trauma, how to deal with tension and anxiety—with the whole list of mood impairments. There’s no preventive maintenance. We know how to prevent cavities. But we don’t teach children how to be resilient, how to cope with stress on a daily basis.

“There’s a disconnect,” he continued. “We’ve done dental hygiene but not mental hygiene. So the question is, ‘How do we go from where we are now to where we need to be?

’

”

Khalsa argued that the only way to convince people about the value of yoga and establish a social consensus that encouraged wide practice was to conduct a thorough program of scientific research. He added that recommendations for regular toothbrushing had started that way and illustrated the potential value of good yoga studies.

“That’s my mission in life,” Khalsa told me.

This chapter examines not only Khalsa’s research but many inquiries into how yoga can lift moods and refresh the human spirit. It starts with the earliest research and ends with the most recent. The arc of the narrative is really a detective story. The studies began with the muscles (and how yoga can relax them), went on to study the blood (and how yoga breathing can reset its chemical balance), and eventually zeroed in on the subtleties of the nervous system (and how yoga poses can fine-tune its status). The discipline was found to lift and lower not only emotions but also their underlying constituents—the metabolism and the nervous system.

The mood benefits detailed here are very real, unlike some of the aerobic claims of the last chapter. But the field also has its popular myths. They tend to be outright errors, probably rooted in ignorance rather than subtle shadings of the truth done with profit in mind.

Psychologists tell us that a fundamental building block of emotional life is strong feeling, such as fury or affection. By definition, moods are considered less intense, more general, longer lasting, and less likely to arise from a particular

stimulus. They are seen as drawn-out emotions. For instance, joy over a period of time produces a happy mood. Sadness over time results in depression. Unlike sharp feelings such as rage or surprise, moods tend to last for hours and days, if not weeks. If intense, they can color our life perceptions—at times dramatically.

Moods are central to meaning in life and thus, in the judgment of psychologists, more important than money, status, and even personal relationships because they affect the happiness quotient that we assign to life activities. As the saying goes, a rich man in a bad mood can feel destitute, and a poor man in a good mood rich beyond words. To a surprising degree, moods define our being.

It turns out that the word arose in the earliest days of the English language and that its first definitions resonate with existential import. “Mood” was originally a synonym for “mind.” In Old English, the word

mod

meant “heart,” “spirit,” or “courage.”

An intriguing question that investigators have yet to address is whether yoga can change an individual’s pattern of moods—in other words, a person’s core emotional outlook. Can the regular practice of Sun Salutations produce a sunny disposition? Does yoga bring about what might be considered characteristic states of affability?

Many people have looked to their own experience on such matters and found that, overall, yoga lifts their emotional life. Significantly, the vast majority are women.

The conventional wisdom is that episodes of major depression strike women twice as frequently as men. The drug evidence is stark. A survey found women nearly three times as likely as men to take antidepressants—with usage as high as one in every four or five women.

If those characterizations are right, yoga should resonate strongly with women as a way of fighting the blues. I personally saw evidence of that attraction. In the early winter of 2010, I joined dozens of women (and a few guys) who had gathered to learn about using the discipline as a means of emotional uplift.

“It really saved my life,” Amy Weintraub told us during her introductory talk. “I wouldn’t be here.” It was Friday night at Kripalu, the yoga center in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts. Weintraub, author of

Yoga for Depression

, was leading a weekend seminar on mood management.

She came to her

calling after a life of crippling dejection and numbness. “I moved as through a fog,” she recalled in her book. “I lost keys, gloves, and once, even my car.” Antidepressants did little. Then she found yoga. The fog lifted. In a year, she was off drugs and soon became a yoga instructor. Her rebirth came with deep feelings of emotional strength.

At Kripalu, for three days, Weintraub marshaled every available weapon in the yoga arsenal to teach us how to seize control.

“You’ll be feeling lighter and brighter or your money back,” she said with a smile. Her methods were not particularly strenuous. But they all took aim with great precision at lifting the spirit. We relaxed. We visualized. We did balancing poses that forced us to shift our attention from mind chatter to the here and now. We laughed. We stretched. We made calming sounds. We did Breath of Joy—inhaling, bringing our arms slowly up to the sky, then exhaling with a breathy “Haaaa” while bringing our arms down rapidly. By the end of it, we glowed, lit from within.

Weintraub understood the science and told our class about a number of studies and researchers. It turned out that she knew Khalsa and was working with him on one of his investigations—to compare the benefits of yoga with those of psychotherapy. She also had a book in the works:

Yoga Skills for Therapists

.

All this may sound new and fresh. But it turns out that Harvard, Boston, and Massachusetts have long played host to individuals and institutions with abiding interests in yoga’s emotional sway. In fact, I suspect that is the core attraction of Kripalu, which has drawn waves of interest for decades and describes itself as the nation’s largest residential center for yoga and holistic health. The facility is located on hundreds of rural acres far from the usual pleasures and distractions of urban life.

On the Friday that I signed in—with the leaves of the trees gone and the area dappled in white from a recent snowfall—Kripalu succeeded in registering nearly five hundred guests for its weekend classes. The vast majority were women.

Thoreau characterized yogis as having no earthly care: “Free in this world as the birds in the air.” In 1849, he told a friend that he considered himself a practitioner—the first known instance of a Westerner making that claim. “I would fain practice the yoga faithfully,” Thoreau wrote. “To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a yogi.”

At Harvard, his alma

mater, William James looked favorably on yoga as a means of mental regeneration. The famous psychologist, trained as a medical doctor, zeroed in on one of yoga’s most basic exercises—the simple but systematic relaxation of the muscles.

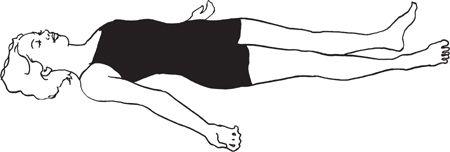

The pose is called Savasana, from

sava,

the Sanskrit word for “dead body.” Today we call it the Corpse. It is the easiest of yoga’s positions. Rather than twisting or stretching, students simply lie on their backs, eyes shut, and let their arms, legs, and other body parts go limp. In this state of repose, students relax their muscles as much as possible, entering a condition of deep rest. It is usually done at the end of a yoga class and seems to have been around for centuries.

Corpse,

Savasana

James, in his 1902 book,

The Varieties of Religious Experience

, identified that kind of letting go as “regeneration by relaxation” and suggested that it could not only revitalize the spirit but advance the more ambitious goal of fostering healthy life attitudes. “Relaxation,” he wrote, “should be now the rule.”

A graduate student paid close attention. His name was Edmund Jacobson. A physiologist, he had come from Chicago to work on a doctoral degree at Harvard. The gospel of relaxation caught his eye and, following the lead of James and other professors, he threw himself into an experimental study. It focused on the startle reaction—in particular to how subjects reacted when a strip of wood was slapped down on a desk with a sudden

crack.

To his surprise, Jacobson found that relaxed subjects had no obvious reaction. He surmised that deep relaxation caused mental activity to drop.

Jacobson tried relaxation himself. Like many students, he suffered bouts of insomnia. But

in 1908 he taught himself how to relax and found that the lessening of muscular tension let him enjoy a good night’s rest.

Jacobson became a convert. Upon taking a job at the University of Chicago, he pursued an ambitious agenda of research and treatment, more or less founding the medical field of trained relaxation. His books included

Progressive Relaxation

(1929) and

You Must Relax

(1934), which went through more than a dozen printings and editions.

Jacobson would have patients close their eyes and tense and relax a body part, concentrating on the contrast. In time, they would get the hang of reducing the tension. Jacobson claimed that his method produced remarkable cures, eliminating everything from headaches and insomnia to stuttering and depression.

To satisfy his own curiosity—and to convince skeptics of the method’s importance—Jacobson worked hard to gather a body of objective evidence. His goal was to develop a machine that would let him track tiny electrical signals in the muscles and measure subtle currents of a millionth of a volt or less. In his efforts, Jacobson got considerable aid from Bell Telephone Laboratories—then the world’s premier organization for industrial research, which in time won a half-dozen Nobel Prizes. The collaboration between medical doctor and industrial giant resulted in innovations that foreshadowed the electromyograph, a medical instrument that records the electrical waves of skeletal muscles.