The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (9 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

Triangle,

Utthita Trikonasana

Drawing on such insights,

Iyengar became a master of precision. Good alignment became his signature. He learned much about what was reasonable, what was ambitious, and what was dangerous.

Gune, who had become chairman of the Board of Physical Education in the Bombay region, saw Iyengar perform around 1945 in a public demonstration. History gives no details of the encounter between the two men—two pioneers who sought to align Hatha yoga with modern science. It does note, however, that Gune arranged for the institution where Iyengar performed to receive a financial grant.

In 1947, India won independence and the nation’s powerful no longer promoted yoga as a way to build Hindu pride. Patronage ended or fell dramatically. In the mountains south of Bombay, Gune’s ashram tightened its belt, uncertain of the future. In Mysore, politicians took over for the royal family.

Coincident with this plunge in domestic support, Hatha yoga went global. The exports began with a gifted student who had studied with both Gune and Krishnamacharya. Like Iyengar, the neophyte had come to yoga for reasons of ill health and had become a fervent champion of its restorative powers. Moreover, the student was a vivacious woman. She helped turn Gune’s observations about yoga being “peculiarly fitted for the females” into multitudes of women devotees.

Born of a Swedish bank director and a Russian noblewoman, Eugenie Peterson (1899–2002) was a rising Indian movie star with the stage name Indra Devi when she developed a serious heart condition. She met Gune and studied at his ashram, likening it to a health spa. Devi found herself in classes with other women and distraught at her poor flexibility. A woman instructor advised patience.

The neophyte then sought to study with Krishnamacharya.

He refused.

“He said that he had no classes for women,” Devi recalled.

She persisted.

Eventually the guru relented.

Devi learned well, moving to Hollywood in 1947 and teaching such celebrities as Gloria Swanson, Greta Garbo, and Marilyn Monroe. She became known as the first yoga teacher to the stars.

Devi gathered her insights

into a 1953 book,

Forever Young, Forever Healthy.

It became Hatha yoga’s first bestseller and the first to widely popularize the vision of ultimate health, quickly going through sixteen printings. It spoke especially to women, its tone intimate, its pages rich in fitness and beauty tips.

As yoga soared in popularity, science dug into an aspect of the old agenda that had managed to endure—veneration of the miraculous. Big claims, despite a number of exposés, had grown more prominent.

The star was Yogananda. The name of the charismatic swami meant “bliss through divine union.” His book,

Autobiography of a Yogi

, told of his personal experience with yogic supermen who could fly, change the weather, read minds, walk through walls, materialize jewels, and, of no small importance to meditators in the woods, make clouds of mosquitoes suddenly disappear. It was Aladdin come true. His book, translated into dozens of languages, awed and inspired a generation of seekers. “Control over death,” he declared in his writings, echoing the

Hatha Yoga Pradipika

, “comes when one can consciously direct the motion of the heart.” In his

Super Advanced Course

, Yogananda gave the ostensible secret: “Yogis know how to stop heart and lung action voluntarily but keep physically alive by retaining some Cosmic Energy in their bodies.”

Into this supernatural blur came something entirely new in the world of yoga exposés—a defector, a true insider who knew the field’s secrets and personalities and perhaps its vulnerabilities.

Basu Kumar Bagchi (1895–1977) had grown up in Bengal, like Paul, and had enjoyed a close friendship with Yogananda. The two men went to college together, took monastic vows together, ran a school together, came to America together, preached together, and published religious tracts together. Bagchi became the second-in-command of a rising spiritual enterprise that Yogananda founded in Los Angeles. The Self-Realization Fellowship came to own many costly properties, including more than a dozen lush acres of California coastline.

The two eventually fell into bitter conflict, allegedly over Yogananda’s breaking his vow of celibacy with female devotees. Bagchi gave up his monastic vows and earned a doctorate in psychology. After a stint at Harvard, he took a post at the University of Michigan and became a pioneer in deciphering brain waves for the diagnosis and treatment of disease, including epilepsy. Bagchi

wrote little or nothing about yoga during this period. It was his past, not his future.

Then Yogananda died. It happened in 1952 while the famous swami was giving a talk at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles. He suffered a heart attack and collapsed, his death reported on the front page of the

Los Angeles Times.

His demise at the age of fifty-nine seemed to kick the Self-Realization Fellowship into high gear. Yogananda became a departed saint. Hagiography flourished. The group released portraits of the departed yogi that fairly glowed with saintly radiance.

Bagchi now dug in. Over the course of a decade, he investigated one of the most palpable of the miracles—stopping the heart.

Bagchi recruited colleagues, won financial backing from the Rockefeller Foundation, bought the best equipment, traveled to India, visited Gune’s ashram, and studied some of the world’s most gifted yogis. To his delight, he eventually tracked down Krishnamacharya—the guru to the gurus who founded the main schools of modern yoga. The celebrated man had become a living testament to yogic wonders. To win converts, Krishnamacharya had taken to demonstrating what his devotees hailed as siddhis—suspending his pulse, stopping cars with his hands, lifting heavy objects with his bare teeth.

When first approached to perform the siddhis, the yogi protested. He was sixty-seven and too old. Finally, he relented. Bagchi hooked up the electrodes as the venerated yogi closed his eyes and concentrated.

Blip, blip, blip.

The recording pens flew back and forth, catching the subtle cardiac rhythms no matter how hard Krishnamacharya tried. Yes, the heartbeat was diminished. But even a quick glace at the tracing paper showed that the beat was still there, even if reduced and too faint for a stethoscope to pick up. The heart was still thumping away inside,

blip, blip, blip.

In 1961, Bagchi and his colleagues published their findings in

Circulation

, the prestigious journal of the American Heart Association.

“It was often reported that some yogis could stop the heart,” he later recalled. “Everybody including physicians thought that it was so. We discovered the truth.”

Another insider joined in. He was no defector but rather a central authority in the world of yoga and one of its most respected elders.

Gune at that point was approaching his eightieth birthday, white hair spilling down his neck

in curls. The cardiac studies caught his attention. After all, some of his colleagues had participated. Bagchi had stayed at the ashram much longer than anywhere else in India—more than five weeks. What the foreign scientists had come to examine and—as it turned out, to rebut—was not some trifle but a central tenet of yoga and its legacy of superhuman achievement. It put the ashram in an awkward position.

A lesser man might have denied the heart findings or disparaged them as flawed. Not Gune. Not the nationalist rebel who vowed to make no statement “without having scientific evidence to support it.” So he rallied his ashram. And—to his immense credit—he did so not with reluctance or diffidence, but boldly. It was as if he, late in life, became determined to enhance the reputation of his institution and mission. Bagchi and his team had focused on the heart. Gune would take on an even bigger challenge.

Live burial was the most spectacular way that gurus and adepts had worked in public to reveal their otherworldly powers, as the Punjab yogi had demonstrated for the king.

Gune put his team into creating a samadhi pit meant to mimic the earthen dens of the miracle workers. But it was designed to minimize the chance of extraneous variables—not to mention cheating. It was dug not in a field or in sand, as yogic supermen often did, but in the foundations of a laboratory, where gas flows would be easier to monitor and eliminate. It measured six feet long, four feet wide, and four feet deep, its floor plaster, its walls brick, and everything coated in thick paint. The team installed a seal around the door to make it airtight. The precautions produced a samadhi pit that was completely sealed off from the outside world—the first of its kind. No air could enter or exhalations leave.

The ashram took volunteers from its own ranks and beyond. The most gifted turned out to be an itinerant showman of athletic build who had performed yogic feats at country fairs. He boasted of having endured live burials for up to a month. The showman, Ramandana Yogi, wore bangles on his wrists and trunks of tiger skin.

Twice in 1962 he braved the pit. The first time he managed to withstand the chamber not for anything approaching forty days and forty nights—not even for a month or a week. He went eleven hours. His second try was better. He went eighteen hours before demanding to be let out, gasping for breath.

In all, the scientists

locked volunteers into the samadhi pit eleven times. Nothing like it had ever been done before. The results tore a hole in yoga’s legacy of miraculous claims.

Today the ashram has a slightly dilapidated air, walls crumbling here and there amid dense foliage. But the pit is frozen in time, bright and spotless and ready for any new volunteer who might appear. It is part museum, part open challenge.

“We’re still ready to do this,” said Makrand Gore, a senior researcher at the ashram. He opened the pit’s door while describing its past. The tidy den, well lit and brightly painted, did in fact seem ready to admit a new volunteer. A bundle of wires hung down from its ceiling, awaiting a miracle worker.

Gore’s boss, T. K. Bera, a small man with a muscular presence, joined the tour. He said the ashram had looked hard for siddhis over the decades but had found no miracles—none, try as it might.

“People say yoga is black magic,” Bera remarked. “But what we’ve found is that it gives the power to live on a reduced metabolism. That’s all. It’s not magic.”

Popular yoga made no explicit acknowledgment of the pit demythologizing but continued to shed the old emphasis on magic and eroticism. The trend culminated with Iyengar.

His 1965 book,

Light on Yoga

, quickly became the how-to bible of Hatha yoga. Around the globe, it sold more than a million copies, confirming the field’s export potential. In his preface, Iyengar poked fun at credulous people who asked if “I can drink acid, chew glass, walk through fire, make myself invisible or perform other magical acts.” Instead, he described his objective as portraying yoga “in the new light of our own era.”

Iyengar made no mention of Gune, Bagchi, the humiliation of his own guru, Krishnamacharya, or the coaching of his scientific tutor, Gokhale. He simply infused his book with the new sensibility.

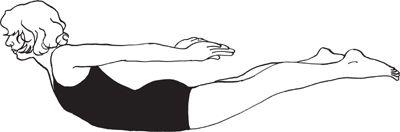

For every posture, he noted a number of invisible health effects, often using medical terms. An example was the Locust, or Salabhasana. The student lay facedown and lifted the head, chest, and legs as high as possible. Iyengar said the pose “relieves pain in the sacral and lumbar regions” while benefiting “the bladder and the prostate gland.”

Locust,

Salabhasana

So too he praised the Headstand.

Its upending of the body “makes healthy pure blood flow through the brain cells” and “ensures a proper blood supply to the pituitary and pineal glands.” Iyengar never said anything about research or clinical trials or the possibility of placebo effects. Instead, he piled on the medical terms and laid out the health benefits, giving his book a feeling of scientific authority while avoiding the messy issue of evidence. It was

light

with no explanation of its origin.