The Secret Life of Uri Geller (26 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

‘He was in his apartment in the same building, so I phoned him, and he came up and said he didn’t do anything. We both had to lift it and put it back in the bedroom, and as we came out from the bedroom, the lamp that was in the lounge started rattling and moving, I had a little marble frog in my bedroom, and all of a sudden, it fell through the wall from my bedroom into the main room. It actually went through the wall. I saw it do so. Then a chair that was in the lounge turned around and fell in front of us, and Uri started not so much panicking, but he was a little concerned. He said, “Yasha, I have to write this down, can you get me a Coke.” And I went into the fridge, and as we opened it, a pencil came out of the can.

‘Another time, we went to a gala opening on Broadway for a show called

Via Galactica.

We were sitting there, and Shipi, myself and another Israeli friend of ours were next to Uri. I noticed that there was no arm between our two chairs, and Uri didn’t feel very comfortable, so I put my jacket down, and he put his arm on it. We went out and it was pouring with rain and our car was parked in a garage. While I got it, they went into a telephone booth to keep out of the rain. On the way to collect the car, I saw something floating in the air – floating, not falling. It slowly dropped down. I picked it up and I saw it was the arm of the theatre chair. I still have it. The funny thing was that, although it landed in a puddle, it was completely dry.’

LONDON CALLING

C

oming for the first time to Britain in November 1973 and appearing with consummate success on a television chat show hosted by David Dimbleby was the beginning of Uri Geller’s journey to what would become home. He had been brought up on stories of his father’s exploits in the British Army, before he became an Israeli soldier, and he, Uri, had enjoyed a traditional British education to the equivalent of today’s GCSE level in Cyprus. A decade later, he would settle in Britain, where he has now lived for over 30 years.

At times, the live Dimbleby show looked as if it would be a damp squib, like a famously abortive Johnny Carson TV appearance Uri would later make in the States. On the Dimbleby show, it took an agonizingly long period of silence, with Uri concentring hard but nothing at all happening, before things started to work in the studio – and a Geller furore was unleashed in Britain.

The reason for the uproar and excitement was that Uri had, in one jump and without having specifically planned to do so, taken his unique form of psychic entertainment-cum-education to a whole new level. He was the first person to demonstrate a scientific (or paranormal) effect – what we would now call ‘interactively’ – with the public at home being asked to find broken and stopped watches and clocks as well as ordinary spoons, to see if the timepieces started and the spoons bent. In this, and subsequent TV demonstrations, tens of thousands of people reported strange happenings in their own homes, and TV stations’ switchboards becoming jammed with callers became the norm. (Today it would be a Twitter storm, of course.)

The Dimbleby show was a most important event for Uri, both in that it opened Britain up to him, and it helped him develop a new perspective on what it was he was actually doing. ‘What you can’t take away,’ he says, ‘is, let’s say 10,000 phone calls come in to a TV show from people saying their spoons bent or their watches restarted or something else strange happened. And let’s imagine that 50 per cent of them were lying. And let’s say half of the remaining 5,000 imagined it. What I want to know, and what I’ve wondered all these years, is what about the rest? What about the other 2,500, or the 1,000, or the 500 or the 50 that weren’t imagining and weren’t lying or self-deluding? How does it work for them? I honestly don’t know, I don’t really think I want to know, and I’m not sure the Universe wants us to know. I don’t believe we’re ready for it.’

The new idea he formed as a result of the Dimbleby phenomenon, which was repeated regularly on shows in other countries, was that he was not the person affecting the metal, he was an enabler. ‘I thought I was doing it by staring into the camera, but it wasn’t that. Later, an American psychologist interested in Uri, Professor Thelma Moss of the Neuropsychiatric Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, called him to say she had managed to get students to start stalled watches and so on by watching a video of him. The idea that even a recording of him could work as a catalyst to unleash something everyone has was a matter of some concern to Uri; if anyone could do this, wasn’t he going to put himself out of a job before long?

Probably the most ringing endorsement of Uri in the immediate aftermath of his appearance on the Dimbleby show was that of the science writer Brian Silcock of

The Sunday Times

, who in the next edition of the newspaper, described an encounter with Geller in a taxi as, ‘leaving this initially highly sceptical science correspondent with his mind totally blown.’ Geller had caused Silcock’s thick office key to bend in the flat belonging to photographer Bryan Wharton, who was holding it in his hand. He also made a paperknife bend, and Silcock and Wharton both saw it go on bending.

‘It is utterly impossible to remain sceptical after seeing Uri Geller in action,’ Silcock wrote, adding, ‘I am convinced that Geller is a telepath too,’ after Uri had reproduced pictures that the journalist was only thinking of, but had not drawn. (Over the years that followed, Silcock semi-reversed his opinion. ‘I became convinced in my own mind that it was just a conjuring trick,’ he told the author. ‘I have no idea how the trick was done, but I think there was a process of my natural scepticism reasserting itself. I tend to be of a rather sceptical, downbeat frame of mind, and I somehow got shoved out of it. I don’t really understand how that happened, either.’)

Perhaps the difference between failure on NBC’s Johnny Carson Show and success on the BBC’s Dimbleby show can be put down to the different attitudes of the two hosts. Carson was a devout sceptic, who, it is claimed, had got the Geller-obsessed magician James Randi to rig the studio against any possibility of Uri cheating. Dimbleby (now one of Britain’s senior political commentators), although a sceptic, had been quite shaken before the show to see a key he was holding bend under Geller’s gaze, and once the cameras were on, he was clearly in an encouraging, positive frame of mind.

Also present on the BBC show as a scientific sceptic was John Taylor, an expert in black holes, who was Professor of Applied Mathematics at London’s, King’s College, and previously a Professor of Physics at Rutgers University, New Jersey. The writer on anomalous science, Lyall Watson, (author of

Supernature

) was also on hand to explain that he had wasted his first experience of Geller by looking all around him for the catch. There were, Watson pronounced, no tricks involved with Uri.

Uri was his usual engaging self, and said although he was convinced that his abilities were caused by some ‘outside power’, what he did might equally be powered by the people around him. He went on to do a successful telepathy test, which drew gasps from the audience, and to wreak havoc with some BBC canteen cutlery. He also caused the hands on Watson’s watch to bend under the glass while he was still wearing it, an effect Uri had not seen since he was a schoolboy.

Today, Dimbleby still clearly recalls the show as a huge success, and explains his view on Geller today – as well as possibly the view of much of the British intelligentsia – with characteristic crispness. ‘I saw him doing the metal bending several times with Yale keys, and I can only say what I saw,’ Dimbleby says. ‘He would take a key and rub it between his first finger and thumb, then put it down and hold his hand over it, and it sort of lifted up towards his hand. I saw it lift up. Once it snapped and once it was just completely bent in half. I am very pragmatic about these things I don’t know what the rubbing consisted of and what happened during that process.

‘The conjurer who rubbished him on telly afterwards, Paul Daniels, [today a good friend of Uri] said everyone had been conned and it was just sleight of hand,’ Dimbleby added, ‘But it was clear to me that what wasn’t sleight of hand was that the key was on a table or in the palm of his hand, or sometimes being held by the person who had proffered it. I certainly saw the key moving without his actually touching it two or three times. He did telepathy on the programme quite impressively, and I have never seen anyone simulate properly the key bending or forks drooping and seeming to melt in his hand.’

Professor Taylor was entranced by what he saw in the BBC studio; ‘I believe this process. I believe that you actually broke the fork here and now,’ he said on the show, in a mixture of delight and bafflement. He took Uri off for testing at King’s College, and became an enthusiastic Geller supporter. One scientific colleague recalls Taylor having in his eyes the obvious gleam of someone who could see himself getting a Nobel Prize for discovering a new scientific principle that would explain Uri Geller’s abilities.

Taylor wrote a popular book,

Superminds: An Enquiry into the Paranormal

, largely about Geller and dozens of children – known as mini-Gellers – who were discovered in Britain after the Dimbleby show to have similar metal-bending abilities. For a few years, the names Taylor and Geller were almost uttered in one breath in the country. But then Taylor underwent a change of mind on Uri and the entire paranormal field. He published another book in 1980,

Science and the Supernatural

, a sort of antimatter version of

Superminds

, in which he concluded that the evidence for paranormal spoon bending was ‘suggestive but certainly not watertight.’

Far less noisily in the background, however, a perhaps rather more qualified British academic – more qualified in that he was an experimental physicist – was working intensively with Geller in his laboratory in London as well as at his home in Sunningdale, Surrey. John Hasted, who held the chair in Experimental Physics at Birkbeck College, was a most unusual scientist. As well as being a world authority on his speciality, atomic collisions, he was a lifelong lover of folk songs, was deeply involved in the London skiffle scene in the 50s and 60s, and was an early activist in the nuclear protest movement, who had gone on the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’s first Aldermaston march in 1958. Hasted was also involved in the first pirate broadcasting in Britain, a CND operation that ran from 1958 to 1959, in which transmitters were set up on the top of buildings to put out tapes of speeches by Bertrand Russell.

Hasted retired to St Ives, Cornwall, and when the author interviewed him, he was living in a bungalow overlooking the lighthouse Virginia Woolf wrote about in her famous novel. Frail, but mentally extremely agile, Hasted was still very much into peace, as well as being an enthusiastic vegetarian and a voracious reader, devouring everything from new scientific papers to Martin Amis to classics. In the 1970s, Hasted stuck his neck out and, after exhaustive laboratory tests centring on his use of mechanical strain gauges to measure accurately the bending in metal, proclaimed Uri Geller genuine. In 1981, his book

The Metal-Benders

, almost 300 pages of scientific data, speculation and anecdote, he set out his experiences with Uri and some of the child spoon benders he found, along with his theories on the phenomenon. To the end of his life, he believed strongly in paranormal metal bending, although he regarded the work he did as a comparative failure, because he never managed to work out for certain how the phenomenon worked.

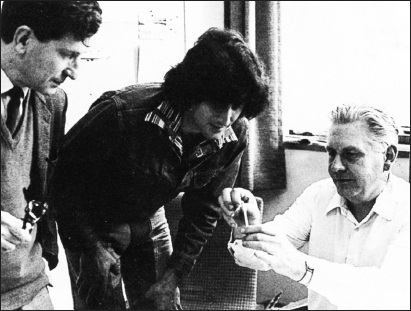

‘If people say Uri Geller is a magician, they have simply failed to read the published scientific evidence,’ Hasted said on a leaden, winter Cornish day, looking out across the beautiful St Ives Bay, which was shrouded in a mist that blanked out the Godrevy Island lighthouse. He explained how he had been introduced to Geller by Professor David Bohm, the renowned American-born theoretical physicist, who was interested in the links between eastern mysticism and modern physics, an interest he shared with Russell Targ and others. Bohm, a member of the top-secret Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb, and a friend of Einstein, was pretty well convinced that Geller was genuine. Hasted, while fascinated by, as he puts it, ‘the nine-tenths of science which is unknown’ had no experience of the paranormal or psychic phenomena. Even so, after meeting Geller, he was soon convinced that he was genuine.

‘I never had to be concerned that I was imagining seeing spoons bend,’ he explained, ‘because right from the very start I insisted on instruments, quite correctly of course. [The magician] Randi came to see me at Birkbeck. He was absolutely fanatical about this, but he was not very convincing. It took me about a minute before I saw how he did it, by pre-stressing the spoon. He is back in the days of bending spoons by using force, you see, but he has never attacked my more important experiments, the ones with instruments, because he doesn’t understand instruments. I don’t think he could have duplicated even the first experiment in Uri’s hotel when I first went with Bohm, because I brought my own key, and I had identified it by weighing it very carefully – and I didn’t let Uri see it until I popped it on the table. He started to stroke it, and eventually it bent – not a lot, but it bent.

‘I found these

professional

sceptics to be every bit as much a menace to scientific truth and impartial observation as the worst psychic charlatans,’ the professor continued. ‘They write that researchers in the parapsychology field are emotionally committed to finding phenomena, yet forget conveniently that they themselves are emotionally committed to finding there are no phenomena. I was often reminded of a northern saying: “Them as believe nowt, will believe ’owt.”’ [Which is to say, “people who refuse to believe anything are often the most gullible.” Hasted was referring to the way he found that sceptics could be, ironically, convinced by the kookiest conspiracy theory if it bolsters their scepticism.]