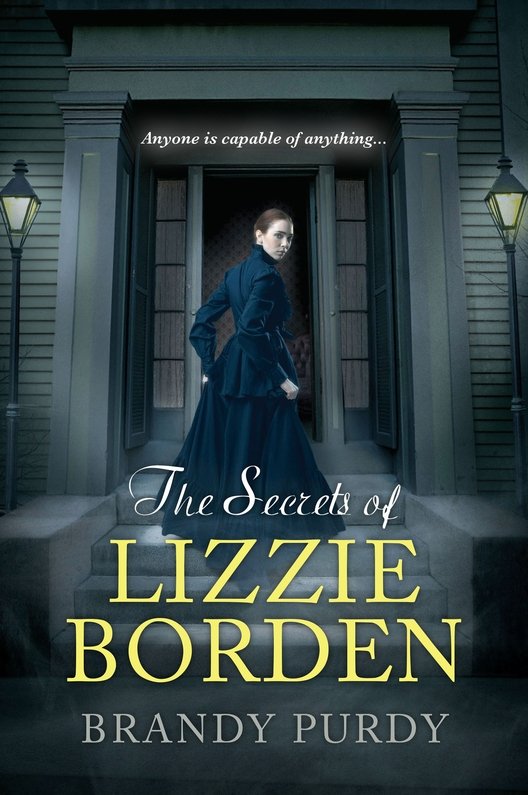

The Secrets of Lizzie Borden

Read The Secrets of Lizzie Borden Online

Authors: Brandy Purdy

Books by Brandy Purdy

THE BOLEYN WIFE

Â

THE TUDOR THRONE

Â

THE QUEEN'S PLEASURE

Â

THE QUEEN'S RIVALS

Â

THE BOLEYN BRIDE

Â

THE RIPPER'S WIFE

Â

THE SECRETS OF LIZZIE BORDEN

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

The Secrets of

LIZZIE BORDEN

LIZZIE BORDEN

BRANDY PURDY

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

AUTHOR'S NOTE

This is a work of fiction inspired by the life of Lizzie Borden and the murders forever linked to her name. It should not be read as a factual account. For those interested in the known facts and various theories, I have included some suggestions for further reading at the end of this novel.

In this world there are only two tragedies.

One is not getting what one wants.

The other is getting it.

One is not getting what one wants.

The other is getting it.

âOscar Wilde

Â

More tears are shed over answered prayers

than unanswered ones.

than unanswered ones.

âSaint Teresa of Avila

Â

The truth shall set you free.

âJohn 8:32

Chapter

1

1

I

awoke from the dream, wishing, as I always did, that it would vanish right away without lingering to torment me, or, better yet,

never

come to visit me again. I

hated

it! And I didn't want

anything

to spoil this special day I had been looking forward to for so many months. But it had already begun to work its evil spell. Curiously, it often came as a herald to announce the coming of my monthly blood, and this time was no exception. It was as though those

terrible

long-ago memories of the smell of fresh-spilt blood, my bare feet slipping and sliding in it, my bottom thudding down to sit in it, and feeling it soaking through my skirts and drawers seemingly into my very skin, enticed the blood to flow from my own body. How I

hated

it. The blood and the memories so intricately bound they could never be divided.

awoke from the dream, wishing, as I always did, that it would vanish right away without lingering to torment me, or, better yet,

never

come to visit me again. I

hated

it! And I didn't want

anything

to spoil this special day I had been looking forward to for so many months. But it had already begun to work its evil spell. Curiously, it often came as a herald to announce the coming of my monthly blood, and this time was no exception. It was as though those

terrible

long-ago memories of the smell of fresh-spilt blood, my bare feet slipping and sliding in it, my bottom thudding down to sit in it, and feeling it soaking through my skirts and drawers seemingly into my very skin, enticed the blood to flow from my own body. How I

hated

it. The blood and the memories so intricately bound they could never be divided.

I have always claimed to have no memories of my mother, Sarah Morse Borden, who died when I was only three years old, but that is not true. Sometimes it is easier to tell a lie. To say

No

closes the door on the conversation, whereas saying

Yes

flings it open wide and invites further inquiry and to slam and bar it then is to be branded

rude

and

inhospitable

.

No

closes the door on the conversation, whereas saying

Yes

flings it open wide and invites further inquiry and to slam and bar it then is to be branded

rude

and

inhospitable

.

There are actually three things I remember about my mother.

The first is her appearance, her Gypsy-black hair and deep-set dark eyes, brooding and mysterious, the kind of eyes you could imagine intently scrutinizing a spread of tarot cards, shrewdly divining their secrets. Perhaps these recollections owe more to photographs than actual memories; I only know that she had such a stabbing deep stare that to even look at pictures of her makes me uncomfortable, as though her eyes could bore right through my skull and read every thought inside my head plain as words printed on the page of a book. Had she lived, I doubt I would have ever been able to keep a secret from Mother. As awful as it sounds, sometimes just the sight of those sharp, piercing eyes makes me feel relieved that she died before I had any secrets worth keeping. It is disconcerting at times just how much my sister, Emma, with her dark hair and prying and intrusive eyes resembles her; only the full, womanly curves are lacking. Emma is as skinny as a starving bird, with shoulder blades like scalpels.

The second thing I remember about Mother is her clothes. Everyone said she had the fashion sense of a color-blind gypsy. She loved to wear bright colors, fussy, bold, and garish prints in which violent wars raged perpetually between the shades, and fancy fringed shawls and flowered hats and bonnets the louder and livelier the better, and a crude string of coral beads she clung to religiously, superstitiously convinced that they would ward away all evil.

Maybe it was simply that she didn't know any better. She was after all just a poor farm girl who had the good fortune to attract a prosperous undertaker, and there was no mother- or sister-in-law to take her hand and gently guide her in the direction of good taste and refinement. My father, Andrew Jackson Borden, was a tenacious, bull-headed Yankee businessman who knew nothing, and cared even less, about fashion, only what it cost him. But Mother knew how to make the most of a cheap dress goods sale, it was

amazing

how far she could stretch a dollar at such events, and Father felt blessed to have such a thrifty wife who could bargain a bolt of mauve and orange flowered calico that no one else seemed to want down from a nickel a yard to three cents. And her Sunday best bonnetâa wide-brimmed red-lacquered straw hat adorned with red and green wax tomatoes and a wild spray of sunny yellow dandelions and white meadow daisies sprouting like weeds, cherry-red and apple-green ribbons, and a lace curtain veilâbought on a rare trip to Boston, Father often recounted with great pride, she regarded as her greatest triumph won at only 75¢. If the tomatoes had been real instead of waxen, he always said, they would have rotted long before she bartered its freedom from the milliner's window where it had been languishing the better part of a year. It was the ugliest and loveliest hat I ever saw.

amazing

how far she could stretch a dollar at such events, and Father felt blessed to have such a thrifty wife who could bargain a bolt of mauve and orange flowered calico that no one else seemed to want down from a nickel a yard to three cents. And her Sunday best bonnetâa wide-brimmed red-lacquered straw hat adorned with red and green wax tomatoes and a wild spray of sunny yellow dandelions and white meadow daisies sprouting like weeds, cherry-red and apple-green ribbons, and a lace curtain veilâbought on a rare trip to Boston, Father often recounted with great pride, she regarded as her greatest triumph won at only 75¢. If the tomatoes had been real instead of waxen, he always said, they would have rotted long before she bartered its freedom from the milliner's window where it had been languishing the better part of a year. It was the ugliest and loveliest hat I ever saw.

The third, and last, thing I remember about my mother is her blood. The blood that came every month was a time of terror for us all. Father tore at his carroty-red hair and whiskers with worry yet tried to keep his distance, disdaining anything to do with “female matters,” preferring the company of corpses instead during what he privately called “hell week,” and busying himself with his never-ending, all-consuming pursuit of the almighty dollar. Money was Father's religion, his muse; it occupied his thoughts all day and his dreams all night. He rarely willingly parted with his hard-earned dollars unless he was sure he could make them breed like green rabbits. And my sister, Emma, ten years older than myself, was at school for most of the day, so I was left alone at home with Mother.

Mother

hated

the monthly blood. No medicine could soothe her. She would throw the bottles at the wall when they failed her, devil-damning the false promises printed on their labels. She would crouch down upon the floor, bracing her back against the wall, and howl like a mad dog at the moon, rocking, crying, and

screaming

as the blood oozed out and the cramps seized her. Demons, she insisted, were trying to crush her skull; she could feel their talons digging in, and making wild displays of colored lights dance before her eyes. She would

rage

against God for unfairly visiting this curse upon

all

womankind to punish

one

woman's sin. How my mother

hated

Eve! If a preacher mentioned her in a sermon, Mother would stand up, slash him with the daggers of her eyes, and stomp out of the church as though she were crushing a detested enemy with every step.

hated

the monthly blood. No medicine could soothe her. She would throw the bottles at the wall when they failed her, devil-damning the false promises printed on their labels. She would crouch down upon the floor, bracing her back against the wall, and howl like a mad dog at the moon, rocking, crying, and

screaming

as the blood oozed out and the cramps seized her. Demons, she insisted, were trying to crush her skull; she could feel their talons digging in, and making wild displays of colored lights dance before her eyes. She would

rage

against God for unfairly visiting this curse upon

all

womankind to punish

one

woman's sin. How my mother

hated

Eve! If a preacher mentioned her in a sermon, Mother would stand up, slash him with the daggers of her eyes, and stomp out of the church as though she were crushing a detested enemy with every step.

It was not time for the blood when she died. I had no inkling that anything was wrong, and neither, I think, did she. She had just finished braiding my unruly red hair into crooked pigtails tied with sky-blue ribbon at the ends and we were in the kitchen baking gingerbread. She was happy and humming as she bent to pick me up. The cookies were shaped like little men and I was to give them raisins for eyes and red currants for mouths and she was going to make some white icing for us to dress them in. What fun we would have, she said, drawing in bow ties and buttons and stripes and flowers on their suits and vests. She swung me up onto her hip, then suddenly her face went white as the new paint Father had just put on the farmhouse, and she dropped me. . . . She just let go and

dropped me!

dropped me!

I was more surprised than hurt, though I skinned my elbow on the floorboards. I sat up in surprise, rubbing it, whimpering a little when I saw blood, and staring up at her with trembling lips and tears poised to pour. I knew something

must

be wrong. Mother had

never

dropped me before!

must

be wrong. Mother had

never

dropped me before!

She gasped and hunched forward, hunkering down, hugging her lady parts, and I saw the blood seep, like a slow-blooming red rose, through her white apron. She gave a choking, anguished cry and fell to the floor and lay there, her body jerking and spasming while her hands still clutched tight between her legs as though they could somehow stanch the fatal flow. Then she was still. I had never been so afraid. I shook her, and cried, slapped, and shouted at her, but she just lay there, still, silent, and so very white as her blood seeped out and spread slowly across the floor, inching toward me, as if it were a monster reaching out ravenous red fingers, coming to get me, steadily advancing, to grasp the hem of my sky-blue cotton dress and white pinafore. I backed away until my spine bumped the wall and my bottom thudded down onto the floor.

When Emma came home from school she found me crying, howling like Mother used to do, reaching up to her with blood-gloved hands, sitting in the sticky, cooling dark-red pool of our mother's blood. The backside of the ruffled white pantalets I wore beneath my skirt had turned completely red and was glued to my skin. That day my whole world seemed to have been suddenly dyed red. I thought I would never feel clean again.

Serious and grave even in childhood, Emma calmly knelt down in the bloodâI vividly remember the ends of her long black pigtails trailing in the blood, like an artist's sable brush being dipped in crimson paintâand rolled Mother over onto her back to make sure the flame of life had truly gone out. Tenderly, Emma kissed the stone-cold brow and closed the wide staring eyes. Then she took Mother's hand, kissed it, and clasped it to the heart beating fast beneath her flat, childish breast covered by the garish purple, yellow, and magenta plaid silk of the last dress Mother had made for her, and solemnly promised to “always look after Baby Lizzie all the days of my life.” Only then did she release Mother's hand and turn to me. She gathered me up in her arms, promising my clinging, wailing self that she would “

never

let go.”

never

let go.”

It was a promise the child I was then was glad she made but the passage of time would often give me cause to regret. What was comforting to a hysterical three-year-old felt to a woman of thirty like a kraken's

crushing

embrace of the ship or whale it was attacking. Every time I saw paintings or engravings of such scenes I

always

thought of Emma. Once, as a subtly intended hint, when I was well into my teens, I gave her such a painting that I found in a little shop in New Bedford as a birthday present, but Emma never guessed its significance; she just couldn't see that I was the whale and she was the kraken.

crushing

embrace of the ship or whale it was attacking. Every time I saw paintings or engravings of such scenes I

always

thought of Emma. Once, as a subtly intended hint, when I was well into my teens, I gave her such a painting that I found in a little shop in New Bedford as a birthday present, but Emma never guessed its significance; she just couldn't see that I was the whale and she was the kraken.

I tried valiantly to shake the remnants of the dream off, but it kept clinging to me like that red sticky blood. I didn't want to think about Mother or her blood that morning. I was going away. I was excited and didn't want

anything

or

anyone

to spoil it. For the

first

time in my thirty years of life I was about to spread my wings and fly out of Fall River, Massachusetts, and escape into the great big, wide, wonderful world and put an entire ocean between me and the cramped closeness of the place my sister called “the house of hate” because the anger, resentment, and frustration that lived inside it was far stronger than its flimsy drab gray-tinged olive walls, so powerful and palpable it seemed to be the only thing holding our family together. Without that simmering animosity gluing us together, I sometimes thought, we'd fall to pieces and have nothing to say and never give a single thought to one another.

anything

or

anyone

to spoil it. For the

first

time in my thirty years of life I was about to spread my wings and fly out of Fall River, Massachusetts, and escape into the great big, wide, wonderful world and put an entire ocean between me and the cramped closeness of the place my sister called “the house of hate” because the anger, resentment, and frustration that lived inside it was far stronger than its flimsy drab gray-tinged olive walls, so powerful and palpable it seemed to be the only thing holding our family together. Without that simmering animosity gluing us together, I sometimes thought, we'd fall to pieces and have nothing to say and never give a single thought to one another.

I rolled over and curled onto my side, drawing my knees up tight against the cramps, frowning at the faintly metallic tang and disgusting dampness of blood on my light flowered cotton summer nightgown. Always erratic, defying the discreetly penciled notations on my calendar trying to predict its arrival, my despised monthly visitor had come early.

I had bathed late last night, the lamplight giving a soft golden glow to the dark, dank cellar, keeping the dusty boxes of old tools and odds and ends, and the cobwebs in the corners, in the shadows where they belonged, while I sat with my knees drawn up to my breasts, my ample hips and thighs squashed uncomfortably into the old dented tin hipbath, soaking in lukewarm water heated on the kitchen stove and carried down the steep dark stairs in heavy pails by our Irish Maggie before she retired for the night. I had stopped my ears as usual to Father's penurious tirade, exclaiming for what must have been the ten thousandth time that we women should all arrange to bathe upon the same dayânot the night, mind you!âand be quickly in and out of the tub, none of this slothful sitting and soaking, a swift scrubbing with strong lye soapânone of that expensive lavender and rose or lily-of-the-valley nonsense!âthen a rapid rinse and a brisk rubdown with a towel was all that was required. Father would never even think to take a bath any other way, for

his

was the

right

way and his mind was a barred and locked door to the idea that someone else's way might be the right way for them. And we should use the same bathwater, he insisted, to save time and water and cause less trouble to the Maggie. None of us were filthy as coal miners after all. We hardly did anything anyway to raise a sweat or gather grime onto our persons; we were just a lot of lazy females who, between the three of us, could not even keep a decent house and had to waste $4 a weekâthe stupendous sum of $208 a yearâupon a maid. And my stepmother, Abby, was so fat she couldn't fit into the tub at all, and could only stand in it and sluice and scrub as best she could, sometimes using a rag tied to a stick to reach difficult areas, since none of us ungrateful girls were charitable enough to help her, so the water could hardly be considered used at all.

his

was the

right

way and his mind was a barred and locked door to the idea that someone else's way might be the right way for them. And we should use the same bathwater, he insisted, to save time and water and cause less trouble to the Maggie. None of us were filthy as coal miners after all. We hardly did anything anyway to raise a sweat or gather grime onto our persons; we were just a lot of lazy females who, between the three of us, could not even keep a decent house and had to waste $4 a weekâthe stupendous sum of $208 a yearâupon a maid. And my stepmother, Abby, was so fat she couldn't fit into the tub at all, and could only stand in it and sluice and scrub as best she could, sometimes using a rag tied to a stick to reach difficult areas, since none of us ungrateful girls were charitable enough to help her, so the water could hardly be considered used at all.

The bar of lavender soap that I had stealthily slipped into my purse while I was perusing the wares on display at Sargent's Dry Goods one day, was the only luxurious thing about me as I sat there shivering and hugging my knees, dreaming of a proper, modern bathroom with a big porcelain tub I could stretch out in, like a reclining mermaid, basking in water that ran hot or cold at the mere twist of a nickel-plated knob, and a

real

toilet, instead of a crude hole covered by a wooden box seat, standing regal as a porcelain throne, shining like a pearl, on a floor of gleaming tile instead of hard-packed earth, with proper paper to wipe with instead of a stack of old magazines to rip pages from as the need required. I remember I used to sit there while voiding my bowels and in the dim lamplight gaze yearningly upon the fashion plates depicting the latest styles from Paris, and pictures of beautiful ladies enjoying a life of luxury and ease, of dining and dancing, opening nights at the opera and plays, boating excursions, sleighing parties, oyster suppers, clambakes, and games of tennis and croquet with their beaus, and imagine I was one of themâthe belle of the ball in strawberry-pink taffeta dancing till dawn in the arms of a prince! Or a grand lady in pink satin, pearls, and point lace surrounded by adoring gallants serving her dainty cakes with pastel-colored frosting upon a silver tray. When the time came to wipe, I would always seek a page of print instead of soiling the images that inspired my dreams, though the others in the house were not quite as discriminating.

real

toilet, instead of a crude hole covered by a wooden box seat, standing regal as a porcelain throne, shining like a pearl, on a floor of gleaming tile instead of hard-packed earth, with proper paper to wipe with instead of a stack of old magazines to rip pages from as the need required. I remember I used to sit there while voiding my bowels and in the dim lamplight gaze yearningly upon the fashion plates depicting the latest styles from Paris, and pictures of beautiful ladies enjoying a life of luxury and ease, of dining and dancing, opening nights at the opera and plays, boating excursions, sleighing parties, oyster suppers, clambakes, and games of tennis and croquet with their beaus, and imagine I was one of themâthe belle of the ball in strawberry-pink taffeta dancing till dawn in the arms of a prince! Or a grand lady in pink satin, pearls, and point lace surrounded by adoring gallants serving her dainty cakes with pastel-colored frosting upon a silver tray. When the time came to wipe, I would always seek a page of print instead of soiling the images that inspired my dreams, though the others in the house were not quite as discriminating.

Other books

Love Delayed by Love Belvin

Stormy Challenge by Jayne Ann Krentz, Stephanie James

The Low Sodium Cookbook by Shasta Press

Confessions of a Scoundrel by Karen Hawkins

Loose by Coo Sweet

No Longer at Ease by Chinua Achebe

Dirty Rotten Tendrils by Collins, Kate

At Fault by Kate Chopin

Pour Your Heart Into It by Howard Schultz

Romancing the West by Beth Ciotta