The Setting Sun (33 page)

Authors: Bart Moore-Gilbert

Kanishka’s party is a soothing distraction to round off a tumultuous day. Briha drops me at the hotel to change and while waiting for him to return, I buy a bag of bright-dyed candies for his boy from the shop next door. The flat’s in a modern three-storey block, ten minutes away on the back of Briha’s Honda. There are already quite a few people, though I’m disconcerted to find all the men are in the front room and the women in the kitchen. Class appears to make no difference to the gender segregation I’ve encountered throughout my trip. Briha takes me through to meet his wife, a very shy, pretty woman who hands me a plate of dal, rice and vegetable

curry, with an iced bun and a piece of cake wedged incongruously either side. My host then proudly points out the recently completed terrace off the kitchen, where one or two men are smoking, before leading me back to the living room. In one corner a video plays. His wedding, Briha explains. But their little boy holds centre stage today, seated against a bolster, dressed like a miniature maharajah, surrounded by friends. He wails when he catches sight of me.

‘It’s your colour,’ Briha chuckles, ‘he’s not used.’

While his mother comforts the boy, Briha insists on tying a long-tailed cinnamon-coloured Kolhapur turban on my head and everyone applauds and wants photographs. I’m sure it looks ludicrous with cut-offs and sandals. Then the blessing takes place. Trays of food are circled round Kanishka’s head, and he’s offered spoonfuls while guests throw rice over him. Self-possession restored, the boy’s as gracious as a little prince. Then everyone sings ‘Happy Birthday’, followed – to the same tune – by ‘May God Bless You’, before Briha cuts a cake, garishly decorated with miniature funfair fixtures made of icing. It’s heartening. In modern India, some dalits, at least, are entering the middle classes. Things have moved on from their predicament under the Raj, described so poignantly in Anand’s

Untouchable

or Nayakwadi’s story about his helper’s grandfather.

Later, I chat with a couple of Briha’s colleagues who were at yesterday’s debate on terrorism, some civil servants and IT types. One approaches with hands full of sodas, inviting me to help myself.

‘Many Marathis in London,

yaar

?’ he grins.

‘Don’t know I’ve ever met one. Plenty of Gujaratis and Sikhs and Tamils.’

‘Those types are everywhere. Especially here in Maharashtra,’ he adds in an aggrieved tone. ‘Traders. We Marathis are soldiers and artists and administrators. Gujaratis and Sikhs, they will always cheat you. As for Tamils …’ I’m afraid he’s

going to spit. ‘Never trust one. They will eat the food off your table in the evening and stab you in the back the following morning.’

Remembering ASP Shinde’s comments in Satara police station about the problem of local chauvinism towards those from other parts of India, I escape to the terrace. It’s shaded by a gigantic jackfruit tree, stars blinking through its leaves. I lean against a concrete pillar and gaze at them, thinking about Nayakwadi’s closing remarks. Did Bill ever acknowledge his mistakes or feel remorse about the past?

At his father’s call, the boy makes his way down from the roof of the four-storey block of flats where they’re living in Dar es Salaam. It looks onto Selandar Bridge, which divides the older part of the city from Msasani Peninsula and Oyster Bay, where the new African ministers and diplomats live. The boy never wanted to live in a city, but he’s enjoying it now. From here it’s an easy walk either to the beach or the Italian ice-cream parlour and bookshop off Independence Avenue. And the flat roof’s the perfect place to practise football on his own, when he can’t bribe Lindsay to play in goal, the parapet walls perfect for angled passes and thunderous shots. His father’s promised a kick-around after the fancy-dress party at the Gymkhana Club

.

The boy’s got his Shaka, King of the Zulus, outfit ready in his bag, with lion-claw necklace and zebra-skin armband, though he’s had to make do with a Maasai spear, stabbing sword and short shield. Since discovering

King Solomon’s Mines,

he’s become obsessed by all things Zulu. Everyone else is going in some kind of British army uniform, Marine Commandos, Guards, SAS. The boy’s worried about his raffia skirt. Will everyone laugh?

‘Look, old chap, Shaka didn’t racket round in a jockstrap or shorts,’ his father reassured him that morning. ‘Let them have a taste of your

assegai

if anyone gives you gyp.’

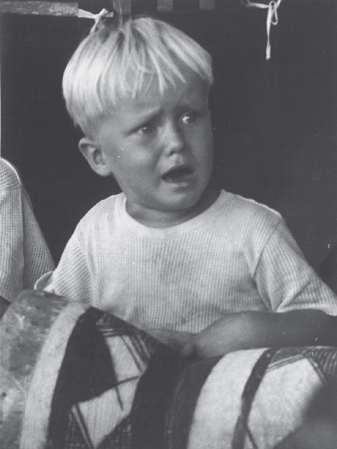

The author preparing for a fancy-dress party c. 1958

He’s already on the stairs as the boy reaches the landing, juggling a tennis ball in one hand

.

‘Come on, I’ve got your stuff. Want some water?’ He offers the Gordon’s Gin bottle, sweating with condensation from the fridge

.

When he’s finished drinking, the boy leaps down the stairs, two and three at a time. ‘Race you.’

‘Hey, that’s not fair, I’m carrying everything.’

The boy goes back up, but his father shoos him away with a laugh

.

‘Careful on the second floor.’

The tiling’s being relaid and there’s only rough cement for the moment. He’s already tripped once and grazed his elbow

.

Placing the boy’s holdall and his sports bags on the seat behind, his father settles behind the wheel

.

‘Did you remember Neil’s goggles?’ the boy asks. ‘The Jenkins are going snorkelling off South Beach tomorrow.’

There’s an impatient sigh. ‘We’re late.’

‘I promised, dad.’

‘Well,’ his father replies, singling out the right key on his fob, ‘run back up, there’s a good chap.’

The boy leaps back up the stairs almost as quickly as he descended. He loves the way his golden body feels. He never seems to tire, however hot it gets, however long he plays football. He wants to play for the Gymkhana Club when he’s older, like his father. Perhaps in a few years they’ll turn out together. Goalkeepers last longer than outfield players, he knows that, and his father’s still fit as a flea

.

He opens the door to the flat quietly as he can. His mother takes a nap in the late afternoon. So it’s a surprise to find her in the kitchen. To his horror, she’s crying, misery scored in a deep line between her eyebrows. The boy freezes. She says nothing as she turns, tears running silently down her face

.

‘Mummy, what is it? What’s the matter?’

She steps forward quickly and hugs him. It’s not something she often does, so the boy knows this must be serious. Behind his back he can hear her sniffling into the paper tissue she always carries. Despite himself, he hates the way she does that. Why can’t she use a proper handkerchief like other mothers?

‘It’s nothing. What did you come back for?’

‘Daddy forgot Neil’s goggles.’

‘Better get them then.’

Unsure what to do, the boy finally breaks away and darts into the bathroom. By the time he returns, his mother’s wiping her eyes

.

‘You sure you’re OK, mummy?’

‘Yes,’ she sighs, to his guilty relief, ‘run along now or you’ll miss the party. I stitched up the raffia skirt for you.’

‘Alright, old chap?’ his father says as his son slams the passenger door of the Land Rover

.

The boy stares straight ahead. ‘Mummy’s crying,’ he eventually mutters. Will his father cancel the outing now?

‘What?’

His son nods

.

‘Stay here.’

His father’s gone more than half an hour. The boy tries to understand what’s going on. He’s hardly ever seen his mother cry. Last time was several years back, when he nearly dashed his brains out with a stone-hammer which bounced up like a rubber ball from the rock half-buried in the drive in Manyoni. He’d been helping the masons build the new veranda. The blow stunned him for several minutes and removed a perfect square inch of skin above his eyebrow. Like the mark below his left knee, where he fell from a tree, he’s now proud of the scar

.

What can it be? Ever since he saw his father kissing Viva Balson, the boy’s kept a wary eye out. But that was ages ago. The boy still sees Eric and Viva when they drop off or collect their kids from school. But so far as he knows, his father hasn’t seen the Balsons since they left the Ngorongoro Crater

.

Eventually, his father returns, looking thoughtful. When he gets into the driver’s seat, he doesn’t say anything for a while. Then he turns to the boy as if suddenly remembering he’s there

.

‘What is it, dad?’

To his alarm, his father leans forward to rest his forehead on the steering wheel. For a moment, his shoulders heave. The boy repeats the question. When no answer comes, he slides across the seat and puts a hand on his father’s arm. There’s another shudder before his father looks up again

.

‘Have to try harder,’ he whispers

.

‘What do you mean?’

‘It’s difficult for mummy now. Ames has gone to school in England. I’m at the office all day, and you and Lindsay are away at St Michael’s most of the time. And no Kimwaga to help.’

There isn’t room in the flat. It’s the only black mark against Dar es Salaam, that and the fact they can’t keep dogs. Tunney and Dempsey have stayed behind in Tabora until his father knows how long they’ll be in Dar es Salaam. The Emperor Haile Selassie has offered his father a five-year contract to open the first national parks in Ethiopia and everything’s up in the air

.

‘That woman who comes is useless. Mummy has to do it all again herself. She spends too much time on her own.’

‘Why doesn’t she come to the Club?’

‘She doesn’t want to.’

‘Should we try to help more?’

His father smiles gratefully

.

He says nothing as they drive into town. At the entrance to the Gymkhana Club the boy sees his friends milling around, inspecting each other’s uniforms. His father suddenly turns to him

.

‘Look, old chap, I’ll just drop you at the party if you don’t mind. I’m going to head home now. We’ll have a kick-around another time.’

‘Shall I come back, too?’

‘No, everyone’s waiting for you. I’ll pick you up later.’

A hand powerful as a bear’s squeezes the boy’s for a moment before reaching back for the bag containing the fancy-dress outfit

.

‘Bayete, Nkozi,’

he salutes as the boy turns back on the veranda of the Club

.

CHAPTER 13

Like Father, Like Son

‘Poel will be here in the next couple of days,’ Rajeev affirms, during his early morning catch-up call. ‘He’ll see what he can do, once he’s back in the office. You’ve time to visit Ratnagiri, then. Nice place, like Goa fifty years ago. I think you deserve a little break, no? Gather your strength before Mumbai?’

It makes sense. A chance to see another of Bill’s postings, the last before he left India. There simply isn’t time to get up to Nasik or Ahmedabad this trip. And since I’ve missed Bhosle, it’s unlikely I’ll be able to clarify whether Bill was ever in Sindh.

There’s no ‘Volvo’ from Kolhapur, so it’s the local country bus, hot and sticky, people packed in the aisle and a strong whiff of poultry from the coop cradled by the woman across from me. To begin with, I’m diverted by my neighbour, an eighty-year-old veteran of the Mahratta Light Infantry. He’s on a pilgrimage to the great temple at Ganpatipule, north of Ratnagiri – preparation, as he puts it, ‘for going upstairs’. His mischievous tales about the mishaps of military life have me in stitches. Until, that is, the bus begins its descent to the Konkan littoral; with steepling crags and plunging ravines to either side, the constant squeal of brakes prevents conversation. We lurch against each other as the driver spins his wheel like a ship’s captain, one way then the other, to the vehement klaxons of lorries coming the other way and the clucks of scrabbling chickens. The veteran places a finger in each ear and closes his eyes with an anxious expression, as if we’re headed ‘upstairs’ sooner than planned.

Finally we reach the safety of the coastal plain, where it’s much sultrier, air hazy and saline as we approach the ocean. The landscape’s also very different from up on the Deccan plateau, orchards of cashew and areca palm, mango, banana and endless emerald paddy fields. On this final leg we’re shown a video, perhaps as a reward for our fortitude. It’s an irritatingly enjoyable Bollywood musical in which an over-loud song with the punchline ‘I’ve got your number’ is endlessly repeated by actors seemingly trained at the Benny Hill Academy of Innuendo. The attendant squeezes jovially through the press in the aisle, offering an acidic cologne which my neighbour slaps gratefully on his hands and neck, as if purifying himself for his pilgrimage. Will this next stage of my own quest provide further enlightenment? And will there be expiation? After Chafal and the nationalist leaders, I sense my trip may be beginning to wind down. If only I can get to hear Bill’s own voice before I leave India. Everything depends on Poel, unless by some miracle some of his confidential weeklies have been preserved in Ratnagiri.