The Sexual History of London (5 page)

Read The Sexual History of London Online

Authors: Catharine Arnold

Compared with French brothels and houses of ill fame elsewhere in the capital, the Bankside stews were dull, functional places. No entertainments were permitted, and it was forbidden to serve any âbreed, ale, flesh or fyssh' while âcoles, wod or candel nor anie othere vitaill [necessity]' were banned.

20

Even the reference to the client staying all night had a practical function, to cut down on promiscuity and contain disease.

According to Stow's

Survey of London

, there were originally about eighteen of these brothels. The exteriors were painted white, so that they were clearly visible across the river, and they had similar names to taverns: Ye Boar's Hedde; The Castle; The Cross Keyes; The Cardinal's Cap (accompanied by a suggestive illustration of a scarlet skullcap reminiscent of a foreskin) and, rather more poetically, The Half Moon; The Unicorn and The Blue Maid.

21

That these institutions appeared similar to taverns was entirely intentional. Many places of entertainment operated in the shadowy half-world where legitimate inns also doubled as brothels, and many of the girls who worked in the taverns seized the opportunity for extra remuneration by entertaining their patrons. There was also plenty of scope for enterprising amateurs, married women who, feeling neglected by their husbands, repaired to âhouses of assignation' where they could satisfy their own appetites with willing paramours or turn a coin with a wealthy client looking for an upmarket girl.

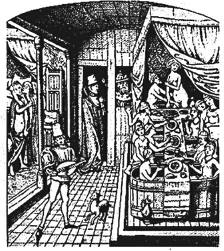

While the taverns provided entertainment in the form of food and drink, the whorehouses effectively solved the problem of where to billet the large numbers of unattached men descending on London in search of work; they were the perfect municipal solution to overcrowding. One contemporary engraving of a medieval brothel shows us the kind of welcome a young man could expect: a handsome young noble is being attended by two young whores, watched by his jester, who looks horrified by the proceedings while slyly peeping through his fingers. The bed looks rather hard, but there are adequate refreshments. The girls appear somewhat coy, but the second is draped in a banner encouraging enticement to sin, designed to overcome the power of the cross worn around the young nobleman's neck, while the first girl is administering manual stimulation.

22

These brothels also supplied the âdaughters of the city' or civic whores who were rolled out to greet distinguished visitors, draped in suitably diaphanous raiment, although there is no evidence that the City of London followed the continental practice of actually hiring the whores for their guests.

Despite all attempts by the authorities to restrict the sex trade to Bankside, prostitution inevitably flourished in other areas of London, spreading gradually to encompass West Smithfield, particularly Cock's Lane, outside Newgate. Records have revealed a maze of alleys in Moorgate and Cripplegate (near our contemporary Coleman Street and Guildhall) full of brothels. There was no mystery as to the trade that was conducted in these small streets, as one name indicates. The first mention of it appears in 1276, when a property belonging to Henri de Edelmonton was apparently located in the memorable thoroughfare of Gropecunt Lane.

23

The Anglo-Saxon name indicates the most abject, desperate form of prostitution, with clapped-out, prematurely aged prostitutes catering for a desperate clientele who were charged a tiny sum in exchange for the opportunity to put their hands up their skirts.

Maiden Lane was nearby, along with Love Lane, full of âwanton maidens' according to the historian John Stow.

24

Gropecunt Lanes were not restricted to England. In Paris, the Rue Trousse Puteyne literally meant âthe slut's slit'. Back in England, Gropecunt Lane eventually became the more respectable âGrape Street' and eventually âGrub Street', the home of the literary hack (reminding all those who live by the pen that there is more than one way to prostitute oneself). Codpiece Lane became Coppice Lane, but there was nothing that could be done about Sluts' Hole, which was transformed into Sluts' Well before disappearing for ever into the Tenter Ground in 1700.

25

The stews also represented another development in London's sex trade: the return of the bath house. Bathing and washing had not been popular pursuits in early medieval London. Indeed, the Danish invasion back in 870

AD

must have come as a relief for many women, amateur and professional, since Danish soldiers, unlike the Saxons, were famous for their good looks and high standards of personal hygiene. According to the medieval historian John of Wallingford (died 1214), the Danes represented a serious threat to jealous husbands and local lads. Not only did they comb their hair every day and take a bath on Saturdays, but they changed their clothes regularly. It was scarcely surprising that they were particularly successful in seducing married women, and even persuading the daughters of the nobility to become their concubines.

26

Most Londoners of the period were careless of personal hygiene and did not regard cleanliness as being next to godliness. In some cases, indeed, the reverse was true. Consider this account of Thomas à Becket, murdered on the orders of Henry II in Canterbury Cathedral in December 1170. When his faithful acolytes went to recover the body, they peeled off layer after layer of garments to reveal a stinking hair shirt, hopping with fleas. Dirt and squalor ruled supreme. King John took a bath every three weeks and King Henry III would bravely ârepair to the wardrobe at Westminster where he was wont to wash his head', a decidedly hazardous procedure.

On rare occasions, for those higher up the social scale, wooden tubs were used as baths. In the summer months, some Londoners would bathe in the Thames, but this was scarcely a practice which could be adopted all year round. There were few lavatories, as such: brimming chamber-pots were emptied into the street and the contents carried off down the gutters into the nearest river or stream. In 1306 Ebbgate Street, near the river, just south of Thames Street, was choked with shit

quarum putredo cadit super capitas hominum transeuntium â

falling on the heads of passers-by.

27

There were public latrines, or ânecessary houses', over running streams, with the human by-products then passing into the water supply and hence into the food chain. A cleansing team dispatched to Newgate gaol in 1283 consisted of

thirteen

workmen and took five days to clean the latrine, or

cloacum.

They were well recompensed for their labours though, receiving 6d a day, three times more than unskilled workers at the time. Particularly noisome streets were referred to as Pissing Lane, Stynkyng Alley or even Shiteburnlane.

But public bathing became fashionable once more when returning Crusaders brought with them their taste for the Turkish bath, or âhammam'. Public bath houses opened in France, Germany and eventually London. The enterprising owner would blow a horn to announce opening time, and locals would strip and walk to the bath house, stark naked during the summer months. Soon a taste for optional extras developed, and, just as in Roman London, âthe stews' became synonymous with brothels. Cleanliness also became desirable to the sex worker (and her client). Although few remedies were known, there was a recognition that venereal disease flourished in insanitary conditions, and being able to offer a clean whore and washing facilities were incentives.

The attitude of the authorities towards prostitution and licentious behaviour in London fluctuated according to who was in power. Despite the fact that the Church and the crown derived a considerable income from prostitution, their stance vacillated between tolerance and strict punishment according to the personal views of the reigning monarch. For instance, Richard I took a decidedly liberal view of prostitution, no doubt because he had great recourse to brothels himself, to such an extent that he was actually arrested in a brothel in Paris. When Richard's brother, King John, succeeded him in 1199, he took no action against the stews. John's son, King Henry III, grew up to be one of the most avaricious and close-fisted monarchs in history, notorious for his high taxes, but for some unaccountable reason the brothels escaped his attention.

A medieval âstew' or bath house. Note that hospitality extended to dining facilities in the tub.

But the mood changed significantly when Edward I came to power in 1272. A moral crusader (as well as a king levying taxes to pay for his part in the Crusades), Edward set about a clean-up campaign. In 1285 he ruled that âno courtesans nor common brothel keepers shall reside within the walls of the City, under pain of imprisonment'.

28

Edward's rationale was that the presence of prostitutes or âwomen of evil life' attracted criminals and murderers, and that any common prostitute found within the city walls was to be imprisoned for forty days and reminded of the fact that she belonged beyond the city limits, in Southwark. As well as taking a firm line on prostitution, Edward I drove out the remaining Jews who had not already left England after the massacre unintentionally initiated by Richard I when he banned the Jews from his coronation on the grounds that he was a âCrusader'. This thoughtless gesture led to anti-Semitic riots, although Richard later punished the protagonists. Despite the fact that the royal family had relied on the Jews for their financial and medical acumen, they had long suffered exclusion and persecution. The Jews, and the âTurks' or Muslims, were even excluded from visiting brothels. In 1290, Edward stated that: âthose who have dealings with Jews and Jewesses and those who commit bestiality and sodomy are to be burned alive after legal proof that they were taken in the act and publicly convicted'.

29

This was especially hypocritical on Edward's part, as subsequent records reveal that, not only did the king derive an income from the stews of Southwark, but he had also issued a licence to run a brothel to Isaac of Southwark, one of the richest Jews in England.

30

The pleasure-loving Edward II was content to let the brothels flourish, although his own tastes ran to boys. He was murdered, horribly, at Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire, when a red-hot poker was rammed up his anus until it reached the intestines â a ghastly âpunishment' for weak governance and for his homosexuality. Edward's greatest achievement was to found the Lock Hospital in Southwark in 1321. Originally intended for lepers (âlocks' refers to the âlocks', or rags, that patients used to cover their lesions), it took on a new role centuries later in 1747, as the Lock Hospital on Hyde Park Corner, specializing in venereal disease, and generations of afflicted Londoners had cause to be grateful to its founder.

31

When Edward's son, Edward III, succeeded in 1327, he took an enlightened attitude to the brothels. In 1345 he reviewed the legislation of 1161 on the stews of Southwark recommending that the prostitutes wore a distinguishing mark in the form of a red rosette. A similar system operated in Avignon, France, while in Switzerland harlots wore a little red cap. Unfortunately, when it came to lewd and immoral behaviour, one law operated for the rich and another for the poor. Edward III's Plantagenet court was characterized by immorality, with the royalty and aristocracy free to indulge their sexual proclivities to the full. There was even a brief fashion for female âtopless jousting' with scantily clad young women appearing at tournaments âdressed in a lascivious, scurrilous and lubricious fashion, with their breasts and bellies exposed',

32

according to one contemporary writer, while another described âladies wearing foxtails sewed withinne to hide their arse'.

33

While such frolics were tolerated with amusement in court circles, immorality lower down the social scale was dealt with more harshly. As one contemporary nobleman expressed it, âthose that were rich were hangid by the purse, and those that were poor were hangid by the necke!'

34

The street whores, or ânightwalkers', received the most draconian penalties, such as the âcucking' and âducking' stools.

A âcucking stool' sounds inoffensive enough, but its origins are truly disgusting. According to Tacitus, in Germany, cowards, sluggards, debauchees and prostitutes were suffocated in mires and bogs by this method, along with âpests' and useless members of society.

35

âCucking' derives from the old Icelandic â

kuka

'; like the Latin â

caca

' it means shit. Although it sounds like a joke to us now it was anything but. The unfortunate victim was fastened into a chair outside his or her own house and then wheeled to the location, where the chair was attached to a fulcrum and suspended over a deep pit of excrement into which they were lowered and where they would choke to death. The tradition lasted into Norman times, when it was used as a punishment for bakers and brewers who adulterated their products, and for âbawds' (madams) and âscalds', noisy and aggressive women who fought in the street.