The Short Reign of Pippin IV (5 page)

Read The Short Reign of Pippin IV Online

Authors: John Steinbeck

Works Consulted

Astro, Richard.

John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: The Shaping of a Novelist

. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1973.

John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: The Shaping of a Novelist

. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1973.

Benson, Jackson J.

The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer

. New York: Viking, 1984.

The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer

. New York: Viking, 1984.

Brown, Dan.

The Da Vinci Code

. New York: Doubleday, 2003.

The Da Vinci Code

. New York: Doubleday, 2003.

Coers, Donald V., Paul D. Ruffin, and Robert J. DeMott, eds.

After

The Grapes of Wrath:

Essays on John Steinbeck in Honor of Tetsumaro Hayashi

. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1995.

After

The Grapes of Wrath:

Essays on John Steinbeck in Honor of Tetsumaro Hayashi

. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1995.

Ditsky, John. “âSome Sense of Mission': Steinbeck's

The Short Reign of Pippin IV

Reconsidered.”

Steinbeck Quarterly

16 (1983), 79-89.

The Short Reign of Pippin IV

Reconsidered.”

Steinbeck Quarterly

16 (1983), 79-89.

Fensch, Thomas.

Steinbeck and Covici: The Story of a Friendship

. Middlebury, Vermont: Paul S. Eriksson, 1979.

Steinbeck and Covici: The Story of a Friendship

. Middlebury, Vermont: Paul S. Eriksson, 1979.

Fontenrose, Joseph.

John Steinbeck: An Introduction and Interpretation

. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963.

John Steinbeck: An Introduction and Interpretation

. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963.

French, Warren.

John Steinbeck,

2nd ed. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1975.

John Steinbeck,

2nd ed. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1975.

Gildea, Robert.

France Since 1945

. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

France Since 1945

. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Lisca, Peter.

The Wide World of John Steinbeck

. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1958.

The Wide World of John Steinbeck

. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1958.

McMillan, James F.

Dreyfus to de Gaulle: Politics and Society in France 1898-1969

. London: Edward Arnold, 1985.

Dreyfus to de Gaulle: Politics and Society in France 1898-1969

. London: Edward Arnold, 1985.

McMillan, James, ed.

Modern France 1880-2002.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Modern France 1880-2002.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Owens, Louis. “Steinbeck's âDeep Dissembler':

The Short Reign of Pippin IV,” The Short Novels of John Steinbeck,

ed. Jackson J. Benson. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1990.

The Short Reign of Pippin IV,” The Short Novels of John Steinbeck,

ed. Jackson J. Benson. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1990.

Parini, Jay.

John Steinbeck, A Biography.

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995.

John Steinbeck, A Biography.

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995.

Park, Julian, ed.

The Culture of France in Our Time.

Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1954.

The Culture of France in Our Time.

Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1954.

Rucklin, Christine. “Beyond France: Steinbeck's

The Short Reign of Pippin IV

.” In

Beyond Boundaries: Rereading John Steinbeck,

ed. Susan Shillinglaw and Kevin Hearle.

The Short Reign of Pippin IV

.” In

Beyond Boundaries: Rereading John Steinbeck,

ed. Susan Shillinglaw and Kevin Hearle.

Serfaty, Simon.

France, De Gaulle, and Europe: The Policy of the Fourth and Fifth Republics Toward the Continent.

Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1968.

France, De Gaulle, and Europe: The Policy of the Fourth and Fifth Republics Toward the Continent.

Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1968.

Singer, Barnett.

Modern France: Mind, Politics, Society.

Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1980.

Modern France: Mind, Politics, Society.

Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1980.

Steinbeck, Elaine and Robert Wallsten, eds.

Steinbeck, A Life in Letters.

New York: Viking, 1975.

Steinbeck, A Life in Letters.

New York: Viking, 1975.

Steinbeck, John. “The Soul and Guts of France.”

Colliers

30 (August 30, 1952), 26-28, 30.

Colliers

30 (August 30, 1952), 26-28, 30.

Watt, F. W.

John Steinbeck

. New York: Grove Press, 1962.

John Steinbeck

. New York: Grove Press, 1962.

Williams, Philip M.

Wars, Plots and Scandals in Post-War France.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970.

Wars, Plots and Scandals in Post-War France.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970.

Number One Avenue de Marigny in Paris is a large, square house of dark and venerable appearance. The mansion is on the corner where de Marigny crosses the Avenue Gabriel, a short block from the Champs Elysées and across the street from the Elysée Palace, which is the home of the president of France. Number One abuts on a glass-roofed courtyard, on the other side of which is a tall and narrow building, once the stables and coachmen's quarters. On the ground level are still the stables, very elegant with carved marble mangers and water troughs, but upstairs there are three pleasant floors, a small but pleasant house in the center of Paris. On the second floor large glass doors open on the unglassed portion of the courtyard which connects the two buildings.

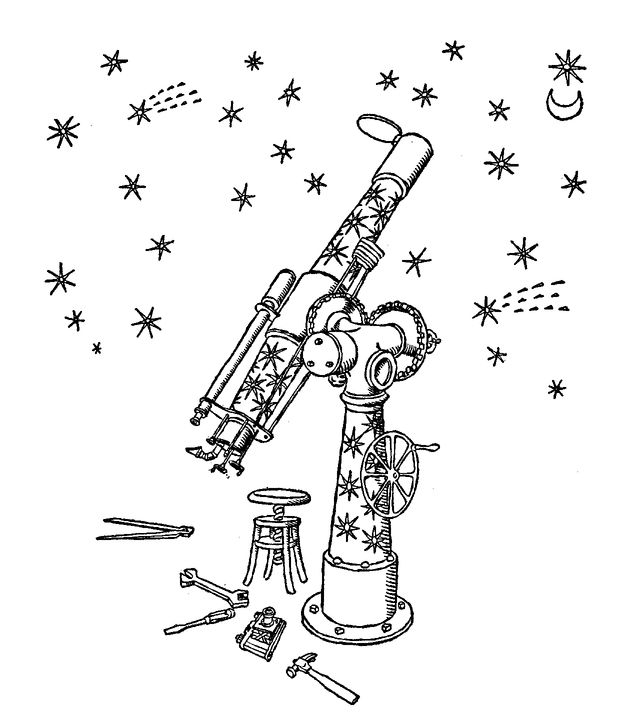

It is said that Number One, together with its coach house, was built as the Paris headquarters of the Knights of St. John, but it is presently owned and occupied by a noble French family who for a number of years have leased the converted coach house, the use of the courtyard, and half of the flat connecting roof to M. Pippin Arnulf Héristal and his family, consisting of his wife, Marie, and his daughter, Clotilde. Soon after leasing the stable house, M. Héristal called on his noble landlord and requested permission to set up the base and mount for an eight-inch refracting telescope on the portion of the flat roof to which he had access. This request was granted, and thereafter, since M. Héristal was prompt with the rent, intercourse between the two families was limited to formal greetings when they happened to meet in the courtyard, which was of course guarded by heavy iron bars on the street side. Héristal and landlord shared a concierge, a brooding provincial, who after years of living in Paris still refused to believe in it. And there were never any complaints from the noble landlord, since M. Héristal's celestial hobby was carried on at night and silently. The passions of astronomy, however, are no less profound because they are not noisy.

The Héristal income was almost perfect of its kind for a Frenchman. It derived from certain eastward-facing slopes near Auxerre, on the Loire, on which the vines sucked the benevolence from the early sun and avoided the poisons of the afternoon, and this, together with a fortunate soil and a cave of perfect temperature, produced a white wine tasting like the odor of spring wildflowersâa wine which, while it did not travel well, had no need, for its devotees made pilgrimage to it. This estate, while small, was perhaps the very best of a holding once very great. Furthermore, it was cultivated and nurtured by tenants expert to the point of magic, who moreover paid their rent regularly and had, generation by generation. M. Héristal's income was far from great, but it was constant and it permitted him to live comfortably in the coach house of Number One Avenue de Marigny; to attend carefully selected plays, concerts, and ballet; to belong to a good social club and three learned societies; to purchase books as he needed them; and to peer as a respected amateur at the incredible heavens over the Eighth Arrondissement of Paris.

Indeed, if Pippin Héristal could have chosen the life he would most like to live, he would have spoken, with very few changes, for the life he was living in February of 19â. He was fifty-four, lean, handsome, and healthy in so far as he knew. By that I mean his health was so good that he was not aware he had it.

His wife, Marie, was a good wife and a good manager who knew her province and stayed in it. She was buxom and pleasant and under other circumstances might have taken her place at the bar of a very good small restaurant. Like most Frenchwomen of her class, she hated waste and heretics, considering the latter a waste of good heavenly material. She admired her husband without trying to understand him and had a degree of friendship with him which is not found in those marriages where passionate love sets torch to peace of mind. Her duty as she saw it was to keep a good, clean, economical house for her husband and her daughter, to do what she could about her liver, and to maintain the spiritual payments on her escrowed property in Heaven. These activities took up all her time. Her emotional overflow was absorbed by an occasional fight with the cook, Rose, and her steady warfare with wine-merchant and grocer, who were cheats and pigs, and, at certain times of the year, ancient camels. Madame's closest friend and perhaps only confidante was Sister Hyacinthe, of whom there will be more later.

M. Héristal was French of the French and yet French plus. For instance, he did not believe it was a sin not to speak French and an affectation for a Frenchman to learn other languages. He knew German, Italian, and English. He had a scholarly interest in progressive jazz, and he loved the cartoons in

Punch

. He admired the English for their intensity and their passion for roses, horses, and some kinds of conduct.

Punch

. He admired the English for their intensity and their passion for roses, horses, and some kinds of conduct.

“An Englishman is a bomb,” he would say, “but a bomb with a hidden fuse.” He also observed, “Almost any generality one makes about the English turns out at some time to be untrue.” And he would continue, “How different from the Americans they are!”

He knew and liked Cole Porter, Ludwig Bemelmans, and, until a few years before, had known sixty per cent of the Harmonica Rascals. He had once shaken hands with Louis Arm-strong and addressed him as Cher Maître Satchmo, to which the master replied, “You frogs ape me.”

The Héristal household was comfortable without being extravagant, and carefully keyed to the family income, which was sufficient for the pleasant but frugal life which, as good French, Pippin and Madame preferred to live. Monsieur's main extravagance lay in the instruments of astronomy. His telescope of more than amateur power was equipped with mounting of sufficient weight and stability to overcome oscillation, and mechanism to compensate for the earth's turning. Some of Pippin's celestial photographs have appeared in the magazine

Match,

and properly so, for he is given credit for discovering the comet of 1951, designated the Elysée Comet. A Japanese amateur in California, Walter Haschi, made a simultaneous report and shared credit for the discovery. Haschi and Héristal still corresponded regularly and compared photographs and techniques.

Match,

and properly so, for he is given credit for discovering the comet of 1951, designated the Elysée Comet. A Japanese amateur in California, Walter Haschi, made a simultaneous report and shared credit for the discovery. Haschi and Héristal still corresponded regularly and compared photographs and techniques.

Under ordinary circumstances Pippin read four daily papers like any good and alert citizen. He was not political except in so far as he distrusted all governments, particularly the one in power, but this too might be said to be more French than individual.

The family Héristal was blessed with only one childâClotilde, twenty years old, intense, violent, pretty, and overweight. Her background was interesting. At an early age she had revolted against everything she could think of. At fourteen, Clotilde determined to be a doctor of medicine; at fifteen she wrote a novel entitled

Adieu Ma Vie,

which sold widely and was made into a motion picture. As a result of her literacy and cinemagraphic success she toured America and returned to France wearing blue jeans, saddle oxfords, and a man's shirt, a style which instantly caught on with millions of gamines who for several years were known as “Les Jeannes Bleues” and caused untold pain to their parents. It was said that Les Jeannes Bleues were, if anything, sloppier and more frowzy than the Existentialists, while their stern-faced gyrations in le jitterbug caused many a French father to clench agonized fists over his head.

Adieu Ma Vie,

which sold widely and was made into a motion picture. As a result of her literacy and cinemagraphic success she toured America and returned to France wearing blue jeans, saddle oxfords, and a man's shirt, a style which instantly caught on with millions of gamines who for several years were known as “Les Jeannes Bleues” and caused untold pain to their parents. It was said that Les Jeannes Bleues were, if anything, sloppier and more frowzy than the Existentialists, while their stern-faced gyrations in le jitterbug caused many a French father to clench agonized fists over his head.

From the arts, Clotilde went directly into politics. At sixteen and a half she joined the Communists and held the all-time record of sixty-two hours of picketing the Citroën plant. It was during this association with the lower classes that Clotilde met Père Méchant, the little Pastor of the Pediment, who so impressed her that she seriously considered taking the veil in an order of nuns dedicated to silence, black bread, and pedicures for the poor. St. Hannah, patron saint of feet, founded the order.

Â

Â

On February 14, a celestial accident occurred which had a sharp effect on the Héristal household. A pre-equinoctial meteor shower put in an untimely and unpredicted appearance. Pippin worked frantically with the blazing heavens, exposing film after film, but even before he retired to his darkroom in the wine cellar off the stable he knew that his camera was not adequate to stop the fiery missiles in their flight. The developed film verified his fear. Cursing gently, he walked to a great optical supply house, conferred with the management, telephoned several learned friends. Then he strolled reluctantly back to Number One Avenue de Marigny, and so preoccupied was he that he did not notice the Gardes Républicains in shining cuirasses and red-plumed helmets, milling their horses around the gates of the Elysée Palace.

Madame was concluding an argument with Rose, the cook, as Pippin climbed the stairs. She emerged from the kitchen, victorious and a little red in the face, while the sullen muttering of the defeated Rose followed her down the hall.

In the salon she told her husband, “Closed the window over the cheeseâa full kilogram of cheese suffocating all night with the window closed. And do you know what her excuse was? She was cold. For her own comfort the cheese must strangle. You can't trust servants anymore.”

Monsieur said, “One finds oneself in a difficult situation.”

“Difficultâof course it's difficult with the kind of trash who call themselves cooksâ”

“Madameâthe meteor shower continues. This is verified. I find I must procure a new camera.”

The outgo of money was definitely in Madame's province. She remained silent, but Monsieur sensed danger in her narrowing eyes and in her hands, which rose slowly and saddled her hips.

He said uneasily, “It is a decision one must make. No one is to blame. One might say the order comes from Heaven itself.”

Madame's voice was steel. “The cost of thisâthis camera, Monsieur?”

He named a price which shook her sturdy frame as though an internal explosion had occurred. But almost immediately she marshaled herself with iron discipline for the attack.

“Last month, M'sieur, it was a newâwhat do you call it? The expenditure for film is already ruinous. May I remind you, M'sieur, of the letter recently arrived from Auxerre, of the need for new cooperage, of the insistence that we stand half of the cost?”

Other books

Slocum 394 : Slocum and the Fool's Errand (9781101545980) by Logan, Jake

Trouble in the Pipeline by Franklin W. Dixon

Barbara Silkstone - Wendy Darlin 04 - Miami Mummies by Barbara Silkstone

Noah Barleywater Runs Away by John Boyne

Dragonlance 16 - Dragons Of A Lost Star by Weis, Margaret

Confession by Gary Whitmore

Supernatural: Bobby Singer's Guide to Hunting by David Reed

One Mistake (The One Series: Novella #2) by King, Emma J.

Violence by Timothy McDougall

ClaimedbytheNative by Rea Thomas