The Silk Road: A New History (24 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

The excavations at Panjikent have so far uncovered about 15–17 acres (6–7 hectares), or one-half of the small city. Built sometime in the fifth century, the city reached its largest size in the seventh century. Panjikent fell to Arab armies in 722, revived briefly in the 740s, and then was completely abandoned between 770 and 780.

29

Between five and seven thousand inhabitants lived there, surrounded by a city wall dating to the fifth century. Their city contained several streets, alleyways, two bazaars, and two temples, one with a side fire altar, the other with images of at least ten different deities.

30

This temple had a room with a separate entrance that housed a statue of the Indian god Shiva sitting on a bull holding a trident. His trident and erect penis conformed to Indian prototypes, but his boots were Sogdian.

Commercial granaries and bazaars show that a retail trade existed in Panjikent. Although archeologists have not found evidence of permanent buildings to house caravans, called caravanserai in Persian, anywhere in Sogdiana, some modern historians believe that the caravanserai originated in the region. The geographer Ibn H. awqal described the ruin of a giant building that could house up to two hundred travelers and their animals, with food for all and room to sleep as well.

31

Several Panjikent houses had courtyards large enough to house a caravan, and the word “hotel” in Sogdian (

tym

) was borrowed from the Chinese word “inn” (

dian

).

32

Caravans passed through Panjikent, since it was on the road between Samarkand and China, which crossed the Ammoniac Mountains, a major source of ammonium chloride in the Tianshan Mountains between modern-day Tajikistan and China.

33

Yet few artifacts found in Panjikent can be identified as coming via the caravan trade; small glass vessels dating to the seventh century are one important exception. Local production of glass began only in the mid-eighth century.

34

More evidence of trade lies in the thousands of bronze coins found in the city, many apparently loose change discarded or mislaid at the market place. Silver coins, from the Sasanian Empire, also circulated during the sixth century in smaller quantities. The earliest locally minted coins date to the second half of the seventh century. Apparently the central authorities granted local workshops the right to make coins. In the seventh century, the period of greatest contact between Sogdiana and China, the residents of Panjikent used bronze coins with the same shape as Chinese coins—round coins with a square hole—some with Chinese characters on them, some without.

As at Turfan, residents sometimes used gold coins. Between 1947 and 1995, archeologists found two genuine gold coins from the Byzantine Empire and six extremely thin imitations. Five, found in houses, indicate that the coins and the imitations were used as currency.

35

Similarly, imitation gold coins also served as burial goods. Two of the gold coins (and possibly a third) were found inside

naus

structures the Sogdians built to house the dead, usually members of the same family. These buildings were small, square, and made of mud brick; they held the cleaned bones in ossuaries.

36

Zoroastrian texts do not mention naus buildings, which first appear in the Samarkand region—but not in central Iran—in the late fourth or fifth centuries.

Motifs on some of the ossuaries document the belief that Ahura Mazda would use the bones of the deceased to reconstitute them on the Judgment Day.

37

The burial of coins with the dead shows that the living thought they would benefit from having a gold coin, or an imitation gold coin, near them. The practice does not seem to have been limited to the wealthy; one of the deceased buried with such coin was a potter.

38

Not all the dead were buried in Zoroastrian ossuaries; one graveyard in Panjikent included tombs with fully extended bodies, apparently Christian-style burials. One corpse wore a cross made from bronze.

39

A writing exercise in Syriac has been found, most likely copied by a Sogdian student studying the liturgical language of the Church of the East.

40

ZOROASTRIAN BURIAL IN SAMARKAND

This clay ossuary, found in the village of Molla-Kurgan outside Samarkand, held the bones of the deceased after they had been cleaned. The lid of the box shows two woman dancers wearing transparent robes. Since there is no evidence of priestesses in the Samarkand region, they may be mourners at a funeral, or perhaps beautiful young women coming to greet the newly dead in the afterlife. The base shows a fire altar flanked by two Zoroastrian priests, who wear padam face masks and head coverings to keep any bodily substance or hair from polluting the fire. Courtesy of Frantz Grenet.

The houses excavated so far, numbering over 130, include the dwellings of ordinary people as well as the very rich.

41

The large houses all have a fire altar in one room, the room for family prayers. Smaller, portable fire altars were kept in reception halls; these held religious images as well as pictures of worshippers, themselves often family members. The widespread presence of fire altars throughout the city indicates that most of the town’s residents were Zoroastrians, but the Sogdians were open to other religious beliefs as well.

Different Sogdian households chose a deity that they worshipped in their own houses and whose pictures they placed on the walls of their reception rooms. These deities, with varying iconographical attributes, have not all been identified. Clearly Nana, an originally Mesopotamian goddess, had many devotees.

42

A deity shown sitting on a camel or holding a small camel figurine was also venerated by travelers.

43

One house owner placed a small image of the Buddha in a separate room in his house; although not as big as the paintings of the God of Victory and Nana in his house, the image demonstrates his willingness to accept a non-Sogdian deity.

44

PANJIKENT STREET SCENE

The wealthiest urban residents lived in multistoried dwellings with large halls, which could seat a hundred, complete with elaborate wall paintings and lavish carvings (4). Their homes were located close to shops and craftspeople’s workshops (7) and a forge (8). Their poorer neighbors lived in smaller houses, often of two stories and sometimes with several rooms decorated with small paintings (9). Their occupants produced the crafts and staffed the shops where the rich purchased these items. From Guitty Azarpay,

Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art,

University of California Press, 1981 © The Regents of the University of California.

The houses of the wealthiest have wall paintings extending from the ceiling to the floor divided into different levels. On the highest part of the wall, facing doorways, are large portraits of deities, with donors—the householders themselves—below. The middle section paintings, roughly one yard (1 m) high, portray well-known folk tales from other countries: the Iranian epic Rustam, Aesop’s fables, and Indian tales from the Panchatantra. In the bottom frame, usually about 20 inches (.5 m) high, are scrolls showing scenes in sequence that would have been narrated by a storyteller. As the page-sized format makes clear, these were copied from book illustrations.

45

Although the residents of Panjikent commissioned paintings with many different types of subject matter, almost no paintings show commercial activity. Archeologists have identified one house with a painting of a lavish banquet as the house of a merchant who lived immediately next to one of the bazaars. The sole indication that the guests are merchants—and not nobles—is that, instead of the usual sword, one guest wears a black bag attached to his belt.

46

Merchants are also absent from the large and beautiful set of murals from the Afrasiab site in Samarkand, which provide a visual introduction to the political situation of Samarkand. The realistic subject matter of the Afrasiab paintings distinguishes them from other Sogdian wall paintings depicting legends and deities found at Panjikent and the Varakhsha fortress outside Bukhara. They were painted between 660 and 661 during the reign of the Sogdian king Varkhuman, a name that appears in the official Chinese histories, because the Chinese emperor Gaozong (reigned 649–83) awarded him the title of governor of Sogdiana. In 631, an earlier Sogdian king made a similar request for an alliance with the Chinese, but the emperor Taizong turned him down on the grounds that Samarkand was too distant and that the Chinese would be unable to send troops if they were needed.

47

Now located in the Afrasiab History Museum, these paintings were salvaged in 1965 after a bulldozer digging a new road removed the room’s ceiling. The Afrasiab wall paintings stand over 6.5 feet (2 meters) tall and 35 feet (10.7 m) long and fill the four walls of an imposing square room in the house of a wealthy, aristocratic family. As the top section of the paintings on three of the four walls was bulldozed away, archeologists are uncertain of the paintings’ original height.

48

The Afrasiab paintings deserve careful study because they illuminate how the Sogdians viewed the larger world.

49

A few different figures, including a goose and a woman, bear labels written in small black Sogdian script that identify their owner as Varkhuman, who was probably acquainted with the owners of the house. One enters the room with the paintings through the heavily damaged eastern wall, which shows scenes from India, but it is difficult to make much out.

50

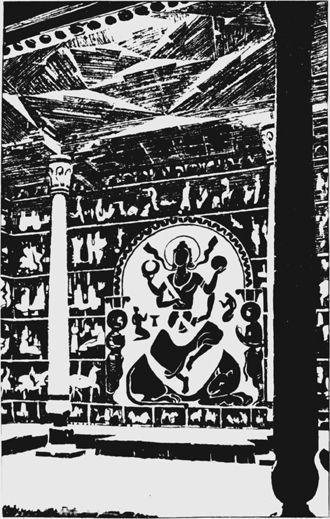

PANJIKENT HOUSE

Many of the houses of the wealthy in Panjikent had a large reception room like this with high columns that displayed a painting of a deity. This family worshipped the originally Mesopotamian deity Nana, but other Panjikent houses had paintings of other deities as well. Note the multiple tiers of painting on the wall behind the goddess; Panjikent artists typically divided wall paintings into horizontal sections like this. From Guitty Azarpay,

Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art,

University of California Press, 1981 © The Regents of the University of California.

The western wall facing the viewer portrays ambassadors and emissaries from different countries, who march in an impressive procession. Bulldozed away, the top figure presiding over the scene is missing. On the left-hand side of the western wall, a headless figure, the second from the left, is wearing a white robe with a long inscription in Sogdian on it. This inscription, the only long text on the painting, records the speech of an envoy from Chaghanian, a small kingdom just south of Samarkand near the modern city of Denau, Uzbekistan, as he presents his credentials to Varkhuman: